Abstract

A case of hemifacial hyperplasia that presented with muscular, skeletal, and dental hyperplasia along with lipomatous infiltration was described. Advanced imaging was useful in identifying the lipomatous infiltration present in the lesion, which raises the possibility of lipomatosis having a diverse presentation in hemifacial hyperplasia. As there was a scarcity of related literature in the field of dentomaxillofacial radiology, this report would make us familiar with its computed tomographic and magnetic resonance image findings.

Slight facial asymmetry is frequently observed but becomes a cause of concern if the asymmetry involves many structures and if it occurs during the growth period. Hemifacial hyperplasia is one such entity that is characterized by over-development of hard and soft tissues of head and neck region and is a rare congenital malformation. This has been termed variously in the literature as facial hemihypertrophy or partial/unilateral gigantism.1,2

Gessel3 described hemihypertrophy as 'essentially a developmental anomaly antedating birth and arising in some way as a partial deflection of the normal process of birth'. There have been various reports of hemifacial hyperplasia in the literature; however, recently, congenital fatty infiltration of the face has been reported in association with hemifacial hyperplasia. These cases have been described as congenital infiltrating lipomatosis of face and have been considered to be a possible subtype of partial hemifacial hyperplasia.4-6

The purpose of this report is to present the computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of a child with hemifacial hyperplasia and congenital fatty infiltration of the face. As there are not many reported cases of this developmental disorder in the field of maxillofacial radiology, this report aims to highlight the role of advanced imaging techniques in hemifacial hyperplasia and to supplement existing clinical knowledge.

A 5-year-old female patient visited the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology with a complaint of pain in the region of the right posterior teeth of the lower jaw. Her mother also reported that her daughter had shown an asymptomatic swelling on the right side of her face since birth. The patient had undergone examination of this condition at 8 months of age. There was history of a gradual increase in the extent of the swelling with age, and the asymmetry of the face persisted. The child was born at full term with normal delivery and there was no history of consanguineous marriage in the family. The child was of normal build and intelligence. There was no familial history of such complaints in the family and serum chemistry revealed no abnormalities.

The swelling over the face extended from the zygomatic arch up to the lower border of the mandible on the right side. It was diffuse and had a sponge-like consistency. It was large enough to cause obliteration of the nasolabial fold and the right corner of the mouth seemed to be drooping. No other physical abnormality was noted (Fig. 1).

Intraoral examination revealed that the cause of pain was the carious right mandibular deciduous second molar. It was also noticed that premature eruption of the permanent mandibular incisors and first molar, and of the maxillary molar was found on the right side. The tongue was also hypertrophic on the right side with noticeably enlarged papillae. The buccal mucosa and gingiva appeared normal (Fig. 2).

Panoramic radiograph showed that the right mandibular body and ramus were asymmetrically large in size. There was accelerated development of the maxilla and mandible on the right with advanced eruption of the teeth as compared to the left. Radiographic analysis also revealed that all of the teeth on the right side had accelerated root formation relative to their counterparts on the left side. The condyle and the coronoid process on the right side were large with a prominent sigmoid notch. Multiple carious teeth were also noted (Fig. 3).

MRI examination revealed the presence of a diffuse lipomatous tissue (which appeared bright or hyperintense on T1 weighted images) in the right cheek region and the region of the pterygomandibular space. There was fatty infiltration in the tissues anterior to the wall of the maxillary sinus and adjacent to the mandible on the right side. Other features of asymmetric enlargement of the right side of the face were also noted (Fig. 4).

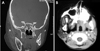

Axial and coronal CT scan sections showed a large markedly hypodense well defined mass causing severe swelling of the right cheek. The lesion extended from the infratemporal fossa superiorly to the lower border of the mandible inferiorly. The interior of the lesion had multiple enhancing hyperdense septae; however, the lesion itself did not appear to be enhanced after contrast administration. The right side of the mandible, coronoid process and condyle, maxillary sinus, and pterygoid plates including the masseter and the base of the skull were larger than the left side structures (Figs. 5 and 6).

The CT and MRI findings were suggestive of a benign soft tissue mass of fat like density with enlargement of the mandible and base of the skull on the right side suggestive of a developmental anomaly. The infiltration of diffuse fatty tissue around the mandible is suggestive of lipomatosis like lesion in association with hemifacial hyperplasia.

Rowe7 described the criteria for true hemihypertrophy. According to the report, hemifacial hypertrophy is an unusual condition that produces facial asymmetry by a marked unilateral localized overgrowth of all of the tissues in the affected area, i.e. facial soft tissues, bone, and teeth. The unilateral enlargement of the viscerocranium is bounded by the frontal bone superiorly (not including the eye), inferiorly by the border of the mandible, medially by the midline of the face, and laterally by ear, the pinna being included within the hypertrophic area. The disorder occurs more commonly in females (ratio 3:2).

Heredity, chromosomal and neural abnormalities, atypical forms of twinning, altered intrauterine environment, endocrine dysfunctions, anatomical and functional anomalies of the vascular and lymphatic systems, and disturbances of the central nervous systems are implicated in its etiology. 8-10 Pollock et al2 hypothesized that asymmetric development of the neural fold and hyperplasia of the neural crest cells are both responsible for unilateral growth of crest cell-derived bone, muscle, and derived tissues. Yashimoto et al11 concluded that fibroblast growth factor and its receptor signal transduction axis may be selectively involved in the affected osteoblasts, leading to hypertrophy.

