Abstract

Detrusor underactivity (DU) or underactive bladder is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), but it is still poorly understood and underresearched. Although there has been a proposed definition by International Continence Society in 2002, no widely accepted diagnostic criteria have been established for this entity in clinical practice. Therefore, it has been rare to identify community-based researches on the epidemiology of DU until now. Only certain studies have reported the prevalence of DU in community-dwelling cohorts with significant LUTS using arbitrary urodynamic criteria for DU and these investigations have indicated that DU accounts for 25%–48% and 12%–24% of elderly men and women, respectively. However, these prevalence data based on the urodynamic definition apparently are limited in their extrapolation to the general population. Despite the clinical ambiguity of DU, its clinical effects on quality of life are quite significant, especially in the elderly population. An overall and proper comprehension of epidemiologic studies of DU may be crucial for better insight into DU, relevant decision making, and a more reasonable allocation of health resources. Therefore, researchers should find clues to the solution for the clinical diagnosis of this specific condition of LUTS from contemporary epidemiologic studies and try to develop a possible definition of ‘clinical’ DU from further studies.

Normal voiding is a complex but balanced mechanism, which is created by the correlation of detrusor contractile force generation to the urethral resistance against opening. When the bladder detrusor muscle is stimulated by parasympathetic outflow, the generation of a voiding force occurs and results in emptying of the bladder. Thus, if diminished detrusor contractility, increased resistance of the urinary outflow tract or a combination of these factors occur, incomplete emptying of the bladder that means unsuccessful voiding will be induced. According to the International Continence Society report in 2002, detrusor underactivity (DU) is defined as a contraction of reduced strength and/or duration, resulting in prolonged bladder emptying and/or failure to achieve complete bladder emptying within a normal time span [1]. However, the details of DU are still poorly understood and various other terms are often used to describe this entity of bladder dysfunction.

Compared with other causes of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), DU has received significantly less attention in clinical research because it has neither a standard, detailed definition nor widely accepted diagnostic criteria in clinical practice. In addition, the pathogenesis of DU is also underresearched and the absence of effective treatments has caused many urologists to consider DU an incurable, bothersome problem. Moreover, DU has been deemed as one of the age-related changes in the urinary bladder and its prevalence increases with age [2345]. Therefore, DU may be an important concern for urologic care in the near future as the proportion of the elderly population has been assessed at approximately 10% and is expected to approach 20% by 2050 [678].

In this review, we summarized the epidemiologic data of DU from contemporary reports and aimed to investigate current problems in the estimation of the DU prevalence in the clinical setting and further directions regarding the relevant researches to expand the clinician's understanding of this poorly understood condition.

DU frequently accompanies a complex set of symptoms including poor intermittent streams, residual urine sense after voiding, and hesitancy. The main etiology of DU is associated with dysfunction of detrusor contractility and the current diagnosis of DU requires a pressure-flow study (PFS) that might be quite bothersome for clinicians. Other terms used to describe DU include underactive bladder (UAB), impaired detrusor contractility, and relatively older terms such as hypotonic bladder or detrusor areflexia [9]. Among these synonymous terms, UAB and impaired contractility are the two of the most commonly used terms that explain this condition caused by only decreased activity or contractile ability of the detrusor. While the term DU suggests a decreased functional status of the detrusor muscle, UAB is more likely to describe the symptoms of the patients. However, these terms might misguide the real concept of DU because DU might develop not only from decreased detrusor contractility but also from altered innervation of detrusor muscle. Moreover, decreased detrusor contractile velocity also plays a potentially important role and should be included in the definition of DU [10].

The most commonly observed symptoms among patients with DU are hesitancy, sensation of incomplete emptying caused by an increased postvoid residual (PVR), straining to void, urgency, frequency, nocturia, and incontinence. Recurrent infections of the urinary tract are also seen in a significant number of patients because persistent building up of urine can result overflow incontinence and the back flow of urine into upper urinary tract, including the ureter and kidney [11]. Some studies have reported that the complex symptoms of DU overlap significantly with the symptoms of overactive bladder (OAB) [4]. This implies that DU should not be diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms but by referring to the urodynamic findings. In addition, empirically treating the symptoms of DU before acquiring a urodynamic assessment might not be recommended in certain previous studies [1112].

