1. Broderick GA, Kadioglu A, Bivalacqua TJ, Ghanem H, Nehra A, Shamloul R. Priapism: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management. J Sex Med. 2010; 7:476–500. PMID:

20092449.

2. Montague DK, Jarow J, Broderick GA, Dmochowski RR, Heaton JP, Lue TF, et al. Members of the Erectile Dysfunction Guideline Update Panel. Americal Urological Association. American Urological Association guideline on the management of priapism. J Urol. 2003; 170:1318–1324. PMID:

14501756.

3. Kulmala RV, Lehtonen TA, Tammela TL. Priapism, its incidence and seasonal distribution in Finland. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1995; 29:93–96. PMID:

7618054.

4. Roghmann F, Becker A, Sammon JD, Ouerghi M, Sun M, Sukumar S, et al. Incidence of priapism in emergency departments in the United States. J Urol. 2013; 190:1275–1280. PMID:

23583536.

5. Song PH, Moon KH. Priapism: current updates in clinical management. Korean J Urol. 2013; 54:816–823. PMID:

24363861.

6. Pohl J, Pott B, Kleinhans G. Priapism: a three-phase concept of management according to aetiology and prognosis. Br J Urol. 1986; 58:113–118. PMID:

3516294.

7. Emond AM, Holman R, Hayes RJ, Serjeant GR. Priapism and impotence in homozygous sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med. 1980; 140:1434–1437. PMID:

6159833.

8. Shaeer OK, Shaeer KZ, AbdelRahman IF, El-Haddad MS, Selim OM. Priapism as a result of chronic myeloid leukemia: case report, pathology, and review of the literature. J Sex Med. 2015; 12:827–834. PMID:

25630365.

9. Burnett AL, Sharlip ID. Standard operating procedures for priapism. J Sex Med. 2013; 10:180–194. PMID:

22462660.

10. Metawea B, El-Nashar AR, Gad-Allah A, Abdul-Wahab M, Shamloul R. Intracavernous papaverine/phentolamine-induced priapism can be accurately predicted with color Doppler ultrasonography. Urology. 2005; 66:858–860. PMID:

16230153.

11. Abujudeh H, Mirsky D. Traumatic high-flow priapism: treatment with super-selective micro-coil embolization. Emerg Radiol. 2005; 11:372–374. PMID:

16151866.

12. Hellstrom WJ, Derosa A, Lang E. The use of transcatheter superselective embolization to treat high flow priapism (arteriocavernosal fistula) caused by straddle injury. J Urol. 2007; 178:1059. PMID:

17644141.

13. Baba Y, Hayashi S, Ueno K, Nakajo M. Superselective arterial embolization for patients with high-flow priapism: results of follow-up for five or more years. Acta Radiol. 2007; 48:351–354. PMID:

17453510.

14. Hatzichristou D, Salpiggidis G, Hatzimouratidis K, Apostolidis A, Tzortzis V, Bekos A, et al. Management strategy for arterial priapism: therapeutic dilemmas. J Urol. 2002; 168:2074–2077. PMID:

12394712.

15. Ciampalini S, Savoca G, Buttazzi L, Gattuccio I, Mucelli FP, Bertolotto M, et al. High-flow priapism: treatment and long-term follow-up. Urology. 2002; 59:110–113. PMID:

11796291.

16. Suzuki K, Nishizawa S, Muraishi O, Fujita A, Hyodoh H, Tokue A. Post-traumatic high flow priapism: demonstrable findings of penile enhanced computed tomography. Int J Urol. 2001; 8:648–651. PMID:

11903696.

17. Kirkham AP, Illing RO, Minhas S, Minhas S, Allen C. MR imaging of nonmalignant penile lesions. Radiographics. 2008; 28:837–853. PMID:

18480487.

18. Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Inherited haemoglobin disorders: an increasing global health problem. Bull World Health Organ. 2001; 79:704–712. PMID:

11545326.

19. Levey HR, Segal RL, Bivalacqua TJ. Management of priapism: an update for clinicians. Ther Adv Urol. 2014; 6:230–244. PMID:

25435917.

20. Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Feasibility of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in a pharmacologic prevention program for recurrent priapism. J Sex Med. 2006; 3:1077–1084. PMID:

17100941.

21. Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Priapism: new concepts in medical and surgical management. Urol Clin North Am. 2011; 38:185–194. PMID:

21621085.

22. Ateyah A, Rahman El-Nashar A, Zohdy W, Arafa M, Saad El-Den H. Intracavernosal irrigation by cold saline as a simple method of treating iatrogenic prolonged erection. J Sex Med. 2005; 2:248–253. PMID:

16422893.

23. Huang YC, Harraz AM, Shindel AW, Lue TF. Evaluation and management of priapism: 2009 update. Nat Rev Urol. 2009; 6:262–271. PMID:

19424174.

24. Pryor J, Akkus E, Alter G, Jordan G, Lebret T, Levine L, et al. Priapism. J Sex Med. 2004; 1:116–120. PMID:

16422992.

25. Kovac JR, Mak SK, Garcia MM, Lue TF. A pathophysiology-based approach to the management of early priapism. Asian J Androl. 2013; 15:20–26. PMID:

23202699.

