Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and the factors influencing the healthcare-seeking behavior of men with LUTS.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional survey was performed of 658 men selected using multi-staged sampling techniques. They were interviewed about LUTS and their healthcare-seeking behavior. The data were analysed using PASW Statistics ver. 18. Associations between specific factors and healthcare-seeking behavior were examined using the chi-square and Fisher exact tests.

Results

The overall prevalence of LUTS was 59.1%. Storage symptoms (48.2%) were more prevalent than voiding (36.8%) or post-micturition (29.9%) symptoms. Approximately a quarter (25.5%) had a poor quality of life (QoL) score. The average duration of symptoms before seeking help was 3.4 years. Almost half (46.8%) of the men with LUTS had never sought help. Perceptions of LUTS as an inevitable part of ageing, subjective feelings of wellness, financial constraints, and fear of surgery were the most common reasons for not seeking help. The most common reasons for seeking help were to moderate-severe symptoms, impaired QoL, and fear of cancer. Severe LUTS, impaired QoL, and the concomitant presence of erectile dysfunction, dysuria, or haematuria were clinical factors that positively influenced healthcare-seeking behavior.

Conclusions

In this population-based study, we found that the prevalence of LUTS was very high amongst adult males. However, only about half of these men sought medical attention. Their healthcare-seeking behavior was influenced by severity of symptoms, QoL scores, and socio-demographic factors such as educational status.

Prostate diseases manifesting as lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) constitute a major health burden in adult males. It is well known that the prevalence of LUTS in the community exceeds that which comes to the attention of healthcare professionals [1]. The processes involved in seeking healthcare are complex and affected by many factors such as the salience of signs and symptoms, competing needs and lay referral networks. Although significant research has been carried out on LUTS and prostatic diseases, very little research has investigated why men suffering from LUTS fail to seek medical attention [2].

Although the presence of symptoms is an important reason for seeking treatment, it is not the only factor. Some men with severe symptoms never seek treatment, while others with relatively mild symptoms do so early. Whether a man eventually seeks and undergoes treatment depends on a sequence of events that includes the impact of symptoms on health status and quality of life (QoL); treatmentseeking behavior and informed patient preference [2]. It has been documented that in Caucasian men, LUTS have a significant negative impact on QoL leading many to seek medical treatment [3]. Another study demonstrated differences according to the race in the utilisation of health services for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) complaints, with African-Americans found to be less bothered given the same severity of LUTS, which may in turn result in differential healthcare-seeking behavior [4].

A major concern is why many patients with LUTS do not present to health facilities seeking medical attention. This may partly be due to poor healthcare-seeking behavior, amongst other factors [5]. Factors that determine the healthcare-seeking behavior of men with LUTS include socio-demographic and clinical factors as well as men's perceptions of their symptoms. Clinical determinants of healthcare-seeking behavior that have been identified include the predominance of some symptoms, severity of symptoms, and the degree to which a patient's QoL is affected. A study characterizing these factors in the social environment of Nigeria will help to direct efforts to improve healthcare-seeking behavior which may ultimately reduce morbidity and mortality from prostatic diseases following delayed presentation.

Moreover, there is paucity of data regarding the prevalence LUTS, perceptions of those symptoms, and the healthcare-seeking behavior of sub-Saharan African men. Given the known poor healthcare-seeking attitude of Africans and Nigerians, it will be beneficial to determine the factors that lead Nigerian men to seek care in a community setting [6]. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to determine the prevalence of LUTS, to characterize the healthcare-seeking behavior of Nigerian men, and to identify the determinants of healthcare-seeking behavior of community-dwelling men with LUTS.

This was a questionnaire-based descriptive cross-sectional survey carried out amongst 658 adult males in the Ido/Osi Local Government Area of Ekiti State, Southwest, Nigeria. Approval for the study was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos. The target population was male adults over 40 years of age. Participants were selected using a multi-stage sampling technique. This involved the selection of 3 of the 11 electoral wards in the study area followed by the selection of 1 community from each selected ward. In each community, 15 to 20 streets were selected. These 3 stages were carried out using a simple randomsampling technique by balloting. Between 10 to 15 of the houses were selected in each community by systematic random sampling. Amongst all men above 40 years of age in each selected house, an individual was chosen randomly for the survey. All men selected and who consented to participate were recruited for the study. Each subject was interviewed about the presence of individual LUTS and associated symptoms. For those with a history of LUTS, the severity of their symptoms was assessed using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire, including the QoL score. Information was collected from the men using a structured questionnaire composed of the following 4 parts: socio-demographic data, clinical symptoms, perception of symptoms and healthcare-seeking behavior. Data were collected by visiting the selected men in their houses on 3 consecutive weekends.

