Abstract

Purpose

This study was performed to investigate the intra- and inter-observer variability in linear measurements with axial images obtained by PreXion (PreXion Inc., San Mateo, USA) and i-CAT (Imaging Sciences International, Xoran Technologies Inc., Hatfield, USA) CBCT scanners, with different voxel sizes.

Materials and Methods

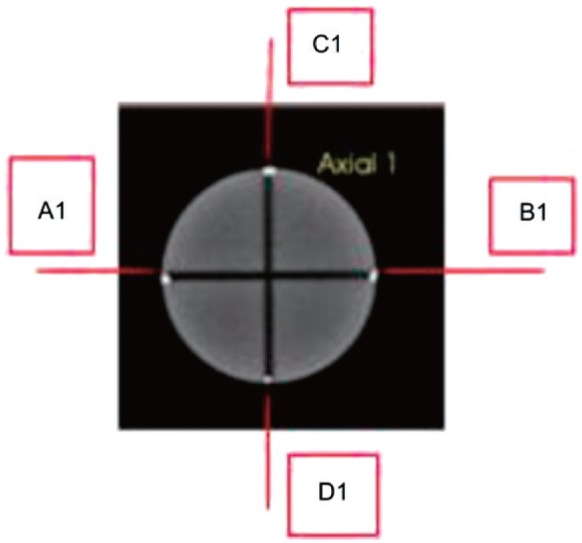

A cylindrical object made from nylon with radiopaque markers (phantom) was scanned by i-CAT and PreXion 3D devices. For each axial image, measurements were taken twice in the horizontal (distance A-B) and vertical (distance C-D) directions, randomly, with a one-week interval between measurements, by four oral radiologists with five years or more experience in the use of these measuring tools.

Results

All of the obtained linear measurements had lower values than those of the phantom. The statistical analysis showed high intra- and inter-observer reliability (p=0.297). Compared to the real measurements, the measurements obtained using the i-CAT device and PreXion tomography, on average, revealed absolute errors ranging from 0.22 to 0.59 mm and from 0.23 to 0.63 mm, respectively.

Linear measurements are mainly used to assess the thickness and height of the alveolar crest as part of the preoperative evaluation for implant treatment, to measure the distance between anatomical landmarks in orthodontics and orthognathic surgery, and to estimate the size of pathological jaw lesions. The accuracy and reliability of linear measurements in cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images has been established in several published scientific studies,1234567891011 including studies where they have been obtained from CBCT-derived models.212

Ostensibly, in imaging of the oral and maxillofacial complex, spatial resolution is an important parameter of image quality that appears to be of special interest for dental applications. As available spatial resolution also determines the accuracy with which anatomic detail can be measured, it also affects important procedures, such as the planning of dental implants or cephalometric analysis.

The spatial resolution of an image is directly influenced by the voxel size, which is the smallest unit in CBCT images.13141516 To improve spatial resolution, the voxel size must be reduced,17 and the CBCT images must be measured accurately. However, spatial resolution is affected by multiple technical factors that make it difficult to predict from simple clues or to estimate from technical parameters.13 The presence of an increasing number of CBCT units on the market presents a need to understand and select from the various technical parameters.

The impact of variation in voxel size on CBCT-based diagnostics has been discussed.17 As the PreXion CBCT device has a small voxel size and few studies1819 have evaluated it, this study investigated the intraobserver and interobserver variability in linear measurements with axial images obtained by PreXion (PreXion Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) and i-CAT (Imaging Sciences International, Xoran Technologies Inc., Hatfield, PA, USA), with different voxel sizes.

