Abstract

Purpose

Dysmenorrhea is a menstrual condition characterized by severe and frequent cramps and pain. Effective treatment methods for dysmenorrhea are not yet fully understood. This research compares the effects of pain killers and heated red bean pillows.

Methods

Data were got on demographic data, menstrual cycle status, and activities of daily living (ADLs) limitations, dysmenorrhea severity and menstrual pain scores. Following a 10% drop-out rate, 44 young women satisfied the inclusion criteria. To prevent any bias, the experimental and control groups were selected from different campuses. We used two sizes of red bean pillows: 15×18 cm, weighing 400g; and 13×11.5 cm, weighing 220g. For analysis, we used IBM SPSS statistics 19.0.

Results

Ninety-nine point seven percentage of total subjects reported moderate to severe dysmenorrhea and 63.6% reported as moderate to severe daily activities limitations. The mean pain score with visual analogue scale was 80.2±9.42 of 100 and 86.4% used pain killers to alleviate menstrual discomfort in all the subjects. In both groups, all three variables showed significant improvement and the Moos's Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (MDQ) scores changed significantly between menstrual and post-menstrual time point at within groups and not significantly different at premenstrual and menstrual time point at between groups. However, the MDQ score was significantly higher in experimental group than control group at post-menstruation time point and the degree of satisfaction was higher in the control group.

Conclusion

This research shows that red-bean pillows on the abdomen are effective in assisting the ADL and diminishing pain severity. With regard to its safety the study indicates it can be a convenient and safe option for female students with menstrual discomfort in schoolas a non-pharmacological self-help.

Dysmenorrhea is a menstrual condition characterized by severe and frequent menstrual cramps and pain. It is the most common gynaecologic disorder among female adolescents, with a prevalence rate of 60~89.5% (Cakir, Mungan, Karakas, Girisken, & Okten, 2007; Mishra & Mukhopadhyay, 2012). Common dysmenorrhea symptoms are tension, irritability, depression, anxiety, bloating, abdominal cramps, tender breast, joint pain, and headaches (Banikarim, Middleman, GeVner, & Hoppin, 2011; Smith, Kaunitz, Barbieri, & Barss, 2011). It lessens the quality of life, increases the need for medical treatment, and prevents women from attending school or work (Burton, Morrison, & Wertheimer, 2003). Primary dysmenorrhea is a painful menses in a normal pelvic anatomy and usually begins during adolescence (French, 2005).

Worldwide, the prevalence rate of dysmenorrhea can be anywhere between 40~95%: 60% of 1546 surveyed women in Canada (Burnett et al., 2005), more than 50% of 2262 surveyed women in India (Patel, Tanksale, Sahasrabhojanee, Gupte, & Nevrekar, 2006), 79% of college students in Japan (Yamamoto, Okazaki, Sakamoto, & Funatsu, 2009), 72.1% of Turkish college student (Pinar, Colak, & Oksuz, 2011), and 78.3% of adolescent girls in Korea (Kim, Lim, Woo & Kim, 2008).

Many dysmenorrhea treatment methods have been tried and the most common methods of the administration are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). There is some evidence showing that NSAIDs are significantly effective in relieving pain in women with dysmenorrhea (Marjoribanks, Proctor, Farquhar, & Derks, 2010). However, anti-inflammatory medications are associated with a number of side effects (Tramer, Moore, Reynolds, & McQuay, 2000). Because the underlying causes and effective treatment methods for dysmenorrhea are still not fully understood and many adolescents continue to take pain medications.

There were some intervention methods tried by researches that complimented the usual analgesic therapy: regular exercise and activity, acupressure, yoga, etc. (Mahvash et al., 2012). Also, acupressure at the SP6 and SP8 points was reported as being effective (Chang & Jun, 2003; Gharloghi, Torkzahrani, Akbarzadeh, & Heshmat, 2012). Three yoga positions (cobra, cat, and fish) were found to be effective in reducing the severity and duration of primary dysmenorrhea (Rakhshaee, 2011). Akin et al. (2004) reports that continuous, low-level, topical heat therapy afforded better results than acetaminophen in the treatment of dysmenorrhea.

However, the above intervention methods might not be practical for college students in the classroom. To be practical, a treatment needs to be somewhat portable. Microwave a red bean pillow for three minutes and it will stay warm for up to one hour. We planned to see how well they worked in relieving painful symptoms. We found red bean is good for keeping heat and thought to apply heated red bean pillow on the abdomen as they needed.

When menstruation occurs, the uterus contracts to shed its lining. Prolonged contraction of the uterine muscles sometimes causes painful cramping. Heat therapy works by relaxing the muscles of the uterus, thereby easing pain and other dysmenorrhea symptoms (Akin et al., 2004). The main objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of heated red bean pillows in the treatment of dysmenorrhea in college age women. We hoped to provide supporting evidence to promote coping strategy for non-pharmacological self-help.

