Introduction

A bifid mandibular canal is an anatomical variation of the mandibular canal, implying that the mandibular canal is divided into two branches. Each separated canal might contain a neurovascular bundle that can be observed in different forms.

1

The mandibular canal derives from three individual nerve branches with different origins according to the developmental stage of hemimandible.

2 As the fusion of these nerve branches progresses, intraosseous membranous ossification begins and spreads around the nerve path. The development of the mandibular canal can explain the occurrence of a bifid mandibular canal in some patients, as a result of the incomplete fusion of these nerves.

3

Previous studies investigated the incidence of bifid mandibular canals using panoramic radiography and conebeam computed tomography (CBCT).

1,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11 The incidence of bifid mandibular canals has been reported to be in the range of 0.08-0.95% in studies using panoramic radiographs.

1,

3,

4,

5,

6 On the other hand, in studies using CBCT, the incidence of bifid mandibular canals has been reported to be in the range of 15.6-64.8%.

7,

8,

9,

10,

11 Some researchers have tried to classify the patterns of bifid mandibular canals according to their configuration. While Nortje et al

4 and Langlais et al

1 have used panoramic radiography to classify bifid mandibular canals, Naitoh et al

7 have used CBCT imaging. The discrepancy of the prevalence between panorama and CBCT studies can be accounted for by the fact that CBCT provides high-resolution three-dimensional (3-D) images, which are considered to be superior in displaying mandibular canals and their variations.

10,

11 In addition, there were limitations of panoramic radiography for identifying a variation in the mandibular canal. Thus, the incidence reported by previous studies using panoramic radiography may be inaccurate and underestimated.

Failure to identify anatomical variations of the mandibular canal can complicate surgery and result in adverse consequences such as traumatic neuroma, paraesthesia, and bleeding.

16 The presence and configuration of the bifid mandibular canal are important in surgical procedures involving the mandible, such as the extraction of the impacted third molar, dental implant treatment, and orthognathic surgery of the mandibular area.

7

The incidence of bifid mandibular canals in a Korean population has not been investigated. Unlike panoramic radiography, CBCT can provide multiplanar images suited for identifying the bifid mandibular canal, without a ghost image and the false appearance of the bifid canal. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate the accurate incidence and configuration of the bifid mandibular canals in a Korean population by using CBCT.

Discussion

The bifid mandibular canal is an anatomical variation of the mandibular canal, and each separated canal might contain a neurovascular bundle. The presence and the configuration of the bifid mandibular canal are important in surgical procedures to avoid adverse consequences such as traumatic neuroma, paraesthesia, and bleeding.

Chaves-Lomeli et al

2 noted that the mandibular canal is derived from three individual nerve branches with different origins according to the developmental stage of hemimandible. As the fusion of nerve branches progresses, intraosseous membranous ossification begins and spreads around the nerve path. The extension of ossification posteriorly along the lateral border of Meckel's cartilage produces a gutter around the inferior alveolar nerve that eventually forms the mandibular canal. This theory of the development of the mandibular canal can explain the occurrence of the bifid mandibular canal in some patients, as a result of an incomplete fusion of these three nerves.

3

The incidence of bifid mandibular canals has been reported to be in the range of 0.08-0.95% in studies using panoramic radiographs. It has been reported to be 0.9% by Nortje et al,

4 0.08% by Grover and Lorton,

5 0.95% by Langlais et al,

1 0.4% by Zografos et al,

6 and 0.35% by Sanchis et al.

3 On the other hand, in studies using CBCT, the incidence of bifid mandibular canals has been reported to be in the range of 15.6-64.8%. It has been reported to be 64.8% by Naitoh et al,

7 50% by Naitoh et al,

8 46.5% by Orhan et al,

9 15.6% by Kuribashi et al,

10 and 19% by de Oliveira-Santos et al

11 Previous studies have reported that the incidence of bifid mandibular canal using CBCT was considerably higher than that obtained using panoramic radiography; in fact, the reported incidence was varied considerably in range of 15.6-64.8%.

