Abstract

Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma is a rare malignancy arising from the mesenchymal tissues of the spermatic cord, epididymis, testis, and testicular tunica, and accounts for approximately 7% of all rhabdomyosarcomas. It often occurs in children but is known to have a better prognosis than disease at other urogenital sites. Patients typically present with painless unilateral scrotal swelling like a solid testicular tumor. However, we report an unusual case of delayed diagnosis of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma accompanied by epididymitis manifesting an painful scrotal swelling.

Rhabdomyosarcoma is a malignant tumor resulting from the abnormal proliferation of rhabdomyoblasts, which can grow in any part of the body that contains embryonic mesenchyme. In general, rhabdomyosarcoma accounts for 5~10% of all childhood tumors and only 7% of all rhabdomyosarcomas are of paratesticular origin. In the Korean literature, only 4 cases of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma in chldren have been reported.1 We present an unusual case of delayed diagnosis of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma accompanied by epididymitis manifesting as painful scrotal swelling.

A 10-year-old boy presented to the outpatient department of urological services with painful swelling in the scrotum on the right side that had lasted for 2~3 days. The medical history of the patient was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a mild tenderness and erythema of the hemi-scrotum on the right side. Scrotal ultrasound at presentation reportedly demonstrated that the right epididymis showed massive swelling (4 cm×3 cm) with marked increased vascularity and suspicious for severe epididymitis with the need to diagnose the epididymal tumor like as adenomatoid tumor differentially. Therefore, the boy was discharged with antibiotics and instructions to follow up in case symptoms persisted. After 2 weeks, he returned to the outpatient department with persistent pain and swelling. He was hospitalized for further evaluation and an exploratory operation. Laboratory evaluation showed mild leukocytosis and normal lactate dehydrogenase, α-fetoprotein, and β-human chorionic gonadotropin. The surgical findings indicated that there was no abscess in the right scrotum but mild adhesion due to inflammation except hard epididymal mass. We conducted excisional biopy for the mass. The pathologist determined that although the tissue specimen was not large enough to confirm diagnosis, the hard mass was at least low grade sarcoma. Subsequently abdominopelvic computed tomography and chest radiography revealed no metastases. Magnetic resonance imaging of the testis showed a large epididymal mass (5 cm×4 cm×6 cm) on the right side was well-demarcated and heterogeneously enhanced (Fig. 1). The following week, the patient underwent right radical orchiectomy and hemiscrotectomy given tumor inavsion of the scrotal wall. Macroscopic examination showed that the large epididymal mass was an enlarged and well-demarcated yellow myxoid solid tumor (5.5 cm×4.5 cm) with hemorrhagic change and focal necrosis. Normal testicular tissue was expelled peripherally (Fig. 2). The tunica albuginea and testis had not been invaded by the tumor, and the surgical margin was also negative. Microscopic examination demonstrated a highly cellular tumor composed of rhabdomyoblasts and pleomorphic cells with ovoid hyperchromatic nuclei and containing eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3). As seen on an immunohistochemical stain, the tumor was diffusely and strongly positive for desmin and MyoD1. In conclusion, because there was no evidence of metastasis, the patient was classified into group I of the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS). He underwent 3 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy (VAC regimen: vincristine 1.5 mg/m2 on day 8 IV; dactinomycin 1.5 mg/m2 on day 8 IV; and cyclophosphamide 150 mg/m2 IM on day 1~7). At 1 year of follow-up, we found him to be disease free.

In the international classification of rhabdomyosarcoma there are 5 recognized variants: embryonal, alveolar, botryoid embryonal, spindle cell embryonal, and anaplastic.2 The most common variant is embryonal, which is most associated with tumors of the genitourinary tract and the head and neck. Histologically, the embryonal subtype resembles cells of a 6~8 week old embryo. A rhabdomyosarcoma can be identified with the use of desmin stains and muscle-specific actin stains, and more recently, myogenin. Scrotal rhabdomyosarcomas primarily originate from paratesticular tissues and occur predominantly in children and adolescents. Early diagnosis is critical given its aggressive nature and the relationship between the stage of the disease and survival. Patients typically present with painless unilateral scrotal swelling. In comparison, painful unilateral scrotal swelling usually leads to a diagnosis of epididymitis. As in this case, however, painful unilateral scrotal swelling has been described with paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma and the diagnosis should not be excluded.3 Unfortunately, we were neglectful of this point and did delay correct diagnosis. Scrotal sonography is the initial imaging modality of choice, but sonographic characteristics of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma are nonspecific. The identification of a mixed echogenicity hypervascular intrascrotal extratesticular mass is paramount. An associated hydrocele might be present but is more commonly seen with epididymitis like this case.4 Adenomatous tumors and leiomyomas are other solid extratesticular masses that occur with some frequency and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Metastases are typically via hematogenous or lymphatic routes and direct invasion of the testicular tunica.5 The most common sites of metastases from paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma are the regional lymph nodes, lungs, and cortical bone.5

