Abstract

A clear appreciation of benefits and risks associated with living donor hepatectomy is important to facilitate counselling for the donor, family, and recipient in preparation for living donor liver transplant (LDLT). We report a life-threatening complication occurring in one of our live liver donors at 12 weeks following hemi-liver donation. We experienced five donor complications among our first 50 LDLT: Clavien Grade 1, n=1; Clavien grade 2, n=3; and Clavien grade 3B, n=1. The one with Clavien grade 3B had a life-threatening diaphragmatic hernia occurring 12 weeks following hepatectomy. This was promptly recognized and emergency surgery was performed. The donor is well at 1-year follow-up. Here we provide a review of reported instances of diaphragmatic hernia following donor hepatectomy with an attempt to elucidate the pathophysiology behind such occurrence. Life-threatening donor risk needs to be balanced with recipient benefit and risk on a tripartite basis during the counselling process for LDLT. With increasing use of LDLT, we need to be aware of such life-threatening complication. Preventive measures in this regard and counselling for such complication should be incorporated into routine work-up for potential live liver donor.

Living donor liver transplant (LDLT) is seen as a panacea for severe shortage of deceased donor liver grafts. Indeed, most programs in the eastern world have relied on living liver donors to save lives of a vast number of patients with decompensated liver diseases. Substantial risks associated with live donor liver hepatectomy are also increasingly recognized. Increasing use of this treatment modality will no doubt enhance the occurrence of serious complications in healthy persons who volunteer as living liver donors of hemi-livers.

Recent reports from A2ALL studies1 in US centers and a further world-wide survey2 have gathered data on donor mortality, morbidity, and near-miss events from across the US and the rest of the world. It is well accepted that near-miss events portend the occurrence of a serious event like mortality in the context of surgical risk assessment. Recognition of these near-misses will help us modify practice and prevent occurrence of future catastrophic event.

We describe a life-threatening complication in one of our living hemi-liver donors which needed emergency surgery. This event was certainly a near-miss of donor mortality. Although this near-miss appears to be a random event, review of literature suggests otherwise. There have been at least 10 reports of diaphragmatic hernia (DH) following live liver donor hepatectomy. This prompted us to review possible factors responsible for this complication and explore means to prevent this from happening again.

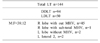

A young engineer who had volunteered as a living liver donor for his grandfather underwent a middle hepatic vein (MHV)-preserving right lobe hepatectomy in a standard uneventful manner. He was discharged on day 10. His hemi-liver recipient who recovered in a pretty straightforward fashion was discharged home on day 19. Follow-ups for both patients were unremarkable. The recipient continued to do well. The donor went back to his place of usual residence about 120 km away from the Transplant Center. However, at 12 weeks following the hepatectomy, the donor developed sudden severe unrelenting abdominal pain. This did not settle, thus he sought medical advice at a local hospital. The physician who assessed him found him diaphoretic. He was in great pain with a tachycardia of about 120/min, although he had normal blood pressure. Abdominal examination revealed some tenderness but no guarding. No specific chest auscultation findings were recorded. He was referred to a secondary care hospital for further management. After initial resuscitation, a surgical assessment was made. After consultation with the transplantation team, computed tomography (CT) scan was performed. Coronal/oblique reformatted images from this study are depicted in the composite panel as shown in Fig. 1.

These video images were sent to us by “WhatsApp”. Upon review of the clinical situation and images, it was clear that our patient needed an emergency operation. He was transported (120 km distance) to our Unit by ambulance where he underwent an emergency laparotomy. The distal small bowel and right colon had herniated into the chest through a small defect in the right hemi-diaphragm. The gut was reduced into the abdomen and resected. Primary end-to-end anastomosis was carried out as it was found to be non-viable. Residual small bowel measured 220 cm. The defect in the diaphragm was closed primarily with non-absorbable Prolene 1-0 sutures. Our patient made an uneventful recovery. He was discharged 10 days after the surgery. He continues to do well at 1-year follow up. He is back to all pre-donation activities, including full-time work as a civil engineer.

