Abstract

Intracranial embolization usually arises from the heart, a vertebrobasilar artery, a carotid artery, or the aorta, but rarely from the distal subclavian artery upstream of an embolus. We report on a patient who experienced left shoulder and forearm pain with weak blood pressure and pulse followed by concurrent onset of left hemiplegia. This case is a rare example of multiple cerebral embolic infarctions, which developed as a complication of distal subclavian artery thrombosis possibly associated with protein S deficiency.

Cerebral embolism is an important etiology of stroke in young adults. Emboli most often arise from the heart but may originate from another location within the arterial tree. In a paradoxical embolism, deep vein thrombosis embolizes through an atrial or ventricular septal defect in the heart into the brain.

Hypercoagulable states, such as those associated with protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome are etiologies associated with arterial thrombosis and ischemic stroke in young adults, although their incidence is rare.3) Subclavian artery occlusive disease usually occurs secondary to persistent compression caused by thoracic outlet syndrome and rarely as a result of focal atherosclerosis or thrombosis. Rarely, retrograde flow of emboli from a diseased vessel to the vertebral or carotid arteries can occur, causing an ischemic infarct.5)

Here, we report on an unusual case of distal subclavian artery thrombosis presenting with cerebral embolization in order to create awareness of ischemic stroke caused by distal or possibly proximal subclavian disease.

A 47-year old female presented in our emergency room with a confused mentality, left side weakness, and left forearm pain. She had no relevant medical history; however, upon questioning, she revealed that she had been prescribed medication at another orthopedic clinic for left shoulder pain 2 weeks previously. Swelling and tenderness of the left forearm was noted, and blood pressure was not measurable, and no pulse was detected in the left upper limb. On the right side, blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg with a regular radial pulse of 80 beats per minute. Disorientation with respect to time and place, a slightly lethargic mental status, and left side hemiparesis with hyperreflexia and Babinski's sign were observed during neurologic examination. The routine battery of blood tests, which included electrolyte analysis, complete blood count, thyroid function test, coagulation factors, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, did not indicate any abnormalities, except a decrease in protein S activity (48%) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (51 cm/hr). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography showed acute infarctions in the left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory, right thalamus, right medial temporal lobe, and right superior cerebellar artery territory of the cerebellum with mild stenosis of the right PCA and the carotid portion of the right internal carotid artery, suggestive of an embolic source proximal to the origins of common carotid and vertebral arteries bilaterally. Normal transesophageal echocardiography and 24-hour holter monitoring were performed in order to exclude possible explanations for cerebral thromboembolism from the heart. Brachial computed tomography (CT) angiography showed occlusion of the left axillary and brachial arteries. Based on suspicion of a cerebral thromboembolism originating from the occluded subclavian artery, intravenous infusion of non-fractionated heparin was administered daily at 1000 units/h with careful monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin.

On day 3, the patient complained of aggravated left arm pain; her left hand was found to be cold to the touch and pale in appearance. Emergent thrombectomy was performed, resulting in rapid subsidence of the left arm pain and recovery of the left radial pulse. Pathologic examination of the thrombus revealed that it contained fibrin, blood clots, and arterial tissue, suggesting organizing thrombi. Anti-coagulant therapy with warfarin was continued postoperatively. The patient was discharged with mild left arm weakness and a left side tingling sensation. Repeat testing for protein S activity after 3 months showed a 2-fold decrease in protein S activity (20%), which was also compatible with protein S type I deficiency.

We report on a case of cerebral embolic infarction secondary to subclavian artery occlusion, possibly associated with protein S deficiency.

Protein S is a vitamin K-dependent plasma protein that serves primarily as a cofactor for activated protein C and plays a vital role in regulation of blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Protein S deficiency manifests most commonly as superficial and deep venous thrombosis, but less commonly as arterial thromboses, such as femoral, cerebral, subclavian, and axillary artery thromboses, which have been described.2)4) Our patient had type I protein S deficiency, which results from deficiency of free and bound protein, which may have been the cause of the distal subclavian occlusion, although it is usually caused by thoracic outlet syndrome.

