Abstract

We report here on a rare case of a ruptured basilar tip aneurysm that was successfully treated with coil embolization in the bilateral cervical internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusions with abnormal vascular networks from the posterior circulation. A 43-year old man with a familial history of moyamoya disease presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Digital subtraction angiography demonstrated complete occlusion of the bilateral ICAs at the proximal portion and a ruptured aneurysm at the basilar artery bifurcation. Each meningeal artery supplied the anterior cranial base, but most of both hemispheres were supplied with blood from the basilar artery and the posterior cerebral arteries through a large number of collateral vessels to the ICA bifurcation as well as the anterior cerebral and middle cerebral arteries. The perfusion computed tomography (CT) scans with acetazolamide (ACZ) injection revealed no reduction of cerebral blood flow and normal cerebrovascular reactivity to ACZ. An abdominal CT aortogram showed no other extracranial vessel abnormalities. A ruptured basilar tip aneurysm was successfully treated with coil embolization without complications. Endovascular embolization may be a good treatment option with excellent safety for a ruptured basilar tip aneurysm that accompanies proximal ICA occlusion with vulnerable collateral flow.

Bilateral carotid artery occlusion accompanied with basilar tip aneurysm is extremely rare.15) It has been suggested that increased blood flow through the vertebrobasilar system, which is the major source of collateral circulation, intensifies the hemodynamic stress on the arterial walls and this may result in the formation of saccular aneurysms.13) Direct clipping for these aneurysms is difficult and the morbidity is high due to the extensive collateral networks as well as the already compromised cerebral blood flow and high internal blood pressure.2)3)7)14) Thanks to the development of endovascular techniques, the aneurysms that are difficult to reach by craniotomy can now be treated with excellent results.3)4)6) To the best of our knowledge, there have been only seven cases of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar tip aneurysm not being related to moyamoya disease.5)7)8)11)12)17)18) Among them, only three cases were treated with coil embolization.7)12)17) We report here on a rare case of a ruptured basilar tip aneurysm that was successfully treated with coil embolization in the bilateral cervical internal carotid artery (ICA) occlusions with abnormal vascular networks from the posterior circulation.

A 43-year old man with a sudden onset of headache, nausea and vomiting visited the emergency room at our institution. He had a history of hypertension that was being controlled with medication and smoking. His aunt suffered from moyamoya disease, but he had not undergone diagnostic work-up for familial cerebrovascular diseases because he had not experienced neurological deficits such as ischemic attacks, including dysarthria, dizziness and gait disturbances. Mentally alert, the patient had meningismus, experiencing neck stiffness on admission.

A brain computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated diffuse and thick subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the bilateral sylvian fissures, the anterior interhemispheric fissure, the basal cistern and the posterior fossa, including the perimesencephalic region (Fig. 1). Subsequent carotid angiography showed complete occlusion of both ICAs, the so called 'bottle neck appearance' or 'beak shape,' at the level of the carotid bulb without appreciable intracranial filling and there were small collaterals from both external carotid arteries through the middle meningeal arteries to the anterior cranial fossa (Fig. 2). Vertebral artery angiography demonstrated that both hemispheres were seen filling in an antegrade fashion from the upper basilar artery and both posterior cerebral arteries through an extensive network of collateral vessels to the ICA bifurcations. A 6 × 4 mm aneurysm was also observed at the basilar artery bifurcation (Fig. 3). Perfusion CT scans revealed no reduction of cerebral blood flow and normal cerebrovascular reactivity to acetazolamide (Fig. 4). The abdominal CT aortograms did not demonstrate any other extracranial pathological vascular findings, including renal artery stenosis and fibromuscular dysplasia (figures not shown).

The patient underwent endovascular coiling under general anesthesia for the ruptured basilar tip aneurysm. Two Guglielmi electrically detachable platinum coils and two hydrosoft helical coils were successfully deployed into the aneurysm. We tried to deploy a microplex coil at the lower neck portion of the aneurysm, but failed due to the wide neck of the aneurysm. The balloon or stent-assisted technique was not used even though there was a relatively large orifice because of the risk of thromboembolism and obstruction of the parent arteries during the procedure. Eventually, only the dome and waist of the aneurysm were packed completely (Fig. 3C). After embolization, we closely monitored the patient's neurological condition in the intensive care unit. The post-procedural period was uneventful and he was discharged without complications. The first follow-up angiograms 6 months after treatment did not show aneurysm recanalization.