As for the diagnosis of DU, it starts with reviewing medical history and verifying neurologic comorbidity of the patients. A frequency-volume chart might be helpful for visualizing the voiding pattern. Some studies even recommend that patients undergo a thorough physical examination, including checking the perianal sense and sphincter tone as well as the bulbocavernous reflex [11].

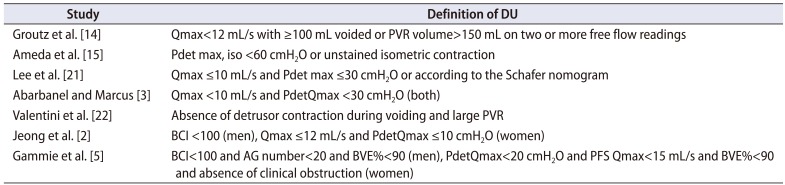

However, the only definitive method for diagnosing DU is invasive PFS at present. The urodynamic criteria for DU markedly vary, but 2 values, the maximum flow rate (Qmax) and the detrusor pressure at maximum flow (PdetQmax), are considered important in the diagnosis because these values enable the approximation of detrusor contractile strength. A 10-year follow-up long-term study from Thomas et al. [13] used Qmax<15 mL/s and PdetQmax<40 cmH2O as their diagnostic criteria of DU and they initially treated DU patients with watchful waiting. Among the 69 male patients who initially underwent for watchful waiting, no significant diminishment of urodynamic parameters was observed during the follow-up period. Especially, the mean PVR measured at the end of the research was 107–125 mL and DU often did not result in chronic urinary retention, which might be generally defined as a PVR>300 mL. Therefore, they concluded that DU may not be progressive in most nonneurogenic male patients [13]. However, other studies applied different urodynamic criteria, which might have caused the different outcomes including the prevalence. Our previous study reported in 2012 incorporated Qmax≤12 mL/s and PdetQmax≤10 cmH2O for females and a bladder contractility index (BCI)<100 for males [2], but each study has an individual urodynamic criteria in their epidemiologic studies of the prevalence of DU (Table 1).

Although the prevalence of DU increases in older patients as it is generally age-related, no epidemiological study has analyzed the prevalence of DU related symptoms such as LUTS and impaired storage function. This is probably due to the essential obstacle that DU can only be diagnosed by a PFS, making the analysis and interpretation of epidemiologic information such as the prevalence and natural pathway of the disease entity difficult.

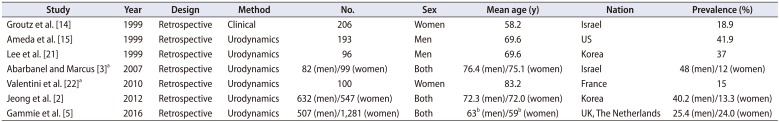

In this review, prevalence of DU is examined within the patients without definite pathophysiologies for DU because more attention might be paid to the prevalence among the community-dwelling ordinary population suffering from LUTS than to that in the population with ‘definite’ causes affecting the detrusor function in clinical practice. Table 2 summarizes the studies on the prevalence of DU among nonneurogenic patients who suffered from LUTS and underwent urodynamic studies. In our previous investigation that was the first epidemiological research performed among a large Korean population to our knowledge [2], 1,179 patients older than 65 years were analyzed and the prevalence of DU was 40.2% and 13.3% in men and women with LUTS, respectively, where the prevalence increased with age in both gender. Moreover, the symptoms of OAB or bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) coexisted in 46.5% of male patients while 72.6% of female patients showed the symptoms of OAB or stress urinary incontinence with DU. Thus, we presented that DU can be the result of other voiding function pathophysiologies or might be an independent disease entity caused by the aging process.

Abarbanel and Marcus [3] studied 181 community-dwelling LUTS patients aged ≥70 years and observed detrusor contractile dysfunction in 48% of men and 12% of women. In addition, involuntary bladder contraction was also accompanied in 2/3 of men and 1/2 of women with detrusor contractile dysfunction, and 10% of the corresponding patients with involuntary bladder contraction had BOO. They also presented that almost 10%–20% of men confirmed to have a decreased flow rate by a PFS exhibited DU.

