Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to investigate the prognostic role of pre-treatment squamous cell carcinoma-related antigen (SCC-Ag) level in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix.

Methods

In this study, we retrospectively enrolled patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix (FIGO stage IB to IVA) who were treated at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea, from 1996 to 2007.

Results

We retrospectively enrolled 788 patients. Median SCC-Ag level was 1.6 ng/mL (reference range, 0.1-362.0) in all patients. Four hundred seven out of 788 patients had elevating pre-treatment SCC-Ag level (51.6%). When we divided the cohort based on the stage (early cervical carcinoma; IB1 and IIA vs. locally advanced cervical carcinoma [LACC]; IB2 and IIB to IVA) and performed multivariate analysis, pre-treatment SCC-Ag entailed prognostic significance only in LACC (progression-free survival: hazard ratio [HR], 1.007; 95% confidential interval [CI], 1.003-1.010; overall survival: HR, 1.005; 95% CI, 1.001-1.009). Among patients who showed recurrence disease and had the result of SCC-Ag before recurrence (n=94), 79 patients (84.0%) had the elevation of SCC-Ag level at the time of recurrence.

Cervical carcinoma is the third most common cancer in women, and the seventh overall, with an estimated 530,000 new cases in 2008 [1] and the one of the most lethal female malignancies in developing countries [2]. Cervical carcinoma can be categorized into subtypes according to histological classification, of which invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common, accounting for about 80% of invasive cancer in the cervix [3]. And other subtypes including adenocarcinoma of uterine cervix are considered as distinct disease entities against SCC from epidemiology to clinical manifestations [4].

Squamous cell carcinoma-related antigen (SCC-Ag), which also known as TA-4 (tumor antigen), may be the tumor marker of choice for SCC [5,6], not for the other types of carcinoma in uterine cervix. There was evidence of correlation between treatment response and SCC-Ag drops after treatment [7] and increasing serum SCC-Ag level can precede the clinical diagnosis of recurrent disease in 46-92% of the cases during the follow-up period after initial treatment [8], however, the clinical implementation in predicting prognosis based on pre-treatment serum SCC-Ag assay is still controversial [8,9].

The purpose of this study is to investigate the prognostic role of pre-treatment peripheral SCC-Ag level in patients with SCC of the cervix.

Patients with SCC of the cervix (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] stage IB to IVA) who were treated at Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea from 1996 to 2007 were retrospectively enrolled in this study. The patients' clinicopathological findings as well as laboratory results were collected from electronic medical records with Institutional Review Board approval. We excluded patients with early cervical cancer having microscopic lesions on the cervix including IA1 and IA2; histological subtypes except for SCC and its variants; patients who underwent fertility-saving surgery; patients with concurrent hematologic or infectious diseases; patients who did not have the results of SCC-Ag level within two weeks before starting initial treatment; and patients who received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy before surgery.

We usually performed surgery-based treatment in patients with early stage cervical cancer (IB1 to IIA), including bulky tumor (IB2) or radiation therapy (RT)-oriented management in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer (IIB to IVA). However, the choice for primary treatment was dependent on the attending physician's preference. Since 2000, concurrent chemotherapy with radiation therapy (CCRT) has been recommended as either the primary [10] or adjuvant treatment [11] in cases with more than one high-risk pathological factor for recurrence after surgery (please see below). Cisplatin-based regimens were used for the concurrent chemotherapy.

Standard surgery consisted of type III radical hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymph node (LN) dissection. Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and para-arotic LN sampling or dissections were not routine procedures. Patients who had more than one of the three high-risk factors (positive pelvic or para-aortic LN, microscopic parametrial invasion, and positive resection margins with tumor) received adjuvant RT or CCRT. Patients with at least two of the three intermediate risk factors (stromal invasion of more than half of the cervix or stromal invasion more than 1 cm, lympho-vascular space invasion, and the largest diameter of 4 cm or greater) received adjuvant RT alone. Radiation protocols were as previously described [12].