Atherosclerosis and aortic inflammation are known to be the most common causes of bilateral carotid artery occlusion without moyamoya disease.17) Atherosclerosis can occur at the point of ICA bifurcation, leading to chronic and progressive arterial stenosis, whereas aortic inflammation is likely to be involved with the aortic arch and its branches, resulting in bilateral carotid artery occlusion. Generally, an occlusion at the beginning part of the ICA is likely to be caused by atherosclerosis, while the occlusion of the bilateral common carotid artery is likely aortitis.17) According to the study by AbuRahma and Copeland,1) all patients with atherosclerotic bilateral ICA occlusion had a history of cerebral ischemic attack such as transient ischemic attack (TIA), amaurosis fugax, or stroke even though collateral circulation was present, and they all needed surgical interventions such as endarterectomy, carotid-subclavian bypass or medical treatments using warfarin or aspirin.

By contrast, definite cases of moyamoya disease are diagnosed in patients with bilateral stenosis or occlusion that occurs at the terminal portion of the ICA together with an abnormal vascular network at the base of the brain, as is shown by cerebral angiography. The etiology of moyamoya disease is unknown. Thus, moyamoya syndromes that have underlying diseases such as cerebrovascular disease with atherosclerosis, autoimmune disease, meningitis, brain neoplasm, Down's syndrome, neurofibromatosis, head trauma or irradiation to the head, as well as other conditions, should be excluded.9)

Meanwhile, our case showed complete occlusion at the bilateral proximal portion of the internal carotid arteries above the carotid bulbs with abnormal vascular networks from the posterior circulation without basal moyamoya vessels. The patient did not have any underlying diseases such as cerebral infection, trauma and aortic inflammation that may lead to stenosis or occlusion of the ICA. Although he had no past history of TIA, he had two risk factors for atherosclerosis which were hypertension and smoking. No abnormal findings that may imply fibromuscular dysplasia were seen on the vertebral and abdominal angiograms. These findings are not characteristics of moyamoya disease or moyamoya syndrome, but suggest idiopathic or atherosclerotic bilateral carotid artery occlusion.

The basilar tip aneurysm associated with bilateral carotid artery occlusion or moyamoya disease is well known, life-threatening complication that causes SAH. To the best of our knowledge, there have been only seven cases of bilateral carotid artery occlusion with concurrent basilar tip aneurysm without moyamoya disease in the literature.5)7)8)11)12)17)18) The causes of carotid artery occlusion included aortic inflammation in two cases and atherosclerosis in five cases.5)7)8)11)12)17)18) Of them, 5 cases had SAH.8)11)12)17)18) It has been suggested that increased blood flow through the vertebrobasilar system, which is the major source of collateral circulation in bilateral carotid artery occlusion, intensifies the hemodynamic stress on the arterial walls and this may result in the formation of saccular aneurysms.13) Although the formation of anastomosis from the external carotid artery may alleviate the hemodynamic burden on the posterior circulation, the effect is limited and local blood pressure still rises which leads to the risk of basilar artery aneurysms.17) Conservative management for these aneurysms can lead to dismal results,11)18) therefore quick, aggressive treatments should be considered. Such aneurysms can be treated with direct clipping. However, direct clipping is difficult and dangerous due to extensive collateral channels,2)14) stiffness of the carotid artery,10)16) and high internal blood pressure.7) Moreover, the fact that the basilar artery is the sole source of blood for most of the brain precludes prolonged temporary clipping to aid in safe dissection around the aneurysm.13) Thus, these aneurysms have been recently treated with endovascular procedures using soft platinum coils. There have been several reports have showing excellent results of endovascular embolization for the basilar tip aneurysms in patients with moyamoya disease and bilateral ICA occlusion.4)6)7)10)12)17) Of course, if increased blood burden through the vertebrobasilar system is not alleviated, the aneurysm will probably regrow. Thus, in our case, regular follow-up angiograms are essential and additional embolization with extra-intracranial revascularization may be needed even though there was no perfusion defect seen on the perfusion CT scans.

Proximal bilateral ICA occlusion is rare but often shows similar clinical features with moyamoya disease such as abnormal collateral vascular networks from posterior circulation and accompanying saccular aneurysms. Differential diagnosis between idiopathic and atherosclerotic occlusion may be needed for further cardiovascular work-up. The basilar tip aneurysm associated with proximal bilateral ICA occlusion is more rare and dangerous, but curable disease. Endovascular embolization for such aneurysms is safe and useful even without the assistance of balloon or stent.

Figures and Tables

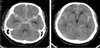

Fig. 1

Brain computed tomography scans demonstrate a diffuse and thick subarachnoid hemorrhage in the bilateral sylvian fissures, the anterior interhemispheric fissure, the basal cistern and the posterior fossa, including the perimesencephalic region.

