Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to assess the patient-reported outcome (PRO) and efficacy of add-on low-dose antimuscarinic therapy in over-active bladder (OAB) patients with suboptimal response to 4-week treatment with beta 3 agonist monotherapy (mirabegron, 50 mg).

Materials and Methods

We enrolled OAB patients with 4-week mirabegron (50 mg) treatment if the patients' symptoms improved, but not to a satisfactory extent (patient perception of bladder condition [PPBC] ≥4). Enrolled patients had 8-week low-dose antimuscarinics add-on therapy (propiverine HCl, 10 mg). Patients recorded 3-day voiding diary at screening, enrollment (after 4 weeks of mirabegron monotherapy) and after 8 weeks of add-on therapy. We assessed the change of PRO (PPBC) as a primary end point and the efficacy of add-on therapy (change of frequency, urgency, urinary urgency incontinence [UUI] based on voiding diary) as a secondary end point.

Results

Thirty patients (mean age, 62.3±12.8 years; mean symptom duration, 16.0±12.3 months) were finally enrolled in the study. The mean PPBC value was 4.3±0.4 after mirabegron monotherapy, and decreased to 3.2±1.0 after 8-week add-on therapy. The mean urinary frequency decreased from 10.1±3.1 to 8.8±3, the mean number of urgency episodes decreased from 3.6±1.6 to 1.8±1.2 and the number of urgency incontinence episodes decreased from 0.7±1.0 to 0.2±0.5 after add-on therapy. No patients had event of acute urinary retention and three patients complained of mild dry mouth after add-on therapy.

Overactive bladder (OAB) is characterized by symptoms of urinary urgency, usually accompanied by daytime frequency and nocturia, with or without urinary urgency incontinence (UUI), in the absence of urinary tract infection or other pathological conditions [1]. Among the OAB symptoms, UUI—noted in approximately one-third of OAB cases—leads to the most discomfort [2]. Compared with continent (dry) patients with OAB, those who are incontinent (wet) experience a markedly reduced quality of life (QoL), and report higher rates of depression and emotional stress [3], thus indicating that incontinent patients with OAB who are refractory to treatment are likely to be extremely dissatisfied with their QoL.

Antimuscarinic treatment and the beta 3 adrenoreceptor agonist mirabegron are the oral pharmacotherapies used to treat OAB. Both classes of drugs show similar efficacy; however, unlike antimuscarinics, mirabegron is not associated with anticholinergic side effects [4]. Hence, many patients have been started on mirabegron therapy for OAB in recent years. Due to the similar efficacy between mirabegron and antimuscarinics, some patients receiving mirabegron treatment may exhibit an insufficient response. Antimuscarinic therapy can be added to mirabegron monotherapy in these patients. In fact, a randomised double-blind multicentre phase 3B (BESIDE) study recently showed that the addition of mirabegron (50 mg) to a solifenacin (5 mg) regimen further improved the OAB symptoms as compared to added treatment with 5- or 10-mg solifenacin in patients who remained incontinent after initial therapy with solifenacin (5 mg) [5]. Nevertheless, no study to date has assessed the addition of low-dose antimuscarinics to a regimen containing mirabegron (50 mg) in patients with an unsatisfactory response to the monotherapy. This may be a useful alternative as mirabegron is currently selected as the initial treatment for OAB [6], and add-on therapy with low-dose antimuscarinics may help avoid the side-effects of standard-dose antimuscarinics, such as acute urinary retention and high discontinuation rates in patients with suboptimal response to mirabegron monotherapy [7]. In the present study, we primarily aimed to assess the change in the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC) [8] as a patient-reported outcome (PRO) of add-on therapy in patients who exhibited suboptimal response to monotherapy. Moreover, we sought to evaluate the efficacy of such add-on therapy. The secondary aim was to assess the safety of add-on therapy.

Considering the ethical aspects of data collection, the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (approval number: S2016-1815-0001). OAB patients who visited the outpatient clinic of our institution from May 2015 to September 2015 were screened. Among these, patients who showed a suboptimal response to initial mirabegron monotherapy were selected for the current study.

