Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the time when victims arrived at the hospital, the time of the attack, location, social relationship with assailants, detection of sperm, and whether a follow-up on sexual assault victims was possible.

Methods

Two hundred four sexual assault victims who visited the Gwangju One-stop Center and received gynecologic treatment from January 1st, 2008 to December 31st, 2008 were analyzed retrospectively.

Results

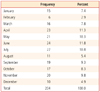

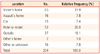

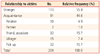

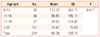

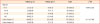

Most victims were raped in April and June. Most attacks happened between midnight and 3 AM. Victims visited the hospital between midnight and 9 AM. The most frequent locations of assault were the victim's house (65 cases, 31.9%). 55.4% of assailants were strangers to the victims. The mean interval time from rape to visit to the hospital by age was 172 hours (for victims≤13 years old) and 24 hours (≥20 years old). The detection rate of sperm in the vagina was 17.5% (154 victims) and the follow up rate was 11.3%. The injuries of the victims were as follows; 18 (8.9%) patients had genital injuries, 8 (3.9%) patients underwent psychological treatment, 1 (0.5%) patient had rib and mandible fracture with anal injury, and 2 (1%) patients became pregnant after the rape.

Conclusion

The doctors who treat sexual assault victims must consider the situation of the victims and the conditions for increasing the probability of sperm detection. We should also educate the patients so that they come back for follow-up checks for preventing physical and psychological complications.

Figures and Tables

References

1. DeLahunta EA, Baram DA. Sexual assault. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 40:648–660.

2. Adams JA, Knudson S. Genital findings in adolescent girls referred for suspected sexual abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996. 150:850–857.

3. Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center. 2008 Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center counseling statistics and counseling trend analysis. 2009. Seoul (KR): Korea Sexual Violence Relief Center.

4. Lee IS. Sexual assault. The 31st Korean Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Study lecture; 2001 May 18; Yongpyong (KR). 2002. Seoul: Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology;66–79.

5. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The 2001 compendium of selected publications. 2001. Washington (DC): The institute.

6. Hayman CR, Lanza C, Fuentes R, Algor K. Rape in the District of Columbia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972. 113:91–97.

7. Im MH. Rape in the district of young nahm: a review of 36 cases. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 1995. 38:1121–1218.

8. Yoon WS, Kweon I, Lee GS, Hur SY, Kim SJ, Choi BM. Clinical analysis of female sexual assault victims. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2003. 46:283–287.

9. Sharpe N. The significance of spermatozoa in victims of sexual offences. Can Med Assoc J. 1963. 89:513–514.

10. Warner CG. Rape and sexual assault: management & intervention. 1980. Germantown (MD): Aspen Systems Corp..

11. Kim JS, Park JY, Yoon YJ, Kim JH, Lee SA. Clinical significance of genital injury, detection of sperm, acid phosphatase activity, prostate specific acid phosphatase activity as proof of rape. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2008. 51:882–891.

12. Slaughter L, Brown CR, Crowley S, Peck R. Patterns of genital injury in female sexual assault victims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997. 176:609–616.

13. Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Frampton D. Follow-up of sexual assault victims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998. 179:336–342.

14. Song WY, Lee SR, Oh U. The Korean Psychological Association. Influence of communication style and sexual experience on perceived date rape risk. The annual symposium of the Korean Psychological Association collected papers. 2008. 2008 Aug 21-22; Seoul (KR). Seoul: The Korean Psychological Association;624–625.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download