Abstract

Objective

This retrospective case series evaluated the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic cervical myomectomy.

Methods

Sixty-five patients with cervical myoma who underwent laparoscopic cervical myomectomy were included in this study.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 39.2 ± 6.0 years. The marriage rate was 67.7%, and the mean parity was 1.09. The most common symptoms in the patients were increased myoma size (41.5%) and menorrhagia (13.8%), while 20% of patients were asymptomatic. The average diameter of the myomas treated was 72.68 ± 20.28 mm, and the mean number of myomas per patient was 1.41 ± 0.88. Laparoscopic cervical myomectomy required a mean time of 63.25 ± 20.34 minutes. The difference between preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin levels was 2.01 ± 0.73 g/dL, and no patient required transfusion or conversion to laparotomy.

Conclusion

Sixty-five procedures of laparoscopic cervical myomectomy were performed safely. Operation time and complications were minimal. With correct understanding of pelvic anatomy, laparoscopic cervical myomectomy can be carried out safely and easily, and represents a minimally invasive treatment choice for symptomatic cervical myoma.

Uterine myoma is the most common benign tumor in women of reproductive age [1]. Leiomyoma affects 25% to 50% of women of reproductive age, and at least 50% of patients have significant symptoms [2]. Common symptoms of myoma include menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and pressure symptoms. The process of myoma development is not well understood and can continue until menopause. Indications for surgery include abnormal uterine bleeding, unresponsiveness to medical therapy, pain or pressure symptoms, urinary signs or symptoms, a high level of malignancy, growth after menopause, infertility with endometrial distortion, and recurrent pregnancy loss [1]. For preservation of fertility, myomectomy is carried out in women of reproductive age with symptomatic uterine myoma.

With the development of laparoscopic equipment and establishment of laparoscopic surgical settings, the indications for gynecologic laparoscopy have been extended. Nowadays, laparoscopic operation is generally preferred because of its good cosmetic results, reduced pain levels, short hospitalization time, quick recovery time, and similar outcomes as those of laparotomy [3]. Laparoscopic myomectomy is considered to be at the cutting-edge of minimally invasive surgery for patients who have symptomatic myoma.

Myomas are usually located on the uterine corpus, but 5% of myomas occur in the uterine cervix [4]. The uterine cervix is adjacent to the uterine arteries, ureters, rectum, and bladder. Therefore, cervical myomectomy has the surgical limitations of poor operative field, difficulties in suturing and handling of equipment, and vulnerability of the neighboring organs to injury. Thus, laparoscopic cervical myomectomy may be difficult and may be associated with a greater frequency of complications than other procedures [5].

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed data from 5 years of experience in performing laparoscopic cervical myomectomy.

From March 2007 to June 2011, 65 patients underwent laparoscopic cervical myomectomy at Cheil General Hospital. All patients had surgically proven cervical myoma, either preoperatively or during operation. All myomas were pathologically proved to be benign tumors. The medical records of these 65 patients who were treated in our department were retrospectively reviewed. If required, we also reviewed a video of the operation. Our selection criteria for laparopic myomecy are symptomatic fibroids under 12 cm sized in reproductive aged women and no more than four fibroids.

Data were collected on the general characteristics of the subjects; such as symptoms, age, body mass index, and parity. All patients were evaluated for fitness for general anesthesia. Preoperative gynecologic sonogram was underwent to record dimension, number and location of fibroids. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH) agonist was not used generally, but in the cases of severe anemia or other medical condition, we used GnRH agonist to delay the procedure. The operative time was defined as the time from umbilical incision to skin closure. To assess the changes of hemoglobin level after surgery, preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin levels were evaluated.

Data were analyzed with SPSS ver. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data are shown as mean standard deviation unless stated otherwise. A P-value of below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All operations were performed under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation. With the patient in the lithotomy position, a Rumi uterine manipulator was inserted. A vertical incision of approximately 10 mm was made in the infraumbilical skin, according to the standard technique. An 11-mm infraumbilical trocar was introduced into the abdominal cavity under laparoscopy; subsequently, the patient position was changed to the Trendelenburg position. After this, 2 lateral trocars and 1 suprapubic trocar were inserted. We used 10-mm, 30-degree fore-oblique telescopes in all procedures.

First, we inspected the pelvic and abdominal cavity, and if there were any other diseases present (e.g., endometriosis and adhesions), we operated on these lesions before myomectomy. Next, myoma number, location, and size were assessed.

