Abstract

Mycobacterium infection manifesting pyometra in postmenopausal women is a extremely rare disease that hardly responds to the usual treatment of pus drainage and antibiotics therapy. We present a case of a postmenopausal woman with pyometra caused by endometrial tuberculosis. Almost all of the pus could be drained through the stenotic cervical canal, with difficultly. The result of Pipelle endometrial biopsy was negative. However, her symptoms continued and fluid gradually re-accumulated in the uterine cavity, despite successful pus drainage and sufficient antibiotics use. Therefore, the endometrial tissue was obtained by fractional curettage after cervical dilatation to identify the accurate cause of pyometra. A pathologic examination and polymerase chain reaction confirmed the diagnosis of endometrial tuberculosis. After completion of antituberculous medication, she was doing well without further development of pyometra. In a case of postmenopausal pyometra, endometrial sampling should be performed to rule out endometrial tuberculosis.

Pyometra, an accumulation of pus in the uterine cavity, is an uncommon condition that has a reported incidence of 0.01%-0.5% in gynecologic patients [1]. Apart from its association with malignant disease, spontaneous rupture of pyometra can result in significant morbidity and mortality. If pyometra is diagnosed before rupture, dilatation of the cervix and drainage of pus is the treatment of choice. The most common organisms isolated through the bacteriologic study are Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis [2]. Endometrial tuberculosis (TB) with pyometra in postmenopausal women is extremly rare. We present a case of a postmenopausal woman with pyometra-continued symptoms, in spite of with pus drainage and empirical antibiotic therapy. However, she was cured completely with antituberculous medication after endometrial TB was confirmed in the endometrial sampling by fractional curettage.

A 77-year-old woman, who presented with vague lower abdominal pain over a period of two months, was admitted to our hospital. She had menopause at age 50 and had never taken hormone replacement therapy. In her and her family's medical histories, there were no medical problems such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or TB.

When the pelvic examination was performed, she did not show any symptoms, such as sharp tenderness of the abdomen, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, or uterine bleeding, except an atrophic lesion with desquamation of the vaginal introitus and posterior fourchette area.

Her Pap test result was normal, although she had never had one before. A transvaginal ultrasonogram revealed a dilated, fluid-filled endometrial cavity (Fig. 1A). Contrast-enhanced abdominal computerized tomography (CT) showed a collection of fluid in the dilated uterine cavity, without any suspicious malignant lesions (Fig. 1B). Under the guidance of thin sound, drainage of yellowish mucoid fluid was done successfully. Pipelle endometrial sampling was done. But, it could not be easily applied to the patient because of severe cervical stenosis at the time. There were just a few gram negative rods in Gram stain, and no specific bacteria grew in the culture of vaginal discharge. Pathologically, endometrial biopsy was negative. The basic laboratory tests screening, including a complete blood count, serum electrolytes, hepatic function tests, urinalysis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody test, thyroid function test, and electrocardiogram, were normal. A chest X-ray and high resolution CT of her thorax showed calcified pleural thickening in the upper right lung field that was suspected to be a granulomatous scarring.

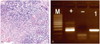

The patient's symptom continued and pus gradually re-accumulated in the uterine cavity, although the empirical antibiotic therapy for usual bacterial endometritis had been used for two weeks. Therefore, fractional curettage was performed to identify the underlying cause after cervical dilatation with thick sound under anesthesia. Histologically, endometrial tissue showed typical granulomatous inflammation with necrosis. Epithelioid cells formed granuloma and mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltrated around granuloma. Langerhans' giant cells were frequently recognized (Fig. 2A). No acid-fast bacilli were identified. The result of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was positive in the endometrial tissue samplings (Fig. 2B). Antituberculous treatment with a regimen of isoniazide (300 mg/day per oral), rifampicin (450 mg/day per oral), and ethambutol (800 mg/day per oral) was started for six months after the confirmative diagnosis. When the patient visited our clinic after completion of the antituberculous medication, she was doing well and no longer displayed any symptoms of pyometra.

Pyometra is a collection of purulent fluid within the uterine cavity. Cervical stenosis most frequently involves the internal os. The acquired causes of cervical stenosis include infection, neoplasia, and iatrogenic factors (radiation therapy or surgery) [1]. Pyometra is an uncommon, but important gynecologic condition, because the incidence of the association with malignant disease is considerable, and spontaneous rupture can result in significant morbidity and mortality. Dilatation of the cervix and pus drainage is the treatment of choice, and it is important to rule out the possibility of cancer and differentiate the malignancy.

