INTRODUCTION

For men, the preferred position of voiding is dependent on several variables, including the type of available toilet facility, social behavior, and associated musculoskeletal comorbidities. For example, a man may void in a sitting or standing position at home on a commode but may void in a standing position while in the office or outdoors.

Uncertainty remains whether it is best for men to void in a sitting or standing position and how to determine the best voiding position. The existing literature on uroflowmetry in different positions is limited, and studies documenting uroflowmetry parameters in different positions provide conflicting and inconsistent results [

123456789101112]. Some studies have reported higher flow rates in a standing position [

3], while other studies have reported a sitting [

58], squatting [

7], or even a prone position as optimal for flow rate [

2]. The heterogeneity in the age of the study populations in these studies has made the interpretation of the results difficult.

In 2014, de Jong et al [

13] conducted a systematic review and a meta-analysis to determine the beneficial effects of voiding position on an individual's urodynamic profile. Based on the available studies, the meta-analysis concluded that patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) performed better in the sitting voiding position than in the standing position. However, no superior voiding position for healthy men was found. A major limitation to the review was the diminished power from the small number of studies that may have left the results prone to misinterpretation [

13].

We hypothesized that the best position for voiding would allow for the completion of urination within a reasonable duration, with an adequate urinary flow, and would leave behind no residual urine in the bladder.

Voiding position is of limited importance for normal, asymptomatic men who are younger than 50 years old. However, there is a tendency for incomplete bladder emptying and poor urinary stream as men age, so the impact of voiding position may be important for these men. Elderly men have also stated that they have an optimal voiding position, whether it be in the sitting or standing position [

14].

We conducted this study to determine whether the voiding position influenced uroflowmetry parameters in subjects belonging to different age groups, and to determine whether it affected post-void residual urine (PVRU).

Go to :

RESULTS

A total of 863 men were enrolled during the study period. From this group, 123 men were excluded, including men who were unable to complete both required uroflowmetry tests and men whose uroflowmetry curves were not representative of a normal flow (i.e., a straining pattern or a cruising pattern). The remaining 740 men were included in the analysis. The study population had a mean age of 40.35±14.42 years (range, 18~77 years) and a mean body mass index of 22.27±3.58 kg/m2 (range, 15.8~36.7 kg/m2).

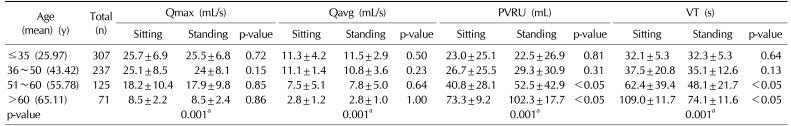

The uroflowmetry parameters in the sitting and standing positions among different age groups are shown in

Table 1.

Table 1

Uroflowmetry parameters in the sitting and standing positions among different age groups

