Abstract

Purpose

This study was performed to evaluate the uniqueness and reliability of the frontal sinuses by comparing various patterns of frontal sinus as observed on Waters' radiographs for individual identification.

Materials and Methods

Three Waters' radiographs of 100 individuals, taken on day one, after 6-8 months, and one radiograph with a slight variation in angulation, to mimic conditions out in the field or during autopsy. Three observers were randomly given radiographs from all there packets for comparisons and identification, by the method of superimposition and individual uniqueness.

Results

The comparative identification by superimposition of the frontal sinus was 100% positive. The size, shape, unilateral or bilateral presence, absence, and septa were observed to be unique in each case; neither had the measurements changed over a period of time.

Conclusion

The need to establish a reliable, low-cost, and easily reproducible method for human identification prompted the elaboration of technical, precise, and accessible parameters, such as the evaluation of the area, asymmetry, and shape of the frontal sinus. Comparison among each of the frontal sinuses of the 100 people in the sample revealed that no two sinuses are the same, that is, the sinus is unique to each individual.

The uniqueness of anatomical structures and their variations provides the basis for forensic identification of unknown deceased persons. Individual identification is a subtle concept and often one of the important priorities in mass disasters, road accidents, air crashes, fires, and even in the investigation of criminal cases. Matching specific features detected on the cadaver with data recorded during the life of the individual, which can be performed by fingerprint analysis, DNA matching, anthropological methods, and other techniques can facilitate identification. However, in cases in which the soft tissue of human remains is decomposed or burnt, or where DNA is severely tarnished, fingerprint analysis or DNA identification does not prove to be successful. In such cases, anthropological methods are used, of which comparative radiography is a major tool.

Dento-maxillofacial radiography has become a routine procedure in dental, medical, and hospital clinics. They are taken at different periods during the lifetime of large segments of the population. The radiographs are usually available when one knows where to find them. When identification is necessary, the common procedure would be to locate the dentist, physician, or hospital of the presumed victim. When this has been done, all radiographs of the person can be gathered and examined. The remains may then be radiographed under similar conditions, as in the ante mortem views.

Sinus radiography has been used for identification of remains1 and determination of sex and race.2 Schuller3 proposed a classification of the frontal sinuses from radiographs taken in the forehead-nose position. The author defined seven characteristics of the images: (1) septum and its deviation; (2) upper border (scallop, arcades); (3) partial septum; (4) ethmoidal and supra-orbital extensions; (5) height from planum; (6) total breadth; and (7) position of the sinus mid-line. Schuller, however, did not evaluate the accuracy in the method of the study. In addition, the author stated that certain diseases might alter the shape and size of the sinuses. In acromegaly, the sinuses are enormously developed; some changes may follow a chronic inflammatory condition, such as sinusitis; the cavity may disappear by new formation of bony tissue (like a sclerosed mastoid); other abnormalities may develop, as in Paget's disease, osteofibrosis cystica, and in leontiasis ossea.

In 1987 Yoshino et al4 also proposed a classification of the frontal sinuses on the basis of the following seven discrete variables: area size (left and right), bilateral asymmetry, superiority of area size, outline of superior borders, partial septa, supraorbital cells, and orbital areas. On the basis of the classification system, a class number was assigned to each morphological characteristic, and the frontal sinus patterns of a given person were formulated as a code number obtained by arranging the class numbers in each classification item as serial numbers.

The frontal sinus shows no change after the age of 20 and remains stable throughout the individual's life until old age, when gradual pneumatization can occur from atrophic changes.4

Like finger prints, even the frontal sinus is very unique in every individual, even monozygotic twins.5 Therefore, frontal sinus radiographs can be compared in order to make the identification a simple, swift, and an unambiguous procedure. Comparison of the antemortem and postmortem radiographs of the frontal sinus can be made by superimposition or coding systems.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the reliability of radiographic patterns of the frontal sinus for personal identification.

Waters' radiographs of 100 individuals were evaluated. The sample comprised 50 males and 50 females, with a mean age of 25 years, who had been previously examined and evaluated with respect to the anatomic and physiologic integrity of the frontal sinus. This study was approved by the Institutes Committee of Ethics and Research.

Only individuals in perfect health were selected to participate in the present study. Those with a history of orthodontic treatment or orthognathic surgery, trauma, or any surgery of the skull, history or clinical characteristics of endocrine disturbances, nutritional diseases, or hereditary facial asymmetries were excluded from the study.

