Abstract

It has been a challenge to establish the accurate diagnosis of developmental tooth anomalies based on periapical radiographs. Recently, three-dimensional imaging by cone beam computed tomography has provided useful information to investigate the complex anatomy of and establish the proper management for tooth anomalies. The most severe variant of dens invaginatus, known as dilated odontome, is a rare occurrence, and the cone beam computed tomographic findings of this anomaly have never been reported for an erupted permanent maxillary central incisor. The occurrence of talon cusp occurring along with dens invaginatus is also unusual. The aim of this report was to show the importance of cone beam computed tomography in contributing to the accurate diagnosis and evaluation of the complex anatomy of this rare anomaly.

Morphological variations in dental structures involving either the crown or root have often been reported in the literature. However, instances of multiple anomalies affecting one tooth have been relatively rare. Awareness of such anomalies adds to our existing knowledge of the complex process of normal and abnormal morphogenesis.

Dens invaginatus has also been called dens in dente, dilated composite odontome, dilated gestant odontome, and telescopic tooth. This developmental anomaly shows a broad spectrum of morphological variations. Dens invaginatus originates from the deepening of the enamel organ into the dental papilla prior to calcification of the dental tissues.1,2 Radiographically, the affected tooth shows an infolding of the enamel and dentin, which may extend deep into the root and sometimes reach the apex.1 In some rare cases, the invagination may be dilated and disturb the formation of the tooth, resulting in anomalous tooth development termed dilated odontome.3 According to Matsusue et al,4 a dilated odontome shows a completely inverted hard tissue structure due to severe invagination, often accompanied by central soft tissue. A tooth with dilated odontoma has a circular or oval shape with a radiolucent interior and presents a single structure, often with a central soft tissue mass.5

The incidence of dens invaginatus ranges from 0.04% to 10%, affecting either the deciduous or the permanent dentition. The teeth involved in descending order of frequency are the maxillary lateral incisors, maxillary central incisors, maxillary cuspids, mandibular incisors, and mandibular premolars. Bilateral occurrence has been noted in 43% of cases.1 Dens invaginatus may be easily overlooked with adverse effects clinically including increased risk of caries, pulp pathosis, and periodontal inflammation.1,2

Talon cusp (dens evaginatus of the anterior teeth), also known as evaginated odontome and tuberculum anomalous is a morphological anomaly presenting as a cusp-like structure projecting lingually from the cingulum area of the anterior teeth and extending towards the incisal ridge.6 Mellor and Ripa7 proposed the term talon cusp due to its resemblance to an eagle's talon. Hattab et al8 classified the talon cusp clinically into 3 types, of which Type I referred to a morphologically delineated additional cusp that prominently projects from the palatal or facial surface of a primary or permanent tooth and extends at least half the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the incisal edge. Talon cusp occurs more frequently in males. The most commonly affected tooth is the maxillary lateral incisors (55%), followed by the central incisors (36%), and canines.9

Conventional radiographs are unable to visualize tooth anatomy in three dimensions; hence, accurate diagnosis and treatment planning is challenging in cases of aberrant anatomy. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) is a contemporary radiological imaging modality overcoming various inherent limitations of conventional radiography by enabling visualization of a three-dimensional undistorted image. It permits viewing the tooth in multiple slices, including axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. Besides playing a paramount role in the early diagnosis and management of developmental anomalies of teeth, it has a wide range of clinical applications in various fields of dentistry including orthodontics, endodontics, implantology, and surgical planning. CBCT also operates with a lower radiation dose as compared to conventional computed tomography.10,11

This report revealed an unusual case of the most severe variant of dens invaginatus, known as dilated invaginated odontome, that clinically presented as a talon cusp in an erupted permanent maxillary central incisor. CBCT revealed a dilated invagination with unusual radiographic findings reflecting a severe disturbance in the morphology of the maxillary central incisor with associated talon cusp.