Although subclavian artery thrombosis complicated by cerebral thromboembolism is uncommon, a number of case studies have reported on cerebral embolism from a subclavian artery thrombotic pathology.1) The pathogenesis of infarcts in the vertebrobasilar and carotid distribution is generally believed to be due to propagation or retrograde embolism from a subclavian artery thrombus.

However, distal subclavian artery occlusion, not proximal artery occlusion, as the source of cerebral infarction would still be very uncommon. Therefore, we suggest that an embolism from proximal subclavian artery thrombosis might have propagated to the distal subclavian artery and its retrograde embolism may have been the source of cerebral infarction.

This rare case of multiple cerebral embolic infarction as a complication of distal subclavian artery thrombosis, possibly associated with protein S deficiency, demonstrates the need for palpation of the radial pulse, measurement of brachial blood pressure in both arms, and consideration of an unusual embolic source, such as subclavian artery thrombosis, during evaluation of stroke patients.

We report on a patient with concurrent occlusion of both cerebral and peripheral arteries, which is very rare. We assume that this multiple embolic infarction may possibly result from protein S deficiency. Accurate evaluation of the source of cerebral infarction is very difficult, however, the possibility of retrograde cerebral infarction and coagulopathy should be considered.

References

1. Jusufovic M, Sandset EC, Popperud TH, Solberg S, Ringstad G, Kerty E. An unusual case of the syndrome of cervical rib with subclavian artery thrombosis and cerebellar and cerebral infarctions. BMC Neurol. 2012; 6. 12:48. PMID: 22741548.

2. Morau D, Barthelet Y, Spilmann E, Ryckwaert Y, d'Athis F. [Thrombus of the aortic arch: An unusual pathology in intensive care]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2000; 10. 19(8):603–606. French. PMID: 11098322.

3. Soare AM, Popa C. Deficiencies of proteins C, S and antithrombin and factor V Leiden and the risk of ischemic strokes. J Med Life. 2010; Jul-Sep. 3(3):235–238. PMID: 20945813.

4. Taheri P, Eagel BA, Karamanoukian H, Hoover EL, Logue G. Functional heredity protein S deficiency with arterial thrombosis. Am Surg. 1992; 8. 58(8):496–498. PMID: 1386500.

5. Chen WH, Chen SS, Liu JS. Concurrent cerebral and axillary artery occlusion: A possible source of cerebral embolization from peripheral artery thrombosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2005; 12. 108(1):93–96. PMID: 16311157.

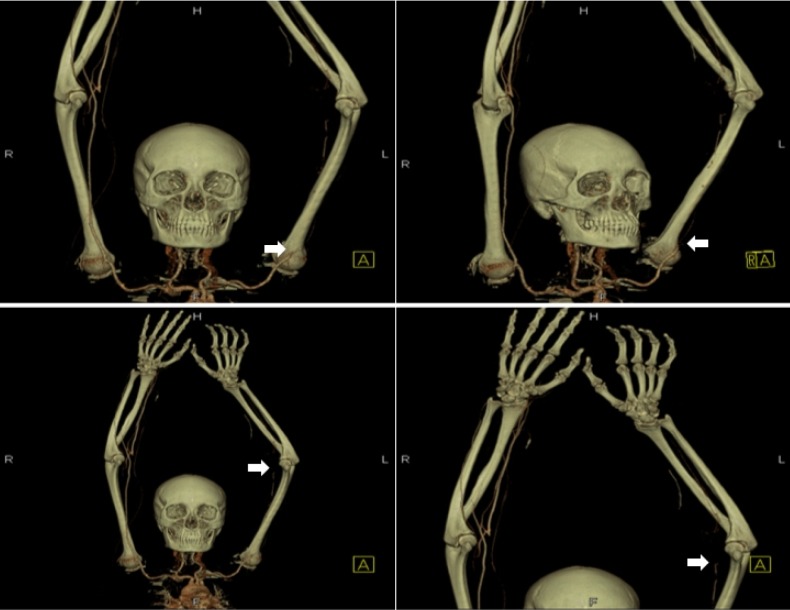

Fig. 1

High signal intensities are observed in the left posterior cerebral artery territory, right thalamus, right medial temporal lobe, and right cerebellum on fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images (white arrow). Mild stenosis is observed at the right posterior cerebral artery and right proximal internal carotid artery, which was probably not the cause of the infarction (white arrowhead).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download