|

Age (mean) (y) |

Total (n) |

Qmax (mL/s) |

Qavg (mL/s) |

PVRU (mL) |

VT (s) |

|

Sitting |

Standing |

p-value |

Sitting |

Standing |

p-value |

Sitting |

Standing |

p-value |

Sitting |

Standing |

p-value |

|

≤35 (25.97) |

307 |

25.7±6.9 |

25.5±6.8 |

0.72 |

11.3±4.2 |

11.5±2.9 |

0.50 |

23.0±25.1 |

22.5±26.9 |

0.81 |

32.1±5.3 |

32.3±5.3 |

0.64 |

|

36~50 (43.42) |

237 |

25.1±8.5 |

24±8.1 |

0.15 |

11.1±1.4 |

10.8±3.6 |

0.23 |

26.7±25.5 |

29.3±30.9 |

0.31 |

37.5±20.8 |

35.1±12.6 |

0.13 |

|

51~60 (55.78) |

125 |

18.2±10.4 |

17.9±9.8 |

0.85 |

7.5±5.1 |

7.8±5.0 |

0.64 |

40.8±28.1 |

52.5±42.9 |

<0.05 |

62.4±39.4 |

48.1±21.7 |

<0.05 |

|

>60 (65.11) |

71 |

8.5±2.2 |

8.5±2.4 |

0.86 |

2.8±1.2 |

2.8±1.0 |

1.00 |

73.3±9.2 |

102.3±17.7 |

<0.05 |

109.0±11.7 |

74.1±11.6 |

<0.05 |

|

p-value |

|

0.001a

|

0.001a

|

0.001a

|

0.001a

|

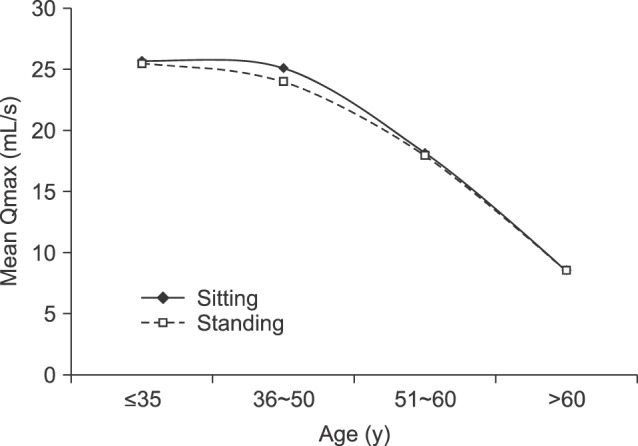

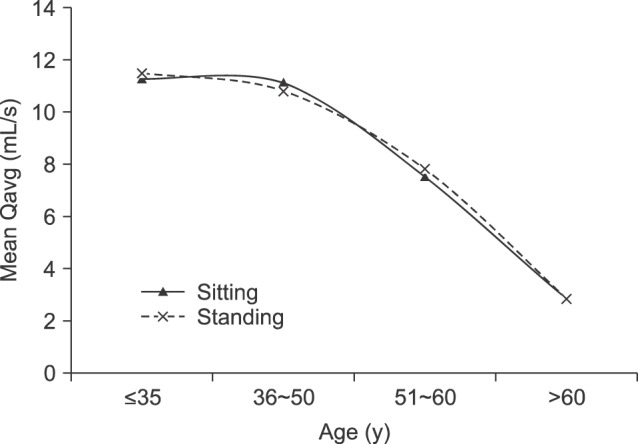

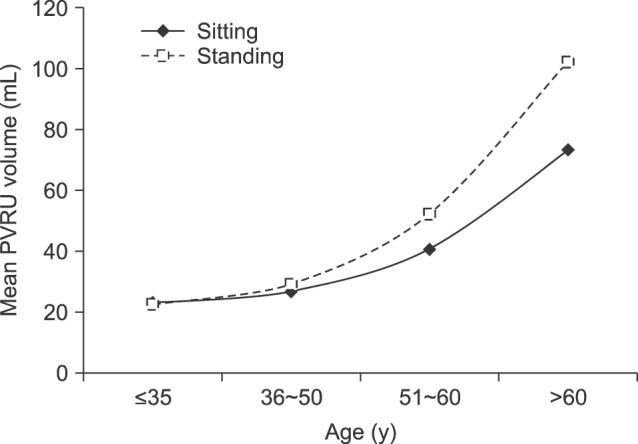

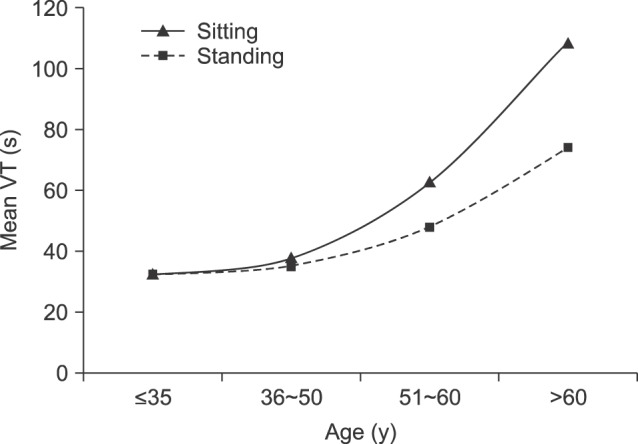

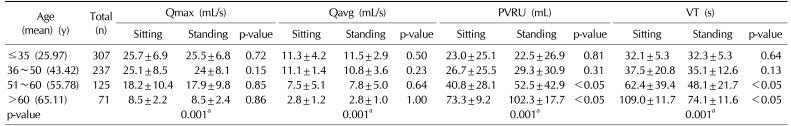

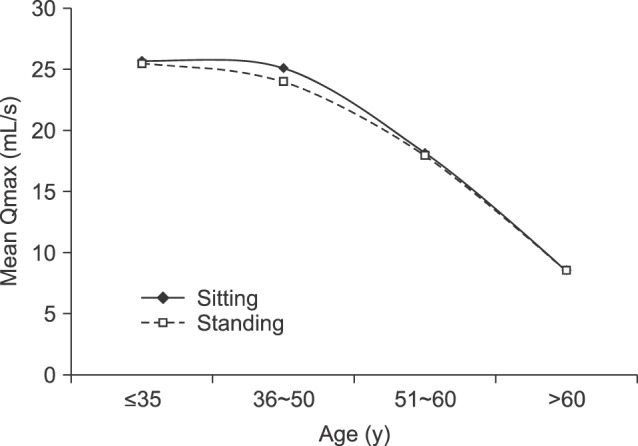

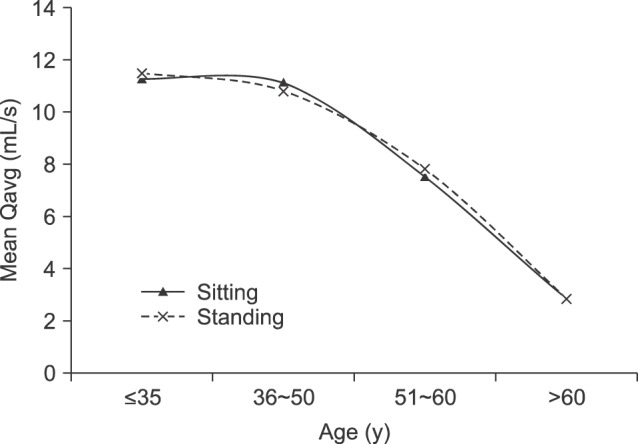

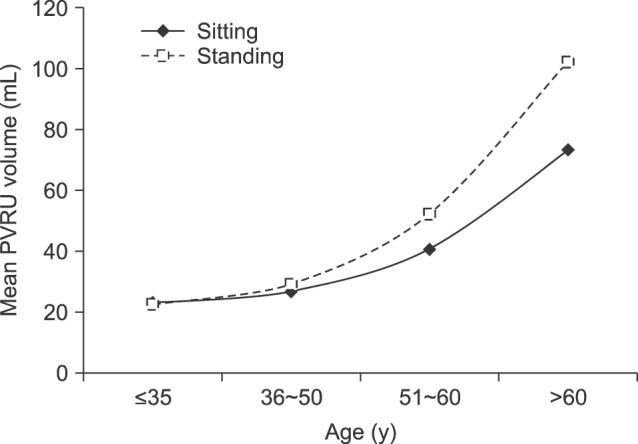

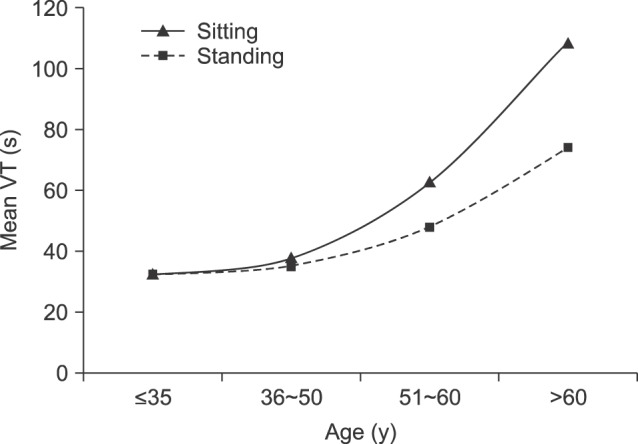

Fig. 1,

2,

3,

4 show the comparison of uroflowmetry parameters between sitting and standing positions by age. There was no significant difference in uroflowmetry parameters until the age of 50 years old. After 50 years old, PVRU volumes were significantly lower in the sitting position than in the standing position, whereas the voiding time was significantly higher in the sitting position than in the standing position. Other uroflowmetry parameters, including the maximum urinary flow rate and the average urinary flow rate, did not significantly differ between the sitting and standing positions, even after the age of 50 years old.

| Fig. 1The maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) in the sitting and standing positions among different age groups.

