Introduction

In ESRD patients on renal replacement therapy, K homeostasis is mainly maintained on adequate dialytic K removal and adapted extrarenal K regulation1). However, due to the different dialysis modes between HD and CAPD, i.e. the episodic (3-4 times/wk) in HD versus the daily continuous dialysis in CAPD, HD patients do not achieve a steady blood [K] leading to usually highest before dialysis and lowest immediately after dialysis while CAPD patients approach a steady state for it's level, so that wide variations in blood [K] are not present. Excessive dietary K gain before dialysis in HD can temporarily contribute to the development of hyperkalemia but poor dietary K intake in CAPD may lead to hypokalemia. Therefore, hyperkalemia would be more frequent in hemodialysis than in CAPD, especially predialysis stage, and hypokalemia more frequent in CAPD than in HD.

The K imbalance in dialysis patients seems to be primarily related to poor dietary compliance. In fact, too much K intake with poor compliance to diet in interdialytic interval in HD despite adequacy of HD contributes to the high frequency of hyperkalemia (10-24%) responsible for the most common cause of death (3-5%) among electrolyte imbalances, whereas malnutrition with poor K intake in CAPD is a well known factor for the high prevalence of hypokalemia (10-36%) leading to the higher cardiovascular mortality than normokalemic CAPD patients in a recent study2).

However, besides dietary factors, there are other important factors to be considered among the causes of K imbalance in dialysis patients regardless of dialysis modes, since they are mostly remediable with identifying and then avoiding or removing them. Those are clinical conditions causing the derangement of the external K regulation including abnormal colonic K secretion, i.e. constipation or diarrhea, as well as administration of drugs affecting internal K balance in K homeostatic mechanism related to neurohormones such as insulin, catecholamines, and renin-angiostensin-aldosterone (RAS), such as non-selective bet-ablockers, ACE-inhibitors and/or ARBs, and aldosterone receptor blocker (spironolactone, eplerenone). As an another factor for K homeostasis in the patients on CAPD, daily continuous infusion of standard glucose containing dialysates might be involved in intracellular K shift related to insulin hormone and showed high intracellular K contents in muscles as shown in a few studies. Recently, Icodextrin with glucose-polymer solution leading to less glucose load and less insulin secretion has been replaced for the patients on CAPD with ultrafiltration failure during long-overnight dwell, which might affect K distribution in them3).

In this paper, the etiologies responsible for hyperkalemia in HD and for hypokalemia in CAPD with evaluation of their prevalence and incidence as well as their treatments based on the contributing factors for the K imbalances are reviewed with collected data from the literature and our data.

Go to :

Hyperkalemia on Hemodialysis

HD patients with ESRD are continuously exposed to the risk of hyperkalemia due to episodic removal of body K through dialysis for 3 to 4 hrs with 3 or 4 times per week in frequency rather than continuous K excretion by the intact kidneys. However, the degree of hyperkalemia in HD during the interdialytic perod depends on several factors : 1) a dietary K intake, 2) the amount of dialysate K removal by HD related to the [K] gradient and to the K passive refilling fro ICF to ECF, 3) increased intestinal excretion of K as an adaptive extrarenal K homeostasis4), and 4) the transcellular K shifts as in healthy subjects.

Hyperkalemia was pointed out as a "potential silent killer" and suggested even one of the leading causes of sudden death in HD patients5). In our survey of HD patients during past 10 yrs, 108 out of 548 patients (20%) expired, and its most common causes are cardiovascular disorder (44%) and infection (17%) same as reported in the world literature, but other notable causes included unknown etiologies (22%) and hyperkalemia (6%)6). In the admitted patients with severe hyperkalemia, the most common causes of hyperkalemia were related to inadequate dialysis with noncompliance to HD frequency per week (55%) and excessive K intake with noncompliance to dietary regimen (35%) followed by others including medications7).

Nonselective beta-blockers have been shown to increase serum [K] in patients with ESRD due to preventing intracellular K shift by the inhibition of beta-2 adrenergic receptors.8-9 However, nonselective beta-adrenergic blocker with a selective alpha-1 blocking activity, carvediolol, did not enhance the hyperkalemic effect of moderate physical exercise on HD, but in our observation predialysis-serum [K] with carvediolol was significantly higher than that without it (5.13±1.0 mEq/L vs 5.7±1.0 mEq/L)10).