A healthy 24-year-old male patient visited the Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics with complaints of mild pain and swelling in relation to a maxillary left central incisor that had lasted for a week. Extraoral examination revealed no abnormality. On intraoral examination, the right mandibular first molar, which had been extracted a few months earlier due to caries, was missing. There were metallic restorations in some posterior teeth. The left maxillary central incisor had a diffuse concavity in the mid labial surface, and the tooth was labially placed in relation to the other maxillary incisors (Fig. 1A). On the palatal aspect, a pronounced cingulum, or talon cusp (Type I), was observed (Fig. 1B). The tip of the talon cusp had a deep pit formation. The tooth did not respond to an electric pulp test. The tooth was tender on percussion.

Considering the unusual anatomy observed clinically, it was decided to perform CBCT imaging (Kodak 9500 Cone Beam 3D system, Carestream Health Inc., Rochester, NY, USA) in order to evaluate the anatomy radiographically and reach a treatment plan. The exposure parameters of CBCT were 90 kVp tube voltage, 10 mA tube current, and the images were obtained with a voxel size of 0.20mm×0.20 mm×0.20 mm. The exposure time was 10.8 seconds. The images were examined with Carestream 3D Imaging software (Atlanta, GA, USA). The CBCT panoramic image of the affected tooth (Fig. 2) showed an image resembling a wide immature root apex. Based on the image and clinical symptoms, a treatment of apexification with mineral trioxide aggregate (ProRoot MTA, Dentsply, Tulsa Dental Specialties, Tulsa, OK, USA) would usually have been considered. However, as the pulp space in the crown portion was not clearly visible on the panoramic radiograph, CBCT reconstructed 3D images were examined in order to further evaluate the anatomy of the tooth prior to attempting endodontic treatment. The images focusing on the maxillary left central incisor were also obtained in sagittal, coronal, and axial planes of 200-µm slice thickness.

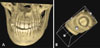

The reconstructed 3D CBCT images of the involved tooth revealed a complex structure comprising a ring-like formation of the root, and the labial view showed the root surface to be much broader than the contralateral incisor (Fig. 3). The parasagittal sections of the CBCT clearly showed the invagination between the crown proper and talon cusp and extending beyond the crown root junction, at which point the invagination dilated to form a huge ring-like structure in the root. The talon cusp also showed the presence of traces of pulpal tissue within (Fig. 4A). The CBCT axial images revealed the pulp space to be compressed and discontinuous within the ring (Figs. 4B and C).

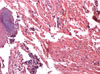

Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis of dens invaginatus of the most severe variant, termed dilated invaginated odontome, was made in the maxillary left central incisor with talon cusp associated with periapical pathology. As the CBCT revealed a very complex root canal anatomy not amenable to successful cleaning and shaping, the choice of surgical or non-surgical endodontics was ruled out. This was explained to the patient, consent obtained, and the tooth was extracted under local anesthesia. Histological examination was performed for the soft tissue within the ring-like structure. After extirpation of the soft tissue, a distinct invagination pit formation was seen at the beginning of the dilation of the root (Fig. 5). The histological examination of the contents of the invagination revealed that it was not pulp tissue but comprised of a vascular fibrous connective tissue exhibiting a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising polymorphs, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and focal aggregates of Russell bodies. Basophilic material suggestive of microorganisms was also present (Fig. 6).

Dens invaginatus is clinically important due to the possibility of the pulp being affected early and the fact that it is usually asymptomatic in the early stages and detected only on routine radiographs. Clinically, an unusual crown morphology or deep foramen caecum may hint at this phenomenon.1

Due to its simple nomenclature, Oehlers' classification12 of dens invaginatus into three categories is the most accepted. Type I and Type II involve extension only into the crown and part of the root, respectively. In Type III A, the invagination extends through the root and communicates laterally with the periodontal space through a pseudo-foramen, while in Type III B, the extension communicates with the periodontium at the apical foramen with no communication to the pulp. The incidence of Type III is the lowest (5%), while Type II is the highest (79%).13 The present report had the features of Type III B along with dilation related to root invagination. According to Alani and Bishop,2 in Type III lesions, infection in the invagination can lead to an inflammatory response within the periodontal tissues, giving rise to "peri-invagination periodontitis," as was observed in this case.

