Abstract

Purpose

This study was performed to determine the buccal alveolar bone thickness following rapid maxillary expansion (RME) using cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT).

Materials and Methods

Twenty-four individuals (15 females, 9 males; 13.9 years) that underwent RME therapy were included. Each patient had CBCT images available before (T1), after (T2), and 2 to 3 years after (T3) maxillary expansion therapy. Coronal multiplanar reconstruction images were used to measure the linear transverse dimensions, inclinations of teeth, and thickness of the buccal alveolar bone. One-way ANOVA analysis was used to compare the changes between the three times of imaging. Pairwise comparisons were made with the Bonferroni method. The level of significance was established at p<0.05.

Results

The mean changes between the points in time yielded significant differences for both molar and premolar transverse measurements between T1 and T2 (p<0.05) and between T1 and T3 (p<0.05). When evaluating the effect of maxillary expansion on the amount of buccal alveolar bone, a decrease between T1 and T2 and an increase between T2 and T3 were found in the buccal bone thickness of both the maxillary first premolars and maxillary first molars. However, these changes were not significant. Similar changes were observed for the angular measurements.

A major goal of dental orthopedics is to maximize the skeletal changes and minimize the dental changes resulting from any treatment. Rapid maxillary expansion (RME) aims to increase the width of the maxilla through skeletal expansion at the sutures. However, it has been shown that an unwanted effect of this treatment is that the teeth may become buccally tipped and displaced from their original position in the bone.1 Since the RME appliance is anchored to the teeth, the dental effects may supersede the skeletal changes in some instances.2 The periodontal consequences of RME in the permanent dentition emphasize the importance of early intervention. RME produces a greater orthopedic effect in the deciduous and mixed dentition. Despite the possibility of periodontal involvement, the future eruption of teeth will be followed by new alveolar bone, reestablishing the integrity of the area.3 In short, caution is recommended in the use of these appliances since RME represents a method whereby both skeletal and dentoalveolar changes occur simultaneously.4

Conventional radiographs, such as cephalometric and panoramic radiographs, are not appropriate for examining buccal bone or periodontal changes during and after RME therapy. These techniques are based on a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional (3D) object and do not allow the orthodontist to evaluate buccal bone widths or to measure transverse changes associated with maxillary expansion such as intermolar and interpremolar width. Furthermore, the presence or absence of buccal bone cannot be determined with conventional radiographs. Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) was developed in the 1990s as an evolutionary process resulting from the demand for 3D information. CBCT is more affordable than medical CT and requires less space.5 Therefore, it is very convenient for use in the dental office. Moreover, CBCT offers higher resolution and produces a lower radiation dose than does medical CT.5 Images that cannot be produced with traditional radiography are accessible by CBCT through the use of multiplanar reconstruction (MPR). The MPR function of the dedicated CBCT software allows coronal, sagittal, and oblique images to be created from the original axial slices from which the volume is built. CBCT software incorporates reference lines that make the location of slices simple. For example, when observing a small segment of a complete image, lines in the sagittal view and coronal view will correlate and indicate the position of the analyzed object.6 The discovery and improvement of three-dimensional imaging provides a new perspective on the effects of maxillary expansion. The purpose of this study was to utilize CBCT technology to study the post-treatment effect of maxillary expansion on the dento-alveolar region and buccal bone using expansion appliances on the maxillary complex.

Approval for the study (HSC-DB-11-0264) was granted by the Institutional Review Board of University of Texas at Houston Health Science Center. The study sample was formed retrospectively using the records of 24 individuals (15 females, 9 males; 13.9±2.4 years) that required maxillary expansion therapy as part of their comprehensive orthodontic treatment and had a complete set of images taken at specified points in time. We investigated the effects of RME therapy in non-surgical orthodontic patients. Therefore, subjects with craniofacial anomalies that would have required any type of surgical intervention were not included in the study. Individuals with prior orthodontic treatment history such as phase I treatment were also excluded from the sample.

Each patient had CBCT images available pre-expansion (T1), post-expansion (T2), and post-treatment (two-to-three years after expansion therapy; T3). Twenty-three patients had a Hyrax appliance that was either 2-banded (supported by bilateral maxillary first molars with extension of expansion arms along the gingiva of the premolars) or 4-banded (supported by bilateral maxillary first premolars and first molars). Another expansion device was included in the maxillary member of a Twin Block appliance. Maxillary expansion was started at the beginning of orthodontic treatment for all of the patients and the appliance was activated by either one or two turns (1/4 mm/turn) per day until the maxillary alveolar arch constriction was overcorrected. The total expansion time was 3-4 weeks with a mean of 22.8 days.