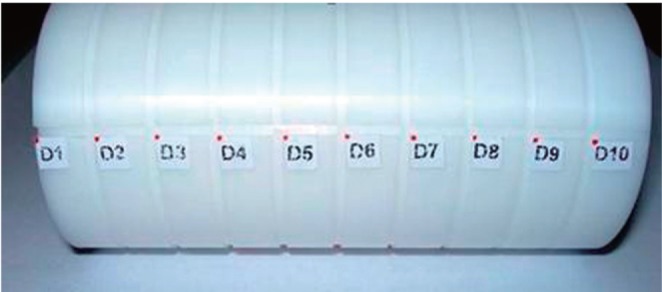

The phantom used for this study was based on that of a previous study.6 It was made from nylon, a slightly radiopaque material with a low thermal expansion coefficient, in a cylindrical shape (5 cm in diameter and 10 cm in length). It had 4 channels, each 1 mm in depth, arranged 90° apart on the longitudinal axis of the cylinder, and 10 channels, each with a depth of 1 mm, arranged transversely 10 mm apart.

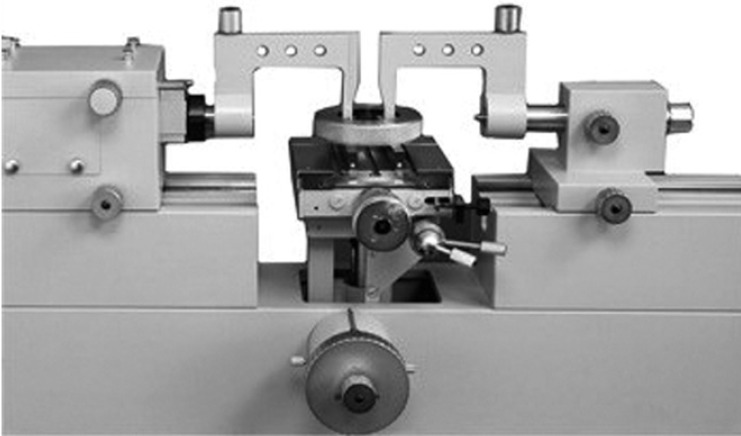

The dimensional calibration of the phantom was performed using the PML-0024 measuring procedure with a universal measuring machine (Mitutoyo Sul Americana Ltda, Suzano, São Paulo, Brazil) (Fig. 1), at room temperature (20.0±0.5℃). The diameter of the phantom (the cylinder) was verified 4 times in 10 sections, as identified in the standard, in 2 coordinates, A/B and C/D, generating a report containing the resulting averages. The measurement uncertainty was U=0.01, based on a combined standard uncertainty, multiplied by a coverage factor of k=2.3 for a confidence level of approximately 95%. The average values obtained by dimensional calibration of the phantom were considered the real measurements (the gold standard).

To identify the “sections” of the phantom selected for the experiment, zinc oxide and eugenol dotted portions were added at each channel intersection (Fig. 2), and the letters A, B, C, and D and the numbers 1 through 10 were applied for identification (Fig. 3).6

After obtaining the real measurements, the phantom was scanned in the i-CAT device, following an image acquisition protocol of a 6-cm×16-cm field of view (FOV), 20 seconds, and a 0.2-mm voxel size. In the PreXion device, the phantom was scanned following an image acquisition protocol of 5-cm×5-cm FOV, 19 seconds, and a 0.1-mm voxel size. Thereafter, multiplanar reformatting was performed, thereby obtaining axial sections with a thickness of 1.0 mm. The data were saved in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine format using Prexion3DViewer software version 2.4.1.20 (PreXion Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) to measure the diameter of each axial image.

The diameter of the phantom was measured in sections, using 2 coordinates (An/Bn and Cn/Dn) with numbers from 2 to 7, in the depth of the channel, that is, between the “points” marked with zinc oxide and eugenol. This measurement was performed using a software tool. For each axial image, measurements were made in either horizontal direction (the A-B distance) and in either vertical direction (the C-D distance), twice, with a 1-week interval, by 4 examiners (4 oral radiologists) with 5 years or more experience in the use of these measuring tools. All post-processing procedures were carried out using the same software, Prexion3DViewer version 2.4.1.20, and the images were visualized on a 24-inch LG E 2241 LCD monitor with a matrix resolution of 1920×1080. The values of the 2 repetitions for each coordinate were entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA), separated by examiner, by scanner, by section, and by distance (A-B and C-D).