According to the recent review from Osman et al. [4], 9%–28% of men with the age <50 years showed DU, but the prevalence increased to 48% in older men aged >70 years. They also presented that older women aged >70 years had a prevalence of DU ranging from 12% to 45%. In particular, the prevalence of DU patients was dominant among the institutionalized patients. Moreover, Thomas et al. [13] also reported in their long-term study (mean follow-up period of 13.6 years) that 2/3 of institutionalized elderly patients with incontinence had symptoms of UAB. These previously mentioned retrospective studies have methodological limitations because the diagnostic criteria contain significant variations. Thus, the clinical results are inapplicable to the general population, but they still emphasized that DU is significantly dominant among the institutionalized patients or those in secondary care.

Unlike other researchers, Groutz et al. [14] used only free Qmax and PVR in the diagnostic criteria, instead of the PFS parameters, and reported an 18.9% of DU among 206 women with LUTS. Ameda et al. [15] defined the presence of DU as the maximum isometric detrusor pressure<60 cmH2O or unsustained isometric contraction and identified that 41.9% of their male cohort had DU.

Recently, Gammie et al. [5] identified that 25.4% and 24.0% of men and women who had received a PFS due to LUTS showed the presence of DU when the diagnostic criteria were applied as follows; BCI<100, Abrams-Griffith number<20 and bladder voiding efficiency (BVE) % <90 for men and PdetQmax<20 cmH2O, PFS Qmax<15 mL/s, BVE %<90 and the absence of clinical obstruction for women.

In male patients with DU, it seems that a significant number of patients might receive transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P) for the treatment of DU. In the recent study of Hoag and Gani [16], DU was defined as a BCI<100 and the absence of definite BOO in a PFS. Among the 343 patients analyzed, prevalence of DU was 23% (79 patients), and 25 of 79 patients with DU were male. Of these male patients with DU, 28.0% had previously received TUR-P for the treatment of LUTS. Jeong et al. [17] compared the effect of TUR-P between 25 patients with unobstructed and underactive detrusor function and 46 patients with obstructed and/or normal detrusor contractility. Patients with DU had less improvement in their symptom score and operative satisfaction than those with obstructed and/or normal detrusor contractility after surgery. However, the authors insisted that the TUR-P is thought to be an optional surgical procedure for treating the men with DU who do not respond to conservative medical treatment as there was also significant improvement in symptom score and PVR after surgery in DU group and 64% of these patients were satisfied. Nevertheless, further large study with long-term follow-up needs to be done to verify the effect of TUR-P in male patients with DU.

The age-related feature of DU has been widely accepted in many studies [2345678], yet some studies have failed to prove its age relation due to vague diagnostic criteria. Recently, Valente et al. [18] studied the prevalence of UAB in 633 subjects and the results showed no definite association between UAB symptoms and age. However, they observed an age-related dominance of BOO within the population and insisted that distinguishing the symptoms of BOO from those of pure DU is extremely tricky and that the diagnosis of DU based upon clinical symptoms is complex. Ameda et al. [15] also showed no significant association between age and impaired detrusor contractility in their study of 193 men with LUTS.

Certain disease conditions, such as infection, inflammation, or peripheral neuropathy, have been shown to be associated with DU by causing neurologic alterations. According to the study of Khan et al. [19], urodynamic assessment in a series of 18 AIDS patients with LUTS revealed that 61.1% (11 of 18 patients) had neurogenic bladder and 36% of patients with neurogenic bladder had DU. Bansal et al. [20] studied 52 men with diabetes who had presented with bothersome LUTS (mean age 61 years) and showed that 79% of the patients had DU while 21% had delayed first voiding sense and 25% had increased bladder capacity.

Although most of published epidemiologic data were from the community-dwelling cohorts with significant LUTS through the arbitrary urodynamic criteria for DU, the reported prevalence is 25%–48% and 12%–24% in elderly men and women, respectively. Therefore, DU is considered as common condition among various LUTS and physicians who treat the elderly with LUTS should understand the age-related pathophysiological changes of the lower urinary tract and recognize that this population most likely has DU.