7,

8,

9,

10,

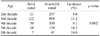

11 In the present study, the incidence of the bifid mandibular canal was 10.2%, which was lower than the number reported by the studies using CBCT. This finding can be attributed to the larger subject size used for this study. While the maximum number of subjects used in the previous studies was 484, our study considered 1933 subjects.

On a panoramic radiograph, it might be difficult to identify a mandibular canal and its variations due to the ghost shadow created by the opposing semi-mandible and overlapping with the pharyngeal airway, soft palate, and uvular.

7,

9 Furthermore, thin radiopaque lines that might give a false appearance of a bifid canal could be observed on the panoramic radiograph. These thin radiopaque lines might be formed by the imprint of the mylohyoid nerve, which separated from the inferior alveolar nerve and travelled to the floor of the mouth on the lingual surface of the mandible.

12 Moreover, the false appearance could be observed due to sclerotic lines caused by the insertion of the mylohyoid muscle into the lingual surface of the mandible, with a distribution parallel to the mandibular canal.

13 In the studies concerning the observation of the mandibular canal on a panoramic radiograph, Klinge et al

14 reported that the mandibular canal could be identified in only 63.9% of the panoramic radiographs. Lindh et al

15 also reported that the mandibular canal was clearly visible in only 25% of the panoramic radiographs. Thus, the incidence reported by previous studies using panoramic radiography might be inaccurate and underestimated. Unlike panoramic radiography, CBCT can provide a multiplanar image suitable for identifying the bifid mandibular canal, without a ghost image and the false appearance of the bifid canal. We tried to investigate the bifid mandibular canal using CBCT since the incidence in the Korean population was not investigated.

Some researchers have tried to classify the bifid mandibular canal. Nortje et al

4 published two articles following a retrospective study of 3,612 panoramic radiographs from normal clinical patients in South Africa. Three main patterns of duplication were found: type 1 (the most common) - duplicate canals originating from a single mandibular foramen, type 2 - a short upper canal extending to the second or the third molar area, and type 3 (the least common) - two canals of equal size, arising from separate foramina that join in the molar area. In their second article, they reported a new variation. Type 4 is a double-canal variation in which the supplemental canals arise from the retromolar area and join the main canals in the retromolar area.

17 On the basis of panoramic radiography, Langlais et al

1 have classified the bifid mandibular canal into four types according to anatomical location and configuration. Type 1 consists of unilateral or bilateral bifid mandibular canals extending to the third molar or the immediate surrounding area. Type 2 consists of unilateral or bilateral bifid mandibular canals that extend along the course of the main canal and rejoin it within the ramus of the body of the mandible. Type 3 is a combination of the first two categories. Type 4 consists of two canals, each of which originates from a separate mandibular foramen and then joins to form a larger canal.

1 While the abovementioned two research groups classified the bifid mandibular canal using panoramic radiography, Naitoh et al used CBCT imaging to classify the bifid mandibular canal into four types according to the origin site and the direction of the bifurcated canal from the mandibular canal. Buccal or lingual bifurcation of the bifid mandibular canal could be classified only on the basis of Naitoh's criteria because it could not be classified in other classification systems by previous researchers using panoramic radiography. Thus, our study classified the bifid mandibular canals according to the criteria of Naitoh et al

7; we used CBCT imaging for the detailed classification. In the study conducted by Naitoh et al,

7 the forward canal was found to be the most commonly occurring type of bifid mandibular canal (44.3%), whereas the buccolingual canal was found to be the least common type (1.6%). In the study conducted by Orhan et al

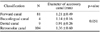

9 using the same classification, the forward canal was found to be the most commonly occurring type of bifid mandibular canal (29.8%), whereas the dental canal was found to be the least common type (8.3%). In our study, the retromolar canal was found to be the most commonly occurring type of bifid mandibular canal (54.1%), whereas the buccolingual canal was found to be the least common type (2.7%). The reported prevalence rates of each type of bifid mandibular canal were not exactly consistent with each other. However, the forward canal and the retromolar canal were the most frequently observed types in all the studies, whereas the dental canal and the buccolingual canal were the least frequently observed types (

Table 8).