Living donors are increasing sources of liver grafts ever since the first described pediatric LDLT. The procedure has been successfully adapted to adult situation. It has been expanded to dual-lobe grafts and ABO-incompatible transplantation. Recommendation of a LDLT takes recipient risk, benefit, and alternative treatment option (i.e., medical management of decompensated liver disease) into account. Compared to deceased donor liver transplantation, LDLT introduces donor risk as a unique variable into the decision-making process. Therefore, a tripartite equipoise has been described for LDLT situation.34 To have informative discussion and subsequent decision, reliable data on donor risk are required. However, such data are lacking, although it has been 20 years since the first description of this technique. It is well accepted that surgical complications are significantly under-reported.5 This is particularly true for living donor related morbidity and mortality.6

A review of all published articles from medical literature on LDLT and search of lay literature for donor deaths from 1989 to February 2006 revealed 19 donor deaths and one additional donor in a chronic vegetative state. Thirteen deaths and the vegetative donor were “definitely” related to donor surgery. Two were “possibly” related while four were “unlikely” to be related to donor surgery.7 The A2ALL consortium has reported that 40% of donors have complications (557 complications among 296 donors out of a total of 740 living donors. Most of those complications are Clavien grades 1 and 2: grade 1 (minor, n=232); grade 2 (possibly life-threatening, n=269); grade 3 (residual disability, n=5), and grade 4 (leading to death, n=3).1 However, the exact number of donor deaths across the world, especially those in India, are not documented. Until mid-2013, apparently seven donor deaths had occurred in India.8 A further death was reported later that year.9

According to a worldwide survey, the average donor morbidity rate is 24%, with 5 donors (0.04%) requiring transplantation.2 Donor mortality rate is 0.2% (23/11,553), with majority of deaths occurring within 60 days after donation surgery. All but four deaths were related to the donation surgery. Incidences of near-miss for donor death events and aborted hepatectomies were reported to be 1.1% and 1.2%, respectively.2 This report emphasized the significance of near-miss events, including hemorrhaging requiring surgical intervention, thrombotic events, biliary reconstruction procedures, life-threatening sepsis, and iatrogenic injury to the bowel or vasculature. Amongst these near-miss events, two reoperations for diaphragmatic hernia were reported from two centers. In addition, there were two cases of gastric volvulus. What is important is that nearly half of these near-miss events are not directly related to the liver. These near-miss events could have easily resulted in donor mortality, given the extremely serious nature of these complications.

In our patient, prompt recognition and expeditious management of the serious complication resulted in a positive outcome for the liver donor. However, numerous lessons can be learnt from the occurrence of this complication.

Importantly, the occurrence of diaphragmatic hernia following a living donor hepatectomy is not rare. A search of major databases revealed a total of 10 cases of DH after LDLT, including one patient reported from USA in 2006,10 two patients reported from USA in 2011,1112 one reported from Essen, Germany,13 one reported from India,14 one reported from Taiwan in 2015,15 and three patients reported from Hanover, Germany in 2011.16 DH has also been reported after left liver donation, which may be a left-sided DH.

Ten DH cases in recipients following pediatric LT from a single institute were reported in 2014. The following risk factors for DH were identified: early age, split graft, and high graft to recipient weight ratio (GRWR). A further review of three cases from Japan suggests that DH following LT should be considered as a potential surgical complication when a left-sided graft is used, especially in small infant recipients with coagulopathy and malnutrition.17 Factors responsible for diaphragmatic hernia following liver transplantation in pediatric population include the following: diaphragm thinness related to low weight and malnutrition; direct trauma at operation (dissection and diathermy); increased abdominal pressure after transplantation caused by the use of a slightly oversized liver graft; and medial positioning of the partial liver graft in the abdomen.

DH has also been reported after open liver resections.18 There is also a single case report of a laparoscopic liver resection resulting in DH.19 A microwave coagulator was used during this laparoscopic operation. Most DH cases following liver resections (both for living liver donation or otherwise) occurred many months following the initial operation except the report from Taiwan and the current patient. Reasons for the development of this complication could be due to a combination of factors, including the following: a thin diaphragm in young donors combined with the use of diathermy during mobilization of the right lobe resulting in unnoticed thermal muscle damage which manifests at a later time; and loss of volume in the right hypochondrium with resultant migration of the gut to occupy the space and subsequent increased abdominal pressure resulting in herniation through a weakened area of the diaphragm muscle. Of course, iatrogenic gross injury to the diaphragm muscle could occur and a repair of this damage could later fail with resultant herniation of gut into the chest. This has not been described in any report yet. It was not the case in our patient.

Understanding of the pathophysiology of the development of DH is crucial to its prevention. We advocate the use of monopolar diathermy forceps in a “forced setting” to mobilize the right lobe in the correct loose areolar tissue plane rather than using a “pencil diathermy instrument” in spray coagulation mode, although spray coagulation is extremely useful as a hemostatic tool that can result in significant heat dispersal into surrounding tissues.20 In addition, avoidance of mobilization of the hepatic flexure, right colon, and small bowel mesentery will help minimize gut migration. We would also advocate careful visual inspection of the right hemi-diaphragm at the end of the operation to identify and repair any inadvertent damage to the muscle. This is now a routine practice in our Unit in an effort to improve donor safety. Counselling for this particular complication is also part of the routine work-up and informed consent for a potential live liver donor.