The prevalence data of DU examined in this review are based on the urodynamic definition and are limited in their extrapolation to the general population. However, an overall and proper comprehension of epidemiologic studies of DU may be crucial for better insight into DU, relevant decision making, and more reasonable allocation of health resources. Therefore, researchers should find clues to the solution for the clinical diagnosis of this specific condition of LUTS from contemporary epidemiologic studies and try to develop possible definition and diagnostic algorithm of ‘clinical’ DU from further studies.

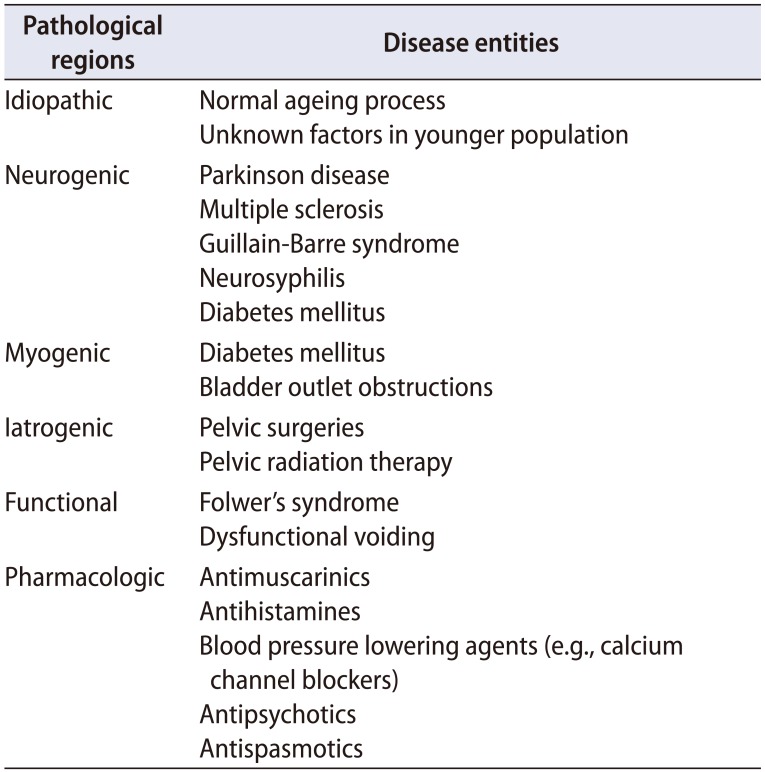

Many previous clinical studies suggested that the pathogenesis of DU is multifactorial [4]. The potential risk factors associated with the pathogenesis of DU include normal ageing, diabetes mellitus, BOO, pelvic surgery, and neurologic disabilities involving the lumbosacral nerve plexus (Table 3). In addition, a profound estrogen deficiency might be a risk factor of DU by causing the biochemical variations related to detrusor contractility or its innervation and aged people taking multiple drugs such as calcium channel blockers, alpha receptor agonists and neuroleptics also may show DU (Table 3) [2122232425]. Some risk factors are mentioned in this review and other pathophysiologies are described elsewhere in this issue.

Insufficient postganglionic efferent nerve stimulation is generated in some neuro-pathological cases such as cerebrovascular accident (CVA) and it may lead to DU by influencing perception and outflow of urine [26]. Urine retention frequently occurs in the acute stage after CVA, and most of the patients need urethral catheterization for a significant period. Many studies have noted the relation between the location of CVA lesion and dysfunction in bladder storage or voiding. Yum et al. [27] showed that patients with pontine infarcts had predominantly decreased bladder capacity (62% of the patients) compared to those with medullary infarcts (11%). However, other studies still present the location of CVA has no correlation with the pattern of voiding dysfunction [28].

Most patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) experience DU or detrusor areflexia during the spinal shock period. After spinal shock, various types of bladder dysfunction can occur, which are dependent on the level of the injury. In the sacral SCI, damages in both sacral parasympathetic nucleus and Onuf's nucleus can be done, which consecutively results in detrusor areflexia with impaired or normal bladder compliance [29].