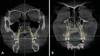

Galileos Comfort (Sirona Dental Systems GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) X-ray unit was used to capture the CBCT images of the individuals with exposure parameters of 85 kVp, 21 mA, 14 seconds, 0.3 mm voxel size and with volume dimensions of 15 cm×15 cm×15 cm. The image reconstruction time was approximately 4.5 minutes. The images were viewed and assessed with OsiriX (Pixmeo, Geneva, Switzerland). Two-dimensional coronal slices (Fig. 1) were created in order to measure the amount of dental expansion, angulation of the teeth, and buccal bone width using the reslicing function of the software. All CBCT measurements were made on standardized slices created at the level of trifurcation of the maxillary first molars and bifurcation of the maxillary first premolars perpendicular to the midsagittal plane. Palatal expansion at the maxillary first molars and first premolars was measured at the most palatal aspect of the teeth. Buccal bone measurements of the maxillary first molars and first premolars were made at the level of their trifurcation and bifurcation points, respectively. Linear measurements were recorded in millimeters, and angular measurements were recorded in degrees (Table 1).

All of the recorded data from the three points in time were compared and analyzed using one-way ANOVA analysis. Multiple comparisons were made using Bonferroni's method. The level of significance was set at p<0.05 for all statistical analyses. Records of ten random patients between T1 and T3 were used for re-measurements and an error study. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated from the original and secondary measurements.

The ICCs ranged between 0.85 and 0.98 indicating a high level of repeatability for the measurements. Both the molar and premolar width measurements (Table 2) showed significant differences among the three points in time (p<0.001). The transversal arch width measurement for the maxillary first molar increased an average of 3.95mm after expansion therapy (p<0.001) and decreased 1.66 mm between T2 and T3 (p=0.07). The arch width measurement for the maxillary first premolar increased an average of 3.58 mm following expansion (p<0.001), and decreased less than 0.1 mm between T2 and T3 (p=0.99).

With regard to changes in the angulation of the first molars and first premolars (Table 3), the only significant difference observed was between the angulation of the maxillary left first molar among the three points in time (p=0.004). Significant decreases were recorded in the angulation of the maxillary left first molar following maxillary expansion (p=0.011). At the post-treatment time point (T3), the only significant change was a subsequent increase in the angulation of the maxillary left first molar (p=0.014).

When comparing the effect of maxillary expansion on the buccal plate of the maxillary first molars and maxillary first premolars (Table 4), no significant changes were recorded for any of the teeth measured (left and right maxillary first molars and premolars). Upon the completion of maxillary expansion, a decrease in buccal plate thickness was observed for all of the teeth. However, the changes were not significant. At the postretention point in time (T3), an increase in buccal plate thickness was observed for all the teeth. The changes, however, were also not significant.

Besides the desired skeletal effects, rapid maxillary expansion can induce dental changes as well. In some instances, significant buccal tipping of the maxillary posterior teeth,1,2 periodontal consequences,3 and even tooth resorption,7,8 may be observed. According to a contemporary CBCT investigation of RME treatment, significant root volume loss was observed for all investigated posterior teeth.9 However, it was also shown that there was no significant relationship between the period of RME, the length of retention, and the total area of resorption affecting the anchor teeth.8 Additionally, it was reported that the proportion of repair tissue in the defects became greater with more prolonged retention periods.7

CBCT imaging has made it possible to examine the various aspects of the maxillofacial complex in relation to time and dental applications. It was recently shown using cadaver heads that CBCT can be used to quantitatively assess buccal bone height and buccal bone thickness with high precision and accuracy.10 In this study, CBCT technology enabled us to analyze the changes in buccal bone width following RME over time, which may not be possible with other techniques. However, as is the case with all the other radiographic imaging techniques, CBCT imaging should only be used after a careful review of the patient's health and imaging history and the completion of a thorough clinical examination.11 The CBCT images used in this study were taken from a previous collection and were investigated retrospectively. The authors of this report support the view that frequent exposure of orthodontic patients to CBCT scans with a large field of view (FOV) may not be justified.

The immediate effects of RME therapy showed reduction in buccal bone, but the reduction was not significant. Garib et al presented striking results within the short term after RME treatment such as significant expansion, buccal crown tipping, loss in the buccal plate, and bone dehiscence.3 Corbridge et al12 utilized CBCT images to demonstrate that with quad-helix appliance therapy, the teeth moved through the alveolus, leading to a substantial decrease in buccal bone thickness and increase in lingual bone thickness. While our study mainly considered the use of a hyrax expander and not a quad helix, we were not able to verify a substantial decrease in buccal bone thickness following RME since the changes were not significant. Moreover, our results demonstrated that after the completion of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances, buccal bone width is almost regained due to subsequent uprighting of the molar and premolar roots. The variability in the previous studies can be explained by the findings of Rungcharassaeng et al.13 They observed via the use of CBCT images that age, appliance expansion, initial buccal bone thickness, and differential expansion showed a significant correlation to buccal bone changes and dental tipping on the maxillary first molars and premolars, but that the rate of expansion and retention time had no significant association. They also suggested that buccal crown tipping and reduction in buccal bone thickness of the maxillary posterior teeth are the only expected immediate effects of RME, which was confirmed by our study. Our paper evaluated changes in buccal bone thickness at a follow-up period that was an average of 2.48 years post-expansion, which was not previously determined in the dental literature. The addition of a T3 point in time strengthened this study and confirmed observations that maxillary expansion can be retained.