In conclusion, recognition of the relative frequent occurrence of this particular problem as a specific potential complication of a living donor hepatectomy should be included in the counselling process for the living donor. Surgical technique should also be modified considering such complication. Careful watch for the occurrence of a DH should be mandatory during follow-up.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Abecassis MM, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, Freise CE, Rodrigo DR, Samstein B, et al. Complications of living donor hepatic lobectomy--a comprehensive report. Am J Transplant. 2012; 12:1208–1217.

2. Cheah YL, Simpson MA, Pomposelli JJ, Pomfret EA. Incidence of death and potentially life-threatening near-miss events in living donor hepatic lobectomy: a world-wide survey. Liver Transpl. 2013; 19:499–506.

3. Roll GR, Parekh JR, Parker WF, Siegler M, Pomfret EA, Ascher NL, et al. Left hepatectomy versus right hepatectomy for living donor liver transplantation: shifting the risk from the donor to the recipient. Liver Transpl. 2013; 19:472–481.

4. Miller C, Smith ML, Fujiki M, Uso TD, Quintini C. Preparing for the inevitable: the death of a living liver donor. Liver Transpl. 2013; 19:656–660.

5. Hutter MM, Rowell KS, Devaney LA, Sokal SM, Warshaw AL, Abbott WM, et al. Identification of surgical complications and deaths: an assessment of the traditional surgical morbidity and mortality conference compared with the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2006; 203:618–624.

6. Karen Dent. Donor risk remains a challenge in liver transplantation. Paper presented at: International Liver Transplantation Society 13th Annual International Congress. Jun 21, 2007.

7. Trotter JF, Adam R, Lo CM, Kenison J. Documented deaths of hepatic lobe donors for living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006; 12:1485–1488.

8. Gupta S. Living donor liver transplant is a transparent activity in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013; 3:61–65.

9. Reddy MS, Narasimhan G, Cherian PT, Rela M. Death of a living liver donor: opening Pandora's box. Liver Transpl. 2013; 19:1279–1284.

10. Hawxby AM, Mason DP, Klein AS. Diaphragmatic hernia after right donor and hepatectomy: a rare donor complication of partial hepatectomy for transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2006; 5:459–461.

11. Dieter RA Jr. Postoperative right diaphragmatic hernia with enterothorax in live liver donors. Exp Clin Transplant. 2011; 9:353.

12. Dieter RA Jr, Spitz J, Kuzycz G. Incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia with intrathoracic bowel obstruction after right liver donation. Int Surg. 2011; 96:239–244.

13. Vernadakis S, Paul A, Kykalos S, Fouzas I, Kaiser GM, Sotiropoulos GC. Incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia after right hepatectomy for living donor liver transplantation: case report of an extremely rare late donor complication. Transplant Proc. 2012; 44:2770–2772.

14. Perwaiz A, Mehta N, Mohanka R, Kumaran V, Nundy S, Soin AS. Right-sided diaphragmatic hernia in an adult after living donor liver transplant: a rare cause of post-transplant recurrent abdominal pain. Hernia. 2010; 14:547–549.

15. Jeng KS, Huang CC, Lin CK, Lin CC, Wu JM, Chen KH, et al. Early incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia following right donor hepatectomy: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2015; 47:815–816.

16. Kousoulas L, Becker T, Richter N, Emmanouilidis N, Schrem H, Barg-Hock H, et al. Living donor liver transplantation: effect of the type of liver graft donation on donor mortality and morbidity. Transpl Int. 2011; 24:251–258.

17. Shigeta T, Sakamoto S, Kanazawa H, Fukuda A, Kakiuchi T, Karaki C, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia in infants following living donor liver transplantation: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Transplant. 2012; 16:496–500.

18. Tabrizian P, Jibara G, Shrager B, Elsabbagh AM, Roayaie S, Schwartz ME. Diaphragmatic hernia after hepatic resection: case series at a single Western institution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012; 16:1910–1914.

19. Sugita M, Nagahori K, Kudo T, Yamanaka K, Obi Y, Shizawa R, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia resulting from injury during microwave-assisted laparoscopic hepatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003; 17:1849–1850.

20. Vilos GA, Rajakumar C. Electrosurgical generators and monopolar and bipolar electrosurgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013; 20:279–287.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download