Recruitment took place over a period of approximately two weeks. Those who fitted the criteria were then informed about the study and personally invited to participate. The applications and questionnaires were supervised by a research assistant. To be eligible for this study, the women were required to be in the first to third grade and not taking lectures from the researcher. The selection criteria were as follows: ADL limitations above the normal level, severe menstrual pain, and a subjective pain score higher than 60 points related to menstruation (Figure 1).

G-power analysis showed intervention numbers should be 39 subjects. However, following a 10% drop-out rate, 44 young women satisfied the inclusion criteria. We assigned 22 women heated red bean pillows and administered pain killers to the other 22 by the location of campus. To prevent contamination, campus A students were classified as the experimental group and campus B students were classified as the control group. We provided informed consent information to every student and explained that they could drop out whenever they wanted.

We ordered the red bean pillows in two sizes: 15×18 cm, weighing 400 g; and 13×11.5 cm, weighing 220 g. After placing the red bean pillows in the microwave for three minutes they stayed warm for one hour (Figure 2).

We used woman's Tylenol® as a pain killer for the analgesic control group and followed the community pharmacist's advice on how to administer it. Each pill consisted of acetaminophen (500 mg) and pamabrom (25 mg). We explained to the group that they must only take one pill at a time and a maximum of two pills per day.

The outcome variables were limited to ADLs, dysmenorrhea severity with MDQ, and pain score with a visual analog scale (VAS) for each participant. To compare the availability, we measured the satisfaction degree. An anonymous self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data on demographics, menstrual cycle status, dysmenorrhea severity and menstrual pain score. Menstrual discomfort scores were obtained using the Korean version of Moos's Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (MDQ) (Moos, 1968). This scale was composed of 37 items, 6-point scales, and Cronbach's α=.93 at development and .96 in this study.

Interventions and data collection were carried out from 15 Nov to 13 Dec after getting the baseline data during Oct 27 to Nov 7 2011.We explained to the subjects to fill out by themselves the questionnaire at pre-menstruation (first day of menstruation), menstruation (second or third day of menstruation) and post-menstruation period (final day of menstruation).We collected the data till they finished their one cycle menstruation. We gave vitamin C tablets to participants as a gift.

We used IBM's SPSS/WIN statistics 19.0 program. Frequency and percentage of dysmenorrhea were calculated by descriptive analysis. Homogeneity of both groups on limitations in ADLs, dysmenorrhea severity, and pain score were evaluated by χ2 and t-test. We used a paired t-test to ascertain pre- and post-treatment differences on any limitation in ADLs, dysmenorrhea severity, and pain scores in both groups. The degree of satisfaction on the intervention methods of both groups was analyzed by χ2.

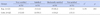

We analyzed homogeneity on 3 variables of limitation of ADLs, severity on dysmenorrhea and pain score with VAS. Table 1 showed that there were no significant differences in both groups.

Sixty-three-point-six percent of the 44 students reported limitations on ADLs as moderate / severe and 99.7% of students reported moderate / severe pain. The mean of the pain score with VAS was (80.2±9.42) and 86.4% of all the subjects used a pain killer to relieve menstrual discomfort. The MDQ score was (104.6±39.4) in the control group and (111.9±34.5) in the experimental group at the baseline.

After homogeneity was confirmed, we evaluated three outcomes: limitations of ADLs, severity of dysmenorrhea, and pain score with VAS. In the experimental group showed improvement at a statistically significant level in all three variables: ADLs limitation (t=2.94, p<.01), severity of dysmenorrhea (t=7.60, p<.001), and pain score (t=4.61, p<.001). In the control group also showed improvement at a statistically significant level in all three variables: ADLs limitation (t=3.48, p<.01), severity on dysmenorrhea (t=7.48, p<.001), and pain score (t=9.21, p<.001) (Table 2).

In comparing within groups, MDQ scores changed significantly from menstrual to post-menstrual time point: 120.1 (31.5) to 82.7 (82.7) in the red bean group (F=6.71, p<.001), and 107.2 (38.1) to 61.2 (31.9) in the pain killer group (F=6.58, p<.001). While it was not significant change in pain killer group, it showed a significant tendency in the red bean group during pre-menstruation to menstruation time point (t=2.00, p=.059).

In comparing inter-groups, there were no significant differences at the premenstrual period or at the menstrual period. However, at the post-menstrual period, the MDQ score was significantly higher in experimental group than that of control group at post-menstruation (F=4.93, p<.05) (Figure 3). So the hypothesis the red bean group will get lower score in the MDQ score than that of the pain killer group was rejected at post-menstruation (Figure 3).