The data were analysed using PASW Statistics ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and results were displayed using simple proportions in tables and charts. Associations between various factors and the perceptions and healthcare-seeking behavior of the participants were explored using the chi-squared and Fisher exact tests.

A total of 658 adult men were interviewed, ranging in age from 41 to 93 years, with a mean age of 64.1±12.5 years. The age ranges of 51 to 60 years and 61 to 70 years accounted for more than half (51.2%) of the entire study population.

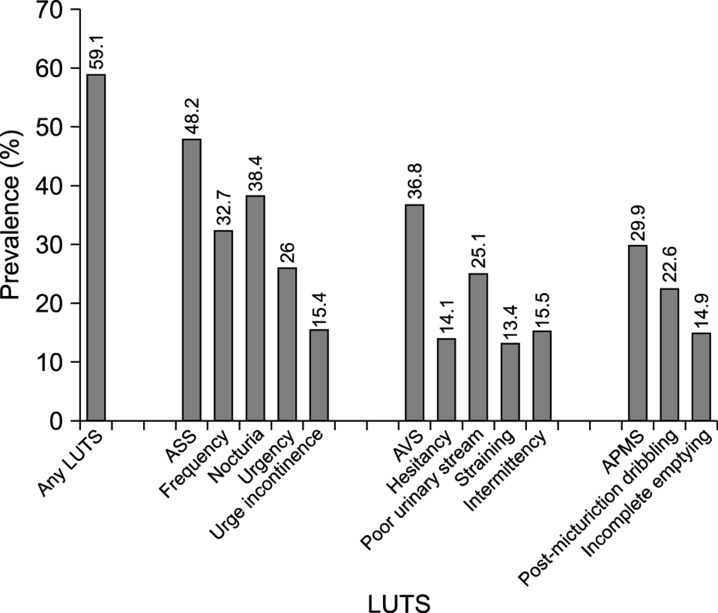

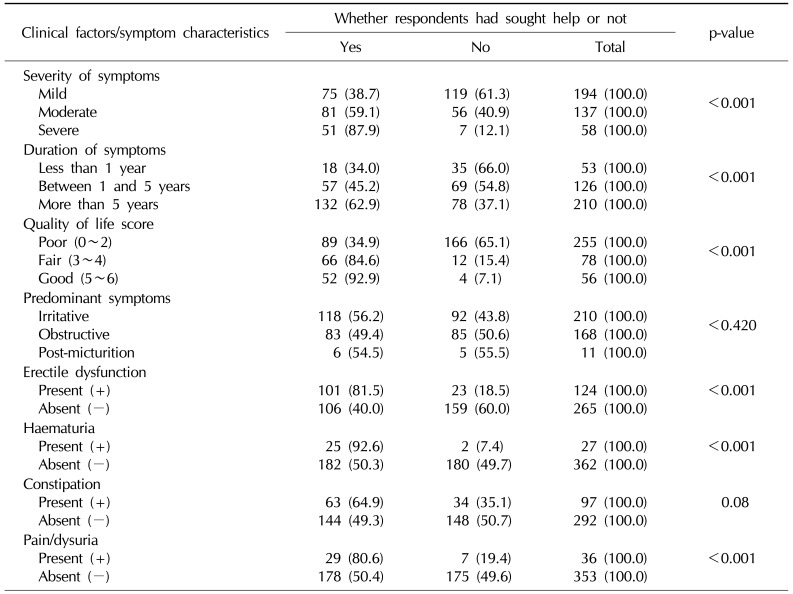

Amongst the 658 respondents, 389 had at least one LUTS equivalent to an overall prevalence of 59.1% while 269 men (40.9%) had no LUTS. A total of 317 participants had at least 1 storage symptom, 242 had a least 1 voiding symptom, while 197 had at least 1 post-micturition symptom, corresponding to prevalences of 48.2%, 36.8%, and 29.9%, respectively. Nocturia was the single most common symptom, found in 253 men (38.4%), whereas straining was the least common, found in 88 men (13.4%). Details of the frequencies of other symptoms are presented in Fig. 1.

