Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to compare clinical findings and outcomes of Enterprise and Solitaire stent-assisted coiling (SAC).

Materials and Methods

Between January 2012 and March 2014, 86 patients (mean age, 60.3 years) harboring 89 aneurysms were treated with Enterprise (n = 57) or Solitaire (n = 32) SAC. The patients' demographics, angiographic results, and clinical outcomes were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

There were no cases of stent navigation, deployment failure, arterial dissection, or intraoperative aneurysmal rupture. Angiographic follow-up imaging was available for 86 (96.6%) aneurysms (Enterprise group, n = 55; Solitaire group, n = 31). Immediate postoperative and follow-up angiographic results showed no flow or only minimal flow into the neck in 83% (Enterprise group, 77.2%; Solitaire group, 93.8%) and 95.3% (Enterprise group, 92.7%; Solitaire group, 100%) of SAC-treated aneurysms, respectively. Both stent groups showed good immediate postoperative and follow-up clinical outcomes. Excepting 2 cases, all patients achieved modified Rankin Scale scores of 0. Coil loop or tail protrusion into the parent artery was observed in 17 (29.8%) and 7 (21.9%) cases in the Enterprise and Solitaire groups, respectively. No statistically significant difference in terms of angiographic results or clinical outcomes was observed between the groups.

Conclusion

Excellent and comparable clinical and angiographic outcomes for wide-neck intracranial aneurysms were achieved using both stents. Because of its higher radial strength and better vessel wall apposition, we cautiously propose that the Solitaire stent may be more effective for SAC of aneurysms harboring a large or severe tortuous parent artery.

As a result of recent, revolutionary developments in endovascular treatment, self-expanding stent-assisted coiling (SAC) is now widely accepted for wide-neck or complex intracranial aneurysms, which are technically challenging for conventional coil embolization.5)9) SAC has various advantages. For example, it creates a barrier which can prevent coil herniation into the parent vessel lumen, facilitates increased overall coil packing density,16) and provides flow diversion. Currently, two self-expanding closed-cell stents, the Enterprise VRD stent (Codman, Miami, FL, USA) and the Solitaire AB stent (Covidien, Irvine, CA, USA), are widely used for SAC of wide-neck or complex intracranial aneurysms. Several studies have reported results relevant to each stent, including clinical and angiographic outcomes, procedural feasibility, and complications.4)5)12)16)18) However, few studies have compared the results of Enterprise and Solitaire SAC for wide-neck or complex intracranial aneurysms. The purpose of this study was to compare Enterprise and Solitaire SAC in terms of several clinical findings and the related follow-up results.

Between January 2012 and March 2014, 94 patients with 98 aneurysms underwent SAC of intracranial aneurysms at our institutions. Nine of the aneurysms were treated with Neuroform SAC and were therefore excluded from this study. The remaining 86 patients (male:female ratio, 19:67; age range, 41-89 years; mean age, 60.3 years) harbored 89 aneurysms, which were treated with Enterprise (57 aneurysms) or Solitaire (32 aneurysms) SAC. SAC was performed for aneurysms with a neck width of ≥ 4 mm or a dome-to-neck ratio of < 2, as well as for broad-based aneurysms that were not approachable via conventional coiling. The stent device employed for SAC was determined according to the endovascular neurosurgeon's preferences, with attention to the easiness of manipulation, delivery, and deployment. This study was approved by our institution's review board and informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

In addition to clinical presentation and patient demographics, data were collected on the aneurysm dimensions, location, morphology (saccular, blister-like, or dissecting aneurysms), parent artery diameter and tortuosity (graded qualitatively by the treating endovascular neurosurgeon: mild, moderate, or severe), description of the stent, delivery and deployment failure of the stent, presence of coil protrusion into the parent artery, thromboembolic events, periprocedural morbidity and mortality, and immediate postoperative and follow-up angiographic results from digital subtraction angiography with 3-dimensional rotational imaging. The immediate postoperative and follow-up clinical outcomes were also evaluated.