|

| Fig. 2The average urinary flow rate (Qavg) in the sitting and standing positions among different age groups.

|

| Fig. 3Post-void residual urine (PVRU) volumes in the sitting and standing positions among different age groups.

|

| Fig. 4Voiding time (VT) in the sitting and standing positions among different age groups.

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

BPE remains a global health issue in those with advancing age. Today, the majority of patients with BPE can be managed using medications like alpha-blockers and 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors. However, some patients do not prefer pharmacotherapy or are unable to tolerate the side effects. Men with mild symptoms of BPE are often managed conservatively with lifestyle modifications. These modifications include smoking cessation, increased physical activity, obesity control, blood pressure control, and increased fruit and vegetable intake [

15]. Changing the voiding position may have an effect that is equivalent to the effects of pharmacological management [

16]. The available guidelines do not include any recommendations regarding the position for urination. According to the guidelines provided by the European Association of Urology, men with mild LUTS are advised to monitor their symptoms, and men with LUTS should always be offered lifestyle advice prior to or concurrent with treatment (level of evidence 1b, grade A).

The role of PVRU in the management of BPE remains controversial. In the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms trial, Roehrborn et al [

17] documented PVRU as a weak predictor of outcomes during treatment for benign prostatic hyperplasia. However, significant PVRU may increase urinary frequency and may also be a reason for infection [

18].

In rural India, the squatting position for voiding is not uncommon among men who void in farms and fields. Only a few studies have compared the squatting position with other positions among men [

1789]. Some authors have reported more optimal urinary flow results with squatting [

