Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association between outcomes of total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH) and patient demographic and clinical factors.

Methods

The present study was performed on a total of 1,041 women who underwent TLH, with or without bilateral/unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, from May 2003 to December 2008, excluding patients who also underwent other procedures simultaneously, including ovarian cystectomy, colporrhaphy, incontinence surgery, pelvic/para-aortic lymph node dissection, and/or omentectomy. The medical records were reviewed and clinical outcomes were analyzed.

Results

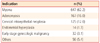

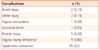

Mean patient age was 46.6 ± 13.4 years, mean operation time was 103.4 ± 42.3 minutes, and mean duration of total hospital stay was 5.4 ± 2.9 days. The mean decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before operation to 1 day after surgery was 1.4 ± 0.9 g/dL, and one patient required an intraoperative transfusion. The main diagnosis was leiomyoma including concomitant adenomyosis (62.2%), followed by adenomyosis (16.0%) and 32 early stage gynecologic malignancies including 20 patients with microinvasive cervical cancer, 10 with endometrial cancer, 1 with borderline ovarian cancer, and 1 with uterine sarcoma. Laparotomy conversion was occurred in 45 patients (4.2%), because of severe pelvic/abdominal adhesion or huge uterine size. Large uterine size was associated with a significantly higher rate of conversion (7.9% vs. 2.6%, P < 0.01), and a significantly longer operation time (110.5 minutes vs. 93.1 minutes vs. 95.3 minutes, P < 0.01). Overall, 6 patients (0.6%) experienced major complications, including two bowel perforations, two ureteral injuries requiring surgical repair, one vaginal evisceration, and one incisional hernia.

Hysterectomy is the most common operation in gynecology. For example, one-third of American women will have undergone a hysterectomy by age of 65 years [1], and 20% of women in the United Kingdom will have undergone a hysterectomy by age of 55 [2]. Several surgical techniques are currently utilized for hysterectomy, including total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), vaginal total hysterectomy, and total laparoscopic hysterectomy (TLH), with the proportion of patients treated with the latter operation increasing. In our institute, the proportion of TLH has increased from 59% in 2003 to 74% in 2008. This increase is attributable to the development of laparoscopic devices and the several advantages of laparoscopic surgery including shorter hospital stay; more rapid recovery; earlier return to normal activities; better cosmetic results; reduced postoperative pain/adhesion/wound infection/ileus; reduced intraoperative bleeding, more magnification of the pelvis; and facilitated access to the uterine vessels, ureter, rectum, and vagina [3-5]. Despite these advantages, however, laparoscopic surgery is not always feasible and may be contraindicated in women who have undergone repeated cesarean section or repeated open abdominal surgery, especially midline incision, those who cannot tolerate general anesthesia; and women with severe obesity (body mass index > 30 kg/m2) [6,7]. Nevertheless, even in such women, there is no absolute contraindication to laparoscopic surgery because these relative contraindications can be overcome by an expert surgeon.

In the present study, we evaluated the association between outcomes of TLH and patient demographic and clinical factors.

We reviewed the medical records of all the 1,389 patients who underwent TLH, with or without bilateral/unilateral salpingooophorectomy, at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between May 2003 and December 2008. We excluded 348 patients who underwent combined operations, including ovarian cystectomy, colporrhaphy, incontinence surgery, pelvic/para-aortic lymph node dissection, and omentectomy. Thus, our patient cohort consisted of 1,041 patients, all of whom were followed-up for more than 1 year postoperatively. Their medical records were reviewed and clinical outcomes were analyzed. Approval for the review of medical records was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

TLH was performed under general anesthesia, as described [8]. TLH outcomes were correlated with patient demographic features and clinical characteristics.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The chi-squared test and one-way analysis of variance were used for comparisons. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

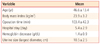

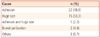

Mean patient age was 46.6 ± 13.4 years, mean operation time 103.4 ± 42.3 minutes, and mean duration of total hospital stay 5.4 ± 2.9 days. The mean decrease in hemoglobin concentration from before operation to 1 day after surgery was 1.4 ± 0.9 g/dL, and only one patient required an intraoperative transfusion. The mean uterine longitudinal diameter measured by transvaginal ultrasonography was 10.5 ± 2.5 cm (Table 1). The most common diagnosis in the women was leiomyoma, including concomitant adenomyosis (62.2%), followed by adenomyosis (16.0%), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN, 12%), endometrial hyperplasia (1.3%), and early-stage gynecologic malignancies, including 20 women with microinvasive cervical cancers, 10 with endometrial cancers, 1 with borderline ovarian cancer, and 1 with uterine sarcoma (Table 2). Other diagnoses included pelvic organ prolapse, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, transgender, and endometriosis. Overall, only six patients (0.6%) experienced major complications including two with bowel perforation, two with ureteral injuries requiring surgical repair, one with vaginal evisceration, and one with incisional hernia (Table 3). Forty-five women (4.2%) required conversions to laparotomy, because of severe pelvic/abdominal adhesion, large uterine size, intraoperative bowel perforation, inaccessible location of the myoma, or narrow posterior cul-de-sac (PCDS) (Table 4). The rate of laparotomy conversion was significantly higher in women with larger (> 11 cm in largest diameter, cutoff value determined by receiver operating characteristic curve) than smaller (≤11 cm) uteri (7.9% vs. 2.6%, P < 0.01) (Fig. 1). When we analyzed the operation time according to uterus size, we found that women with large (>10 cm) uteri required a significantly longer operation time than did those with small (<6 cm) or medium-sized (6-0 cm) uteri 93.1 ± 53.9 minutes for small uterus (<6 cm), 95.3 ± 30.6 minutes for medium-sized uterus (6-10 cm), and 110.5 ± 40.8 minutes for large uterus (>10 cm) (Fig. 2).