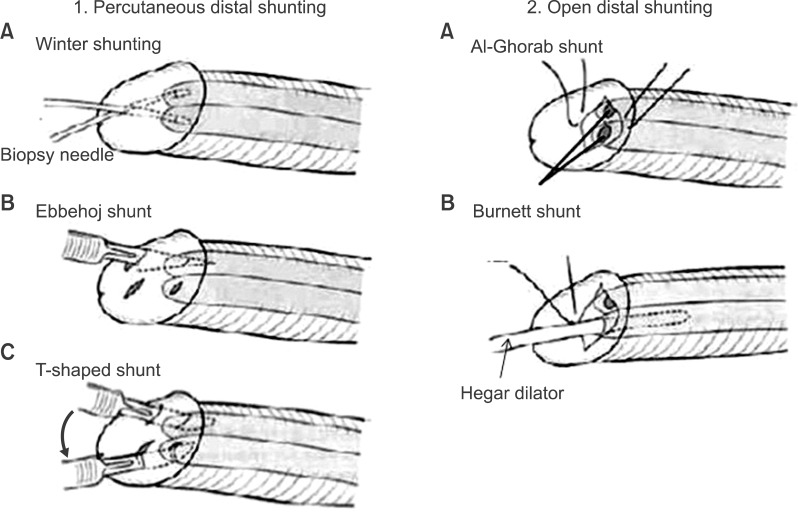

26. Winter CC. Cure of idiopathic priapism: new procedure for creating fistula between glans penis and corpora cavernosa. Urology. 1976; 8:389–391. PMID:

973296.

27. Ebbehoj J. A new operation for priapism. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974; 8:241–242. PMID:

4458048.

28. Brant WO, Garcia MM, Bella AJ, Chi T, Lue TF. T-shaped shunt and intracavernous tunneling for prolonged ischemic priapism. J Urol. 2009; 181:1699–1705. PMID:

19233430.

29. Nixon RG, O'Connor JL, Milam DF. Efficacy of shunt surgery for refractory low flow priapism: a report on the incidence of failed detumescence and erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2003; 170:883–886. PMID:

12913722.

30. Hanafy HM, Saad SM, El-Rifaie M, Al-Ghorab MM. Early arabian medicine: contribution to urology. Urology. 1976; 8:63–67. PMID:

781976.

31. Burnett AL, Pierorazio PM. Corporal "snake" maneuver: corporoglanular shunt surgical modification for ischemic priapism. J Sex Med. 2009; 6:1171–1176. PMID:

19207268.

32. Segal RL, Readal N, Pierorazio PM, Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ. Corporal Burnett "Snake" surgical maneuver for the treatment of ischemic priapism: long-term followup. J Urol. 2013; 189:1025–1029. PMID:

23017524.

33. Quackels R. Treatment of a case of priapism by cavernospongious anastomosis. Acta Urol Belg. 1964; 32:5–13. PMID:

14111379.

34. Grayhack JT, Mccullough W, O'conor VJ Jr, Trippel O. Venous bypass to control priapism. Invest Urol. 1964; 1:509–513. PMID:

14130594.

35. Rees RW, Kalsi J, Minhas S, Peters J, Kell P, Ralph DJ. The management of low-flow priapism with the immediate insertion of a penile prosthesis. BJU Int. 2002; 90:893–897. PMID:

12460352.

36. Cherian J, Rao AR, Thwaini A, Kapasi F, Shergill IS, Samman R. Medical and surgical management of priapism. Postgrad Med J. 2006; 82:89–94. PMID:

16461470.

37. Levey HR, Kutlu O, Bivalacqua TJ. Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature. Asian J Androl. 2012; 14:156–163. PMID:

22057380.

38. Burnett AL, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC, Musicki B. Long-term oral phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor therapy alleviates recurrent priapism. Urology. 2006; 67:1043–1048. PMID:

16698365.

39. Monga M, Broderick GA, Hellstrom WJ. Priapism in sickle cell disease: the case for early implantation of the penile prosthesis. Eur Urol. 1996; 30:54–59. PMID:

8854068.

40. Douglas L, Fletcher H, Serjeant GR. Penile prostheses in the management of impotence in sickle cell disease. Br J Urol. 1990; 65:533–535. PMID:

2354322.

41. Hakim LS, Kulaksizoglu H, Mulligan R, Greenfield A, Goldstein I. Evolving concepts in the diagnosis and treatment of arterial high flow priapism. J Urol. 1996; 155:541–548. PMID:

8558656.

42. Donaldson JF, Rees RW, Steinbrecher HA. Priapism in children: a comprehensive review and clinical guideline. J Pediatr Urol. 2014; 10:11–24. PMID:

24135215.

43. Steers WD, Selby JB Jr. Use of methylene blue and selective embolization of the pudendal artery for high flow priapism refractory to medical and surgical treatments. J Urol. 1991; 146:1361–1363. PMID:

1942293.

44. Cantasdemir M, Gulsen F, Solak S, Numan F. Posttraumatic high-flow priapism in children treated with autologous blood clot embolization: long-term results and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2011; 41:627–632. PMID:

21127852.

45. Wear JB Jr, Crummy AB, Munson BO. A new approach to the treatment of priapism. J Urol. 1977; 117:252–254. PMID:

833984.

46. Oztürk MH, Gümüş M, Dönmez H, Peynircioğlu B, Onal B, Dinç H. Materials in embolotherapy of high-flow priapism: results and long-term follow-up. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2009; 15:215–220. PMID:

19728271.

47. Savoca G, Pietropaolo F, Scieri F, Bertolotto M, Mucelli FP, Belgrano E. Sexual function after highly selective embolization of cavernous artery in patients with high flow priapism: long-term followup. J Urol. 2004; 172:644–647. PMID:

15247752.

48. Tønseth KA, Egge T, Kolbenstvedt A, Hedlund H. Evaluation of patients after treatment of arterial priapism with selective micro-embolization. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2006; 40:49–52. PMID:

16452056.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download