Abstract

Congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS) is caused when the upper airway is obstructed or severely narrowed. The prenatal ultrasound findings of CHAOS include large echogenic lungs, inverted diaphragms, dilated airways, and fetal ascites and/or hydrops. Recently, exutero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure or fetoscopic tracheostomy are being widely used for the treatment of CHAOS. However, CHAOS with early presentation of hydrops confers ominous sign even with EXIT procedure. We report a case of CHAOS with hydrops and associated anomalies that was confirmed by autopsy.

An obstruction of the fetal upper airway in utero due to various reasons may cause a fatal condition - congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS). The prenatal ultrasound findings of CHAOS include large echogenic lungs, flattened or inverted diaphragms, dilated airways distal to the obstruction, and fetal ascites and/or hydrops [1]. If it is associated with severe hydrops and/or associated anomalies, its prognosis is fatal. Here we present a case of antenatally diagnosed CHAOS with associated anomalies and a literature review.

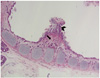

A 29-year-old woman (gravida 1, para 0) was referred to the Asan Medical Center at 20+5 weeks of gestation for evaluation of a fetal lung mass. Her menstruation had been on a regular cycle of 28-30 days. Her medical and familial medical history was unremarkable. Amniocentesis had already been performed before the referral because of fetal hydrops and a normal fetal chromosome was confirmed. A high resolution ultrasound examination was carried out at the Asan Medical Center. At the ultrasound examination, fetal weight was estimated at 542 g and the amount of amniotic fluid was normal. An ultrasound examination showed bilateral, expanded, hyperechoic lung, inverted diaphragm, anterior displacement of the heart, a visible trachea, massive ascites, pleural and pericardial effusion, and generalized edema (Fig. 1). These findings were strongly suggestive of CHAOS with fetal hydrops. The patient and her husband were counseled about the natural history and prognosis of CHAOS. They decided to terminate the pregnancy. The patient was transferred to Haeundae Paik Hospital near her house three days later. Labor was induced with laminaria and intravenous sulprostone. The patient delivered vaginally a breech-presented fetal body at 6 pm and a fetal head disconnected from the body came out immediately thereafter. An autopsy was performed to establish causes of the upper airway obstruction. A postmortem finding of a fetus that weighed 451 g was consistent with CHAOS. The fetus had a total blockage of the trachea due to thickened tracheal cartilage and soft tissue, herniation of brain and spinal cord into the dilated upper trachea, massively enlarged lungs bilaterally, flattened diaphragm, soft tissue edema of the trunk, and a compressed, relatively small heart (Fig. 2). There were micrognathia and a left 3rd toe that over-rode the 2nd toe. On microscopic examination, increased proliferation of fibroblasts in the tracheal cartilage and soft tissue was found (Fig. 3). Two days later, the patient was discharged uneventfully.

CHAOS is caused by complete obstruction or severe narrowing of the upper airway. Causes of obstruction are laryngeal atresia, subglottic stenosis, laryngeal web, a completely occluding laryngeal cyst, or, rarely, a tracheal obstruction. Complete or near complete obstruction of the upper airway in utero causes retension of fetal lung fluid and increases in intratracheal pressure. Massive distension of lung by intratracheal pressure results in cardiac and caval compression and subsequent heart failure, ascites, pleural effusion and hydrops in utero [2]. The true incidence of CHAOS is unknown because this is a very rare and life-threatening condition with high mortality and morbidity. Survival is dependent on early prenatal diagnosis, close prenatal follow up, and fetal or immediate postnatal intervention. If unrecognized before delivery, the reported mortality is 80% to 100%. In 1994, Hedrick et al. [1] first described the constellation of findings of CHAOS: large echogenic lungs, flattened or inverted diaphragms, dilated airways distal to the obstruction, and fetal ascites and/or hydrops. Advancements in ultrasound technology and introduction of fetal magnetic resonance imaging can provide visualization and localization of the level of the obstruction [3].

We present a case of CHAOS caused by complete tracheal obstruction. We found increased proliferation of fibroblasts in the tracheal cartilage and the soft tissue around the cartilage. The estimated abdominal circumference by ultrasound was 27 cm (which is normal for 31+3 gestational weeks) because of fetal ascites and generalized edema, whereas the estimated fetal biparietal diameter was 5.7 cm (normal for 22 gestational weeks). There was no abnormal finding regarding the fetal head at the prenatal ultrasound examination. Therefore, at the time of vaginal delivery of the breech-presented fetus, brain herniation and separation of the fetal head from the body may have occurred by traction of the fetus for delivery of the fetal abdomen trapped tightly in the uterine cervix.