Statistical analysis was applied to the collected data using SPSS Statistics for Windows, (version 20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) calculations were used to verify intraobserver and interobserver agreement and to compare the accuracy (reproducibility) of the i-CAT and PreXion CBCT with the real measurements (the gold standard). The linear measurements (mm) were subjected to descriptive analysis to present the absolute and relative errors (in %) of the measurements performed on the acquisitions made with both CBCT machines in relation to the gold standard. The Student t-test was used to compare the scans to each other regarding the linear measurements. The significance level used for all tests was 5% (α=.05).

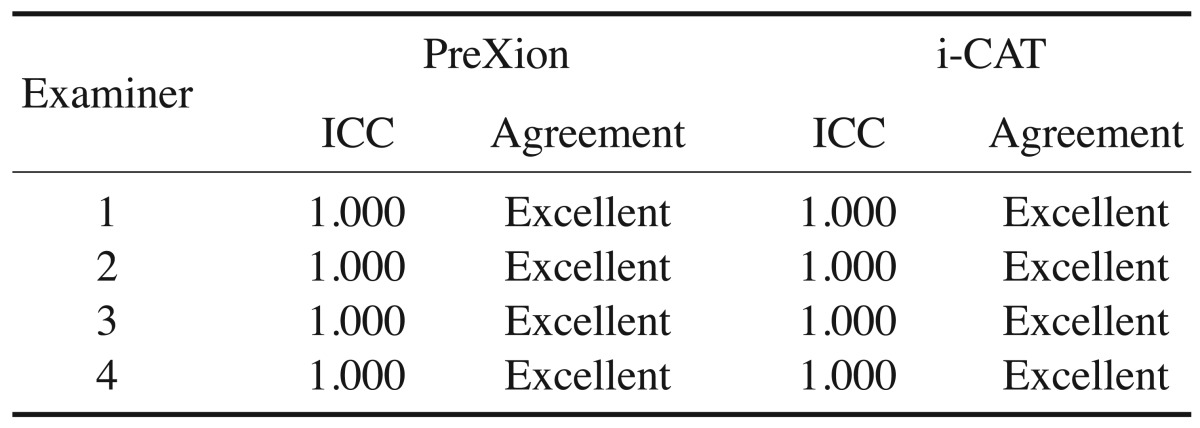

The ICC calculations revealed that the intra-observer agreement was excellent (ICC=1.000) when comparing the linear measurements performed at the 2 image evaluation stages, for both those obtained with the i-CAT scanner and for those with the PreXion scanner, for the 4 examiners.

The inter-observer agreement when using the i-CAT or PreXion scanner was excellent (ICC=1.000) in all comparisons between the 4 examiners.

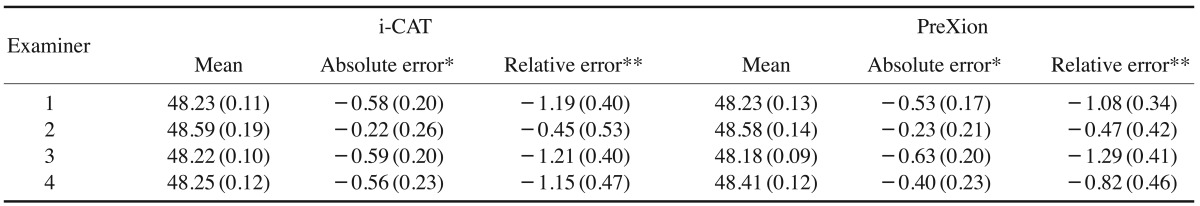

Table 1 presents the descriptive analysis, in terms of the mean, standard deviation, and absolute and relative errors (%) of the linear measurements (mm) of the cylindrical object (the phantom) obtained with the use of the i-CAT and PreXion computed tomography scanners.