The increase in our transversal dental width measurements following RME agreed with the results of previously published data.3-6,12,13 This increase was mostly due to skeletal expansion when RME was applied when indicated in a timely manner with no major dental side effects. Kartalian et al14 successfully demonstrated that no significant dental tipping occurred after RME treatment but significant alveolar tipping did occur. In our study, we did not measure buccal tipping of the alveolar bone. However, a significant amount of dental tipping took place in our sample group.

The findings of this study confirmed that rapid maxillary expansion was an effective method for correcting the insufficient transverse dimension of the dentition and the palate. Upon the completion of orthodontic treatment, no significant change occurred in the transversal dimension and expansion results were stable. At this time, further determining the cause and long-term consequences of moving teeth into the buccal plate is important. Additional prospective studies with a greater number of subjects in various age groups with a wide variety of expansion protocols will shine more light on the changes induced by rapid maxillary expansion. In a future study, quantification of the initial bone density in the maxilla may also be beneficial to determine whether RME is successful or not.

Based on the results of our study, clinicians should be aware that maxillary expansion could reduce the width of the buccal plate and cause tipping of the maxillary posterior teeth. However, after the completion of comprehensive orthodontic treatment by means of full fixed appliances, a subsequent increase in buccal bone width should be expected.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Two-dimensional coronal slices perpendicular to the midsaggital plane to carry out the linear and angular measurements for this study. A. Measurements of the maxillary first molar: intermolar width (1), buccal-lingual angulation of right (2) and left (3) maxillary first molar, and right (4) and left (5) maxillary first molar buccal bone thickness. B. Measurements of the maxillary first premolar: interpremolar width (1), buccal-lingual angulation of right (2) and left (3) maxillary first premolar, and right (4) and left (5) maxillary first premolar buccal bone thickness.

Table 1

List of measurements taken at T1, T2, T3 used to analyze dental effects of maxillary expansion

References

1. Adkins MD, Nanda RS, Currier GF. Arch perimeter changes on rapid palatal expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1990. 97:194–199.

2. Haas AJ. Rapid expansion of the maxillary dental arch and nasal cavity by opening the midpalatal suture. Angle Orthod. 1961. 31:73–90.

3. Garib DG, Henriques JF, Janson G, de Freitas MR, Fernandes AY. Periodontal effects of rapid maxillary expansion with tooth-tissue-borne and tooth-borne expanders: a computed tomography evaluation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006. 129:749–758.

4. Podesser B, Williams S, Crismani AG, Bantleon HP. Evaluation of the effects of rapid maxillary expansion in growing children using computer tomography scanning: a pilot study. Eur J Orthod. 2007. 29:37–44.

5. Mah JK, Danforth RA, Bumann A, Hatcher D. Radiation absorbed in maxillofacial imaging with a new dental computed tomography device. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003. 96:508–513.

6. Palomo JM, Kau CH, Palomo LB, Hans MG. Three-dimensional cone beam computerized tomography in dentistry. Dent Today. 2006. 25:130–135.

7. Langford SR. Root resorption extremes resulting from clinical RME. Am J Orthod. 1982. 81:371–377.

8. Odenrick L, Karlander EL, Pierce A, Kretschmar U. Surface resorption following two forms of rapid maxillary expansion. Eur J Orthod. 1991. 13:264–270.

9. Baysal A, Karadede I, Hekimoglu S, Ucar F, Ozer T, Veli I, et al. Evaluation of root resorption following rapid maxillary expansion using cone-beam computed tomography. Angle Orthod. 2012. 82:488–494.

10. Timock AM, Cook V, McDonald T, Leo MC, Crowe J, Benninger BL, et al. Accuracy and reliability of buccal bone height and thickness measurements from cone-beam computed tomography imaging. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011. 140:734–744.

11. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. The use of cone-beam computed tomography in dentistry: an advisory statement from the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012. 143:899–902.

12. Corbridge JK, Campbell PM, Taylor R, Ceen RF, Buschang PH. Transverse dentoalveolar changes after slow maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011. 140:317–325.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download