Patients had follow-up examinations approximately every three months for the first two years, every six months for the next three years, and every year thereafter. During the routine follow-up, imaging studies including computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, and chest X-ray was performed each year. When tumor recurrence was suspected based on clinical findings or imaging studies, biopsy was performed. We defined progression-free survival as the time from the initial treatment to relapse noted on images or to the final follow-up visit, and overall survival was defined as the time from the initial treatment to death due to cervical carcinoma or to the final follow-up visit.

The Wilcoxon rank sum test or two-sample t test was used to compare the median or mean values, respectively, after checking whether the data had non-normal or normal distributions according to the Shapiro-Wilks test. The overall and progression-free survival curves were calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Variables shown to be significant or borderline significant (P < 0.2) in the univariate analysis were selected for the Cox model. The Cox proportional-hazards model was used for the multivariate analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and all P-values were two-sided.

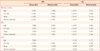

We retrospectively enrolled 788 patients with SCC of the cervix (IB to IVA). The basal characteristics of these patients are described in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 51 years (range, 21-85 years) and 407 out of 788 patients had elevating pre-treatment SCC-Ag level (51.6%). Median SCC-Ag level was 1.6 ng/mL (reference range, 0.1-362.0 ng/mL) in all patients. When the cohort was divided according to stage as either early cervical carcinoma (ECC) or locally advanced cervical carcinoma (LACC), patients with LACC had higher pre-treatment level of SCC-Ag (1.2 ng/mL vs. 7.1 ng/mL, P < 0.001). The median follow-up for the patient group was 53.4 months, with a range of 1-181 months, and the five-year survival rate was 87.8%. There were 121 progression (15.4%) and 88 (11.2%) cancer-related deaths during the study period.

In all patients, the univariate analysis revealed that the most of the clinical parameters including age, pre-treatment SCC-Ag level, stage, and type of treatment had prognostic significance for both progression-free survival and overall survival and these significances remained even after multivariate analysis except for age (Table 2). When we divided the cohort based on the stage (ECC: IB1 and IIA vs. LACC: IB2 and IIB to IVA) and performed multivariate analysis, pre-treatment SCC-Ag entailed prognostic significance only in LACC (progression-free survival: hazard ratio [HR], 1.007; 95% confidential interval [CI], 1.003-1.010; overall survival: HR, 1.005; 95% CI, 1.001-1.009). When we dichotomized the patients with LACC according the median level of pre-treatment SCC-Ag (7.1 ng/dL), the patients with LACC who had higher pre-treatment SCC-Ag level showed more than 2 times higher progression or death rate compared with patients who did not, in multivariate analysis (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Among patients who showed recurrence disease and had the result of SCC-Ag before recurrence (n=94), 79 patients (84.0%) had the elevation of SCC-Ag level with recurrence and the recurrence cases that showed pre-treatment SCC-Ag level more than 7.1 ng/dL represented increasing SCC-Ag level with recurrence in 100% (45/45) (Table 4).

In this study, we found that pre-treatment SCC-Ag level is an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with LACC. Most of the patients (84%, 79/94) had elevation of SCC-Ag level at the time of recurrent disease and SCC-Ag level increased again in all cases of recurrence, which showed high level of SCC-Ag (≥ 7.1 ng/dL) before the primary treatment (100%, 45/45).

Cervical carcinoma is the only major gynecologic malignancy that is staged clinically [13]. As a result predicting survival based on clinical stage alone may have limitation. For example, lymph node status, which is proven to be an important determinant of prognosis [14], is not part of the FIGO staging system. Furthermore, while we can use the post operative findings including lymph node status, parametrial invasion, and tumor present in resection margin to stratify the prognosis in early disease; the main treatment is surgery [3], there are no clinical parameters except for clinical stage in clinical staging system to stratify the prognosis of patients with advanced disease, which treatment is usually CCRT. This is why tumor marker in LACC should be so important in clinic and we could find that clinical impact of SCC-Ag on survival was bigger than that of clinical stage in our study population.