Diabetic cystopathy is one of the common causes of DU. Diabetes influences bladder function in both myogenic and neurogenic mechanism. The main characteristic of diabetic cystopathy is predominantly decreased ability of bladder emptying [30]. In patients with diabetes, hyperglycemia induced autonomic neuropathy causes bladder dysfunction [31]. The pathophysiology of myogenic mechanisms is not well understood, but it has been postulated that variations of detrusor myogenic intracellular signaling might play crucial roles as etiology [32]. In addition, Bansal et al. [20] suggested that diabetic cystopathy is significantly associated with DU in conjunction with high PVR, but not DU alone

Any pathological disruption that varies the normal structure or function of the detrusor myocytes (or even its extracellular environment) can result in detrusor contraction failure [33]. This implies that impaired detrusor contraction can occur even when the efferent parasympathetic nerve system is fully functional [34]. According to the study of Elbadawi et al. [35], ultrastructural changes of detrusor myocytes can be detected in electron microscopy and these microscopic variations might result in derangements of the factors related to contractility including calcium storage or other ion exchanges [34].

The imprecise and interchanging use of terminology has contributed immense confusion in the diagnosis and therapy of DU. Therefore, a standard terminology encompassing the relationship between the symptoms (UAB) and the urodynamic findings (DU) should be defined. Further research should also include the prevalence of DU in asymptomatic populations and detrusor contractility and detrusor activity must be distinguished in the future studies. Moreover, the etiologic causes of DU and the specific clinical symptoms resulting from DU should be evaluated because they are deeply related to the therapeutic goal for the disease.

DU is still a poorly understood and treated bladder dysfunction that yields various morbidities. Multiple terms, various definition criteria and many epidemiological facts regarding DU have been introduced in this review. The reported prevalence of DU is 25%–48% and 12%–24% in elderly men and women with LUTS, respectively, based on the arbitrary urodynamic criteria for DU. We hope this review will promote additional research on this condition and provide further improvements of the clinical criteria for DU.

References

1. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002; 21:167–178. PMID: 11857671.

2. Jeong SJ, Kim HJ, Lee YJ, Lee JK, Lee BK, Choo YM, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of detrusor underactivity among elderly with lower urinary tract symptoms: a comparison between men and women. Korean J Urol. 2012; 53:342–348. PMID: 22670194.

3. Abarbanel J, Marcus EL. Impaired detrusor contractility in community-dwelling elderly presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms. Urology. 2007; 69:436–440. PMID: 17382138.

4. Osman NI, Chapple CR, Abrams P, Dmochowski R, Haab F, Nitti V, et al. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: a new clinical entity? A review of current terminology, definitions, epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol. 2014; 65:389–398. PMID: 24184024.

5. Gammie A, Kaper M, Dorrepaal C, Kos T, Abrams P. Signs and symptoms of detrusor underactivity: an analysis of clinical presentation and urodynamic tests from a large group of patients undergoing pressure flow studies. Eur Urol. 2016; 69:361–369. PMID: 26318706.

6. United Nations Population Division. World population ageing 1950–2050. New York: United Nations Publications;2001.

7. van Koeveringe GA, Rademakers KL, Birder LA, Korstanje C, Daneshgari F, Ruggieri MR, et al. Detrusor underactivity: pathophysiological considerations, models and proposals for future research. ICI-RS 2013. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014; 33:591–596. PMID: 24839258.

8. Smith PP, Birder LA, Abrams P, Wein AJ, Chapple CR. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: symptoms, function, cause-what do we mean? ICI-RS think tank 2014. Neurourol Urodyn. 2016; 35:312–317. PMID: 26872574.

9. Madjar S, Appell RA. Impaired detrusor contractility: anything new? Curr Urol Rep. 2002; 3:373–377. PMID: 12354345.

10. Cucchi A, Quaglini S, Guarnaschelli C, Rovereto B. Urodynamic findings suggesting two-stage development of idiopathic detrusor underactivity in adult men. Urology. 2007; 70:75–79. PMID: 17656212.

