Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to identify related factors of prenatal depression by stress-vulnerability and stress-coping models for pregnant women.

Methods

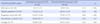

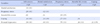

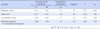

A cross-sectional survey design with a convenience sampling was used. A total of 107 pregnant women who visited a general hospital in a metropolitan city were recruited from August to October, 2013. A structured questionnaire included the Korean version of Beck Depression Inventory II, and the instruments measuring Self-Esteem, Marital Satisfaction, Pregnancy Stress, Stressful Life Events, and Coping. The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-test, Parson's correlation analysis, and stepwise multiple regression.

Results

The mean score of prenatal depression was 11.95±6.2, then showing 19.6% with mild depression, 15.0% with moderate depression, and 0.9% with severe depression on BDI II scale. Prenatal depression had positive correlation with pregnancy stress (r=.55, p<.01), stressful life events (r=.26, p<.01) and negative correlation with self-esteem (r=-.38, p<.01), marital satisfaction (r=-.40, p<.01), and coping (r=-.21, p<.05). Factors of pregnancy stress, self-esteem, stressful life events, and planned pregnancy explained 38% of the total variance of prenatal depression.

Figures and Tables

| Figure 1Research framework of this study based on the stress-vulnerability and stress-coping models. |

Summary Statement

▪ What is already known about this topic?

Depression is one of the most common complications in pregnancy. Several professional organizations now recommend routine screening for prenatal depression.

▪ What this paper adds?

The rate of prenatal depression was 35.5% in this study. Influencing factors of prenatal depression were pregnancy stress, self-esteem, stressful life events, and planned pregnancy.

▪ Implications for practice, education and/or policy

Health providers and professional organizations have to recommend routine screening for prenatal depression.

References

1. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition 2012 [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2012. cited 2014 January 16. Available from: https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/index.do.

2. Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Epidemiological survey of psychiatric illnesses in Korea 2011 [Internet]. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare;2011. cited 2014 January 20. Available from: http://www.korea.kr/main.do.

3. Choi SK, Ahn SY, Shin JC, Jang DG. A clinical study of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 52(11):1102–1108.

4. McKee MD, Cunningham M, Jankowski KR, Zayas L. Health-related functional status in pregnancy: Relationship to depression and social support in a multi-ethnic population. Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 97(6):988–993.

5. Kwon M. Antenatal depression and mother-fetal interaction. J Korean Acad Child Health Nurs. 2007; 13(4):416–426.

6. Kim ES, Ryu SY. The relationship between depression and sociopsychological factors in pregnant women. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2008; 12(2):228–241.

7. Kwon MK, Bang KS. Relationship of prenatal stress and depression to maternal-fetal attachment and fetal growth. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2011; 41(2):276–283.

8. Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Report No.:05-E006-2. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment. North Carolina: RTI Univercity;2005. 02.

9. Kitamura T, Yoshida K, Okano T, Kinoshita K, Hayashi M, Toyoda N, et al. Multicentre prospective study of perinatal depression in Japan: Incidence and correlates of antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006; 9(3):121–130.

10. Bowen A, Muhajarine N. Antenatal depression. Can Nurse. 2006; 102(9):26–30.

11. Brandon AR, Trivedi MH, Hynan LS, Miltenberger PD, Labat DB, Rifkin JB, et al. Prenatal depression in women hospitalized for obstetric risk. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 69(4):635–643.

12. Kim HW, Jung YY. Influencing factors on antenatal depression. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2010; 16(2):95–104.

13. Ingram RE, Luxton DD. Vulnerability-stress models. In : Hankin B, Abela JRZ, editors. Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective. New York: Sage Publications;2005. p. 32–46.

14. Brummelte S, Galea LA. Depression during pregnancy and postpartum: Contribution of stress and ovarian hormones. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010; 34(5):766–776.

15. Rosenburg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press;1965.

16. Agoub M, Moussaoui D, Battas O. Prevalence of postpartum depression in a Moroccan sample. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005; 8(1):37–43.

18. Hong KE, Jeong DU. Construction of Korean 'social readjustment rating scale'-A methodological study-. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1982; 21(1):123–136.

19. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company Verlag;1984.

20. Sung HM, Kim JB, Park YN, Bai DS, Lee SH, Ahn HN. A study on the reliability and the validity of Korean version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II(BDI-II). J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry. 2008; 14(2):201–212.

21. Jon BJ. Self-esteem: A test of its measurability. Yonsei Nonchong. 1974; 11(1):107–130.

22. Roach AJ, Frazier LP, Bowden SR. The marital satisfaction scale: Development of a measure for intervention research. J Marriage Fam. 1981; 43(3):537–546.

23. Huh YJ. A study on the types of marital relationship and marital satisfaction [master's thesis]. Seoul: Sungshin Women's University;1996.

24. Ahn HL. An experimental study of the effects of husband's supportive behavior reinforcement education on stress relief of primigravidas. J Nurs Acad Soc. 1985; 15(1):5–16.

25. Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. J Behav Med. 1981; 4(2):139–157.

26. Kim KS. A Study on the relationship between anxiety and coping in open heart surgery patients. J Korea Community Health Nurs Acad Soc. 1989; 3(1):67–73.

27. Prady SL, Pickett KE, Croudace T, Fairley L, Bloor K, Gilbody S, et al. Psychological distress during pregnancy in a multi-ethnic community: Findings from the born in Bradford cohort study. PLoS One. 2013; 8(4):e60693.

28. Kingston D, Heaman M, Fell D, Dzakpasu S, Chalmers B. Factors associated with perceived stress and stressful life events in pregnant women: Findings from the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey. Matern Child Health J. 2012; 16(1):158–168.

29. Lee JA, Kim YH. Personality characteristics, social support, and coping strategies in stress-adjustment: Structural model approach. Korean Psychological Association;2002. p. 549–561.

30. Park JY. The effects of collage-oriented prenatal art therapy program on the stress of pregnant women. Korean J Arts Ther. 2011; 11(2):1–23.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download