The measurements obtained in tomographic acquisition using the i-CAT device, on average, showed absolute errors ranging from 0.22 mm to 0.59 mm when compared with the real measurements, which were underestimated. The linear measurements taken from acquisitions made with the PreXion scanner also underestimated the linear dimensions, with absolute errors ranging from 0.23 mm to 0.63 mm.

For the ICCs, it was found that with both scanners (i-CAT and PreXion), the accuracy of the linear measurements compared to the real measurements (the gold standard) was excellent (Table 2). When comparing the CBCTs to each other, no significant difference was found (p=.297).

The use of CBCT technology to evaluate structures of the oral and maxillofacial complex increases the accuracy and reliability of the measurements, because of its ability to manipulate the resulting digital data volumes across 3 different views (sagittal, coronal, and axial) and to selectively contrast, emphasize, and reduce the images to view certain anatomical structures.20 This study evaluated whether voxel size affected the intra-observer and inter-observer variability of the linear measurements obtained from the axial images of 2 CBCT devices.

In our study, the intra-observer and inter-observer agreement values, when using the i-CAT or PreXion scanner, were excellent in all comparisons of the 4 examiners (ICC=1.000), as shown in Tables 1 and 2. High interobserver and intraobserver CBCT reliability was reported by Moshfeghi et al.11 and Kamburoğlu et al.7, while in the study by Nikneshan et al.1, reproducibility for all orientations was greater than 0.9.

In a comparison of the different devices, it was found that there was no significant difference (p=.297) despite the difference between the voxel sizes (0.1 mm for the PreXion and 0.2 mm for the i-CAT). Lukat et al.21 have already reported this result and emphasized that high spatial resolution allows for the thorough detection of subtle structures, such as small changes in the cortical or the buccal bone of the temporomandibular joint.3522

Measurements for preoperative implant site assessment taken from CBCT images should be considered accurate when the error was less than 1 mm.415 Owing to the mechanical construction of CBCT machines, which require a relatively slow trajectory of the source image detector unit around the patient's head, even slight patient movement seems almost inevitable. Given the small voxel sizes applied in the machines, a slight movement of more than 1 voxel will lead to errors in reconstruction.13 Therefore, during clinical application, one should not expect greater accuracy than half a millimeter at best. If in doubt, users should avoid sub-millimeter accuracy and preferably add some margin of error to their planning.

Table 1 shows the values of the measurements obtained using the i-CAT apparatus, on average, which produced absolute errors ranging from 0.22 mm to 0.59 mm compared with the actual measurements, which were underestimated. As for the PreXion device, the measurements were lower than the actual linear dimensions, with absolute error varying between 0.23 mm and 0.63 mm, in accordance with the results of the study from Waltrick et al.14 that reported mean absolute errors of 0.23±0.2 mm using voxel sizes of 0.2 mm, 0.3 mm, and 0.4 mm.

Using ICCs, it was found that the accuracy of the linear measurements versus the gold standard was excellent for both devices (Table 2), although all linear measurements were underestimated by the examiners, corroborating the results of several studies described in the literature.4679101123 In addition, thin bony structures of less than 0.5 mm in size are not relevant in actual clinical practice, which compromises the reliability of the CBCT images310 once areas without bone are considered. This lack of precision leading to values that underestimate the real measurements may be explained by the partial volume effect.24252627 This artifact results when the voxel reproduces an average value between the true values for 2 objects (e.g. tooth and surrounding air) with distinctive density. Therefore, the interpretation becomes questionable.