11. Miyazato M, Yoshimura N, Chancellor MB. The other bladder syndrome: underactive bladder. Rev Urol. 2013; 15:11–22. PMID: 23671401.

12. Chapple CR, Osman NI, Birder L, van Koeveringe GA, Oelke M, Nitti VW, et al. The underactive bladder: a new clinical concept? Eur Urol. 2015; 68:351–353. PMID: 25770481.

13. Thomas AW, Cannon A, Bartlett E, Ellis-Jones J, Abrams P. The natural history of lower urinary tract dysfunction in men: minimum 10-year urodynamic follow-up of untreated detrusor underactivity. BJU Int. 2005; 96:1295–1300. PMID: 16287448.

14. Groutz A, Gordon D, Lessing JB, Wolman I, Jaffa A, David MP. Prevalence and characteristics of voiding difficulties in women: are subjective symptoms substantiated by objective urodynamic data? Urology. 1999; 54:268–272. PMID: 10443723.

15. Ameda K, Sullivan MP, Bae RJ, Yalla SV. Urodynamic characterization of nonobstructive voiding dysfunction in symptomatic elderly men. J Urol. 1999; 162:142–146. PMID: 10379758.

16. Hoag N, Gani J. Underactive bladder: clinical features, urodynamic parameters, and treatment. Int Neurourol J. 2015; 19:185–189. PMID: 26620901.

17. Jeong YS, Lee SW, Lee KS. The effect of transurethral resection of the prostate in detrusor underactivity. Korean J Urol. 2006; 47:740–746.

18. Valente S, DuBeau C, Chancellor D, Okonski J, Vereecke A, Doo F, et al. Epidemiology and demographics of the underactive bladder: a cross-sectional survey. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014; 46(Suppl 1):S7–S10. PMID: 25238889.

19. Khan Z, Singh VK, Yang WC. Neurogenic bladder in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Urology. 1992; 40:289–291. PMID: 1523760.

20. Bansal R, Agarwal MM, Modi M, Mandal AK, Singh SK. Urodynamic profile of diabetic patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: association of diabetic cystopathy with autonomic and peripheral neuropathy. Urology. 2011; 77:699–705. PMID: 21195463.

21. Lee JG, Shim KS, Koh SK. Incidence of detrusor underactivity in men with prostatism older than 50 years. Korean J Urol. 1999; 40:347–352.

22. Valentini FA, Robain G, Marti BG, Nelson PP. Urodynamics in a community-dwelling population of females 80 years or older. Which motive? Which diagnosis? Int Braz J Urol. 2010; 36:218–224. PMID: 20450508.

23. Chancellor MB, Kaufman J. Case for pharmacotherapy development for underactive bladder. Urology. 2008; 72:966–967. PMID: 18774593.

24. Sánchez-Ortiz RF, Wang Z, Menon C, DiSanto ME, Wein AJ, Chacko S. Estrogen modulates the expression of myosin heavy chain in detrusor smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001; 280:C433–C440. PMID: 11171561.

25. Chuang YC, Plata M, Lamb LE, Chancellor MB. Underactive bladder in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015; 31:523–533. PMID: 26476113.

26. Suskind AM, Smith PP. A new look at detrusor underactivity: impaired contractility versus afferent dysfunction. Curr Urol Rep. 2009; 10:347–351. PMID: 19709481.

27. Yum KS, Na SJ, Lee KY, Kim J, Oh SH, Kim YD, et al. Pattern of voiding dysfunction after acute brainstem infarction. Eur Neurol. 2013; 70:291–296. PMID: 24052006.

28. Araki I, Matsui M, Ozawa K, Takeda M, Kuno S. Relationship of bladder dysfunction to lesion site in multiple sclerosis. J Urol. 2003; 169:1384–1387. PMID: 12629367.

29. Cruz CD, Coelho A, Antunes-Lopes T, Cruz F. Biomarkers of spinal cord injury and ensuing bladder dysfunction. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015; 82-83:153–159. PMID: 25446137.

30. Lifford KL, Curhan GC, Hu FB, Barbieri RL, Grodstein F. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of developing urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005; 53:1851–1857. PMID: 16274364.