Fig. 2

Right (A) and left (B) carotid digital subtraction angiography scans show complete occlusion of both internal carotid arteries at the level of the carotid bulb without appreciable intracranial filling and small collaterals from both middle meningeal arteries to the anterior cranial fossa.

Fig. 3

A: A vertebral digital subtraction angiography (DSA) demonstrates that both hemispheres are filling in an antegrade fashion from the upper basilar artery and both posterior cerebral arteries through an extensive network of collateral vessels, which mimicked moyamoya vessels, to the internal carotid artery bifurcations. B: A 6 × 4 mm aneurysm is also observed at the basilar artery bifurcation. C: The postembolization DSA shows almost complete obliteration of the aneurysm and patency of the arteries surrounding it.

Fig. 4

Pre-acetazolamide (ACZ) perfusion computed tomography (CT) scans show no abnormalities of the cerebral blood flow (CBF) (A), the cerebral blood volume (CBV) (B) and the mean transit time (MTT) (C). Post-ACZ perfusion CT scans for the CBF (D), CBV (E) and MTT (F) show normal cerebrovascular reactivity to ACZ.

References

1. AbuRahma AF, Copeland SE. Bilateral internal carotid artery occlusion: natural history and surgical alternatives. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998. 12. 6(6):579–583.

2. Adams HP Jr, Kassell NF, Wisoff HS, Drake CG. Intracranial saccular aneurysm and moyamoya disease. Stroke. 1979. 03. 10(2):174–179.

3. Arita K, Kurisu K, Ohba S, Shibukawa M, Kiura H, Sakamoto S, et al. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease. Neuroradiology. 2003. 07. 45(7):441–444.

4. Irie K, Kawanishi M, Nagao S. Endovascular treatment of basilar tip aneurysm associated with moyamoya disease--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2000. 10. 40(10):515–518.

5. Ishibashi A, Yokokura Y, Kojima K, Abe T. Acute obstructive hydrocephalus due to an unruptured basilar bifurcation aneurysm associated with bilateral internal carotid occlusion--a case report. Kurume Med J. 1993. 40(1):21–25.

6. Kagawa K, Ezura M, Shirane R, Takahashi A, Yoshimoto T. Intraaneurysmal embolization of an unruptured basilar tip aneurysm associated with moyamoya disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2001. 09. 8(5):462–464.

7. Konishi Y, Sato E, Shiokawa Y, Yazaki H, Hara M, Saito I. A combined surgical and endovascular treatment for a case with five vertebro-basilar aneurysms and bilateral internal carotid artery occlusions. Surg Neurol. 1998. 10. 50(4):363–366.

8. Kumagai Y, Sugiyama H, Nawata H, Izeki H, Baba M, Ohta S, et al. [Two cases of pulseless disease with cerebral aneurysm(author's transl)]. No Shinkei Geka. 1981. 04. 9(5):611–615. Japanese.

9. Kuroda S, Houkin K. Moyamoya disease: current concepts and future perspectives. Lancet Neurol. 2008. 11. 7(11):1056–1066.

10. Massoud TF, Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Duckwiler GR. Saccular aneurysms in moyamoya disease: endovascular treatment using electrically detachable coils. Surg Neurol. 1994. 06. 41(6):462–467.

11. Masuzawa T, Shimabukuro H, Sato F, Furuse M, Fukushima K. The development of intracranial aneurysms associated with pulseless disease. Surg Neurol. 1982. 02. 17(2):132–136.

12. Meguro T, Tanabe T, Muraoka K, Terada K, Hirotsune N, Nishino S. Endovascular treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with bilateral common carotid artery occlusion. Interv Neuroradiol. 2008. 12. 14(4):447–452.

13. Muizelaar JP. Early operation of ruptured basilar artery aneurysm associated with bilateral carotid occlusion (moyamoya disease). Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1988. 06. 90(4):349–355.

14. Nagamine Y, Takahashi S, Sonobe M. Multiple intracranial aneurysms associated with moyamoya disease. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1981. 05. 54(5):673–676.

15. Shibuya T, Hayashi N. A case of posterior cerebral artery aneurysm associated with idiopathic bilateral internal carotid artery occlusion: case report. Surg Neurol. 1999. 12. 52(6):617–622.

16. Suzuki J, Takaku A. Cerebrovascular "moyamoya" disease. Disease showing abnormal net-like vessels in base of brain. Arch Neurol. 1969. 03. 20(3):288–299.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download