CHAOS might be associated with other structural abnormalities. In the case presented, the fetus with CHAOS was accompanied by micrognathia and abnormalities of the toes. When CHAOS is diagnosed with the presence of severe associated abnormalities, a fatality is even more likely. A notable example of disease with upper airway obstruction with associated anomalies is Fraser syndrome. Fraser syndrome is characterized by variable defects including laryngeal atresia, cryptophthalmos, renal agenesis, syndactyly and genital abnormalities. Fraser syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder - the recurrence rate among siblings is 25%. A high maternal serum alphafetoprotein level may increase the suspicion of Fraser syndrome [4,5]. Laryngopharyngeal/pharyngotracheal pinpoint fistula on the obstructed portion or tracheoesophageal fistula may allow communication of lung fluid and release of increased intrathoracic pressure. Patients with pinpoint fistulas often do not have severe hydrops in utero [6]. Isolated airway obstruction without hydrops has a relatively favorable prognosis. CHAOS with early presentation of hydrops is an ominous sign with a high rate of fetal demise and a poor survival rate even with the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure.

Roybal et al. [7] reported the prognosis and severity of twelve cases of CHAOS. According to their study, there was no evidence of fetal hydrops in four of the five cases whose EXIT procedures were successful. The number of fetuses who had fetal hydrops was eight, and only one fetus among the eight survived for more than one year.

The EXIT procedure for a various fetal conditions was first reported by Mychaliska et al. [8] in 1997. The first successful EXIT procedure for a case of CHAOS was reported by DeCou et al. [9] in 1998, and there have been many studies of EXIT for fetal airway obstructions. The EXIT procedure is performed using high doses of inhaled halogenated agents to facilitate uterine relaxation during cesarean section. The fetus remains hemodynamically stable, as the uteroplacental circulation is maintained. A variable strategy is attempted at intubation, including direct laryngoscopy, rigid bronchoscopy, and tracheostomy. And then the uteroplacental circulation is interruped [8]. In recent years, fetoscopic tracheoscopy has been performed to eliminate the cause of obstruction. It was possible to create a pharyngotracheal fistula for the decompression of the lung. However, further studies are necessary to determine the long term effects and safety of fetoscopic tracheoscopy [2,10].

In the case presented, the fetus with CHAOS not only had severe hydrops, but also had associated anomalies. We could not try the EXIT procedure or tracheoscopy in utero. This procedure requires cooperation of obstetricians, pediatric surgeons, anesthesiologists, and neonatologists. This report is a rare case of CHAOS with severe hydrops and associated anomalies in Korea. We hope this case report will encourage others to try to perform the EXIT procedure and other fetal treatments.

Figures and Tables

References

1. Hedrick MH, Ferro MM, Filly RA, Flake AW, Harrison MR, Adzick NS. Congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS): a potential for perinatal intervention. J Pediatr Surg. 1994. 29:271–274.

2. Lim FY, Crombleholme TM, Hedrick HL, Flake AW, Johnson MP, Howell LJ, et al. Congenital high airway obstruction syndrome: natural history and management. J Pediatr Surg. 2003. 38:940–945.

3. Courtier J, Poder L, Wang ZJ, Westphalen AC, Yeh BM, Coakley FV. Fetal tracheolaryngeal airway obstruction: prenatal evaluation by sonography and MRI. Pediatr Radiol. 2010. 40:1800–1805.

4. Kalpana Kumari MK, Kamath S, Mysorekar VV, Nandini G. Fraser syndrome. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2008. 51:228–229.

5. Eskander BS, Shehata BM. Fraser syndrome: a new case report with review of the literature. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2008. 27:99–104.

6. Kanamori Y, Kitano Y, Hashizume K, Sugiyama M, Tomonaga T, Takayasu H, et al. A case of laryngeal atresia (congenital high airway obstruction syndrome) with chromosome 5p deletion syndrome rescued by ex utero intrapartum treatment. J Pediatr Surg. 2004. 39:E25–E28.

7. Roybal JL, Liechty KW, Hedrick HL, Bebbington MW, Johnson MP, Coleman BG, et al. Predicting the severity of congenital high airway obstruction syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 2010. 45:1633–1639.

8. Mychaliska GB, Bealer JF, Graf JL, Rosen MA, Adzick NS, Harrison MR. Operating on placental support: the ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure. J Pediatr Surg. 1997. 32:227–230.

9. DeCou JM, Jones DC, Jacobs HD, Touloukian RJ. Successful ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure for congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS) owing to laryngeal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1998. 33:1563–1565.

10. Paek BW, Callen PW, Kitterman J, Feldstein VA, Farrell J, Harrison MR, et al. Successful fetal intervention for congenital high airway obstruction syndrome. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2002. 17:272–276.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download