The invagination frequently allows the entry of irritants directly into the pulp tissues through a thin permeable layer of dentin. Channels may also exist between the invagination and the pulp.1 The irritants in this case could have entered the tooth either through the invagination or through the pit on the talon cusp or channels in between.

The etiology of dens invaginatus is controversial, with theories ranging from aggressive proliferation of the inner enamel epithelium or retardation of groups of cells, to pressure on the tooth germ, infection, or trauma.1-5

Treatment of dens invaginatus depends on its severity, with preventive fissure sealing recommended for Type I dens invaginatus, restoration or endodontic treatment for the invagination in Type II dens invaginatus, and an endodontic/surgical approach in the case of Type III dens invaginatus. In case of extremely bizarre anatomy such as the present case, endodontic/surgical treatment is not feasible, and extraction is advocated.1

Talon cusp is an uncommon occurrence in the maxillary central incisor. Etiological theories range from localized pressure on the tooth germ to genetic mutations.8,14 Hattab et al8 classified talon cusp into three types based on the degree of cusp formation and extension. Type I (talon) is an additional cusp that projects from the palatal surface of the permanent or primary anterior tooth and extends at least half the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the incisal edge. Type II (semi-talon) is an additional cusp but extends less than half the distance from the cemento-enamel junction to the incisal edge. Type III (trace talon) is an enlarged or prominent cingulum with variations like conical and tubercle-shaped forms.8 Talon cusp may cause occlusal interference, caries, periodontal problems, tongue irritation, and esthetic problems.15 Treatment options include fissure sealants, sequential grinding, restoration, endodontic treatment, or extraction of the affected tooth, depending on its severity.8,14,15

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report of a dilated invaginated odontome associated with talon cusp in an erupted permanent maxillary central incisor. CBCT was useful in the interpretation of this complex tooth anomaly in multiple slices along the three axes.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 3

A. CBCT three-dimensional frontal view. B. CBCT image shows the ring-like formation of the root.

Fig. 4

A. CBCT parasagittal section shows the invagination and dilation in the root portion. B. CBCT axial image at the cervical level. C. CBCT cross section at the midroot level.

References

1. Hülsmann M. Dens invaginatus: aetiology, classification, prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment considerations. Int Endod J. 1997; 30:79–90.

2. Alani A, Bishop K. Dens invaginatus. Part 1: classification, prevalence and aetiology. Int Endod J. 2008; 41:1123–1136.

3. Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral & maxillofacial pathology. 2nd Ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;2002. p. 80–81.

4. Matsusue Y, Yamamoto K, Inagake K, Kirita T. A dilated odontoma in the second molar region of the mandible. Open Dent J. 2011; 5:150–153.

5. Cuković-Bagić I, Macan D, Dumancić J, Manojlović S, Hat J. Dilated odontome in the mandibular third molar region. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010; 109:e109–e113.

6. Dumančić J, Kaić Z, Tolj M, Janković B. Talon cusp: a literature review and case report. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2006; 40:169–174.

7. Mellor JK, Ripa LW. Talon cusp: a clinically significant anomaly. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970; 29:225–228.

8. Hattab FN, Yassin OM, al-Nimri KS. Talon cusp - clinical significance and management: case reports. Quintessence Int. 1995; 26:115–120.

9. Segura JJ, Jiménez-Rubio A. Talon cusp affecting permanent maxillary lateral incisor in 2 family members. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999; 88:90–92.

11. Patel S. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: Part 2. Cone beam computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2009; 42:463–475.

12. Oehlers FA. Dens invaginatus (dilated composite odontome). I. Variations of the invagination process and associated anterior crown forms. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1957; 10:1204–1218.

13. Ridell K, Mejàre I, Matsson L. Dens invaginatus: a retrospective study of prophylactic invagination treatment. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001; 11:92–97.

14. Balcioğlu HA, Keklikoğlu N, Kökten G. Talon cusp: a morphological dental anomaly. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011; 52:179–181.

15. al-Omari MA, Hattab FN, Darwazeh AM, Dummer PM. Clinical problems associated with unusual case of talon cusp. Int Endod J. 1999; 32:183–190.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download