Vasopressin was infiltrated subcapsularly to suppress bleeding during the operation. Up to 30 mL of vasopressin diluted to 10 IU in 100 mL of normal saline was injected into fibroids at several points. The myoma was then incised using monopolar scissors until the correct surgical plane was secured. After this, the incision was expanded until it was large enough to pull out the fibroids. Myoma enucleation was carried out with a suction tip and biopsy and Allis forceps. In most cases, a myoma screw was unnecessary.

Bleeding at the operative site was coagulated with bipolar electrocoagulation. If necessary, we sutured the myomectomy site with a continuous running suture using Vicryl 1-0 or tied it up using an endo-loop. After hemostasis was achieved, the right-hand side trocar was dilated to 15 mm, and a 15-mm trocar was inserted. The specimen was removed with an electric mechanical morcellator via the 15-mm trocar.

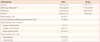

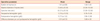

The baseline characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 39.2 ± 6.0 years. The marriage rate was 67.7%, and the mean parity was 1.09. Mean weight and body mass index were 56.85 ± 6.47 kg and 22.02 (2.61) kg/m2, respectively. GnRH agonist was used in 12 cases only once befor surgery. In 2 cases, GnRH agonist was used twice to correct severe anemia. 57% of cases had posterior cervical myoma, and 77.8 of myomas were subserosal type. The most common symptoms in the patients were increased myoma size (41.5%) and menorrhagia (13.8%) as listed in Table 2, while 20% of patients were asymptomatic. Fourteen patients were treated with preoperative GnRH agonists to reduce size of fibroids. Fifty-one patients (70%) received no preoperative management.

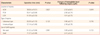

Table 3 demonstrated operative parameters of laparoscopic cervical myomectomy. The average diameter of the myomas treated was 72.68 ± 20.28 mm, and the mean number of myomas per patient was 1.41 ± 0.88. The largest diameter of myoma removed was 150 mm. The size of each myoma was assessed preoperatively by transvaginal ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging. In cases of multiple myomas, we defined a case of cervical myoma as the presence of the largest myoma on the cervix. Laparoscopic cervical myomectomy required a mean time of 63.25 ± 20.34 minutes, and considering the operation time reported in other studies, appeared not to require a greater time than that required for laparoscopic myomectomy. In all cases, morcellation was required to remove myomas from the pelvic cavity. The mean difference between preoperative and postoperative hemoglobin levels was 2.01 ± 0.73 g/dL, and no patient required transfusion or conversion to laparotomy. The mean hospital stay was 3 days from the day of operation. Discharge was allowed after confirming that patients could tolerate a normal diet.

Uterine geometry, such as location and type of myomas were not shown to affect the operative time and changes of hemoglobin levels following surgery. Use of GnRH agonist could not change that operative parameters, too (Table 4).

Pathologic results indicated leiomyoma in almost all cases, except for 2 patients. These 2 patients' pathologic reports indicated cellular leiomyoma and lipoleiomyoma. There were no cases of malignancy in any of the reports. Postoperative complications were minimal. No bladder or ureteral injury was reported, and there were no febrile complications (body temperature higher than 37.5℃). One case of pelvic infection occurred. A 41-year-old unmarried woman complained of whole abdominal pain with no febrile sense for several days after discharge from hospital. On the 21st postoperative day, she was admitted to hospital again and underwent re-operation. Pelvic inflammation and partial adhesion were seen at the previous myomectomy site, and the cul-desac was completely obliterated. Abscess removal and irrigation were performed via laparoscopy. After operation, the patient was administered antibiotics and discharged 9 days after re-operation with full recovery.

Laparoscopy is a feasible and safe method for the treatment of gynecologic disorders. The scope of laparoscopic gynecologic operation has been widened by the development of equipment and laparoscopic surgical settings. The first laparoscopic myomectomy was reported by Semm and Mettler [6], in 1979. With time, laparoscopic myomectomy has been developed. However, the 2000 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines stated that laparoscopic myomectomy was not recommended, primarily due to 2 major concerns over the benefits of laparoscopic myomectomy versus hysterectomy: the removal of large myomas through small abdominal incisions and repair of the uterus [7]. The introduction of more efficient morcellators has made removal easier, although the surgeon should be skilled in the operative technique to avoid injury to other organs. Although multiple techniques are available for laparoscopic suturing, it is controversial whether the closure techniques available are equal to those achieved at laparotomy.

