Abstract

The incidence of cancer from adenomyosis is rare. Previously, only two cases of clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA) arising from adenomyosis have been reported in English literature. Here, we report a case of CCA arising from adenomyosis. A 52-year-old postmenopausal Korean woman presented with complaints of vaginal bleeding and back pain. Endometrial biopsy revealed endometrial polyp with atrophic change and transvaginal ultrasonography showed myomas with cystic change. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a cystic degenerative mass consistent with leiomyoma in the posterior portion of uterus body. And the serum level of CA-125 was 17.7 U/mL. Hysterectomy revealed a yellow-ten solid mass in the myometrium that was diagnosed as CCA arising from adenomyosis. The tumor was mainly located in the myometrium and transition between adenomyosis and CCA along with endometrial stromal cell was identified. Malignant tumor arising from adenomyosis could be considered as a differential diagnosis when the patient with adenomyosis and intact endometrial surface complained of vaginal bleeding.

The malignant transformation of patients with ovarian endometriosis has been reported approximately 0.7-1.0% [1]. On the other hand, the development of cancer from adenomyosis is a relatively rare occurrence. At present, only about 40 cases of malignant neoplasms arising from adenomyosis have been reported in English literature [2,3]. The most frequent histologic type of malignant neoplasm arising from adenomyosis is endometrioid adenocarcinoma. However, until recently, only 2 cases of clear cell carcinoma (CCA) arising from adenomyosis has been reported [2,4].

Here, we report additional one case of CCA arising from adenomyosis clinically mimicking smooth muscle tumor of myometrium.

A 52-year-old postmenopausal gravida 2 and para 2 Korean woman presented at the local hospital with complaints of vaginal bleeding and back pain. Her medical history was nonspecific except for antihypertensive therapy and surgery for breast fibroadenoma. She had received routine gynecologic check up, and had known the existence of myomas which had no change in size. She was performed endometrial biopsy, abdomen and pelvis computed tomography (CT) and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) expecting endometrial pathology. Only a endometrial polyp was found in the biopsy specimen.

She was referred to Samsung Medical Center with the impression of degenerative myoma without complete exclusion of malignancy by MRI. By pelvic examination, the uterus was goose-egg sized, and there was no bleeding from uterus. Transvaginal ultrasonography showed two 4 cm sized myomas with cystic change and thin endometrium.

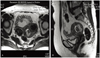

The serum level of CA-125 was 17.7 U/mL. MRI revealed a 3.4 cm intramural leiomyoma in the anterior portion of uterus body and a 3.3 cm cystic degenerative mass consistent with leiomyoma in the posterior portion of uterine body (Fig. 1). The cystic degenerative mass was not involved endometrium and no tumor was recognized in other organs.

Preoperative differential diagnoses included leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, endometrial carcinoma, or endometrial stromal sarcoma. We performed a laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy and frozen section revealed clear cell adenocacinoma. Laparoscopic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, paraaortic lymphadenectomy and total omentectomy were performed as surgical staging. There was no evidence of gross dissemination. Macroscopically, the resected uterus weighed 100 g (10 × 7 cm). Cross-section of the posterior uterine wall revealed an yellow-ten solid mass, measuring 4 × 3 cm in the myometrium with pushing the endometrium (Fig. 2A). The mass was mainly located in the myometrium that was clinically suspected as mesenchymal tumor, such as leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma, and endometrium was unremarkable. Microscopically, however, the tumor was CCA (Fig. 2B) and there was no connection between the myometrial mass and endometrium (Fig. 2C).

Interestingly periphery of the myometrial tumor showed numerous adenomyosis, which were intimacy related with tumor (Fig. 3A), and we identified that CCA arising from the adenomyosis (Fig. 3B). When we examined entirely endometrium, there was a focal isolated CCA in the endometrium (Fig. 3C).

The previous reported case with CCA arising from adenomyosis showed estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and p53 expression in the tumor. In our patient, the clear cell adenocarcinoma stained positively for ER, but did not express PR and p53 protein (Fig. 3D).

Based on these findings, this case was diagnosed as being CCA, grade III, arising from adenomyosis and classified as International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage Ib because of the invasion more than half of the myometrium. Postoperatively, whole pelvis radiotherapy (total dose of 5,040 cGy) was performed to prevent local recurrence because laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy had the possibility of tumor spillage and three cycles of systemic chemotherapy (paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and carboplatin 5 AUC) were performed.

