Abstract

Distal thrombosed aneurysm of the superior cerebellar artery (SCA) is extremely rare and is often associated with cerebellar infarction or subarachnoid hemorrhage. We report herein on a case involving a patient with a ruptured thrombosed distal SCA aneurysm which was treated successfully through the endovascular approach.

The incidence of aneurysms from the distal superior cerebellar artery (SCA) is only 0.2% of all intracranial aneurysms.1) Several surgical procedures, including parent artery occlusion, clipping of the aneurysmal neck, trapping of the bleeding site, and wrapping of the aneurysm have been proven effective in preventing rupture of a distal SCA aneurysm.2) However, due to difficulty conserving all of the perforating artery and maintaining the patency of the parent artery during the surgical procedure, satisfactory surgical occlusion or trapping cannot always be performed with distal SCA aneurysms. Therefore, surgical, endovascular, and combined approaches, based on their characteristics, such as size or location, have been widely used in treatment of these aneurysms.3)7)8)9)10) On the other hand, to the best of our knowledge, little information is available on endovascular approaches in treatment of distal SCA aneurysms.2)3)5)6)15) We report herein on a case involving a patient with a ruptured thrombosed distal SCA aneurysm which was treated successfully through the endovascular approach.

A 77-year-old male patient was admitted with complaints of dizziness and headache of two days' duration. The neurological examination showed agitation and neck stiffness. Findings on computed tomography (CT) showed a round thrombosed aneurysm of right distal SCA measuring 18 × 18 mm and a subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (Fig. 1A). Brain diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an acute right cerebellar infarction (Fig. 1B). Conventional angiographic finding indicated an aneurysmal dilatation of the right distal SCA. The aneurysm measured approximately 22 mm in length and showed partial thrombosis (Fig. 2A, B); therefore, we performed parent artery occlusion with endovascular coil embolization. A microcatheter was inserted into the right distal SCA, and parent artery occlusion with 12 detachable coils was performed. No residual aneurysmal sac was evident after the procedure. Successful occlusion of the aneurysm and parent artery was demonstrated on a 10 minute delay angiogram, and all proximal segments of the right SCA were preserved (Fig. 3A, B, C). After the procedure, the patient's headache and dizziness tended to show improvement and the patient exhibited a better overall condition. The follow-up MRI after one week showed a multifocal acute infarction on the right cerebellar hemisphere (Fig. 4). Despite mild dizziness, the patient left the hospital without definite neurological deficit. No bleeding was observed upon follow-up at four months.

Distal SCA aneurysms are uncommon, constituting 0.2% of all intracranial aneurysms.4) The SCA usually supplies the entire superior surface of the cerebellar hemisphere, the superior vermis, dentate nucleus, most of the cerebellar white matter, and parts of the midbrain. Clinical manifestations of SCA occlusion range from clinical silence to infarction of the cerebellum and brain stem. Common symptoms include vertigo, nausea, vomiting and loss of balance, and headache; additional symptoms include ipsilateral Horner syndrome, ipsilateral intension tremor, nystagmus, contralateral hearing disturbance, contralateral loss of pain and temperature, and loss of emotional expression.2)

Due to the ample collateral supply of the distal posterior cerebral artery, distal SCA aneurysms are conformable to deconstructive surgical treatment.5) SCA arises near the distal end of the basilar artery and divides into the rostral and caudal trunk. The main artery and the rostral and caudal trunks give rise to perforating, precerebellar, and cortical arteries. The cortical branches split into the vermian and hemispheric groups. Hemispheric branches supply the tentorial surface lateral to the vermis. In general, there are three hemispheric branches, and each branch supplies approximately one third of the tentorial surface. However, the territory is not always limited; for example, two branches supply hemispheric areas together. The vermian artery is a branch from the rostral trunk. The connection between vermian branches is frequent, therefore, if one side of the vermian branch is hypoplastic, the contralateral side of the vermian branch supplies that area. There is a marginal branch from the proximal SCA trunk in approximately half, and it supplies the part of the petrosal surface adjacent to the tentorial surface. Anastomosis between the marginal artery and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) is common. Like this, there are many collateral circulations between SCAs and other cerebellar arteries, therefore, many patients have recovered and survived from major cerebellar artery occlusions.