179], while other authors have observed the contrary [

8]. Despite the lack of data, it seems that men are less often to clinically present with voiding symptoms in rural India. Therefore, the question of whether voiding in the squatting position protects the elderly rural population from clinically significant symptoms still remains to be answered. However, even if voiding in the squatting position is optimal, it may not be feasible to recommend this position to elderly men who may simultaneously have knee joint arthritis. We had intended to include the squatting position as part of this study, but failed to do so, as it was difficult to ask the volunteers to void so many times. In fact, many volunteers had to be excluded due to their failure to provide results for 2 different positions, exhibiting the difficulty in procuring even 2 reliable uroflowmetry parameters.

We included men on medication with an IPSS <10, as it was difficult to recruit elderly men with an IPSS <7 who were not on any medications. Most volunteers were attendants who accompanied patients within the clinics or took care of admitted patients.

Our results showed that elderly men who voided in a sitting position had lower PVRU volumes. This may have been due to an increase in voiding time, as participants felt more comfortable in the sitting position. One patient mentioned that he has a library of books in the washroom, and he sits on the commode to void while reading. This patient waited until his bladder was empty by double or triple voiding. It is possible that elderly men feel tired while voiding in the standing position and in their hurry fail to empty the bladder completely. However, personal preference in position may explain the variations in PVRU. In clinical practice, some men say that they void more easily while standing and that their stream is better in this position. In our study, we found that men who were older than 50 years old had lower PVRU volumes in the standing position (31 of 196 men).