31. Hill SR, Fayyad AM, Jones GR. Diabetes mellitus and female lower urinary tract symptoms: a review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008; 27:362–367. PMID: 18041770.

32. Daneshgari F, Liu G, Birder L, Hanna-Mitchell AT, Chacko S. Diabetic bladder dysfunction: current translational knowledge. J Urol. 2009; 182(6 Suppl):S18–S26. PMID: 19846137.

33. Natsume O. Detrusor contractility and overactive bladder in patients with cerebrovascular accident. Int J Urol. 2008; 15:505–510. PMID: 18422572.

34. Brierly RD, Hindley RG, McLarty E, Harding DM, Thomas PJ. A prospective controlled quantitative study of ultrastructural changes in the underactive detrusor. J Urol. 2003; 169:1374–1378. PMID: 12629365.

35. Elbadawi A, Yalla SV, Resnick NM. Structural basis of geriatric voiding dysfunction. II. Aging detrusor: normal versus impaired contractility. J Urol. 1993; 150(5 Pt 2):1657–1667. PMID: 8411454.

Table 1

Urodynamic definitions of detrusor underactivity in a series of nonneurogenic patients who suffered from lower urinary tract symptoms

| Study | Definition of DU |

|---|---|

| Groutz et al. [14] | Qmax<12 mL/s with ≥100 mL voided or PVR volume>150 mL on two or more free flow readings |

| Ameda et al. [15] | Pdet max, iso <60 cmH2O or unstained isometric contraction |

| Lee et al. [21] | Qmax ≤10 mL/s and Pdet max ≤30 cmH2O or according to the Schafer nomogram |

| Abarbanel and Marcus [3] | Qmax <10 mL/s and PdetQmax <30 cmH2O (both) |

| Valentini et al. [22] | Absence of detrusor contraction during voiding and large PVR |

| Jeong et al. [2] | BCI <100 (men), Qmax ≤12 mL/s and PdetQmax ≤10 cmH2O (women) |

| Gammie et al. [5] | BCI<100 and AG number<20 and BVE%<90 (men), PdetQmax<20 cmH2O and PFS Qmax<15 mL/s and BVE%<90 and absence of clinical obstruction (women) |

DU, detrusor underactivity; Qmax, maximum flow rate; PVR, postvoid residual; Pdet max, iso, maximum isometric detrusor pressure; Pdet max, maximum detrusor pressure; PdetQmax, detrusor pressure at maximum flow rate; BCI, bladder contractility index; AG number, Abrams-Griffith number; BVE, bladder voiding efficiency; PFS, pressure-flow study.

Table 2

Prevalence of detrusor underactivity in a series of nonneurogenic patients who suffered from lower urinary tract symptoms and underwent urodynamic studies

| Study | Year | Design | Method | No. | Sex | Mean age (y) | Nation | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groutz et al. [14] | 1999 | Retrospective | Clinical | 206 | Women | 58.2 | Israel | 18.9 |

| Ameda et al. [15] | 1999 | Retrospective | Urodynamics | 193 | Men | 69.6 | US | 41.9 |

| Lee et al. [21] | 1999 | Retrospective | Urodynamics | 96 | Men | 69.6 | Korea | 37 |

| Abarbanel and Marcus [3]a | 2007 | Retrospective | Urodynamics | 82 (men)/99 (women) | Both | 76.4 (men)/75.1 (women) | Israel | 48 (men)/12 (women) |

| Valentini et al. [22]a | 2010 | Retrospective | Urodynamics | 100 | Women | 83.2 | France | 15 |

| Jeong et al. [2] | 2012 | Retrospective | Urodynamics | 632 (men)/547 (women) | Both | 72.3 (men)/72.0 (women) | Korea | 40.2 (men)/13.3 (women) |

| Gammie et al. [5] | 2016 | Retrospective | Urodynamics | 507 (men)/1,281 (women) | Both | 63b (men)/59b (women) | UK, The Netherlands | 25.4 (men)/24.0 (women) |

Table 3

Possible risk factors of detrusor underactivity

PDF

PDF Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download