Abstract

We herein report on a patient with a cerebral aneurysm located at the petrous portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA). An 18-year-old male, previously diagnosed with neurofibromatosis, was referred to our emergency service complaining of severe headache, pulsatile tinnitus, nausea, and vomiting which occurred suddenly. Neuro-radiological studies including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the cerebral artery showed a large aneurysm arising from the petrous segment of the left ICA. He was treated with a neuro-interventional technique such as intra-arterial stenting and coil embolization for the aneurysm. Several days after the interventional treatment, his symptoms were resolved gradually except for a mild headache.

Symptomatic unruptured aneurysm at the petrous portion of the ICA is rare, and our patient was treated successfully using a neuro-intervention technique. Therefore, we describe a case of a petrous aneurysm treated with endovascular coils without compromising the ICA flow, and review the literature.

Aneurysms arising at the petrous internal carotid artery (ICA) are rare, and their pathogenesis remains uncertain. The mechanisms in formation of aneurysms at the petrous portion of the carotid artery: mycotic, traumatic, and congenital. Infection and inflammation occurring in the middle ear can cause erosion of bony structures leading to involvement into the artery adventitia, which can weaken and make room for aneurysmal expansion of the middle ear.2)10)11)14)

In addition, Systemic connective tissue diseases like Marfan's syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome are an important source of aneurysmal formation of the systemic arteries. Neurofibromatosis type I (NF-I), or von Recklinghausen disease, is an autosomal dominant disorder affecting one in 3,000 individuals.12) Vascular lesions of medium and large-sized arteries and veins are a well-recognized, albeit rare, feature.4)7) Internal carotid artery (ICA) aneurysms are most commonly vasculopathy with NF-I, and operative treatment of patients with symptomatic disease or large aneurysms is safe, effective, and durable.13)

We treated a case of a symptomatic petrous ICA aneurysm with NF-I. We also review the literature of case reports associated with petrous ICA aneurysms.

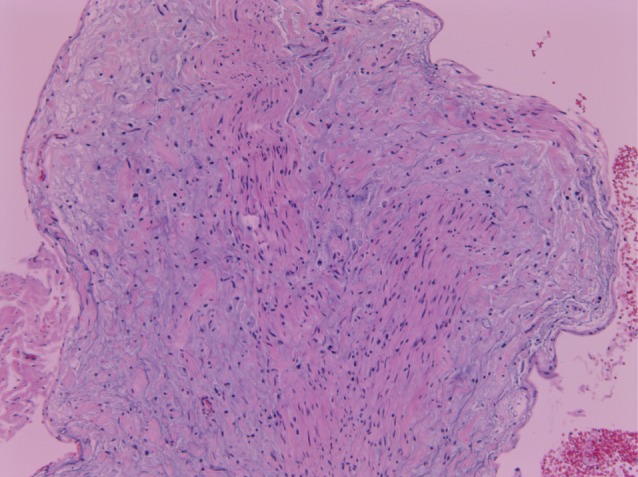

An 18-year-old male, previously diagnosed with neurofibromatosis (Fig. 1), was referred to our emergency service complaining of severe headache, tinnitus with nausea, and vomiting which occurred suddenly. He presented no other symptoms except severe headache and he had no traumatic history or other external wounds. His oral cavity and cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal, and nervous system examinations were normal and there was no lymphadenopathy. Chest radiography and abdomen-pelvis CT showed no abnormality. Laboratory testing included a complete blood cell count (CBC) with a hemoglobin of 15.7 gm/dL, a platelet count of 299,000/mm3, and a white blood cell count of 8,700/mm3, with 2.3% eosinophils. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and CRP were within the normal limits. He was not drinking or smoking, and his neurofibromatosis had been well controlled for a long time. The CT angiogram showed an aneurysm of the petrous segment of the left internal carotid artery (Fig. 2A). A magnetic resonance image showed a large aneurysm arising from the petrous segment of the left internal carotid artery (Fig. 2B, 3).

To preserve the carotid artery and exclude the aneurysm from the native circulation, a stent was deployed in the left petrous carotid artery across the aneurysm neck (Fig. 4A), and 2,000 U of intravenous heparin sodium was then administered. A microcatheter was advanced across the stent wall and into the aneurysm. Then, one Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) with (10) mm × (34) cm length, two GDCs with (9) mm × (33) cm length, two GDCs with (8) mm × (16.1) cm length, three GDCs with (7) mm × (13.9) cm length, and three GDCs with (6) mm × (11.9) cm length were placed into the aneurysm. A final angiographic image showed that there was no aneurysm opacification and left internal carotid artery patency (Fig. 4B). He was discharged after four days with a prescription for 75 mg/day of clopidogrel and 100mg/day of aspirin for 14 days. There was no occurrence of neurological sequelae.