Standard follow-up angiography was performed 12 months after SAC. Immediate postoperative and follow-up angiographic results, including degree of aneurysm occlusion and presence of in-stent stenosis or in-stent thrombosis, were assessed according to the Raymond-Roy classification as follows: Class I (no filling of the aneurysm or dome), Class II (residual filling of the neck, but not the dome), and Class III (residual filling of the neck and dome). Clinical outcomes at discharge and follow-up were determined using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS).17) All data were reviewed retrospectively. All of the treated aneurysms were graded independently by two endovascular neurosurgeons.

The modality of treatment was decided by a neurosurgeon and an endovascular neurosurgeon after considering the patient's co-morbidities, clinical status, and surgical feasibility in an interdisciplinary discussion. SAC was performed under general anesthesia in all patients. In unruptured cases, patients were pre-medicated with dual antiplatelet agents: 75 mg of clopidogrel and 100 mg of aspirin daily for seven days before SAC. Subsequently, they received full anticoagulation with heparin during SAC. In cases of rupture, patients were not preloaded with antiplatelet agents and heparin coagulation was delayed until placement of the framing coil. The activated clotting time was kept at 200 to 300 seconds during all procedures. SAC was performed using the "jailing" or "semi-jailing" technique in all cases.11) During stent deployment, we most often performed microcatheter-pullback and microwire-push techniques sequentially in order to optimize stent deployment and minimize stent malposition.6) In cases involving coil loop herniation into the parent artery, the position of the coil loop between the parent artery and the stent was confirmed using 3-dimensional digital subtraction angiography.

After treatment, all patients were prescribed a dual antiplatelet regimen including 75 mg/day of clopidogrel and 100 mg/day of aspirin for 6-12 months, after which they were prescribed only 100 mg/day of aspirin for the rest of their lives. During follow-up, plain images of the skull with the same working projection images of SAC were examined every three months. At 12 months after SAC, cerebral angiography and magnetic-resonance angiography were performed to evaluate the degree of aneurysm occlusion, in-stent stenosis, stent migration, and any need for retreatment.

The Pearson Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used for assessment of between-group differences for demographic and clinical characteristics. The Student t-test was performed for evaluation of the statistical significance of differences in continuous parameters. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of less than 0.05 using SPSS ver. 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)

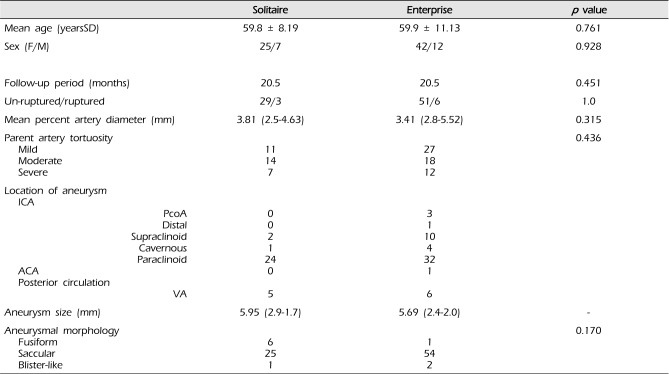

Eighty-nine aneurysms in 86 patients qualified for treatment with SAC (57 in the Enterprise stent group and 32 in the Solitaire stent group). The patients' demographic profiles and aneurysm features are shown in Table 1. Overall, the patient cohort included 19 men and 67 women. The mean age of patients was 60.3 years (range, 41-89 years). Headache was the most common symptom of aneurysms at presentation. In the Enterprise group, the locations of aneurysms were as follows: cavernous segment (n = 4), paraclinoid (n = 32), supraclinoid (n = 10), posterior communicating artery (n = 3), distal internal carotid artery (n = 1), anterior cerebral artery (n = 1), and vertebral artery (n = 6). In the Solitaire group, aneurysms were found in the cavernous segment (n = 1), paraclinoid (n = 25), supraclinoid (n = 1), and vertebral artery (n = 5). Seventy-eight (87.6%) of the aneurysms were located in the anterior circulation and 11 (12.4%) were located in the posterior circulation. The mean aneurysm size was 5.69 mm (range, 2.4-20 mm) in the Enterprise group and 5.95 mm (range, 2.9-17 mm) in the Solitaire group. In the Enterprise group, one aneurysm was fusiform, two had a blister-like shape, and 54 were saccular. In the Solitaire group, six aneurysms were fusiform, one had a blister-like shape, and 25 were saccular. Of the SAC-treated aneurysms, nine were ruptured (10.1%), six in the Enterprise group and three in the Solitaire group. The mean diameter of the parent artery was 3.41 mm (range, 2.5-4.63 mm) in the Enterprise group and 3.81 mm (range, 2.8-5.52 mm) in the Solitaire group. In the Enterprise group, 47 aneurysms had mild or moderate parent artery tortuosity and 12 had severe tortuosity. In the Solitaire group, 25 aneurysms had mild or moderate and seven had severe tortuosity.