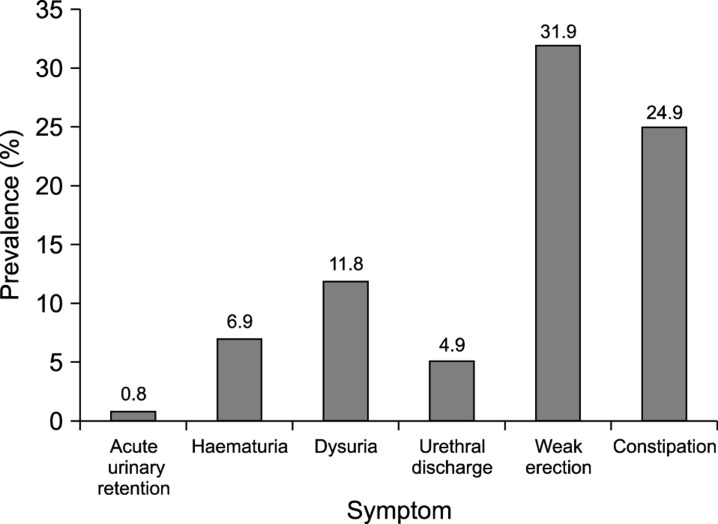

Fig. 2 shows the frequency of other symptoms associated with LUTS in men with symptoms. The most common associated symptoms were weak erection in 124 respondents (31.9%) and constipation in 97 respondents (24.9%).

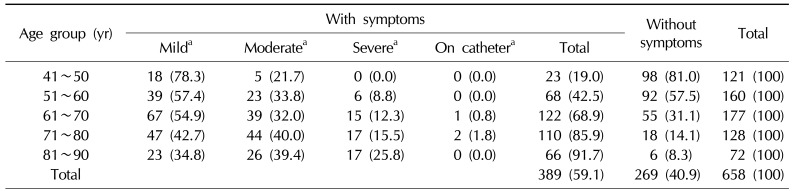

The distribution of symptoms according to age and symptom severity in symptomatic men is presented in Table 1. Overall, 194 symptomatic men (29.5%) had a mild IPSS score while 137 (20.8%), and 55 (8.4%) had moderate and severe IPSS scores, respectively. Three men had been catheterised for an episode of acute urinary retention before the survey and therefore had no IPSS score.

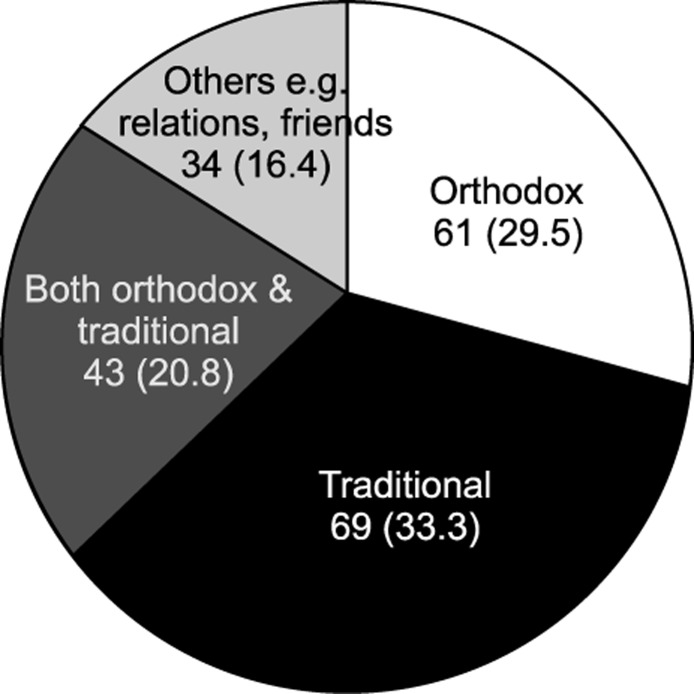

Of all respondents with LUTS, only 207 (53.2%) had ever sought medical attention, while 182 (46.8%) had never done so. Fig. 3 shows the various sources where men with LUTS sought medical assistance. The average duration of symptoms before seeking help was 3.4 years.