However, more recent studies suggest that laparoscopic myomectomy can be a good alternative method to laparotomy for the treatment of myomas. Seracchioli et al. [8,9] reported less morbidity and faster recovery in the laparoscopy group in a randomized trial that compared the results of myomectomy performed using laparotomy and laparoscopy. The incidences of miscarriage, preterm labor, and uterine rupture were similar for laparoscopic myomectomy in several studies. Compared with laparotomic myomectomy, laparoscopic myomectomy has the advantages of good cosmetic results, less postoperative pain, short hospital stay, fast recovery, and additional assessment of the abdominopelvic cavity [3,10-12]. Nowadays, laparoscopic myomectomy is at the cutting edge of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery.

Many authors agree that careful preoperative selection is the most important factor for success of laparoscopic myomectomy. Several researchers have proposed criteria for laparoscopic myomectomy, but most of these are based solely on the subjects' own reports, which are not always reliable. Agdi and Tulandi [10]suggest the following criteria for laparoscopic myomectomy: a fibroid of <15 cm in size, and no more than 3 myomas with a size of 5 cm. In another study, Glasser [13] proposed other selection standards: uterine size ≤14 weeks after a 3-month course of GnRH agonist therapy, no individual myoma larger than 7 cm, no myoma located near the uterine artery or near the tubal ostia if fertility is desired, and presence of at least 50% subserosal myoma.

Marret et al. [14] stated the importance of the surgeon's experience. They suggested that the size of the largest myoma and the intramural type of the dominant myoma are important for predicting conversion rate, and also added a new risk factor: the surgeon's experience. Jung et al. [15] also emphasized the importance of experienced surgical team and laparoscopic surgeon.

One study suggests a risk estimation model for conversion to laparotomy. Dubuisson et al. [16] proposed 4 preoperative factors independently related to the risk of conversion: a size of 50 mm on ultrasonography, intramural type, anterior location, and preoperative use of GnRH agonists. Careful patient selection and expertise of the operating team are mandatory for success of laparoscopic myomectomy.

The site of the fibroid is a very important point for consideration, especially for laparoscopic procedures. Because of the proximity of cervical myomas to other organs and a poor visual field, the laparoscopic approach to a cervical myoma is difficult. The uterine cervix is very close to the uterine artery, ureters, rectum, and bladder. In most cases of cervical myoma, the operative field is not large enough to handle the myoma. Narrow visual field and proximity to other organs are important causes of laparoconversion during laparoscopic cervical myomectomy.

However, our experience indicates that this limitation can be circumvented by a good understanding of pelvic anatomy and expertise of the surgeon. In the current patient series, the ureters, uterine arteries, and rectum were separated before enucleation of fibroids when necessary. Generally, pedicular vessels were coagulated by bipolar electrocoagulation before removal of fibroids from myoma beds. Adequate separation of adjacent organs and proper coagulation of feeding vessels ensures that laparoscopic cervical myomectomy is an easy, fast, and bloodless process.

During laparoscopic cervical myomectomy, hemostasis is crucial for success. In our patients, intracorporeal suturing aided by vasopressin injection and bipolar coagulation was used for controlling bleeding during the procedure. Vasopressin, a vasoconstrictive agent used at a concentration of 10 IU in 100 mL of saline solution, was injected subcapsularly and at the base of the myoma before enucleation of fibroids. Bipolar coagulation with an electrocoagulator was used to control active bleeding, but we refrained from using it for excessive coagulation, especially in nulliparous women. Ligation of the uterine artery is commonly reported in other studies, but we did not use this technique routinely.

In most cases, the base of cervical myomas was sutured continuously. After enucleation of the myoma, a continuous running suture was performed as demonstratged in Fig. 1, if needed. In cases of intracervical myomas, we sutured the base of the myoma layer by layer and continuously. Fig. 2 showed operation of anterior intracervical myoma. Before enucleation, bladder flap was separated firstly and continuous suture was underwent layer by layer after myoma enucleation. In cervical myomectomy, suturing after enucleation is the most difficult part of the operation, because of the poor operative field and proximity of surrounding organs such as the bladder, ureters, and uterine arteries [17]. But these difficulties could be overcome with complete separation of adjacent organs before suturing.

Use of preoperative GnRH agonists was considered for reducing the size of myomas [18]. However, these agents were used in only 15 cases (23.1%) in our study. Several studies have evaluated the effect of preoperative treatment with GnRH agonists. Theoretically, preoperative treatment with a GnRH agonist should shrink the myoma and facilitate the operation. However, this treatment can actually increase the difficulty time required for the operation, because of alterations in the myoma tissue. In a systematic review that evaluated use of a GnRH agonist in laparoscopic myomectomy, no difference was found in operative time when GnRH agonist pretreatment was used; this review clarified the results of previous studies on the effect of GnRH agonist therapy. This meta-analysis did show a further reduction in intraoperative blood loss with GnRH pretreatment in patients undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy [18]. In the current report, use of GnRH agonists was restricted to cases of severe preoperative anemia and other medical conditions and use of that agent did not show any changes of operative results.