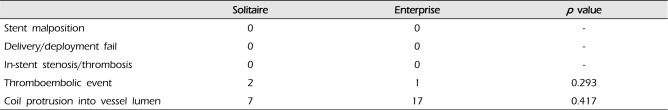

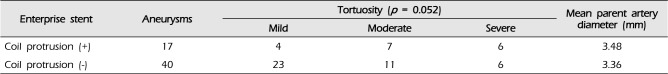

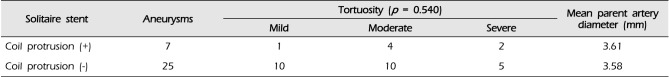

There were no cases of stent navigation or deployment failure in either stent group, and there was no occurrence of arterial dissection and intraoperative aneurysmal rupture. All aneurysms were treated successfully with SAC, without procedural complications. We observed three cases (3.37%) of thromboembolic events, all of which occurred in ruptured aneurysms (Enterprise group, n = 2; Solitaire group, n = 1). However, each case had reverted to its baseline by the last follow-up visit. Coil loop or tail protrusion into the parent artery was observed in 17 cases (29.8%) in the Enterprise group and seven cases (21.9%) in the Solitaire group. No difference in terms of the in-stent thrombosis or stenosis rate, thromboembolic event rate, or overall clinical outcomes was observed between the two stent groups (Table 2).

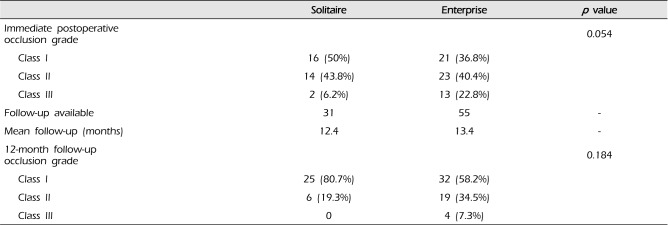

On immediate postoperative angiograms, the occlusion grades in the Enterprise group were as follows: Class I in 21 (36.8%) aneurysms, Class II in 23 (40.4%) aneurysms, and Class III in 13 (22.8%) aneurysms. In the Solitaire group, Class I was observed in 16 (50%) aneurysms, Class II in 14 (43.8%) aneurysms, and Class III in two (6.2%) aneurysms. Angiographic follow-up imaging was available for 86 aneurysms (96.6%; 55 in the Enterprise group and 31 in the Solitaire group) with a mean follow-up period of 12.8 months. On follow-up angiograms, the occlusion grade in the Enterprise group was as follows: Class I in 32 (58.2%) aneurysms, Class II in 19 (34.5%) aneurysms, and Class III in four (7.3%) aneurysms. In the Solitaire group, Class I occlusion was found in 25 (80.7%) aneurysms and Class II occlusion in six (19.3%) aneurysms. There were no cases of in-stent stenosis or stent migration, and there was no need for retreatment in either stent group.

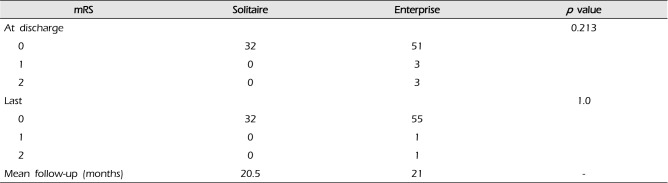

Regarding clinical results, most patients achieved a mRS score of 0 within a mean follow-up period of 20.8 months (Enterprise group, 21 months; Solitaire group, 20.5 months). However, the two ruptured cases in the Enterprise group had mild disability with mRS scores of 2. No statistically significant difference in terms of clinical (p = 1.0) or angiographic results (p = 0.184) was observed between the two stent groups (Table 3, 4).