Serious neurological deficit or extensive infarction after parent artery trapping of distal SCA aneurysms has been reported in the literature.4) However, Atalay et al. reported several cases of distal SCA aneurysm in which patients were treated with trapping of the parent artery without serious neurological deficits.6) Chaloupka et al. also reported two cases of distal SCA aneurysm in which patients were treated with endovascular parent artery occlusion without definite neurologic deficit.3) This presumably reflects the rich anastomoses of the SCAs and other cerebellar arteries and the variations in arterial distribution over the cerebellum.6)

Surgical, endovascular, or combined approaches have been used in treatment of SCA aneurysms.3)7)8)9)10) Therapeutic strategies are dependent on several factors, including the relationship of the aneurysm to the parent artery, the size of aneurysm, and the location. Most distal aneurysms require occlusion of the parent artery.2) Traditional treatment with surgical or endovascular embolization usually spares the parent vessel, therefore, treating distal intracranial aneurysms using these techniques was difficult.11) Until now, surgical treatment has been the primary treatment modality for parent artery occlusion of distal SCA aneurysms.3) Although surgical treatment by experienced surgeons is known to yield favorable results, approach to the distal SCA may be challenging, taking a destructive subtemporal transtentorial, occipital transtentorial or intratentorial supracerebellar approach.12)13) Endovascular approach for parent artery occlusion is simple to perform, technically easy, and equally useful as a surgical treatment, without the risk of craniotomy and long time under general anesthesia. Additionally, the endovascular approach has the benefit of not directly injuring the brainstem or the lower cranial nerves.14)

Similar to previous reports, in this case, endovascular parent artery occlusion resulted in effective separation of the aneurysm from the bloodstream and no significant cerebellar infarction occurred. However, because large thrombosed aneurysms tend to recur after coil embolization, we believe that, in this case, long-term follow-up is still necessary.

Figures and Tables

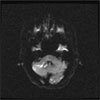

Fig. 1

Brain computed tomography (A) shows subarachnoid hemorrhage and a round, hyperdense lesion in the right ambient cistern (suggestive of a thrombosed aneurysm). Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (B) shows an acute infarction in the right cerebellum.

Fig. 2

A left vertebral angiogram shows a thrombosed distal SCA aneurysm. Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) view.

References

1. Matricali B, Seminara P. Aneurysm arising from the medial branch of the superior cerebellar artery. Neurosurgery. 1986. 03. 18(3):350–352.

3. Chaloupka JC, Putman CM, Awad IA. Endovascular therapeutic approach to peripheral aneurysms of the superior cerebellar artery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996. 08. 17(7):1338–1342.

4. Ohta H, Sakai N, Nagata I, Sakai H, Shindo A, Kikuchi H. Spontaneous total thrombosis of distal superior cerebellar artery aneurysm. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001. 08. 143(8):837–842. discussion 842-3.

5. Arat A, Islak C, Saatci I, Kocer N, Cekirge S. Endovascular parent artery occlusion in large-giant or fusiform distal posterior cerebral artery aneurysms. Neuroradiology. 2002. 08. 44(8):700–705.

6. Atalay B, Altinors N, Yilmaz C, Caner H, Ozger O. Fusiform aneurysm of the superior cerebellar artery: short review article. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007. 03. 149(3):291–294. discussion 294.

7. Danet M, Raymond J, Roy D. Distal superior cerebellar artery aneurysm presenting with cerebellar infarction: report of two cases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001. 04. 22(4):717–720.

8. Gotoh H, Takahashi T, Shimizu H, Ezura M, Tominaga T. Dissection of the superior cerebellar artery: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2004. 02. 11(2):196–199.

9. Haw C, Willinsky R, Agid R, TerBrugge K. The endovascular management of superior cerebellar artery aneurysms. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004. 02. 31(1):53–57.

10. Zhang YJ, Barrow DL, Cawley CM, Dion JE. Neurosurgical management of intracranial aneurysms previously treated with endovascular therapy. Neurosurgery. 2003. 02. 52(2):283–293. discussion 293-5.

11. Eid Lidt G. [Endovascular treatment: peripheral vascular disease]. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2003. Apr-Jun. 73:Suppl 1. S34–S40. Spanish.

12. Kubota S, Ohmori S, Tatara N, Nagashima C. [A ruptured peripheral, superior cerebellar artery aneurysm: a case report and a review of the literature as to surgical approaches]. No Shinkei Geka. 1994. 03. 22(3):279–283. Japanese.

13. Gacs G, Vinuela F, Fox AJ, Drake CG. Peripheral aneurysms of the cerebellar arteries. Review of 16 cases. J Neurosurg. 1983. 01. 58(1):63–68.

14. Jeon SG, Kwon DH, Ahn JS, Kwun BD, Choi CG, Jin SC. Detachable coil embolization for saccular posterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysms. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009. 09. 46(3):221–225.

15. Lubicz B, Leclerc X, Gauvrit JY, Lejeune JP, Pruvo JP. Endovascular treatment of peripheral cerebellar artery aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003. Jun-Jul. 24(6):1208–1213.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download