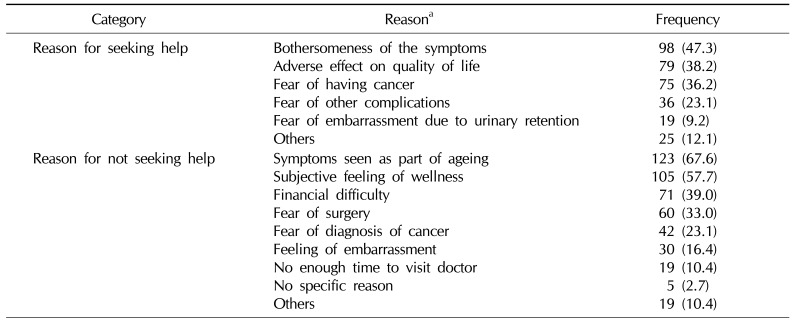

The bothersomeness of LUTS and impaired QoL were 2 most common reasons for seeking medical attention (in 47.3% and 38.2% of respondents, respectively), while perception of the symptoms as part of the ageing process and subjective feelings of wellness were the most common reasons for not seeking medical attention (in 67.6% and 57.7% of respondents, respectively). Details regarding the other reasons are presented in Table 2.

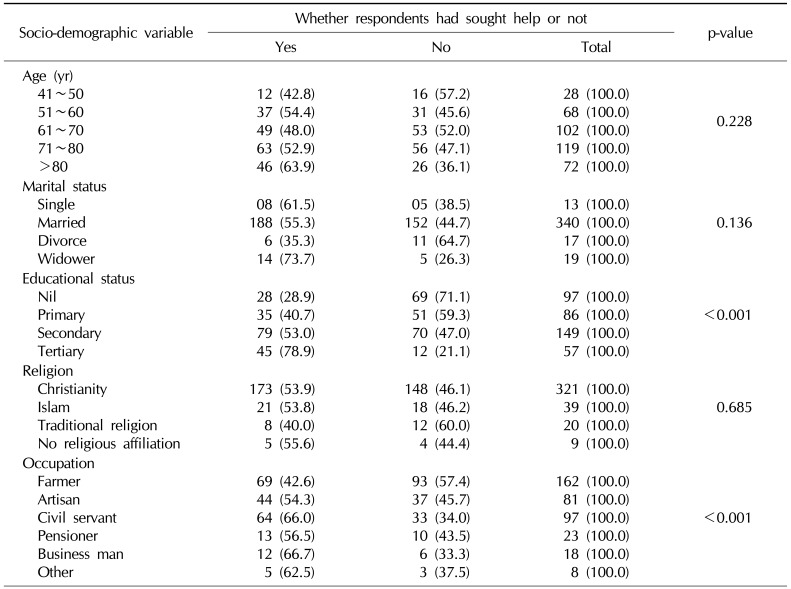

Of all the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents in this study, only educational status and occupation had a significant positive relationship with healthcare-seeking behavior. Other details are presented in Table 3.

The relationships between various clinical parameters are presented in Table 4. Only symptom severity, the QoL score, and the concomitant presence of erectile dysfunction (ED), haematuria, or dysuria were shown to influence healthcare-seeking behavior.

LUTS commonly affect middle-aged and elderly men. The present study provides insights into the prevalence of LUTS among Nigerian men. In this population-based study of Nigerian men above the age of 40 years, we found the overall prevalence of LUTS to be 59.1%. This is within the range of prevalence values documented in previous epidemiologic surveys from different parts of the world, although considerable variety has been reported in the prevalence of LUTS (13% to 67%) [78]. When analysed by age, the prevalence of LUTS shows a steady rise with advancing age, from 19.1% in the fifth decade to above 90% in men above the eighth decade of life. Consistent with other epidemiologic studies, our study demonstrated that LUTS were highly prevalent in men above the age of 40 years and that the prevalence increased with age [7]. Like others, this study also found a predominance of storage symptoms over voiding and post-micturition symptoms [79]. However, the overall prevalence of LUTS, storage LUTS, and voiding LUTS were significantly lower than was reported by Kim et al [10] amongst Korean men.