SAC has become an effective treatment for wide-neck intracranial aneurysms. Self-expandable closed-cell stents, such as the Enterprise and Solitaire, have been used with increasing frequency because of their excellent navigability, flexibility, and high rates of successful deployment.2)4)7)18) They are retrievable and can be repositioned even after full deployment, particularly when using the Solitaire stent.7)9) Previous studies reported excellent results of stent navigation and deployment in both stent groups (success rate: 97.1% for Enterprise stents and 98.1% for Solitaire stents).1)2)9)10)13)15)16)17)18)19) Among our cases, there were no failures or difficulties in stent navigation or deployment. Clinical and angiographic outcomes did not show significant correlation with patient age, patient sex, aneurysm size, or aneurysm type.

Several studies have reported good initial and follow-up angiographic results in both stent groups. In long-term angiographic results, Fargen et al. reported a > 90% rate of occlusion in 81% of 229 patients who underwent Enterprise SAC.4) Examining postoperative angiographic results, Klisch et al. observed a > 90% rate of occlusion in 94% of 53 patients harboring anterior and posterior circulation aneurysms treated with Solitaire SAC.12)13) In our study, the immediate postoperative and follow-up angiographic results showed no flow or minimal flow into the neck in 83% (Enterprise group, 77.2%; Solitaire group, 93.8%) and 95.3% (Enterprise group, 92.7%; Solitaire group, 100%) of aneurysms treated with SAC. These results are consistent with those of previous studies. Izar et al. reported that 36.1% of 84 aneurysms followed in a SAC group showed progressive occlusion on angiographic follow-up imaging.10) This observation further supports the advantages of SAC, as it facilitates increased packing density and thrombosis, as well as providing flow-diversion and a framework for endothelialization. At first, the occlusion grades of aneurysms in the Solitaire group appeared to be superior to those in the Enterprise group. However, this observation may have been associated with our initial clinical inexperience when primarily using the Enterprise stent, and the associated learning curve. Alternatively, this may reflect the relatively poorer vessel wall apposition of the Enterprise stent, as compared with the Solitaire stent.3)11)14) However, there were no significant differences in immediate postoperative (p = 0.054) or follow-up angiographic results (p = 0.184), and there were no cases of in-stent thrombosis/stenosis or stent migration.

In our study, both stent groups showed good immediate postoperative and follow-up clinical outcomes, a finding consistent with previous reports.17) Only 2 patients did not achieve a mRS score of 0. Both of these patients presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage in the Enterprise group and achieved a mRS score of 2. Mocco et al. reported a permanent morbidity rate of 2.8% and a mortality rate of 2% in a study of 141 cases treated with Enterprise SAC.19) Heller and Malek reported a 0% 6-month follow-up permanent morbidity rate and a 0% mortality rate in their study of 62 patients treated with Solitaire SAC.6) In the current study, there were no significant differences between the immediate postoperative (p = 0.213) or follow-up clinical outcomes (p = 1.000) in the 2 stent groups.

Coil loop or tail protrusion into the parent artery (24 cases, 26.9%) was observed more frequently in our study cohort than in the series by Mocco et al. (9.9%), probably because our study included a very small partial coil loop and tail herniation into the parent artery.18) Of 24 aneurysms with coil protrusion (Enterprise group, n = 17; Solitaire group, n = 7), 21 were located in the paraclinoid internal carotid artery and 3 were located in the vertebral artery. Although these events presented more frequently when the parent artery had a relatively larger diameter or severe vessel tortuosity, the differences were not statistically significant (Enterprise group, p = 0.052; Solitaire group, p = 0.540) (Table 5, 6). In an in vitro study of curved vascular models with simulated aneurysm necks, Ebrahimi et al. pointed out that Enterprise stents showed an increasing trend to flatten and kink with vascular curvatures that were more acute.3) This phenomenon may contribute to adverse effects, such as in-stent thrombosis/stenosis or insufficient buttress resulting in coil herniation into the parent artery. As such, we can assume that this phenomenon caused the relatively lower initial occlusion grade of aneurysms in the Enterprise group, as compared with those in the Solitaire group. Heller and Malek, who noted the important role of the delivery technique when employing a Enterprise stent,6) argued that incomplete stent apposition could be minimized in both inner and outer vascular curves by deploying the stent using a dynamic push-pull technique designed to keep the delivery microcatheter centered during deployment. We also used this technique in most cases.