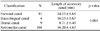

The length and the diameter of the bifid mandibular canal were studied previously. Naitoh et al

7 reported that the mean length of the bifid canal was 9.6mm(range: 1.4-25.0 mm) in the case of the forward canal, 1.6mm(range: 1.5-1.7 mm) in the case of the buccolingual canal, 8.9 mm (range: 1.6-23.0 mm) in the case of the dental canal, and 14.8mm(range: 7.2-24.5 mm) in the case of the retromolar canal. In our study, the mean lengths of the retromolar and the dental canals were 16.20 mm and 8.7 mm, respectively; these were similar to the results of Naitoh et al. However, the mean lengths of the forward and the buccolingual canals were 14.03 mm and 16.03 mm, respectively; these were inconsistent with the results of Naitoh et al. Kuribayashi et al

10 reported that the diameter of the accessory canal was greater than or equal to 50% of the main canal in 23 (49%) cases and less than 50% in 24 (51%) cases. The mean diameter of the bifid mandibular canal was 1.68mm(range: 0.88-3.40 mm), and that of the mandibular canal was 3.28 mm (range: 2.02-4.63 mm). In our study, the rate of the accessory canal, which has a diameter greater than 50% of the main mandibular canal, was also as high as 65.2%. The mean diameters of the accessory canal and the main mandibular canal were 1.27 mm and 2.85 mm, respectively; these results were similar to the results obtained by Kuribayashi et al.

The retromolar canal, opening at the retromolar foramen on the bone surface of the retromolar region, was observed most frequently in this study. Similar to the nutrient canals, the retromolar foramen and canal contain vascular and neural contents. The elements in the retromolar foramen and canal innervate and supply a part of the third molar and the mucosa of the retromolar area. Injury during surgery of the neurovascular bundle passing through this canal can lead to excessive bleeding or postoperative anesthesia.

18 Further, any prosthetic restoration or implants located distally to the retromolar area can lead to paresthesia and pain.

19 In addition to becoming an element of risk, it should be considered as a potential route for the entry of additional innervations to the lower third molar region. It has been reported that this anatomical variation provides innervations in the retromolar area, causing failure in the anesthetic mandibular blocking.

19,

20

Irrespective of the type, the presence of a bifid mandibular canal can cause some complications. Inadequate anesthesia in the mandible is the most common problem encountered in patients with a bifid mandibular canal, and it is often due to the discrepancy between the location of bifurcation and the injection point.

21 The position of bifurcation in the mandibular ramus is often superior to the most commonly administered injection point.

22 The traditional method of achieving anesthesia in the mandible is to block the inferior alveolar nerve by depositing the anesthetic solution in the pterygomandibular space at a level slightly above the mandibular foramen before it enters the mandible.

21,

23 Thus, in the case of the bifid mandibular canal, a high inferior alveolar nerve block such as the Gow-Gates technique or the Akinosi technique can be used to perform local anesthesia.

21 However, these techniques should be used only when there is definitive radiographic evidence of multiple mandibular canals and failure of the conventional inferior alveolar nerve block.

The bifid mandibular canals contain neurovascular bundles.

21 When these neurovascular bundles get injured during a surgical procedure involving the mandible, such as impacted third molar extraction, dental implant, and sagittal split osteotomy, complications such as traumatic neuroma, paresthesia, anesthesia, and bleeding during surgery may occur.

9 Moreover, in the case of trauma, all mandibular fractures should be handled with care to ensure precise alignment of the neurovascular bundle in order to avoid impingement when the fracture is reduced. Alignment of fragments becomes considerably more difficult in the case when a second neurovascular bundle is located in a different plane.

21

In conclusion, the incidence of the bifid mandibular canal is not uncommon in the Korean population with a prevalence of 10.2%, as indicated in the present study. No significant differences in the incidence with respect to gender and age were found. In the classification of the bifid mandibular canal, the retromolar canal and the forward canal were found in most of the cases. If the existence of a bifid mandibular canal is suspected in a panoramic radiograph, an advanced radiographic procedure using CBCT should be performed to confirm it. When a bifid mandibular canal is identified, the clinician must consider the need to modify the dental treatment plan to prevent complications during the treatment procedure.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download