From the discovery [15] of SCC-Ag, which emerged concurrently with squamous formation of the uterine cervix and increased during the neoplastic transformation of the cervical squamous epithelium [6], several clinical researches investigated the prognostic role of SCC-Ag in squamous cell cervical carcinoma [8,16]. In ECC the prognostic role of SCC-Ag was not found in most of the studies [5,9,17,18], which is in line with our results. Even though there was evidence of a link between pre-treatment SCC-Ag level and lymph node metastasis in some studies [17,19], its prognostic significance is weak. Takeda et al. [19] reported that pre-operative SCC-Ag seems to be useful in estimating lymph node status and the prognosis for patients with cervical carcinoma. However, the study population was only 103, which was small, and about half of the patients were stage IIB, which is categorized into LACC with recommended management of RT or CCRT. Overall, routine check of serum SCC-Ag before surgery in ECC to predict recurrence may be unreasonable.

On the other hand, the prognostic role of pre-treatment SCC-Ag in LACC seems to be clear [7,20,21]. For example, Hong et al. [21] reported that pre-treatment SCC-Ag level higher than 10 ng/mL are an independent predictor for poor prognosis in their study of a single institution with large cohort, which is correspond well with our results. Furthermore we could observe that post-treatment follow-up SCC-Ag levels should be as important as measurement of pre-treatment level in LACC, especially in case of higher pretreatment SCC-Ag level (≥ 7.1 ng/dL), because all of the cases showed elevation of SCC-Ag level at the time of recurrent cervical carcinoma. However, it was also reported that pre-treatment SCC-Ag levels neither predicts pathological response to treatment nor the clinical outcome. Furthermore, they concluded that post-treatment SCC-Ag levels are more important to predict pathological response to CCRT and survival outcomes in LACC [22]. This debate should be confirmed in future studies.

There are some concerns should be discussed in this study. First, we do not have many treatment options to choose in LACC. Because CCRT was proven to be more effective than RT alone in LACC [10], CCRT is only standard treatment of choice in these patients. However, recently, it was reported that consolidation chemotherapy after CCRT may improve survival compared to CCRT alone in patients with LACC [12], which could give physicians a treatment option for patients with high level of pre-treatment SCC-Ag level. Second, other clinical parameters including paraaortic lymph node status on imagining study [23], patient's performance scale, or factors which could cause of elevated serum levels of SCC-Ag such as benign lesions of lung or skin diseases were not considered in this study [24]. Finally, many molecular markers have been investigated to predict prognosis of cervical carcinoma [25-27]. In the future, there should be a well designed prospective study to compare these molecular markers with SCC-Ag or develop prognostic models using combined index consist of these markers.

In conclusion, pre-treatment SCC-Ag level is an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with LACC. Measuring pre-treatment serum SCC-Ag may be a cost-effective method to predict prognosis in patients with LACC.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Progression-free survival and overall survival according to the squamous cell carcinoma-related antigen level (high vs. low) in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma.

Table 1

Patients' characteristics

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; SCC-Ag, squamous cell carcinoma-related antigen; ECC, early cervical cancer; LACC, locally advanced cervical cancer; RH, type III radical hysterectomy; RT, radiation therapy; CCRT, concurrent chemoradiation therapy.

aTA-4 (tumor antigen); bAdjuvant setting.

Table 2

Univariable and multivariable analysis for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS)

Table 3

SCC-Ag level as a prognostic factor for progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in locally advanced stages of cervical squamous cell carcinoma

References

1. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 10 [Internet]. 2010. cited 2011 Jul 20. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer;Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr.

2. Garcia M, Jemal A, Ward EM, Center MM, Hao Y, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer facts & figures 2007 [Internet]. 2007. cited 2008 Aug 22. Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society;Abailable from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/globalfactsandfigures2007rev2p.pdf.

3. Berek JS, Novak E. Berek & Novak's gynecology. 2007. 14th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

4. Gien LT, Beauchemin MC, Thomas G. Adenocarcinoma: a unique cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010. 116:140–146.

5. Davelaar EM, van de Lande J, von Mensdorff-Pouilly S, Blankenstein MA, Verheijen RH, Kenemans P. A combination of serum tumor markers identifies high-risk patients with early-stage squamous cervical cancer. Tumour Biol. 2008. 29:9–17.

6. Maruo T, Yoshida S, Samoto T, Tateiwa Y, Peng X, Takeuchi S, et al. Factors regulating SCC antigen expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Tumour Biol. 1998. 19:494–504.