According to data on the functional and physical properties of self-expanding intracranial stents, the Solitaire stent (0.0106 N/mm) has approximately 30% more radial strength than the Enterprise stent (0.0082 N/mm).12)14) In evaluations with 3/4-mm tubes having a 3.9/4.4-mm radius, Krischek et al. reported that the vessel wall apposition of the Solitaire stent is similar to that of the Neuroform stent, but better than that of the Enterprise stent.8)14) These observations may support the idea that the Solitaire stent is superior to the Enterprise considering the role of the buttress in preventing coil herniation, particularly for paraclinoid aneurysms with tortuous vessel curvature or a relatively large parent artery. Krischek et al.14) also mentioned that the area of the Solitaire stent cell is larger than that of the Enterprise stent. Although an increased cell area may cause coil protrusion into the parent artery, this did not occur in our series. Regardless, we observed no statistically significant correlation between coil herniation into the parent artery and clinical or angiographic outcomes in the stent groups. Nonetheless, due to the limitations of our study, including a retrospective design, the limited number of patients, and results of long-term follow-up were lacking, some caution is warranted when interpreting our results.

The results of our study suggest that patients receiving Enterprise and Solitaire SAC for wide-neck intracranial aneurysms show excellent and comparable clinical and angiographic outcomes. Because of its higher radial strength and better vessel wall apposition, we cautiously propose that the Solitaire stent may be more effective than the Enterprise stent for SAC of aneurysms harboring a large or severe tortuous parent artery. More extensive follow-up and a larger patient cohort would be necessary in order to establish any definite conclusions.

References

1. Almekhlafi MA, Hockley A, Wong JH, Goyal M. Temporary Solitaire stent neck remodeling in the coiling of ruptured aneurysms. J Neurointerv Surg. 2013; 11. 5(Suppl 3):iii76–iii78. PMID: 23749789.

2. Chen YA, Hussain M, Zhang JY, Zhang KP, Pang Q. Stent-assisted coiling of cerebral aneurysms using the Enterprise and the Solitaire devices. Neurol Res. 2014; 5. 36(5):461–467. PMID: 24649852.

3. Ebrahimi N, Claus B, Lee CY, Biondi A, Benndorf G. Stent conformity in curved vascular models with simulated aneurysm necks using flat-panel CT: an in vitro study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007; 5. 28(5):823–829. PMID: 17494650.

4. Fargen KM, Hoh BL, Welch BG, Pride GL, Lanzino G, Boulos AS, et al. Long-term results of enterprise stent-assisted coiling of cerebral aneurysms. Neurosurgery. 2012; 8. 71(2):239–244. discussion 244PMID: 22472556.

5. Geyik S, Yavuz K, Yurttutan N, Saatci I, Cekirge HS. Stent-assisted coiling in endovascular treatment of 500 consecutive cerebral aneurysms with long-term follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013; Nov-Dec. 34(11):2157–2162. PMID: 23886748.

6. Heller RS, Malek AM. Delivery technique plays an important role in determining vessel wall apposition of the Enterprise self-expanding intracranial stent. J Neurointerv Surg. 2011; 12. 3(4):340–343. PMID: 21990459.

7. Hopf-Jensen S, Hensler HM, Preiß M, Müller-Hülsbeck S. Solitaire(R) stent for endovascular coil retrieval. J Clin Neurosci. 2013; 6. 20(6):884–886. PMID: 23623613.