The petrous portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA) is defined as the continuation of the cervical area of the ICA where it passes the petrous portion of the temporal bone via the carotid canal. The cervical portion is relatively mobile but the petrous portion is not, thus the cervical-to-petrous transition of the carotid artery can be susceptible to stretch forces, which in turn cause this portion to ascribe to unexpected dissections and pseudoaneurysms.15) In addition, petrous ICA is encircled with several clinically significant structures, including the cochlea, middle ear, eustachian tube, gasserian ganglion, geniculate ganglion, greater superficial petrosal nerve, and jugular fossa. Therefore, because of their anatomical position, they can present with specialized symptoms, such as cranial nerve palsies, tinnitus, massive otorrhea or epistaxis rather than intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage. Mangat et al. described a case of a petrous ICA aneurysm with Honer's syndrome and sixth nerve palsy, which they treated with an external-internal carotid artery bypass graft and aneurysm trapping and the patient recovered from the described symptoms.9)

This case of symptomatic unruptured petrous ICA aneurysm is also associated with NF-I. Actually, NF-I is an autosomal dominant disorder resulting from a mutation of the NF-I gene located on the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q11.2).4)5)7) Vascular abnormalities are a well-recognized manifestation of NF-I. It may be that arterial stenoses or aneurysms in these patients occur by a dynamic process of cellular proliferation, degeneration, healing, smooth muscle loss, and fibrosis. Neurofibromin expression has been demonstrated in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Many cases of petrous ICA aneurysm accompanied by systemic vasculopathies have been reported. Cohen et al reported on a petrous ICA pseudoaneurysm in bilateral fibromuscular dysplasia, treated with a self-expanding covered stent and achieved good post-operative vascular patency.1) Yi et al.16) reported on a case involving an infant who presented with a petrous ICA aneurysm with tuberous sclerosis (TS) complex. They emphasized that symptomatic petrous ICA aneurysm with TS must be considered in treatment with surgical or endovascular management.

On the other hand, complications of active bleeding with ruptured petrous ICA aneurysms were not infrequently reported. Oyama reported a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the petrous ICA caused by chronic otitis media (COM). Based on the amount of petrous bone destruction around the ICA, he believed that inflammation from COM had induced the pseudoaneurysm.14) Endo et al. reported a case of a ruptured petrous ICA aneurysm that presented with massive epistaxis and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) after transsphenoidal surgery and radiotherapy. In general, rupture of a petrous ICA aneurysm should not result in SAH because of its anatomical position. However their case presented with intracranial hemorrhage because of modified bony structure after a previous transsphenoidal approach operation.3) Petrous ICA aneurysms can sometimes present with hemotympanum.8)

Several therapeutic strategies can be considered as follows: (1) conservative management with regular and serial imaging studies, (2) surgical trapping around the carotid artery and revascularization with a bypass, (3) endovascular balloon occlusion on the internal carotid artery, (4) endovascular embolization with coil placement into the aneurysm, with or without stent assistance, and (5) flow diverting techniques. Patients who are asymptomatic and have an incidental diagnosis can be managed conservatively with regular follow-up. However, patients presenting with acute intracranial or nasopharyngeal hemorrhage should be treated rapidly with a more aggressive therapeutic option, either open surgery or endovascular techniques. In cases of symptomatic patients who present with cranial nerve dysfunctions without an aneurysm rupture, careful analysis of the balance of risk-to-benefit of each procedure is required. Carotid occlusion and surgical morbidity are considered risks of the procedures. Relief around avoiding growth of the aneurysm can be a key benefit. Endovascular strategies can be considered as the first-line therapy for patients who tolerate the balloon occlusion test. Novel endovascular stent technologies, including coil placement with stent-assistance and covered stents, may eliminate the aneurysm while well preserving flow in the parent supply.6) Surgical revascularization with an interpositional high-flow bypass graft is an important strategy for lesions inappropriate for endovascular treatment. The risk of rupture and bleeding, leading to a life-threatening condition is higher in patients with a pseudoaneurysm. Therefore, more aggressive options should be considered for patients with pseudoaneurysm. In addition, because patients who do not have sufficient collateral flow cannot be treated with carotid occlusion, revascularization surgery with bypass is not commonly recommended. In the case of patients who were treated with intra-carotid stents, prolonged anti-aggregation treatment should be considered, which can cause inconvenience for the patients.8)

We reported on a rare case of a cerebral aneurysm located at the petrous portion of the ICA who was treated successfully with endovascular stenting and insertion of coils.

Therapeutic strategies for the aneurysm at the petrous ICA remain unestablished. However, if the aneurysm is symptomatic, particularly when combined with systemic vasculopathy, it will be considered in treatment with diverse treatment options. Therefore, treatment should be tailored to the individual and patient selection is of utmost importance.