One of the most common voxel sizes used in orthodontics is 0.3 mm, although it should be used with caution if the goal is to assess small variations in bone thickness. A smaller voxel size would be more appropriate for these studies when it is possible to minimize the influence of partial volume averaging.2728 Reducing the voxel size results in an increased dose of radiation, which has an effect on the biological risk of X-ray exposure, especially in children.28

In the present study, known and calibrated measurements from a geometric phantom from a previous study were used as the gold standard.6 This provides the advantage of high reproducibility without exposure of living tissue. However, it was not possible to reproduce some physical phenomena that occur in anthropometric and clinical trials, such as attenuation of the radiation beam, dispersed radiation, and noise.

High-resolution protocols provide images rich in detail and are associated with high levels of X-radiation; thus, further clinical studies are necessary. In conclusion, the intraobserver and interobserver variability and the accuracy of linear measurements in axial CBCT images were excellent. There were no differences in terms of the performance of the CBCT scanners.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mr. Carlos Kazuo Suetake for providing technical information and Mr. Abmael Henrique dos Santos and Mr. Bruno S. J da Silva for assistance with the phantom calibration at Mitutoyo Sul American Ltda.

References

1. Nikneshan S, Aval SH, Bakhshalian N, Shahab S, Mohammadpour M, Sarikhani S. Accuracy of linear measurement using cone-beam computed tomography at different reconstruction angles. Imaging Sci Dent. 2014; 44:257–262. PMID: 25473632.

2. Wikner J, Hanken H, Eulenburg C, Heiland M, Gröbe A, Assaf AT, et al. Linear accuracy and reliability of volume data sets acquired by two CBCT-devices and an MSCT using virtual models: a comparative in-vitro study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016; 74:51–59. PMID: 25936361.

3. Leung CC, Palomo L, Griffith R, Hans MG. Accuracy and reliability of cone-beam computed tomography for measuring alveolar bone height and detecting bony dehiscences and fenestrations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010; 137(4 Suppl):S109–S119. PMID: 20381751.

4. Ganguly R, Ruprecht A, Vincent S, Hellstein J, Timmons S, Qian F. Accuracy of linear measurement in the Galileos cone beam computed tomography under simulated clinical conditions. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011; 40:299–305. PMID: 21697155.

5. Patcas R, Markic G, Müller L, Ullrich O, Peltomäki T, Kellenberger CJ, et al. Accuracy of linear intraoral measurements using cone beam CT and multidetector CT: a tale of two CTs. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012; 41:637–644. PMID: 22554987.

6. Panzarella FK, Junqueira JL, Oliveira LB, de Araújo NS, Costa C. Accuracy assessment of the axial images obtained from cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2011; 40:369–378. PMID: 21831977.

7. Kamburoğlu K, Kolsuz E, Kurt H, Kiliç C, Özen T, Paksoy CS. Accuracy of CBCT measurements of a human skull. J Digit Imaging. 2011; 24:787–793. PMID: 20857166.

8. Sabban H, Mahdian M, Dhingra A, Lurie AG, Tadinada A. Evaluation of linear measurements of implant sites based on head orientation during acquisition: an ex vivo study using cone-beam computed tomography. Imaging Sci Dent. 2015; 45:73–80. PMID: 26125001.

9. Sheikhi M, Dakhil-Alian M, Bahreinian Z. Accuracy and reliability of linear measurements using tangential projection and cone beam computed tomography. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2015; 12:271–277. PMID: 26005469.

10. Thönissen P, Ermer MA, Schmelzeisen R, Gutwald R, Metzger MC, Bittermann G. Sensitivity and specificity of cone beam computed tomography in thin bony structures in maxillofacial surgery - A clinical trial. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015; 43:1284–1288. PMID: 26116971.

11. Moshfeghi M, Tavakoli MA, Hosseini ET, Hosseini AT, Hosseini IT. Analysis of linear measurement accuracy obtained by cone beam computed tomography (CBCT-NewTom VG). Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2012; 9(Suppl 1):S57–S62. PMID: 23814563.

12. Maroua AL, Ajaj M, Hajeer MY. The accuracy and reproducibility of linear measurements made on CBCT-derived digital models. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016; 17:294–299. PMID: 27340163.