7. Pras E, Willemse PH, Canrinus AA, de Bruijn HW, Sluiter WJ, ten Hoor KA, et al. Serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen and CYFRA 21-1 in cervical cancer treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002. 52:23–32.

8. Gadducci A, Tana R, Cosio S, Genazzani AR. The serum assay of tumour markers in the prognostic evaluation, treatment monitoring and follow-up of patients with cervical cancer: a review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008. 66:10–20.

9. Reesink-Peters N, van der Velden J, Ten Hoor KA, Boezen HM, de Vries EG, Schilthuis MS, et al. Preoperative serum squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels in clinical decision making for patients with early-stage cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 23:1455–1462.

10. Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, Thigpen JT, Deppe G, Maiman MA, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999. 340:1144–1153.

11. Peters WA 3rd, Liu PY, Barrett RJ 2nd, Stock RJ, Monk BJ, Berek JS, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2000. 18:1606–1613.

12. Choi CH, Lee YY, Kim MK, Kim TJ, Lee JW, Nam HR, et al. A Matched-Case Comparison to Explore the Role of Consolidation Chemotherapy After Concurrent Chemoradiation in Cervical Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010. 11. 13. [Epub]. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.07.2006.

13. Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009. 105:103–104.

14. Kidd EA, Siegel BA, Dehdashti F, Rader JS, Mutch DG, Powell MA, et al. Lymph node staging by positron emission tomography in cervical cancer: relationship to prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2010. 28:2108–2113.

15. Kato H, Torigoe T. Radioimmunoassay for tumor antigen of human cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1977. 40:1621–1628.

16. Gadducci A, Tana R, Fanucchi A, Genazzani AR. Biochemical prognostic factors and risk of relapses in patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007. 107:S23–S26.

17. van de Lande J, Davelaar EM, von Mensdorff-Pouilly S, Water TJ, Berkhof J, van Baal WM, et al. SCC-Ag, lymph node metastases and sentinel node procedure in early stage squamous cell cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2009. 112:119–125.

18. Gaarenstroom KN, Bonfrer JM, Kenter GG, Korse CM, Hart AA, Trimbos JB, et al. Clinical value of pretreatment serum Cyfra 21-1, tissue polypeptide antigen, and squamous cell carcinoma antigen levels in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer. 1995. 76:807–813.

19. Takeda M, Sakuragi N, Okamoto K, Todo Y, Minobe S, Nomura E, et al. Preoperative serum SCC, CA125, and CA19-9 levels and lymph node status in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002. 81:451–457.

20. Hong JH, Tsai CS, Lai CH, Chang TC, Wang CC, Chou HH, et al. Risk stratification of patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of cervix treated by radiotherapy alone. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005. 63:492–499.

21. Hong JH, Tsai CS, Chang JT, Wang CC, Lai CH, Lee SP, et al. The prognostic significance of pre- and posttreatment SCC levels in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix treated by radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998. 41:823–830.

22. Ferrandina G, Macchia G, Legge F, Deodato F, Forni F, Digesù C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma antigen in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma undergoing preoperative radiochemotherapy: association with pathological response to treatment and clinical outcome. Oncology. 2008. 74:42–49.

23. Yalman D, Aras AB, Ozkok S, Duransoy A, Celik OK, Ozsaran Z, et al. Prognostic factors in definitive radiotherapy of uterine cervical cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2003. 24:309–314.

24. Torre GC. SCC antigen in malignant and nonmalignant squamous lesions. Tumour Biol. 1998. 19:517–526.

25. Lomnytska MI, Becker S, Bodin I, Olsson A, Hellman K, Hellström AC, et al. Differential expression of ANXA6, HSP27, PRDX2, NCF2, and TPM4 during uterine cervix carcinogenesis: diagnostic and prognostic value. Br J Cancer. 2011. 104:110–119.

26. Min L, Dong-Xiang S, Xiao-Tong G, Ting G, Xiao-Dong C. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of Bmi-1 expression in human cervical cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011. 90:737–745.

27. Porika M, Tippani R, Mohammad A, Bollam SR, Panuganti SD, Abbagani S. Evaluation of serum human telomerase reverse transcriptase as a novel marker for cervical cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2011. 26:22–26.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download