Though both methods, red bean pillows and pain killers, were effective in relieving dysmenorrhea symptoms, the degree of satisfaction was higher in the pain killer group than in the red bean pillow group, and this difference was statistically significant (χ2=14.50, p<.01) (Table 3).

Common dysmenorrhea symptoms are tension, irritability, depression, anxiety, bloating, abdominal cramps, tender breasts, joint pain, and headaches (Banikarim et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2011). Affected women experience sharp, intermittent spasms of pain, usually concentrated in the suprapubic area (AnandhaLakshmi, Priy, Saraswathi, Saravanan, & Ramamchandran, 2011). The uterus contracts frequently and dysrhythmically, with increased basal tone and increased active pressure. Uterine hypercontractility, reduced uterine blood flow and increased peripheral nerve hypersensitivity induce pain (Dawood, 2006).

There were some intervention methods that were reported to be effective. In other countries, alternative therapies such as regular physical activity (Mahvash et al., 2012), acupressure at the SP6 and SP8 points (Gharloghi et al., 2012) and three yoga positions (Rakhshaee, 2011). Also aroma therapy (Han, Hur, Buckle, Choi, & Lee, 2006), acupressure (Jun, Chang, Kang, & Kim, 2007) reported as effective interventions in our country. Recent meta-analysis supports the effect of these alternative methods on menstrual distress (Kim, Park, & Oh, 2013). Shin et al. (2012) suggests that the direct cause of dysmenorrhea might not be changes in bioactive substances in the body-such as hormone imbalances, decreases in serotonin levels, or excessive prostaglandin production-but abnormal functioning of parts of the smooth muscles in the uterus following a long-term blood supply deficiency to the smooth muscle tissue. So, the method of applying heat to the abdominal muscles that was practiced in this study might relax the smooth muscles in the uterus (Hosono et al., 2010). In this respect, heat application makes sense. When compared to other heat generating methods, heated red bean pillows are the most convenient for college women to use during their busy school schedule.

We found that heated red bean pillows had the effect on reducing pain as pain killers had during the menstrual period, but was not the same during the post-menstrual period in respect to menstrual distress. That is, the red bean pillow had an effect on the abdomen during menstruation. Concurring with other research, we found that continuous, low-level, topical heat therapy was superior to acetaminophen in treating dysmenorrhea (Akin et al., 2004) and heat patches containing iron chips have comparable analgesic effects as ibuprofen (Navvabi-Rigi et al., 2012). These results confirmed the effect of the heat therapy for primary dysmenorrhea. This research supported previous research results and added heated red bean pillows as a safe and convenient method for college women to use as they want to apply.

Other various complimentary methods to relieve dysmenorrhea symptoms significantly reduce the types and numbers of drugs that need to be taken. So we need to do further study with controls for extrinsic factors.

The students with ADLs limitation of moderate / severe was 63.6% in this study, which was higher than the 22.1% of students with dysmenorrhea in India (Anandha Lakshmi et al., 2011). After two types of interventions, both groups evaluated ADLs limitation as improved over baseline levels. This difference was attributed to the risk factors, which we didn't consider as controllable variables in this study. It is known that the risk factors for dysmenorrhea during the <20 years are nullipara, heavy menstrual flow, smoking, high/upper socioeconomic status, some attempts to lose weight, physical activity, disrupting social networks, depression, and anxiety (Harlow & Park, 1996; Nohara, Momoeda, Kubota, & Nakabayashi, 2011). It needs to be far studied including risk factors in detail.

This research suggests that heat therapy using a heated red bean pillow can be an effective and satisfactory option for treating dysmenorrhea in young women.

This research shows that heat therapy applied to the abdomen using heated red bean pillows was effective in helping the recipients carry out daily activities and in diminishing their pain. The effect of the heated red bean pillows to relieve the MDQ pain was shown at pre-menstruation and menstruation time point not at post-menstruation time point compared to pain killer group. With regard to side effect of drug, the study indicates heated red bean pillows can besafe and convenient optionand expands nursing intervention methods for female students with menstrual discomfort in school as a non-pharmacological self-help.

Figures and Tables

Figure 3

Comparison of MDQ (Menstrual Distress Questionnaire) score at 3 periods by within & between groups.

References

1. Akin M, Price W, Rodriguez G Jr, Erasala G, Hurley G, Smith RP. Continuous, low-level, topical heat wrap therapy as compared to acetaminophen for primary dysmenorrhea. J Reprod Med. 2004; 49:739–745.

2. Anandha Lakshmi S, Priy M, Saraswathi I, Saravanan A, Ramamchandran C. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhea among medical students and its association with college absenteeism. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011; 2:1011–1016.