The radiographs were taken by the same radiologist using Kodak T-MAT films (Carestream Health Inc., Rochester, NY, USA), Kodak X-Omat Lanex regular extraoral 8×10 cassettes, and a Konika New Hi Ortho screen KRII 8×10 intensifying screen (Hino, Tokyo, Japan) on a Planmeca Proline machine (Planmeca Oy., Helsinki, Finland). The radiographs were taken at 65 kVp, 10 mA, and an exposure time of 2-3 seconds.

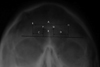

In all the radiographs, the border lines of the frontal sinus were determined with the help of a radiograph viewer and tracing paper and the following markings were made based on Ribeiro Fde's measurement criteria (Fig. 1).6

The shape of the sinus was evaluated as follows: number of septae (indentations seen on the outline of the sinus), A: diameter of frontal sinuses at the most lateral points, B: distance between the projected lines marking the highest points of the right and left sinuses, C: distance between the projected lines marking the maximum lateral limit and the highest point of the right frontal sinus, D: Distance between the projected lines marking the maximum lateral limit and the highest point of the left frontal sinus, E: line delineating the maximum lateral limit of the right frontal sinus, F: distance between upper limit of the orbital cavities and the highest point of the right frontal sinus, G: distance between upper limit of the orbital cavities and the highest point of the left frontal sinus, H: line delineating the maximum lateral limit of the left frontal sinus.

The tracing and measurement were recorded and two more radiographs of the individual were repeated after a period of 6-8 months, one with the same angulations as that of the first radiograph and another with a different angulation (+/- 3 to 5 degrees). The radiograph with changed angulations was performed to see if any change in patient positioning during the radiographic procedure led to any change in the appearance of the frontal sinus, which may have rendered it of no use for identification.

All radiographs after tracing were coded in 3 packets as 1, 2, and 3 (1: initial radiograph, 2: repeat radiograph after 6-8 months with the same parameters, 3: radiograph taken with change in angulation) and the markings and measurements were performed.

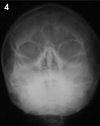

Along with the comparison of the above parameters to avoid any error that could occur due to radiographic magnification, two ratios were used for comparison, the ratio of A to F and of A to G. Three observers were randomly given radiographs from all there packets for comparisons and identification, by method of superimposition and individual uniqueness.7

One way ANOVA test was applied on the means of the groups and the p value was calculated to test the significance of the means.

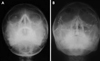

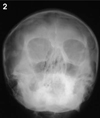

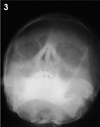

The bilateral frontal sinus was absent in 1% of the cases (1 person, Fig. 2) as against 96% (96 persons) that showed bilateral presence of the frontal sinus. Unilateral absence of a frontal sinus occurred in 3% of the cases (all three females, Fig. 3). Amongst them, the left frontal sinus was absent in one case and the right was absent in the other two. With regard to the intersinus septum, 3% had no intersinus septum (unilateral absence of the frontal sinus in three cases, Fig. 3), while a complete intersinus septum was present in 96% cases. Thirty-six cases (15 males, 21 females) had no intrasinus septum. Twenty-three cases (9 males, 14 females) had an intrasinus septum in only one side (Fig. 4). Amongst them, 10 cases (4 males, 6 females) showed the presence of an intrasinus septum on the right side and 13 cases (5 males, 8 females) showed the presence of an intrasinus septum on the left side. Forty cases (27 males, 13 females) had bilateral intrasinus septa. The number of intra-sinus septa ranged from 0 to 5 on the right side and from 0 to 4 on the left.

Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and p value for each of the parameters considered. The p value for each of the parameters was not significant, thus leading to the conclusion that the sinus had not changed over a period of time.

Some typical features of frontal sinus morphology make it a very convenient part of the human skeleton for forensic identification. Firstly, it presents a highly variable nature and shows variation even among monozygotic twins.4,5,8,9 This empirically accepted variability was proven mathematically using elliptical Fourier analysis by Christensen.10 The second feature is its relatively stable structure during adult life.9 Thirdly, the resiliency of the frontal sinus makes it useful for forensic purposes. It has very strong walls and is preserved intact in human remains11,12 as its internal bony structure and arched nature protect it from damage and decomposition. Being placed posterior to the thick outer table of the frontal bone in the glabellar region, its stability is further enhanced.13,14

It has been noted that 800-1600 foot-pounds of force is required to fracture the walls of the frontal sinus, as with victims of high impact accidents and gunshot wounds.13,14

Fourthly, paranasal sinus radiographs are commonly taken for diagnostic purposes and many people has one in his/her health records.9,15

In our study, we had 3 independent observers who had blind matched each frontal sinus radiograph, finding the other of the pair. The identification was 100% positive, thus leading to the conclusion that not a single frontal sinus might resemble any other, which means that the frontal sinuses of no two individuals might be the same thus proving the uniqueness of frontal sinus. A similar comparison was done by Kullman et al7 who blind matched 99 individual radiographs successfully by three individuals and were almost 100% successful. This showed that the radiographic image of the frontal sinus, even in hands of radiologically inexperienced observers, could be an effective identification medium.