The development of adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis have been rarely reported. And it is difficult to distinguish adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis from endometrial carcinoma arising from eutopic endometrium extend into preexisting adenomyosis [5]. In case of adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis, the following Sampson's or Colman's [6] criteria should be fulfilled to confirm the malignant transformation: 1) the carcinoma must not be located in the endometrium and elsewhere in the pelvis; 2) the carcinoma must be seen to arise from the epithelium of the adenomyosis and not to have invaded from another source; and 3) endometrial (adenomyotic) stromal cells must be present to support the diagnosis of adenomyosis. And Jacques and Lawrence [7] found a number of histologic features useful in identifying adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis, including a smooth, round contour of surrounding myometrium, adenomyotic glands and endometrial-type stroma within the carcinoma foci, and the absence of desmoplasia or an inflammatory response. Kumar and Anderson [8] emphasized the necessity of presence of the transition between the benign adenomyotic endometrial glands and the carcinomatous glands to prove the diagnosis of an ectopic endometrium-derived adenocarcinoma. In our case, although there was a focal isolated CCA in the endometrium, the diagnosis was compatible with CCA arising from adenomyosis because of the tumor being mainly located in the myometrium and identifying obvious transition between adenomyosis and CCA along with endometrial stromal cell.

Because of the rarity, the prognosis features of adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis are not well characterized. Niwa et al. [9] reported that patients with p53-overexpressing tumors also lacked ER or PR had a poor prognosis.

In summary, we report a case of clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis. Adenocarcinomas arising from adenomyosis are very rare and preoperative diagnosis is actually difficult. In some cases, carcinomas arising in adenomyosis may be associated with a delay in diagnosis, potentially resulting in a more advanced stage at presentation. The early diagnosis can be achieved by periodic follow-up using ultrasonography to detect any change in adenomyosis and if there is any change, MRI can be performed for further evaluation. Malignant tumor arising from adenomyosis could be considered as a differential diagnosis when the patient with adenomyosis and intact endometrial surface complained of vaginal bleeding.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

(A) Magnetic resonance imaging shows two uterine masses. (B) One of the uterine masses have a cystic degenerative change.

Fig. 2

(A) Yellowish round mass in the myometrium. (B) Microscopic findings of the mass show typical morphologies of clear cell carcinoma (H&E, ×400). (C) There is no connection between the mass and endometrium (H&E, ×100).

Fig. 3

(A) Periphery of the myometrial tumor shows numerous adenomyosis (arrows), which are intimacy related with tumor (H&E, ×200). (B) Clear cell carcinoma (arrows) arising from adenomyosis (H&E, ×200). (C)There is a focal isolated clear cell carcinoma in the endometrium (H&E, ×200). (D) The tumor is negative for p53 immunohistochemistry (Immunohistochemistry, ×200).

References

1. Irvin W, Pelkey T, Rice L, Andersen W. Endometrial stromal sarcoma of the vulva arising in extraovarian endometriosis: a case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1998. 71:313–316.

2. Koshiyama M, Suzuki A, Ozawa M, Fujita K, Sakakibara A, Kawamura M, et al. Adenocarcinomas arising from uterine adenomyosis: a report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002. 21:239–245.

3. Puppa G, Shozu M, Perin T, Nomura K, Gloghini A, Campagnutta E, et al. Small primary adenocarcinoma in adenomyosis with nodal metastasis: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2007. 7:103.

4. Hirabayashi K, Yasuda M, Kajiwara H, Nakamura N, Sato S, Nishijima Y, et al. Clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009. 28:262–266.

5. Motohara K, Tashiro H, Ohtake H, Saito F, Ohba T, Katabuchi H. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising in adenomyosis: elucidation by periodic magnetic resonance imaging evaluations. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008. 13:266–270.

6. Colman HI, Rosenthal AH. Carcinoma developing in areas of adenomyosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1959. 14:342–348.

7. Jacques SM, Lawrence WD. Endometrial adenocarcinoma with variable-level myometrial involvement limited to adenomyosis: a clinicopathologic study of 23 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1990. 37:401–407.

8. Kumar D, Anderson W. Malignancy in endometriosis interna. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1958. 65:435–437.

9. Niwa K, Murase T, Morishita S, Hashimoto M, Itoh N, Tamaya T. p53 overexpression and mutation in endometrial carcinoma: inverted relation with estrogen and progesterone receptor status. Cancer Detect Prev. 1999. 23:147–154.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download