3. Banikarim C, Middleman AB, GeVner M, Hoppin AG. Primary dysmenorrhea in adolescents. 2011. Retrieved December 1. from http://www.uptodate.com.

4. Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, Feldman K, Grenville A, Lea R, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005; 27:765–770.

5. Burton WN, Morrison A, Wertheimer AI. Pharmaceuticals and worker productivity loss: A critical review of the literature. J Occup Environ Med. 2003; 45:610–621.

6. Cakir M, Mungan I, Karakas T, Girisken I, Okten A. Menstrual pattern and common menstrual disorders among university students in Turkey. Pediatr Int. 2007; 49:938–942.

7. Chang SB, Jun EM. Effects of SP-6 acupressure on dysmenorrhea, cortisol, epinephrine and norepinephrine in the college students. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2003; 33:1038–1046.

8. Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: Advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006; 108:428–441.

9. Gharloghi S, Torkzahrani S, Akbarzadeh AR, Heshmat R. The effects of acupressure on severity of primarydysmenorrhea. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012; 6:137–142. http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S27127.

10. French L. Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2005; 71:285–291.

11. Han SH, Hur MH, Buckle J, Choi J, Lee MS. Effect of aromatherapy on symptoms of dysmenorrhea in college students: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2006; 12:535–541.

12. Harlow SD, Park M. A longitudinal study of risk factors for the occurrence, duration and severity of menstrual cramps in a cohort of college women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996; 103:1134–1142.

13. Hosono T, Takashima Y, Morita Y, Nishimura Y, Sugita Y, Isami C, et al. Effects of a heat- and steam-generating sheet on relieving symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea in young women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010; 36:818–824. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01237.x.

14. Jun EM, Chang S, Kang DH, Kim S. Effects of acupressure on dysmenorrhea and skin temperature changes in college students: A non-randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007; 44:973–981.

15. Kim HO, Lim SW, Woo HY, Kim KH. Premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhea in Korean adolescent girls. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 51:1322–1329.

16. Kim JH, Park MK, Oh MR. Meta-analysis of complementary and alternative intervention on menstrual distress. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2013; 19:23–35. http://dx.doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2013.19.1.23.

17. Mahvash N, Eidy A, Mehdi K, Zahra MT, Mani M, Shahla H. The effect of physical activity on primary dysmenorrhea of female university students. World Appl Sci J. 2012; 17:1246–1252.

18. Marjoribanks J, Proctor M, Farquhar C, Derks RS. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; (1):CD001751. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001751.pub2.

19. Mishra SK, Mukhopadhyay S. Socioeconomic correlates of reproductive morbidity among adolescent girls in Sikkim India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012; 24:136–150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1010539510375842.

20. Moos RH. The development of a menstrual questionnaire. Psychosom Med. 1968; 30:853–867. Retrieved January 10, 2012, from http://www.psychosomaticmedicine.org/content/30/6/853.full.pdf.

21. Navvabi Rigi S, Kerman-Saravi F, Navidian A, Safabakhsh L, Safarzadeh A, Khazaian S, et al. Comparing the analgesic effect of heat patch containing iron chip and ibuprofen for primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Womens Health. 2012; 12:25. Retrieved November 28, 2012, from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6874/12/25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-12-25.

22. Nohara M, Momoeda M, Kubota T, Nakabayashi M. Menstrual cycle and menstrual pain problems and related risk factors among Japanese female workers. Ind Health. 2011; 49:228–234.

23. Patel V, Tanksale V, Sahasrabhojanee M, Gupte S, Nevrekar P. The burden and determinants of dysmenorrhea: A population-based survey of 2262 women in Goa, India. BJOG. 2006; 113:453–463.

24. Pinar G, Colak M, Oksuz E. Premenstrual syndrome in Turkish college students and its effects on life quality. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2011; 2:21–27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2010.10.001.

25. Rakhshaee Z. Effect of three yoga poses (cobra, cat and fish poses) in women with primary dysmenorrhea: A randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011; 24:192–196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2011.01.059.

26. Shin YI, Kim NG, Park KJ, Kim DW, Hong GY, Shin BC. Skin adhesive low-level light therapy for dysmenorrhoea: A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled, pilot trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012; 286:947–952. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2380-9.

27. Smith RP, Kaunitz AM, Barbieri RL, Barss VA. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of primary dysmenorrhea in adult women. Retrieved December 1, 2012. from http://www.uptodate.com.

28. Tramer MR, Moore RA, Reynolds DJ, McQuay HJ. Quantitative estimation of rare adverse events which follow a biological progression: A new model applied to chronic NSAID use. Pain. 2000; 85:169–182.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download