8. Hsu SW, Chaloupka JC, Feekes JA, Cassell MD, Cheng YF. In vitro studies of the neuroform microstent using transparent human intracranial arteries. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006; 5. 27(5):1135–1139. PMID: 16687559.

9. Huded V, Nair RR, Vyas DD, Chauhan BN. Stent-assisted coiling of wide-necked intracranial aneurysms using the Solitaire AB stent. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2014; 7. 5(3):254–257. PMID: 25002764.

10. Izar B, Rai A, Raghuram K, Rotruck J, Carpenter J. Comparison of devices used for stent-assisted coiling of intracranial aneurysms. PloS One. 2011; 9. 6(9):e24875. PMID: 21966374.

11. Kim BM, Kim DJ, Kim DI. Stent application for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Neurointervention. 2011; 8. 6(2):53–70. PMID: 22125751.

12. Klisch J, Clajus C, Sychra V, Eger C, Strasilla C, Rosahl S, et al. Coil embolization of anterior circulation aneurysms supported by the Solitaire AB Neurovascular Remodeling Device. Neuroradiology. 2010; 5. 52(5):349–359. PMID: 19644683.

13. Klisch J, Eger C, Sychra V, Strasilla C, Basche S, Weber J. Stent-assisted coil embolization of posterior circulation aneurysms using solitaire ab: preliminary experience. Neurosurgery. 2009; 8. 65(2):258–266. discussion 266PMID: 19625903.

14. Krischek O, Miloslavski E, Fischer S, Shrivastava S, Henkes H. A comparison of functional and physical properties of self-expanding intracranial stents [Neuroform3, Wingspan, Solitaire, Leo+, Enterprise]. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2011; 2. 54(1):21–28. PMID: 21506064.

15. Lavine SD, Meyers PM, Connolly ES, Solomon RS. Spontaneous delayed proximal migration of enterprise stent after staged treatment of wide-necked basilar aneurysm: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2009; 5. 64(5):E1012. discussion E1012. PMID: 19404126.

16. Lee SY, Chae KS, Rho SJ, Choi HK, Park HS, Ghang CG. Clinical and angiographic outcomes of wide-necked aneurysms treated with the solitaire AB stent. J Cerebrovasc Endovasc Neurosurg. 2013; 9. 15(3):158–163. PMID: 24167794.

17. Lubicz B, François O, Levivier M, Brotchi J, Balériaux D. Preliminary experience with the enterprise stent for endovascular treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms: potential advantages and limiting characteristics. Neurosurgery. 2008; 5. 62(5):1063–1069. discussion 1069-70PMID: 18580804.

18. Mocco J, Snyder KV, Albuquerque FC, Bendok BR, Alan SB, Carpenter JS, et al. Treatment of intracranial aneurysms with the Enterprise stent: a multicenter registry. J Neurosurg. 2009; 1. 110(1):35–39. PMID: 18976057.

19. Peluso JP, van Rooij WJ, Sluzewski M, Beute GN. A new self-expandable nitinol stent for the treatment of wide-neck aneurysms: initial clinical experience. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008; 8. 29(7):1405–1408. PMID: 18436611.

Table 1

Baseline data of the 89 aneurysms treated with Solitaire and Enterprise stent assisted coil embolization in 86 patients

Table 2

Periprocedural complications in stent-assisted coiling

| Solitaire | Enterprise | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stent malposition | 0 | 0 | - |

| Delivery/deployment fail | 0 | 0 | - |

| In-stent stenosis/thrombosis | 0 | 0 | - |

| Thromboembolic event | 2 | 1 | 0.293 |

| Coil protrusion into vessel lumen | 7 | 17 | 0.417 |

Table 3

Angiographic results of 89 aneurysms treated with Solitaire and Enterprise stent-assisted coiling

Table 4

Clinical results of 89 aneurysms treated with Solitaire and Enterprise stent-assisted coiling

| mRS | Solitaire | Enterprise | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| At discharge | 0.213 | ||

| 0 | 32 | 51 | |

| 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| Last | 1.0 | ||

| 0 | 32 | 55 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Mean follow-up (months) | 20.5 | 21 | - |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download