Voiding time was found to be longer in the sitting position. However, the majority of elderly men were homebound and not actively working. They, therefore, did not mind spending extra time voiding in the sitting position.

El-Bahnasawy and Fadl [

5] studied 200 patients with LUTS and a mean age of 51.85±14.48 years to compare urinary flow in the sitting and standing positions. They found that a patient's preferred voiding position and uroflowmetry test should always be performed in his preferred position. Similar results were found by Aghamir et al [

8].

Choudhury et al [

9] studied 61 healthy men with a mean age of 26.6±6.9 years to evaluate the role of natural voiding position on urinary flow (a comparison of sitting, standing, and squatting). They found that the urinary flow rate was lower in the sitting position than in the standing or squatting positions. Similarly, Yazici et al [

12] studied uroflowmetry parameters in 198 men with flank pain (including men with and without BPE) and a median age of 58 years (range, 36~69 years) in the sitting and standing positions and concluded that the optimal voiding position was one in which the patient felt most comfortable. The shortcomings of these studies were the small number of patients and the heterogeneous study populations.

Authors who reported significant changes in uroflowmetry parameters according to the voiding position provided a variety of explanations for their findings. El-Bahnasawy and Fadl [

5] proposed that positional changes of the pelvic floor and thigh muscles (with greater relaxation in the sitting rather than the standing position) had an impact on the uroflowmetry parameters. Aghamir et al [

8] reported that men with borderline lower urinary tract function (e.g., patients with BPE) had a more obtuse angle between the bladder and the urethral axes while sitting, which may be better for bladder emptying. The authors also suggested that the altered geometry and shape of a voiding bladder may be a possible cause of lower flow in the supine position than the standing position [

3]. Eryildirim et al [

1] found that flow was better in the squatting and sitting positions than the standing position. They attributed this to the change in intra-abdominal pressure that is followed by a higher pressure transmission on the urinary bladder in the squatting and sitting positions.

A meta-analysis conducted in 2014 concluded that voiding position had no meaningful impacts on urodynamic parameters in healthy individuals and that the sitting position had a positive effect on the management of LUTS. This meta-analysis found only 11 full-text articles after an extensive database search, with a total study population of 800 participants that included a majority of studies with a sample size of less than 50. No conclusive information can be obtained from such small sample sizes. In addition to variations in sample size, these studies were heterogeneous in terms of age and the inclusion of volunteers or patients with LUTS. Our study is the largest available study assessing the impact of the voiding position on urodynamic parameters. By comparing urodynamic parameters in the sitting and standing positions with respect to the age of the patients, we have obviated heterogeneity and strengthened our findings [

13].

Currently, there are no recommendations about voiding position in the management of men with voiding dysfunction (including men with BPE). However, our results suggest that voiding in the sitting position should be recommended as an ancillary lifestyle modification during the management of these patients.

A limitation to this study was the small sample size, particularly of elderly men. This can be attributed to conducting our study in a hospital, which made it difficult to recruit men with mild symptoms. The subjects were also on a variety of different alpha-blockers, including tamsulosin, alfuzosin, and silodosin. However, we considered the effectiveness of alpha-blockers to be equal in this study and, thus, we did not evaluate them separately [

19]. We also did not ask the men about their preferred voiding position. Furthermore, the order in which the patient voided was not standardized. This could have affected the results, as uroflowmetry parameters can change with repetition. We also excluded men with an IPSS ≥10, possibly overlooking important clinical information, and we did not analyze the correlation between prostate volume and the uroflowmetry parameters.

We were able to recruit a large number of volunteers, which is the greatest strength of this study.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download