Abstract

Purpose

This study was aimed to examine the gap between predicted cesarean section rate and real cesarean section rate and it's determining factors of 44 tertiary hospitals.

Method

This study is a cross-sectional analysis using the data of 25,623 deliveries in 2009 drawn from homepage of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Data were analyzed with t-test, F-test, Scheffe? test, and logistic regression.

Result

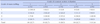

There were statistically significant differences in the gap of cesarean section rate (more gap indicates higher quality of delivery) by grade of nurse staffing and delivery cases. Hospitals with nurse staffing grade 1 to 2 had more possibility to be classified into higher grade in quality of delivery (OR 5.67, 95% CI 1.07~30.08). Also hospitals with over 500 delivery cases had more possibility be classified into higher grade in quality of delivery (OR 4.92, 95% CI 1.14~21.23, respectively).

Conclusion

The finding suggests that grade of nurse staffing may influence the real cesarean section rate because nurses do a vital role to prevent unnecessary cesarean section. Further study is required to provide evidence that nurse staffing influence on patient outcome and cost-effectiveness in order to obtain adequate number of nursing staffs.

Figures and Tables

Summary Statement

▪ What is already known about this topic?

To decrease cesarean section rate, WHO recommends hospitals to deploy one nurse per mother for supportive care during delivery process. The Korean government has evaluated the quality of delivery based on the gap between predicted cesarean section rate and real cesarean section rate among superior hospitals.

▪ What this paper adds?

There were significant differences in the gap of Cesarean section rates among the grades of nurse staffing and delivery cases in hospitals. Hospitals with better grade of nurse staffing and over 500 delivery had more possibility to be classified into a higher grade in quality of delivery.

▪ Implications for practice, education and/or policy

The influence of nurse staffing may improve the quality of delivery because nurses do a vital role to prevent unnecessary cesarean section during the delivery process. Hospitals need to consider nurse staffing to enhance the quality of delivery.

References

1. AbouZahr C, Wardlaw T. Maternal mortality at the end of a decade signs of progress? Bull World Health Organ. 2001. 79:561–568.

2. Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Lake ET, Cheney T. Effects of hospital care environments on patient mortality and nurse outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2008. 38:223–229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.NNA.0000312773.42352.d7 PMCID: PMC2586978.

3. Almeida S, Bettiol H, Barbieri MA, Silva AA, Ribeiro VS. Significant differences in cesarean section rates between a private and a public hospital in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2008. 24:2909–2918.

4. Buchan J. A certain ratio? Minimum staffing ratios in nursing: A report for the Royal College of Nursing. 2004. London: RCN.

5. Chalmers B, Mangiaterra V, Porter R. WHO principles of perinatal care: The essential antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum care course. Birth. 2001. 28:202–207.

6. Chen CS, Lin HC, Liu TC, Lin SY, Pfeiffer S. Urbanization and the likelihood of a cesarean section. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008. 141:104–110.

7. Childbirth Connection. Listening to mothers II: Report of the second national U.S. survey of women's childbearing experiences. 2006. America: Author.

8. Forster DA, McLachlan HL, Yelland J, Rayner J, Lumley J, Davey MA. Staffing in postnatal units: Is it adequate for the provision of quality care? Staff perspectives from a state-wide review of postnatal care in Victoria, Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006. 6:83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-83.

9. Garcia FA, Miller HB, Hugginns GR, Gordon TA. Effects of academic affiliation and obstetric volume on clinical outcome and cost of childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 97:567–576.

10. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Evaluation and follow up report on cesarean section in Korea. 2009a. Seoul: Author.

11. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Cesarean section rate evaluation result by hospitals. 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011. from http://www.hira.or.kr/rec_infopub.hospinfo.do?method=listDiagEvl&pgmid=HIRAA030004000000.

12. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Nurse staffing grade by hospitals. 2009b. Retrieved May 1, 2009. from http://www.hira.or.kr/rdc_hospsearch.hospsearch.do?method=hospital&pgmid=HIRAA030002000000.

13. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. 2010 report about appropriateness of cesarean: Preliminary test payment for performance. 2010. Seoul: Author.

14. Hodnett ED, Stremle R, Willan AR, Weston JA, Lowe NK, Simpson KR, et al. SELAN (Structured Early Labour Assessment and Care by Nurses) Trial Group. Effect on birth outcomes of a formalized approach to care in hospital labour assessment units: International, randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2008. 337:a1021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1021.

15. Hopkins K. Are Brazilian women really choosing to deliver by cesarean? Soc Sci Med. 2000. 51:725–740.

16. Hugonnet S, Villaveces A, Pittet D. Nurse staffing level and nosocomial infections: Empirical evaluation of the case-crossover and case-time-control designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2007. 165:1321–1327.

17. Kane RL, Shamliyan T, Mueller C, Duval S, Witt T. Nursing staffing and quality of patient care. AHRQ publication 07-E005. 2007. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

18. Kim YM, Go SK. Factors Determining Cesarean Section Frequency Rates of the OBGY Clinics in Metropolitan Area. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2002. 18:389–401.

19. Kim YM, Cho DS, Cha BH, Hur MH, Oh HS, Kim EY. A study of the health policy for the cesarean section rate reduction. 2007. Seoul: Ministry for Health and Welfare.

20. Kim YM, Kim JY, June KJ, Ham EO. Changing trend in grade of nursing management fee by hospital characteristics: 2008-2010. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2010. 16:99–109.

21. Lee SI, Khang YH, Yun S, Jo MW. Rising rates, changing relationships: caesarean section and its correlates in South Korea, 1988-2000. BJOG. 2005. 112:810–819.

22. Librero J, Peiró S, Calderón SM. Inter-hospital variations in cesarean sections. A risk adjusted comparison in the Valencia public hospitals. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000. 54:631–636.

23. Lin HC, Xirasagar S, Liu TC. Doctors' obstetric experience and Caesarean section (CS): Does increasing delivery volume result in lower CS likelihood? J Eval Clin Pract. 2007. 13:954–957.

24. Ministry for Health and Welfare. Notification No. 2006-105. 2006. 12. 18.

25. Ontario Women's Health Council. Attaining and maintaining best practices in the use of caesarean sections-An analysis of four Ontario hospitals. 2000. Toronto, Ontario: Author.

26. Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development. 2009 Health data CD. 2009.

27. Park JO, Kim HY, Roh GS, Roh YD, Park MB, So JE, et al. Comparison of nursing activity time according to the change in grade of nursing management fee in one university hospital. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2010. 16:95–105.

28. Wax JR, Cartin A, Pinette MG, Blackstone J. Patient choice cesarean-the Maine experience. Birth. 2005. 32:203–206.

29. West E, Mays N, Rafferty AM, Rowan K, Sanderson C. Nursing resources and patient outcomes in intensive care: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009. 46:993–1011.

30. Yun SG, Park YJ, Kim KH, Han CH. Evaluation on the performance of nursing in according to the nursing grade of hospitals. Korean J Hosp Manage. 2010. 15(3):1–16.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download