Though renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers such as ACEi, ARB and spironolactone or Eplerenone currently are recommended in HD patients for the cardio-protective effects, it has been reported to be independently associated with an increased risk of developing hyperkalemia11). Recently, low-dose spironolactone, 25 mg/d12), and even the combined therapy of RAS blockers with ACE plus ARB failed to show any significant increase in frequency of hyperkalemia and in the higher mean serum K level when compared to basal values without their exposure in our study (no-exposure, 5.54±0.67 mEq/L; ACEi alone, 5.54±0.75 mEq/L; ARB alone, 5.50±0.66 mEq/L; ACEi plus ARB, 5.42±0.66 mEq/L, p=NS)13). These contradictory data suggest that the cautious trial of RAS blockers, either alone or combined, would be justified with the overweighing benefits of the cardioprotective effects for the patients on HD rather than their hyperkalemic risks.

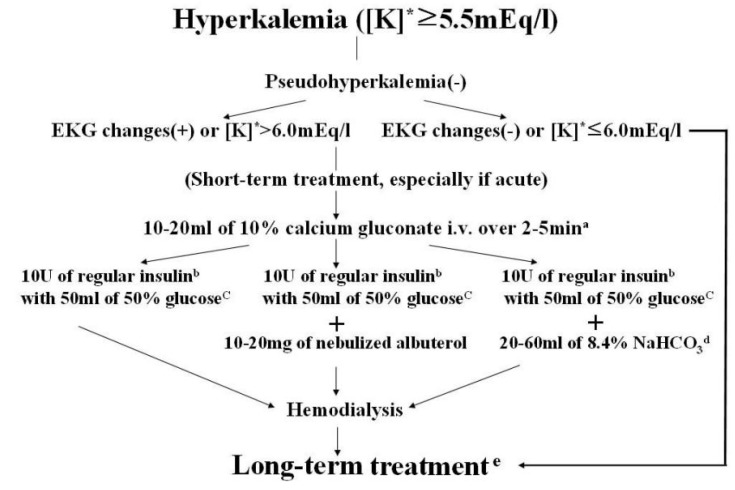

Before the initiation of HD as the most efficient treatment of hyperkalemia is available, other conservative managements of the emergency treatment of hyperkalemia consists of four basic modalities as monotherapy including calcium gluconate, insulin with glucose, nebulized beta-2 agonists, intravenous NaHCO3 and oral or rectal cation-resins. However, the effect of NaHCO3 for the treatment of hyperkalemia is uncertain and its infusion in varying amount failed to lower serum [K] in ESRD patients14), but when combined with insulin with glucose or beta-2 agonists (NAHCO3 alone, -0.13±0.06, p=NS; Salbutamol alone, -0.57±0.03 mEq/L, p<0.02; NaHCO3 plus salbutamol, -0.96±0.08 mEq/L, p=0.000), their hypokalemic effect were enhanced probably due to the activation of Na-K pump with acute correction of underlying metabolic acidosis in the combined regimen with bicarbonate as dual therapy15, 16). Also, other study introduced the efficacious and safe modalities for the acute treatment of hyperkalemia in ESRD patients with the combined regimens as dual therapy, insulin with glucose plus beta 2-agonists17).

Therefore, once pseudohyperkalemia also present in HD patients as in other general patients is excluded18), the temporizing measures of transcellular K shifting regimens can be initiated alone or combined therapy to buy time until hemodialysis can be initiated with the assessment of EKG at the outset as shown in the flow chart (Fig. 1)19). As a long-term treatment plan of hyperkalemia in HD, the correction of the underlying pathophysiology responsible for hyperkalemia should be started with removal or cautious trials of medications inducing hyperkalemia with balancing the ratio of their benefits and risks in addition to improving the compliance to dialysis and diet. Among other therapeutic regimen for hyperkalemia on the long-term basis, the administration of laxative such as bisacodyl increasing colonic K seretion20), and exogenous mineralocorticoid or mineralocorticoid-like substance may provide simple means of reducing interdialytic hyperkalemia in HD21, 22).

| Fig. 1Flow chart for treatment of hyperkalemia. [K]* : serum potassium concentration. a : Can be repeated until resolving EKG changes. b : Intravenous bolus injection. c : If blood glucose is more than 250 mg/dL, can be omitted. d : Not proven unanimously. e : See this paper for instructions (Kim HJ, Han SW. Therapeutic approach to hyperkalemia, Nephron 92(suppl 1):33-40, 2002). |

Go to :