In our study, the most common symptom was nocturia, defined as more than 1 nocturnal micturition per night, while straining and hesitancy were the least common symptoms. This agrees with the findings of some other researchers [1112] but differs from the findings of another Korean study, in which nocturia and weak stream were the most prevalent symptoms, but urgency was the least prevalent symptom [13].

The healthcare-seeking attitude and behavior of patients are important determinants of the outcomes of the disease process. This has been shown to be a major contribution to racial discrepancies worldwide due to socio-cultural factors and differences in the perception of aetiologies and treatment of diseases [14]. Of the 389 men with LUTS in this study, slightly more than half of them had ever sought help from either traditional or orthodox medical practitioners. Almost half (46.8%) had never sought help. This is similar to the results of a study of elderly men with prostatic symptoms in Korea [15], in which 42.7% of men never sought help. The percentage of men with LUTS who sought medical help in the UK and USA were significantly higher than was reported in this study, suggesting that socio-cultural differences may be relevant. A study in Michigan that clearly documented that more white men sought medical help than their black counterparts provides further support this assertion regarding socio-cultural differences and beliefs [16].

In this study, 87.9% of those with a severe IPSS score sought help, compared to 59.1% and 38.7% of those with moderate and mild symptoms, respectively. This suggests the possibility that the bothersomeness of LUTS in this category of symptomatic men was the factor responsible for their more positive healthcare-seeking behavior.

The most common reasons for seeking healthcare were bothersomeness of the symptoms in approximately 58.8% of respondents, with symptoms and fear of one form of complication or the other in 37.1%. This agrees with the finding amongst community-dwelling men in Minnesota that severity and/or bothersomeness of the symptoms were the most important reason why LUTS/BPH patients sought help [1]. Other notable reasons for seeking healthcare in this study were fear of being diagnosed with cancer in 21.6%, as well as fear of embarrassment from urinary retention and the subsequent use of a urethral catheter in 9.3%. This is unlike the findings of a study in London, UK [17], that the fear of cancer was the most common reason for seeking help. It also differs from the findings of a study in Seoul, South Korea which documented unsatisfactory QoL to be the most common factor affecting healthcare-seeking behavior [18]. The other important reasons in their study were sleep disruption (25%) and discomfort (21.3%), but these reasons were not found to be major concerns for the participants in this study.

In this study, more than half (53.4%) of the subjects with LUTS relied on traditional treatment either alone or in conjunction with hospital care. This suggests that rural-dwelling people patronize traditional doctors to a considerable extent. This might be due to a deep-rooted belief in the efficacy of traditional treatment or the lack of available, affordable and accessible orthodox healthcare services in rural locations [19].

The reasons for not seeking medical care varied amongst individuals with LUTS. More than two-thirds (72%) of those who did not seek medical care believed that LUTS are an inevitable part of ageing process. Most men did not perceive LUTS as serious due to the gradual nature of the onset of symptoms, which they usually considered unimportant. They also did not consider it to be worrying even if the symptoms were bothersome. Similar results have been obtained from other community-based studies in other parts of the world [215]. A subjective feeling of wellness was the second most common reason (62.2%) why symptomatic participants did not seek help. This is not so surprising in our environment, as patients are notorious for late presentation for both benign and malignant diseases in sub-Saharan African countries, with resultant higher mortality and morbidity rates than observed in the rest of the world [202122]. Other important factors for not seeking medical care were financial difficulty, fear of surgery, and fear of being diagnosed with prostate cancer. Four subjects had no specific reason for not seeking healthcare. An average delay of approximately 18 months took place before these men reported their symptoms to healthcare providers. Improvements in the level of awareness as well as attitudes towards prostatic diseases will be necessary through public awareness programmes to shorten this period, with the goal of reducing the number of complications due to delayed presentation.