We assessed clinical outcomes relative to demographic and clinical characteristics in 1,041 women who underwent TLH. Overall, we found that TLH was a safe and acceptable alternative to standard hysterectomy for various indications, including malignancy, and that a large uterus may predict conversion to laparotomy and longer operation time for TLH.

TLH, first reported in 1984 [9], is hysterectomy performed entirely laparoscopically. In TLH, the ovarian and uterine arteries are secured, the vault is opened from above, the uterus is removed vaginally (or morcellated), and the vault is sutured, all laparoscopically [10]. Laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) differs from TLH in that LAVH is performed via a vaginal approach from uterine artery ligation. Common complications of TLH include injuries to the ureter, bladder, and bowel [3,8,11]. TLH has been performed in women with persistent or recurrent CIN, positive resection margins, or the presence of atypical glandular cells, as well as in women who request this type of surgery.

We found that the major complications associated with TLH were bowel injury, ureteral injury, vaginal evisceration, and incisional hernia, all of which required re-operation or referral to another department. However, the rate of major complications was minimal (0.6%), consistent with earlier findings [5]. Of the two patients with bowel injuries, the first experienced severe adhesion because of a previous myomectomy and was treated with resection and anastomosis of the small bowel, whereas the second patient had a previous history of cesarean section and appendectomy and was treated with anterior resection from the sigmoid colon to the rectum. Two women experienced ureteral injury, which presented as ureterovaginal fistulas. The first had endometriosis and was treated by implantation of an indwelling double J catheter for 2 months. Treatment of the second patient was more complicated; we first inserted a double J catheter and performed a percutaneous nephrostomy, but the distal portion of the left double J catheter was protruded into the vagina through a ureterovaginal fistula; we therefore performed a uretero-neocystostomy followed by a transureteroureterostomy. Vaginal evisceration occurred in one patient, who experienced abdominal pain after coitus 2 months after surgery. In this patient, the small bowel had protruded into the vagina. One patient experienced an incisional hernia at the left lower quadrant trocar site with omental hernia; this patient underwent a laparoscopic hernia repair. In addition, four patients experienced bladder injuries, which were repaired intraoperatively. These four patients had a previous history of cesarean section, myomectomy, tubal ligation, or pelviscopic salpingectomy due to ectopic pregnancy. Moreover, nine patients had vaginal stump dehiscence, which required resuturing 3-4 weeks, 2 months, or 4 months after surgery. The vault closure method was not associated with the incidence of stump dehiscence. Of all the 1,041 TLH cases, continuous interlocking suture was used in 366 patients and there were 4 cases of stump dehiscence (1.1%, 4/366). The rest 675 cases used interrupt figure of eight suture and had 5 cases of stump dehiscence (0.7%, 5/675). However, there was no significant difference between the two vault closure methods and the incidence of stump dehiscence.

Our rate of laparotomy conversions was 4.2%, similar to those reported elsewhere [12,13]. The main reasons were severe pelvic/abdominal adhesion, huge uterine size, and intraoperative bowel perforation. In addition, two patients required conversion because of inaccessible locations of myomas; one had a cervical myoma inaccessible via a laparoscopic approach and was converted to TAH, and the second had a myoma close to the lower segment that was difficult to dissect against the bladder. The procedure was converted to subtotal hysterectomy. One patient required laparotompic conversion because of narrow PCDS. In this patient, right ureteral injury was possible and the patient was therefore converted to TAH.

Surprisingly, no patient with a malignancy required conversion or experienced a major complication, suggesting that there is no contraindication to TLH in women with malignancy, when patients are properly selected.

In conclusion, our results confirm that TLH is a safe and acceptable alternative to standard hysterectomy for various indications, including malignancy. A large uterus may predict laparotomy conversion and longer operation time for TLH.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Relationship between uterus size and laparotomy conversion. AUC, area under the curve. aChi-squared test.

References

1. Marana R, Busacca M, Zupi E, Garcea N, Paparella P, Catalano GF. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999. 180:270–275.

2. Vessey MP, Villard-Mackintosh L, McPherson K, Coulter A, Yeates D. The epidemiology of hysterectomy: findings in a large cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992. 99:402–407.

3. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr L, Garry R. Methods of hysterectomy: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005. 330:1478.

4. Raju KS, Auld BJ. A randomised prospective study of laparoscopic vaginal hysterectomy versus abdominal hysterectomy each with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994. 101:1068–1071.

5. Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, Donnez J. A series of 3190 laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign disease from 1990 to 2006: evaluation of complications compared with vaginal and abdominal procedures. BJOG. 2009. 116:492–500.

6. Daraï , Soriano D, Kimata P, Laplace C, Lecuru F. Vaginal hysterectomy for enlarged uteri, with or without laparoscopic assistance: randomized study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001. 97:712–716.

7. Holub Z, Jabor A, Kliment L, Fischlová D, Wágnerová M. Laparoscopic hysterectomy in obese women: a clinical prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001. 98:77–82.

8. Elkington NM, Chou D. A review of total laparoscopic hysterectomy: role, techniques and complications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006. 18:380–384.

9. Semm K. Endoscopic methods in gastroenterology and gynecology. Completion of diagnostic pelviscopy by endoscopic abdominal surgery. Fortschr Med. 1984. 102:534–537.

10. Demco L, Garry R, Johns DA, Kovac SR, Lyons TL, Reich H. Hysterectomy. Panel discussion at the 22nd annual meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists (AAGL), San Francisco, November 12, 1993. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1994. 1:287–295.

11. Reich H. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: indications, techniques and outcomes. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007. 19:337–344.

12. Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, Hawe J, Napp V, Abbott J, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ. 2004. 328:129.

13. Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006. (2):CD003677.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download