Hypokalemia on CAPD

In our analysis of serum [K] profile in stable CAPD patients (n=253)23), normokalemia (83%) and hypokalemia (16%) were much more frequent than hyperkalemia (1%), being similar to the recent data of Chinese CAPD patients, i.e. normokalemia (80%), hypokalemia (20%), and none in hyperkalemia2). The Chinese data revealed that serum [K] is correlated with serum albumin level (r=0.17; p=0.005) suggesting close relation between hypokalemia and malnutrition. Also, on analysis of serum [K] profile in admitted CAPD patients for 3 yrs, we observed the significant differences between groups of hypokalemia (11/48, 23%) and without hypokalemia (37/48, 77%) in serum albumin, BUN, and creatinine levels. Furthermore, the history of poor dietary intake was more prominent in hypokalemic patients (9/11 vs 6/37, p<0.01), but daily K loss via dialysates was similar in two groups. These data support strongly that high prevalence of hypokalemia in CAPD as well as the close correlation of hypokalemia with malnutrition and poor dietary K intake24). However, one study investigated for the pathogenetic mechanism of hypokalemia in CAPD with measuring the amount of K intake minus that of urinary and peritoneal K excretion and considering stool K losses of around 6-50 mEq/day. External K imbalance (i.e. K losses) alone was not enough to justify the hypokalemia. Therefore, the deranged internal K balance, i.e. intracellular K shift by mostly insulin hormone stimulated by the continuous glucose peritoneal infusion in CAPD, was proposed as a contributory factor for the development of hypokalemia even in the context of a low K excretion25). In our recent study, the mean serum [K] was higher in the group of glucose-free dialysates (Icodextrin) than in the group of standard glucose dialysates for long overnight-dwell (4.6±0.1 mEq/L vs 4.4±0.1 mEq/L, p<0.05).13 For K supplementation in the management of hypokalemia, K could be generally administered via oral or intravenous routes. Furthermore, K mixed with dialysate solution would be administered thru intraperitoneal route upto 40 mEq in 2 L dialysate safely. In hypokalemic patient (<3.5 mEq/L), 40 mEq KCl in 2 L dialysate was administered safely and efficiently. The degree of K absorption via peritoneum and that of intracellular shift of absorbed K were 76±6% and 74±19%, respectively, and the increment of serum [K] was 0.8±0.2 mEq/L.26 A recent study of comparison of intraperitoneal K administration (40 mEq mixed in 2 L dialysate) after one exchange between standard 2.5% glucose and glucocose-free (Icodextrin) dialysates revealed the less increase in serum [K] (0.18±0.1 mEq/L vs 0.56±0.1 mEq/L, p<0.05), despite the less increment of insulin level from basal value (-19±9% vs 37±12%) in the latter and similar blood glucose concentrations in two different dialysates13).

Undoubtedly, acute administration of K in hypokalemic patients in CAPD regardless its routes would be necessary for its correction to avoid neuromuscular weakness and serious cardic arrhythmia. Nevertheless, in the chronic long-term basis, further investigation may be required to investigate the benefits of K supplementation alone, because hypokalemia may simply be surrogate marker of malnutrition and/or other serious comorbid illness.

Go to :

Conclusion

In dialysis patients, i.e. HD or CAPD, K imbalance should be always considered as a common condition related to either a potentially lethal condition itself or the important contributory factor for their morbidity and mortality. The pathophysiologic factors for hyperkalemia in HD are well understood, and accordingly its managements are somewhat straightforward, while the pathogenetic mechanisms of hypokalemia in CAPD need further clarification for the role of intracellular K redistribution.

For the management of K imbalance in dialysis, the foremost step is to improve compliance to dietary K intake and dialysis regimen besides the reversal or removal of pathophysiologic factors and other potential sources including drugs affecting K imbalance should be always considered. However, cautious administration of certain beneficial drugs such as RAAS blockers could be justified in ESRD on dialysis with tremendous burden with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. As temporizing acute K-lowering regimens in severe lifethreatening hyperkalemia, dual-therapeutic regimens, i.e. NaHCO3 plus insulin with glucose or insulin with glucose plus beta-2 agonist, could be recommended as an efficacious modality. In CAPD patients with hypokalemia, for the long-term management, the correction of malnutrition would be required as one of the essential managements and the selection of glucose-free dialysates such as Icodextrin could be considered rather than the conventional glucose dialysates. Also, as short-term management, K supplements could be administered safely and efficiently via intraperitoneal route, if required.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download