In the present study, the overall percentage of bilateral frontal sinus absence was 1% (1 person, female), and the bilateral frontal sinus presence was 96% (96 persons). In 3% of the cases (all three females), there was unilateral absence. Amongst the three, the left frontal sinus was absent in one case and the right was absent in the other two. In the present study, the absence of the sinus or unilateral presence of the frontal sinus occurred in only 4 cases; thus, excluding them, 96 cases showed reliable reproducibility.

The p value for each of the parameters was not statistically significant, with p>0.05. This means that the difference in the values for the parameters was not statistically significant; thus the measurements have not changed over a period of time.

In the above study, we have also taken a radiograph with changes in angulation 6-8 months after the initial radiograph. Many times it is not possible to take a post mortem radiograph with the same angulation as the previous one. Therefore, a radiograph which differed by approximately 3-5° from the initial one was taken and measurements made and the sinus compared by superimposition as well. Even with the change in the angulation, the frontal sinus could be used positively for identification.

Thus, as the frontal sinus does not change over a period of time, it can be reliably used for individual identification.

In our study, one patient had trauma to the skull 3 months after the first radiograph was taken. Even after multiple fractures of the skull, the frontal sinus was preserved and appeared unchanged when the patient came for the second radiograph (Fig. 5).

In conclusion, the need to establish a reliable, low-cost, and easily reproducible method for human identification prompted the elaboration of technical, precise, and accessible parameters, such as the evaluation of the area, asymmetry, and shape of the frontal sinus. Comparison among each of the frontal sinuses of the 100 people in the sample revealed that no two sinuses are the same, that is, that the sinus is unique to each individual.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Markings based on Ribeiro Fde's measurement criteria6

|

| Fig. 5Waters' radiographs show the patient before trauma (A) and after trauma on the follow-up radiograph (B). |

References

1. Kanchan T, Krishan K, Menezes RG, Suresh Kumar Shetty B, Lobo SW. Frontal sinus radiographs-a useful means of identification. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010. 17:223–224.

2. Igbigbi PS, Nanono-Igbigbi AM. Determination of sex and race from the subpubic angle in Ugandan subjects. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2003. 24:168–172.

3. Schuller A. Note on the identification of skulls by X-ray pictures of the frontal sinuses. Med J Aust. 1943. 1:554–556.

4. Yoshino M, Miyasaka S, Sato H, Seta S. Classification system of frontal sinus patterns by radiography. Its application to identification of unknown skeletal remains. Forensic Sci Int. 1987. 34:289–299.

5. Tang JP, Hu DY, Jiang FH, Yu XJ. Assessing forensic applications of the frontal sinus in a Chinese Han population. Forensic Sci Int. 2009. 183:104.e1–104.e3.

6. Ribeiro Fde A. Standardized measurements of radiographic films of the frontal sinuses: an aid to identifying unknown persons. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000. 79:26–33.

7. Kullman L, Eklund B, Grundin R. Value of the frontal sinus in identification of unknown persons. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 1990. 8:3–10.

8. Quatrehomme G, Fronty P, Sapanet M, Grévin G, Bailet P, Ollier A. Identification by frontal sinus pattern in forensic anthropology. Forensic Sci Int. 1996. 83:147–153.

9. Cox M, Malcolm M, Fairgrieve SI. A new digital method for the objective comparison of frontal sinuses for identification. J Forensic Sci. 2009. 54:761–772.

10. Christensen AM. Assessing the variation in individual frontal sinus outlines. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2005. 127:291–295.

11. Marlin DC, Clark MA, Standish SM. Identification of human remains by comparison of frontal sinus radiographs: a series of four cases. J Forensic Sci. 1991. 36:1765–1772.

12. Nambiar P, Naidu MD, Subramaniam K. Anatomical variability of the frontal sinuses and their application in forensic identification. Clin Anat. 1999. 12:16–19.

14. Wallis A, Donald PJ. Frontal sinus fractures: a review of 72 cases. Laryngoscope. 1988. 98:593–598.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download