Based on the clinical and radiographic findings, it was concluded that most of the findings were consistent with the oral and facial characteristics of facial hemihypertrophy. The enlargement of the teeth on the affected side, as a diagnostic aid in hemifacial hypertrophy, has been supported by Rushton.12 The findings of enlargement of the tongue and its papillae on the involved side was also seen in our case. No abnormality of the skin was noted on the affected side, as reported by Gorlin and Meskin.13

In hemifacial hyperplasia, asymmetry becomes accentuated with age. It may be detected at birth, but becomes more apparent as the affected part enlarges at a greater rate than the rest of the body. As in a previous study,14 the right side is more commonly affected. Twenty percent of the reported cases had some degree of mental retardation.3 A similar growth pattern and asymmetrical enlargement were noted on the right side in our case; however there were no signs of mental retardation.

In our case, both CT and MRI revealed that facial asymmetry was caused by enlargement of both subcutaneous tissues and the underlying skeleton. Apart from enlargement of the masseter, maxilla, mandible, and dental tissues, there was lipomatous tissue infiltration on the same side. Some authors reported lipomatosis without the enlargement of the muscles.4,5 The clinical signs and advanced imaging in our case showed certain similarities with those of congenital infiltrating lipomatosis of the face. Bou-Haidar et al5 suggested that hemifacial lipomatosis might be a subtype of partial hemifacial hyperplasia. As reported by Bou-Haidar et al5 and Sugiyama et al,4 lipomatosis was the dominant feature with the lack of significant muscular hyperplasia. However, in our case there was considerable enlargement of the muscles as well as the underlying skeletal and dental tissues.

Hemifacial hyperplasia should be differentiated from other conditions that cause unilateral asymmetrical enlargement of the face such as fibro-osseous lesions, Paget's disease, soft and hard tissue tumours such as haemangioma, lymphangioma, and cystic hygroma, neurofibromatosis, Beckwith Weideman syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, and Parry-Romberg syndrome. The presence of precocious eruption and unilateral enlargement of the affected tooth regions also provides an important indication for the diagnosis of hemifacial hyperplasia. Dental abnormalities include precocious eruption, which may be as advanced as up to 4-5 years, macrodontia, and root resorption abnormalities.13 Advanced imaging can provide vital information regarding the nature of swelling in such cases and help to rule out conditions such as haemangioma, which also affects the eruption of teeth.

Wilms' tumors, hepatoblastoma, and adrenal cell carcinoma were known to be associated with hemifacial hypertrophy.5 Patients should be screened and proper follow-up examinations should be performed to rule out abdominal malignancies. The treatment of hemifacial hyperplasia should be performed once complete growth of the facial skeleton is achieved and consists of reconstructive surgeries and ostectomies, orthognathic surgery, and soft tissue excision.

To conclude, congenital infiltrating lipomatosis may be an unusual type of hemifacial hyperplasia. The application of CT and MR imaging in such developmental disorders can be of immense help in performing the differential diagnosis and determining the nature of the lesion non-invasively.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 2Intraoral photograph shows the precocious eruption of teeth and enlarged tongue papillae on the right side. |

| Fig. 3Panoramic radiograph shows the premature eruption and accelerated root formation of teeth on the right side. |

| Fig. 4Coronal (A) and axial (B) MR images show a well-encapsulated mass which appears bright on a T1 weighted image. |

References

1. Ringrose RE, Jabbour JT, Keele DK. Hemihypertrophy. Pediatrics. 1965. 36:434–448.

2. Pollock RA, Newman MH, Burdi AR, Condit DP. Congenital hemifacial hyperplasia: an embryologic hypothesis and case report. Cleft Palate J. 1985. 22:173–184.

3. Gessel A. A further study of the nature of hemihypertrophy with report of a new case. Am J Med Sci. 1927. 173:542–554.

4. Sugiyama M, Tanaka E, Ogawa I, Ishibashi R, Naito K, Ishikawa T. Magnetic resonance imaging in hemifacial hyperplasia. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2001. 30:235–238.

5. Bou-Haidar P, Taub P, Som P. Hemifacial lipomatosis, a possible subtype of partial hemifacial hyperplasia: CT and MR imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010. 31:891–893.

6. De Rosa G, Cozzolino A, Guarino M, Giardino C. Congenital infiltrating lipomatosis of the face: report of cases and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987. 45:879–883.

7. Rowe NH. Hemifacial hypertrophy. Review of literature and addition of four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1962. 15:572–587.

8. Azevedo RA, Souza VF, Sarmento VA, Santos JN. Hemifacial hyperplasia: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2005. 36:483–486.

9. Fraumeni JF Jr, Geiser CF, Manning MD. Wilm's tumor and congenital hemihypertrophy: report of five new cases and review of literature. Pediatrics. 1967. 40:886–899.

10. Rudolph CE, Norvold RW. Congenital partial-hemihypertrophy involving marked malocclusion. J Dent Res. 1944. 23:133–139.

11. Yoshimoto H, Yano H, Kobayashi K, Hirano A, Motomura K, Ohtsuru A, et al. Increased proliferative activity of osteoblasts in congenital hemifacial hypertrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998. 102:1605–1610.

12. Rushton MA. A dental abnormality of size and rate. Proc R Soc Med. 1948. 41:490–496.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download