Several factors have been postulated to be responsible for poor healthcare-seeking attitudes or behaviors, ranging from socio-demographic to clinical factors. In this study, age was not a significant factor affecting the healthcare-seeking attitudes of participants. The perception of prostatic symptoms as part of the ageing process had a similar distribution amongst men of all age groups and did not influence decisions to seek help. The results of this study also showed that the healthcare-seeking behavior of the respondents increased with increasing educational status. All respondents with a tertiary education had visited a hospital to complain about their symptoms, while more than one-third of respondents without any formal education had not sought help for their condition. Not surprisingly, educational status was found to be a significant factor that determines healthcare-seeking behavior. The proportion of those who seek medical attention increases with increasing levels of education. Businessmen, civil servants, and retirees also had better attitudes and behavior than men in other occupations. On the contrary, marital status and religion were not found to be important factors determining healthcare-seeking behavior. Financial difficulties were found to affect care-seeking behavior adversely. This is not surprising as the level of poverty is still high in Nigeria and most of the healthcare services in the country are presently paid for out-of-pocket [2324]. The inclusion of BPH/LUTS in the coverage of the National Health Insurance Scheme will doubtlessly increase positive healthcare-seeking behavior.

The clinical factors that influenced healthcare-seeking behavior were the severity of symptoms, the QoL score, ED, and dysuria (p<0.005). The greater the symptom severity and the poorer the QoL score, the greater the tendency to seek medical care. This concurs with the findings of other researchers [225]. In contrast to a study in California [16], no significant difference existed in the behavior between respondents with predominantly storage and voiding symptoms in this study. Duration of symptoms was also found to affect healthcare-seeking behavior as a greater proportion of those with a longer duration of symptoms sought help. Men with the concomitant presence of ED were found to exhibit more positive healthcare-seeking behavior. The findings of this study suggest that coexisting ED is a very strong factor affecting the healthcare-seeking behavior in men with BPH (p<0.014). This is, however, not surprising, as erectile function is an important aspect of men's health. A study in Camden, New Jersey also reported a very high prevalence of coexisting BPH and ED (approximately 79% to 100% of treatment-seeking men) in comparison with men in the general population [26]. Finally, as haematuria is an alarming symptom, it is not surprising that a higher proportion of men with LUTS with associated haematuria sought help than their counterparts with LUTS who did not experience haematuria.

The results of this study showed that despite the high prevalence of LUTS in elderly men in Nigeria, only about half of these men actually sought medical attention, with a long average symptom duration before presentation due to erroneous perceptions of their symptoms. The reasons given by the participants in this study for not seeking medical assistance underscore the importance of genuine efforts to increase public awareness using the mass media, hospitals and religious institutions. Improved health education about LUTS amongst men may improve the healthcare-seeking behavior with resultant early presentation and reductions in the consequences of delayed presentation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the surgical resident doctors of the Federal Medical Centre, Ido Ekiti who helped tremendously in the data collection from the participants.

References

1. Jacobsen SJ, Guess HA, Panser L, Girman CJ, Chute CG, Oesterling JE, et al. A population-based study of health care-seeking behavior for treatment of urinary symptoms. The Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status among men. Arch Fam Med. 1993; 2:729–735. PMID: 8111497.

2. Hunter DJ, Berra-Unamuno A. Treatment-seeking behaviour and stated preferences for prostatectomy in Spanish men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Br J Urol. 1997; 79:742–748. PMID: 9158513.

3. Girman CJ, Jacobsen SJ, Tsukamoto T, Richard F, Garraway WM, Sagnier PP, et al. Health-related quality of life associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in four countries. Urology. 1998; 51:428–436. PMID: 9510348.

4. Sarma AV, Wei JT, Jacobson DJ, Dunn RL, Roberts RO, Girman CJ, et al. Comparison of lower urinary tract symptom severity and associated bother between community-dwelling black and white men: the Olmsted County study of urinary symptoms and health status and the flint men's health study. Urology. 2003; 61:1086–1091. PMID: 12809866.

5. Ladha A, Khan RS, Malik AA, Khan SF, Khan B, Khan IN, et al. The health seeking behaviour of elderly population in a poor-urban community of Karachi, Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009; 59:89–92. PMID: 19260571.

6. Tinuade O, Iyabo RA, Durotoye O. Health-care-seeking behaviour for childhood illnesses in a resource-poor setting. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010; 46:238–242. PMID: 20337870.

7. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, Reilly K, Kopp Z, Herschorn S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006; 50:1306–1314. discussion 1314-5. PMID: 17049716.

8. Boyle P, Robertson C, Mazzetta C, Keech M, Hobbs FD, Fourcade R, et al. The prevalence of male urinary incontinence in four centres: the UREPIK study. BJU Int. 2003; 92:943–947. PMID: 14632852.

