Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify effects of fatigue, depression and anxiety on quality of life in pregnant women with preterm labor.

Methods

With a survey design, data were collected from 138 mothers who were admitted at a hospital in Seoul, between June 2014 and September 2015. Instruments used to collect the data for the study were: Fatigue Continuum Form, Depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) and maternal postpartum quality of life (MAPP-QOL).

Results

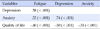

The mean fatigue score was 68.30 with 50.7% of women being depressed and 79.7% of the 138 women being anxious. The mean quality of life was 18.92 with quality of life being associated with fatigue, depression and anxiety. Depression and fatigue explained 26% of the variance in quality of life.

Figures and Tables

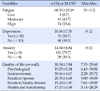

Table 1

Demographic and Obstetric Characteristics in Subjects (N=138)

Table 2

Levels of Fatigue, Depression, Anxiety and Quality of Life (N=138)

Table 3

Comparison of Quality of Life according to Subjects Characteristics (N=138)

References

1. Choi SY, Gu HJ, Ryu EJ. Effects of fatigue and postpartum depression on maternal perceived quality of life (MAPP-QOL) in early postpartum mothers. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2011; 17(2):118–125.

2. Wang P, Liou SR, Cheng CY. Prediction of maternal quality of life on preterm birth and low birthweight: A longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013; 13:124.

3. Lau Y, Yin L. Maternal, obstetric variables, perceived stress and health-related quality of life among pregnant women in Macao, China. Midwifery. 2011; 27(5):668–673.

4. Roy-Matton N, Moutquin JM, Brown C, Carrier N, Bell L. The impact of perceived maternal stress and other psychosocial risk factors on pregnancy complications. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011; 33(4):344–352.

5. Calou CGP, Pinheiro AKB, Castro RCMB, de Oliveira MF, de Souza Aquino P, Antezana FJ. Health related quality of life of pregnant women and associated factors: An integrative review. Health. 2014; 6(18):2375–2387.

6. Gartland D, Brown S, Donath S, Perlen S. Women's health in early pregnancy: Findings from an Australian nulliparous cohort study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010; 50(5):413–418.

7. Beck S, Wojdyla D, Say L, Betran AP, Merialdi M, Requejo JH, et al. The worldwide incidence of preterm birth: A systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity. Bull World Health Organ. 2010; 88:31–38.

8. Statistics Korea. Infant mortality rate [Internet]. Seoul: Author;2012. cited 2016 May 30. Available from: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/3/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=269012.

9. Stinson JC, Lee KA. Premature labor and birth: Influence of rank and perception of fatigue in active duty military women. Mil Med. 2003; 168(5):385–390.

10. Kajeepeta S, Sanchez SE, Gelaye B, Qiu C, Barrios YV, Enquobahrie DA, et al. Sleep duration, vital exhaustion, and odds of spontaneous preterm birth: A case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014; 14:337.

11. Go JI, Kim KH, Yeoum SG. Relationship with physical suffering, emotional state, and nursing needs of pregnant women in preterm labor. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2009; 15(4):280–293.

12. Nicholson WK, Setse R, Hill-Briggs F, Cooper LA, Strobino D, Powe NR. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 107(4):798–806.

13. Da Costa D, Dritsa M, Verreault N, Balaa C, Kudzman J, Khalife S. Sleep problems and depressed mood negatively impact health-related quality of life during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010; 13(3):249–257.

14. Setse R, Grogan R, Pham L, Cooper LA, Strobino D, Powe NR, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life during pregnancy and after delivery: The health status in pregnancy (HIP) study. Matern Child Health J. 2009; 13(5):577–587.

15. Kramer MS, Lydon J, Seguin L, Goulet L, Kahn SR, McNamara H, et al. Stress pathways to spontaneous preterm birth: The role of stressors, psychological distress, and stress hormones. Am J Epidemiol. 2009; 169(11):1319–1326.

17. Song JE. A comparative study on the level of postpartum women's fatigue between rooming-in and non rooming-in group. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2001; 7(3):241–255.

18. Pugh LC, Milligan R. A framework for the study of childbearing fatigue. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1993; 15(4):60–67.

19. Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2005; 44(2):227–239.

20. Cha ES, Kim KH, Erlen JA. Translation of scales in cross-cultural research: Issues and techniques. J Adv Nurs. 2007; 58(4):386–395.

21. Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995; 33(3):335–343.

22. Ferrans CE, Powers MJ. Quality of life index: Development and psychometric properties. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1985; 8(1):15–24.

23. Hill PD, Aldag JC. Maternal perceived quality of life following childbirth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007; 36(4):328–334.

24. Symon A, Mackay A, Ruta D. Postnatal quality of life: A pilot study using the Mother-Generated Index. J Adv Nurs. 2003; 42(1):21–29.

25. Lacasse A, Rey E, Ferreira E, Morin C, Berard A. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: What about quality of life? BJOG. 2008; 115(12):1484–1493.

26. Neggers Y, Goldenberg R, Cliver S, Hauth J. The relationship between psychosocial profile, health practices, and pregnancy outcomes. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006; 85(3):277–285.

27. Chien LY, Ko YL. Fatigue during pregnancy predicts caesarean deliveries. J Adv Nurs. 2004; 45(5):487–494.

28. Ingstrup KG, Andersen CS, Ajslev TA, Pedersen P, Sorensen TIA, Nohr EA. Maternal distress during pregnancy and offspring childhood overweight. Journal of Obesity. 2012; 2012:462845.

29. Hwang RH. Relationship between maternal fetal attachment and state anxiety of pregnant women in the preterm labor. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2013; 19(3):142–152.

30. Jallo N, Bourguignon C, Taylor AG, Utz SW. Stress management during pregnancy: Designing and evaluating a mind-body intervention. Fam Community Health. 2008; 31(3):190–203.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download