References

1. Cohen JE, Grigoriadis S, Gomori JM. Petrous carotid artery pseudoaneurysm in bilateral carotid fibromuscular dysplasia: treatment by means of self-expanding covered stent. Surg Neurol. 2007; 8. 68(2):216–220. discussion 220PMID: 17537488.

2. Ehni G, Barrett JH. Hemorrhage from the ear due to an aneurysm of the internal carotid artery. N Engl J Med. 1960; 6. 262(6):1323–1325. PMID: 13819580.

3. Endo H, Fujimura M, Inoue T, Matsumoto Y, Ogawa Y, Kawagishi J, et al. Simultaneous occurrence of subarachnoid hemorrhage and epistaxis due to ruptured petrous internal carotid artery aneurysm: association with transsphenoidal surgery and radiation therapy: case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2011; 3. 51(3):226–229. PMID: 21441741.

4. Friedman JM, Arbiser J, Epstein JA, Gutmann DH, Huot SJ, Lin AE, et al. Cardiovascular disease in neurofibromatosis 1: report of the NF1 Cardiovascular Task Force. Genet Med. 2002; May-Jun. 4(3):105–111. PMID: 12180143.

5. Hamilton SJ, Friedman JM. Insights into the pathogenesis of neurofibromatosis 1 vasculopathy. Clin Genet. 2000; 11. 58(5):341–344. PMID: 11140831.

6. Horowitz M, Levy E, Hathaway B, Jovin T, Hirsch B. Endovascular treatment of a petrous internal carotid artery aneurysm with hemotympanum and epistaxis using a coronary stent and detachable platinum coils: report of a case. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005; 1. 131(1):61–63. PMID: 15655188.

7. Lin AE, Birch PH, Korf BR, Tenconi R, Niimura M, Poyhonen M, et al. Cardiovascular malformations and other cardiovascular abnormalities in neurofibromatosis 1. Am J Med Genet. 2000; 11. 95(2):108–117. PMID: 11078559.

8. Liu JK, Gottfried ON, Amini A, Couldwell WT. Aneurysms of the petrous internal carotid artery: anatomy, origins, and treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2004; 11. 17(5):E13. PMID: 15633978.

9. Mangat SS, Nayak H, Chandna A. Horner's syndrome and sixth nerve paresis secondary to a petrous internal carotid artery aneurysm. Semin Ophthalmol. 2011; 1. 26(1):23–24. PMID: 21275600.

10. McGrail KM, Heros RC, Debrun G, Beyerl BD. Aneurysm of the ICA petrous segment treated by balloon entrapment after EC-IC bypass. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1986; 8. 65(2):249–252. PMID: 3723184.

11. Morantz RA, Kirchner FR, Kishore P. Aneurysms of the petrous portion of the internal carotid artery. Surg Neurol. 1976; 12. 6(6):313–318. PMID: 1006503.

12. Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol. 1988; 5. 45(5):575–578. PMID: 3128965.

13. Oderich GS, Sullivan TM, Bower TC, Gloviczki P, Miller DV, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, et al. Vascular abnormalities in patients with neurofibromatosis syndrome type I: clinical spectrum, management, and results. J Vasc Surg. 2007; 9. 46(3):475–484. PMID: 17681709.

14. Oyama H, Hattori K, Tanahashi S, Kito A, Maki H, Tanahashi K. Ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the petrous internal carotid artery caused by chronic otitis media. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010; 7. 50(7):578–580. PMID: 20671385.

15. Palacios E, Gómez J, Alvernia JE, Jacob C. Aneurysm of the petrous portion of the internal carotid artery at the foramen lacerum: anatomic, imaging, and otologic findings. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010; 7. 89(7):303–305. PMID: 20628987.

16. Yi JL, Galgano MA, Tovar-Spinoza Z, Deshaies EM. Coil embolization of an intracranial aneurysm in an infant with tuberous sclerosis complex: A case report and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2012; 10. 3:129. PMID: 23227434.

Fig. 2

An approximately 1.5 cm-sized aneurysm located at the petrous portion of the internal cerebral artery on the left side is found on computed tomographic angiography (A) and magnetic resonance angiographic image (B) for cerebral artery.

Fig. 3

Bulbous enlargement of the transverse portion of the internal carotid artery on the left side suggests a large aneurysm with a broad neck in the magnetic resonance image of the cerebral artery.

Fig. 4

A large aneurysm located at the petrous portion of the internal cerebral artery on the left side is shown in the pre-treatment image of digital subtracted angiography (A), and the aneurysm is successfully and fully packed with multiple Guglielmi detachable coils (B) in the digital subtracted angiography.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download