9. Lee YS, Lee KS, Jung JH, Han DH, Oh SJ, Seo JT, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, and lower urinary tract symptoms: results of Korean EPIC study. World J Urol. 2011; 29:185–190. PMID: 19898824.

10. Kim TH, Han DH, Lee KS. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in Korean men aged 40 years or older: a population-based survey. Int Neurourol J. 2014; 18:126–132. PMID: 25279239.

11. Huh JS, Kim YJ, Kim SD. Prevalence of benign prostatic hyperplasia on Jeju Island: analysis from a cross-sectional community-based survey. World J Mens Health. 2012; 30:131–137. PMID: 23596600.

12. Cunningham-Burley S, Allbutt H, Garraway WM, Lee AJ, Russell EB. Perceptions of urinary symptoms and healthcare-seeking behaviour amongst men aged 40-79 years. Br J Gen Pract. 1996; 46:349–352. PMID: 8983253.

13. Lee E, Yoo KY, Kim Y, Shin Y, Lee C. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in Korean men in a community-based study. Eur Urol. 1998; 33:17–21. PMID: 9471036.

14. Sarma AV, Burke JP, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, St. Sauver J, Girman CJ, et al. Associations between diabetes and clinical markers of benign prostatic hyperplasia among community-dwelling Black and White men. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31:476–482. PMID: 18071006.

15. Lee EH, Chun KH, Lee Y. Benign prostatic hyperplasia in community-dwelling elderly in Korea. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2005; 35:1508–1513.

16. Sarma AV, Wallner L, Jacobsen SJ, Dunn RL, Wei JT. Health seeking behavior for lower urinary tract symptoms in black men. J Urol. 2008; 180:227–232. PMID: 18499182.

17. Emberton M, Marberger M, de la Rosette J. Understanding patient and physician perceptions of benign prostatic hyperplasia in Europe: the Prostate Research on Behaviour and Education (PROBE) Survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2008; 62:18–26. PMID: 18028388.

18. Kim HH, Kong KA, Lee HJ, Yoon H, Lee BE, Moon OR, et al. Relationship of socioeconomic factors with medical utilization for lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia in a South Korean community. J Prev Med Public Health. 2006; 39:141–148. PMID: 16615269.

19. Olapade-Olaopa EO, Onawola KA. Challenges for urology in sub-Saharan Africa in 2006. J Mens Health Gend. 2006; 3:109–116.

20. Opoku SY, Benwell M, Yarney J. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviour and breast cancer screening practices in Ghana, West Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2012; 11:28. PMID: 22514762.

21. Chijioke A, Makusidi AM, Rafiu MO. Factors influencing hemodialysis and outcome in severe acute renal failure from Ilorin, Nigeria. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012; 23:391–396. PMID: 22382247.

22. Williams DL, Tortu S, Thomson J. Factors associated with delays to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in women in a Louisiana urban safety net hospital. Women Health. 2010; 50:705–718. PMID: 21170814.

23. Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BS, Obikeze EN, Okoronkwo I, Ochonma OG, Onoka CA, et al. Investigating determinants of out-of-pocket spending and strategies for coping with payments for healthcare in southeast Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010; 10:67. PMID: 20233454.

24. Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Ichoku H, Uzochukwu B. Financing incidence analysis of household out-of-pocket spending for healthcare: getting more health for money in Nigeria. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014; 29:e174–e185. PMID: 23390079.

25. Stranne J, Damber JE, Fall M, Hammarsten J, Knutson T, Peeker R. One-third of the Swedish male population over 50 years of age suffers from lower urinary tract symptoms. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009; 43:199–205. PMID: 19347773.

26. Seftel AD, de la Rosette J, Birt J, Porter V, Zarotsky V, Viktrup L. Coexisting lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction: a systematic review of epidemiological data. Int J Clin Pract. 2013; 67:32–45. PMID: 23082930.

Fig. 1

Frequency of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Multiple responses possible; ASS: any storage symptom, AVS: any voiding symptom, APMS: any post-micturition symptom.

Table 1

Distribution of symptoms and severity according to the age range of participants

Table 2

Reasons for seeking healthcare or for not seeking healthcare

Table 3

Influence of socio-demographic characteristics on healthcare-seeking behavior

Table 4

Influence of clinical factorsand symptom characteristics on healthcare-seeking behavior

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download