Tuberculosis is a chronic infectious disease and still a serious health problem worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, it is estimated that about 8 million people develop active TB, with 1.6 million dying of TB each year [3]. Over 95% of new TB cases and deaths occur in developing countries with the main brunt being born in Africa and Asia, mainly due to coinfection with HIV infection and multidrug resistant-TB, including extensively drug resistant-TB [3,4]. Tuberculosis primarily affects the lungs, but about one-third of the patients also have involvement of extrapulmonary organs such as the meninges, bones, skin, joints, genitourinary tract, and abdominal cavity.

In genital TB, female genital TB begins in the endosalpinx and can spread to the peritoneum, endometrium, ovaries, cervix, and vagina [5]. The endometrium and ovary are affected in 50%-60% and 20%-30% of all cases of genital TB, respectively. In postmenopausal women, endometrial TB mainly occurs with postmenopausal bleeding. Mycobacterium infection of the genital tract, manifesting pyometra in postmenopausal women, is extremely rare. The reason of low incidence of endometrial TB in the postmenopausal women is not well known, but may be attributed to atrophic endometrium which has poor vascular support for Mycobacterium to grow [6].

The diagnosis of genital TB is difficult. Genital TB often goes undiagnosed because it is either asymptomatic, or occurs with non-specific symptoms, such as intermittent lower abdominal discomfort and abnormal vaginal discharge in most affected women. The Mantoux test may show a specificity of 80% and sensitivity of 55% in diagnosis of female genital TB [7]. The white blood cell count, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be raised in genital TB patients. Although an imaging study is not usually a confirmative diagnostic technique, an ultrasound of the pelvis may be helpful to demonstrate evidence of endometrial thickening or pyometra, as well as ascites and pelvic mass, in case of significant peritoneal disease.

A chest X-ray is normal in most cases, and may be necessary in an attempt to identify the possibility of a primary pulmonary focus, because genital TB is usually caused by the reactivation of an organism from systemic distribution of pulmonary TB.

The typical feature of tuberculosis on histology is a caseating granuloma with or without Langerhans' cells. Molecular biological testing by PCR aids in the presumptive diagnosis of endometrial TB [7]. Definitive diagnosis is the detection of tuberculosis bacilli in endometrial specimen cultures. Because there is a false negative rate of approximately 10%, a negative endometrial biopsy in a symptomatic patient must be followed by a fractional curettage under anesthesia.

Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of TB, even if it is pulmonary TB or extrapulmonary TB, are vitally important to reduce disease and treatment-related morbidity, and even mortality, in extreme cases. A six- to nine-month regimen (two months of isoniazid [INH], rifampin [Rifadin], pyrazinamide, and ethambutol [Myambutol], followed by four to seven months of isoniazid and rifampin) is recommended as initial therapy for all forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis unless the organisms are known or strongly suspected to be resistant to the first-line drugs [8]. If there is persistence of pelvic mass or recurrence of pyometra after six months of medical therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. In a case of postmenopausal pyometra-especially if it doesn't response to the empirical antibiotics therapy for usual endometritis-endometrial sampling should be performed to rule out endometrial tuberculosis.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Chan LY, Lau TK, Wong SF, Yuen PM. Pyometra. What is its clinical significance? J Reprod Med. 2001. 46:952–956.

2. Chan LY, Lam MH, Yuen PM. Sonographic appearance of Mycobacterium pyometra mimicking carcinoma of uterine corpus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005. 84:1124–1125.

3. Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, Gupta N, Jain SK, Malhotra N, et al. Genital tuberculosis: an important cause of Asherman's syndrome in India. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008. 277:37–41.

4. Güngördük K, Ulker V, Sahbaz A, Ark C, Tekirdag AI. Postmenopausal tuberculosis endometritis. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 2007:27028.

5. Simon HB, Weinstein AJ, Pasternak MS, Swartz MN, Kunz LJ. Genitourinary tuberculosis. Clinical features in a general hospital population. Am J Med. 1977. 63:410–420.

6. Maestre MA, Manzano CD, López RM. Postmenopausal endometrial tuberculosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004. 86:405–406.

7. Gatongi DK, Kay V. Endometrial tuberculosis presenting with postmenopausal pyometra. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005. 25:518–520.

8. American Thoracic Society. CDC. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003. 52:1–77.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download