Laparoscopic myomectomy provides an acceptable and alternative method to laparotomy for women with symptomatic myomas who desire to maintain fertility. Compared to laparotomic myomectomy, laparoscopic myomectomy can provide rapid recovery and fewer adhesions. Advances in surgical equipment and operative skills have expanded the scope of laparoscopic myomectomy, although it still has some limitations. However, by using laparoscopy, the surgeon can secure a clear and broad view of the operation field and can also assess the peritoneal cavity. A good understanding of pelvic anatomy and sufficient training in laparoscopic myomectomy can ensure that this technique is a safe and fast procedure for treatment of cervical myomas. This procedure is also minimally invasive for the treatment of cervical myoma, regardless of number, size, and location. The current report is limited by a small sample size and loss of patients during follow-up. A larger scale study is required to better determine the guidelines for laparoscopic cervical myomectomy.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Laparoscopic cervical myomectomy: posterior cervical myoma, subserosal type. Before enucleation of myoma, ureter dissection was perfomed. After enucleation, incised peritoneum was sutured continuously.

Fig. 2

Laparoscopic cervical myomectomy: anterior cervical myoma, intracervical type. Adequate separation of the bladder was performed before myoma enucleation. In this case, the anterior cervix was incised to remove the myoma. After enucleation of the myoma, the incised cervix was sutured continuously in 2 layers.

References

1. Adams Hillard PJ. Berek JS, Novak E, editors. Benign diseases of the female reproductive tract. Berek & Novak's gynecology. 2007. 14th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;469–481.

2. Istre O. Management of symptomatic fibroids: conservative surgical treatment modalities other than abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008. 22:735–747.

3. Hurst BS, Matthews ML, Marshburn PB. Laparoscopic myomectomy for symptomatic uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2005. 83:1–23.

4. Stovall TG. Mann WJ, Stovall TG, editors. Myomectomy. Gynecologic surgery. 1996. New York (NY): Churchill Livingstones;445–461.

5. Takeuchi H, Kitade M, Kikuchi I, Shimanuki H, Kumakiri J, Kobayashi Y, et al. A new enucleation method for cervical myoma via laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006. 13:334–336.

6. Semm K, Mettler L. Technical progress in pelvic surgery via operative laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980. 138:121–127.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Clinical Management Guidelines for the Obstetrician-Gynecologist. Surgical alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. 2004 Compendium of Selected Publications. 2004. Washington, DC: ACOG;665–673. Number 16, May 2000.

8. Seracchioli R, Rossi S, Govoni F, Rossi E, Venturoli S, Bulletti C, et al. Fertility and obstetric outcome after laparoscopic myomectomy of large myomata: a randomized comparison with abdominal myomectomy. Hum Reprod. 2000. 15:2663–2668.

9. Seracchioli R, Manuzzi L, Vianello F, Gualerzi B, Savelli L, Paradisi R, et al. Obstetric and delivery outcome of pregnancies achieved after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 2006. 86:159–165.

10. Agdi M, Tulandi T. Endoscopic management of uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008. 22:707–716.

11. Dubuisso JB, Fauconnier A, Babaki-Fard K, Chapron C. Laparoscopic myomectomy: a current view. Hum Reprod Update. 2000. 6:588–594.

12. Lee CL, Wang CJ. Laparoscopic myomectomy. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009. 48:335–341.

13. Glasser MH. Minilaparotomy myomectomy: a minimally invasive alternative for the large fibroid uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005. 12:275–283.

14. Marret H, Chevillot M, Giraudeau B. Study Group of the French Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (Ouest Division). Factors influencing laparoconversions during the learning curve of laparoscopic myomectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006. 85:324–329.

15. Jung US, Wie HJ, Yoon HJ, Kyung MS, Lee KW, Han JS, et al. Clinical efficacy of laparoscopic myomectomy for 110 cases of various sized myomas. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 50:918–925.

16. Dubuisson JB, Fauconnier A, Fourchotte V, Babaki-Fard K, Coste J, Chapron C. Laparoscopic myomectomy: predicting the risk of conversion to an open procedure. Hum Reprod. 2001. 16:1726–1731.

17. Matsuoka S, Kikuchi I, Kitade M, Kumakiri J, Kuroda K, Tokita S, et al. Strategy for laparoscopic cervical myomectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010. 17:301–305.

18. Chen I, Motan T, Kiddoo D. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in laparoscopic myomectomy: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011. 18:303–309.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download