The IRS group defines four clinical groups and four stages of disease that guide treatment and are directly related to prognosis.6 The clinical grouping is a surgical-pathological classification that categorizes patients into one of four groups based on the amount and extent of residual tumor after initial surgical procedures. The initial treatment for a rhabdomyosarcoma is inguinal orchiectomy. If there was previous trans-scrotal surgery or the tumor was fixed to the scrotal wall, it should be performed by inguinal orcihectomy and hemiscrotectomy including radical excision of the scrotal skin. Retroperitoneal node clearance is controversial and is probably not justified for staging or initial treatment; however, it has a role in debulking disease if positive nodes persist after chemotherapy. The role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy has not been fully determined. However, the tumor is definitely sensitive to both modes of treatment, and, certainly, adjuvant chemotherapy would now be considered mandatory even in tumors confined to the scrotum.7 In this case, the patient had undergone adjuvant chemotherapy that included vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide. On a recent follow-up study, no metastatic lesions were present after the adjuvant chemotherapy, even though we had not used radiotherapy. At the latest follow-up visit, the patient had been disease free for 1 year.

Once again, early identification of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma is critical. It should be a diagnostic consideration in patients presenting with unilateral scrotal swelling and should not be excluded on the basis of pain or hydrocele.3

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Magnetic resonance imaging for testis showed large epididymal mass (5 cm×4 cm×6 cm) on the right side was well-definedly demarcated and heterogenously enhanced. White arrow: epididiymal mass, white triangle: expelled testis.

Fig. 2

Macroscopic examination of testis showed that large epididymal mass was enlarged and well-demarcated yellow myxoid solid tumor (5.5×4.5 cm) with hemorrhagic change and focal necrosis. Normal testicular tissue was expelled peripherally. White arrows: epididiymal mass, white triangle: expelled testis.

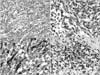

Fig. 3

Microscopic examination with H&E and immunohistochemical staining. (A) The tumor is composed predominantly of primitive ovoid cells with scattered rabdomyoblasts. The rhabdomyoblast in this case have eccentric vesicular nuclei and abundant densely eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E, ×200), (B) elongated rhabdomyoblasts with distinct cross-striations in eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E, ×400), (C) diffuse, strong positive immunoreactivity for desmin (desmin stain, ×400), (D) diffuse, strong positive immunoreactivity for MyoD1 (MyoD1 stain, ×400).

References

1. Kim DI, Kim KS. Two cases of pediatric paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma. Korean J Urol. 2004. 45:1072–1076.

2. Qualman S, Lynch J, Bridge J, Parham D, Teot L, Meyer W, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of anaplasia in childhood rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children's Oncology Group. Cancer. 2008. 113:3242–3247.

3. Aquino MR, Gibson DP, Bloom DA. Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma with metastatic encasement of the abdominal aorta. Pediatr Radiol. 2011. 41:1061–1064.

4. Mak CW, Chou CK, Su CC, Huan SK, Chang JM. Ultrasound diagnosis of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma. Br J Radiol. 2004. 77:250–252.

5. Akbar SA, Sayyed TA, Jafri SZ, Hasteh F, Neill JS. Multimodality imaging of paratesticular neoplasms and their rare mimics. Radiographics. 2003. 23:1461–1476.

6. Raney RB, Anderson JR, Barr FG, Donaldson SS, Pappo AS, Qualman SJ, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma in the first two decades of life: a selective review of intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study group experience and rationale for Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study V. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001. 23:215–220.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download