13. Brüllmann D, Schulze RK. Spatial resolution in CBCT machines for dental/maxillofacial applications - what do we know today? Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015; 44:20140204. PMID: 25168812.

14. Waltrick KB, Nunes de Abreu Junior MJ, Corrêa M, Zastrow MD, Dutra VD. Accuracy of linear measurements and visibility of the mandibular canal of cone-beam computed tomography images with different voxel sizes: an in vitro study. J Periodontol. 2013; 84:68–77. PMID: 22390549.

15. Torres MG, Campos PS, Segundo NP, Navarro M, Crusoé-Rebello I. Accuracy of linear measurements in cone beam computed tomography with different voxel sizes. Implant Dent. 2012; 21:150–155. PMID: 22382754.

16. Watanabe H, Honda E, Tetsumura A, Kurabayashi T. A comparative study for spatial resolution and subjective image characteristics of a multi-slice CT and a cone-beam CT for dental use. Eur J Radiol. 2011; 77:397–402. PMID: 19819091.

17. Spin-Neto R, Gotfredsen E, Wenzel A. Impact of voxel size variation on CBCT-based diagnostic outcome in dentistry: a systematic review. J Digit Imaging. 2013; 26:813–820. PMID: 23254628.

18. Menezes RF, Araújo NC, Santa Rosa JM, Carneiro VS, Santos Neto AP, Costa V, et al. Detection of vertical root fractures in endodontically treated teeth in the absence and in the presence of metal post by cone-beam computed tomography. BMC Oral Health. 2016; 16:48. PMID: 27075880.

19. Khoury HJ, Andrade ME, Araujo MW, Brasileiro IV, Kramer R, Huda A. Dosimetric study of mandible examinations performed with three cone-beam computed tomography scanners. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2015; 165:162–165. PMID: 25897144.

20. Dalmau E, Zamora N, Tarazona B, Gandia JL, Paredes V. A comparative study of the pharyngeal airway space, measured with cone beam computed tomography, between patients with different craniofacial morphologies. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015; 43:1438–1446. PMID: 26189145.

21. Lukat TD, Perschbacher SE, Pharoah MJ, Lam EW. The effects of voxel size on cone beam computed tomography images of the temporomandibular joints. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015; 119:229–237. PMID: 25577416.

22. Liedke GS, Spin-Neto R, da Silveira HE, Schropp L, Stavropoulos A, Wenzel A. Factors affecting the possibility to detect buccal bone condition around dental implants using cone beam computed tomography. Clin Oral Implants Res. (in press).

23. Shokri A, Khajeh S. In vitro comparison of the effect of different slice thicknesses on the accuracy of linear measurements on cone beam computed tomography images in implant sites. J Craniofac Surg. 2015; 26:157–160. PMID: 25569395.

24. Glover GH, Pelc NJ. Nonlinear partial volume artifacts in x-ray computed tomography. Med Phys. 1980; 7:238–248. PMID: 7393149.

25. Baumgaertel S, Palomo JM, Palomo L, Hans MG. Reliability and accuracy of cone-beam computed tomography dental measurements. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 136:19–28. PMID: 19577143.

26. Sun Z, Smith T, Kortam S, Kim DG, Tee BC, Fields H. Effect of bone thickness on alveolar bone-height measurements from cone-beam computed tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011; 139:e117–e127. PMID: 21300222.

27. Maret D, Telmon N, Peters OA, Lepage B, Treil J, Inglèse JM, et al. Effect of voxel size on the accuracy of 3D reconstructions with cone beam CT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012; 41:649–655. PMID: 23166362.

28. Ganguly R, Ramesh A, Pagni S. The accuracy of linear measurements of maxillary and mandibular edentulous sites in cone-beam computed tomography images with different fields of view and voxel sizes under simulated clinical conditions. Imaging Sci Dent. 2016; 46:93–101. PMID: 27358816.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download