The inclusion criteria were an age >18 years with OAB symptom duration of >3 months. Patients with stress urinary incontinence, mixed urinary incontinence, urinary tract infection, urinary stone, or interstitial cystitis were excluded. The interstitial cystitis patients diagnosed according to International Continence Society guidelines. In order to make exact differential diagnosis between OAB and interstitial cystitis, we asked bladder pain/discomfort with bladder filling to the patients. Patients who had voiding symptoms which were related with bladder outlet obstruction and who took medications, such as alpha-blocker, 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor, antihistamine, antidepressant and antimuscarinic agents were excluded. The male patients who showed prostate-specific antigen ≥10 ng/mL and patients who had any neurogenic problems (stroke, spinal cord injury, etc.) were also excluded.

A suboptimal response to treatment was considered in cases where the symptoms improved, but not to a satisfactory extent (PPBC≥4). In these patients, add-on therapy with a low-dose antimuscarinic agent (propiverine HCl, 10 mg) was administered. After 8 weeks of add-on therapy, the PPBC was assessed again to confirm the improvement due to the add-on therapy. A 3-day voiding diary was recorded at screening, enrollment (after monotherapy), and after add-on therapy (Fig. 1).

The patients recorded the PPBC, as a PRO, at 4 weeks after the initiation of mirabegron monotherapy and 8 weeks after the initiation of add-on therapy. The change in the PPBC value was the primary study endpoint, whereas the efficacy of the add-on therapy was the secondary end-point, in terms of the mean change in urinary frequency, number of urgency episodes, and number of urgency incontinence episodes per day before and after add-on therapy. The safety assessments included the postvoid residual volume, which was evaluated using a bladder scan.

We used the Student t-test for comparative analysis. Before using the t-test, we assessed for equal variance with the F-test. We conducted t-tests based on an assumption of heteroscedasticity for each result. The statistical assessments were considered significant when p-values were <0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 18.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

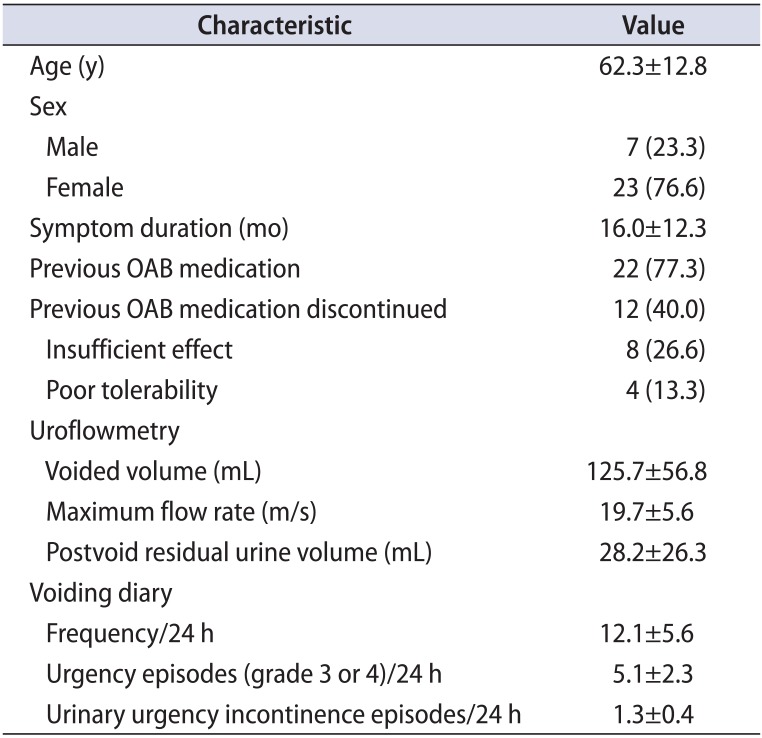

A total of 30 patients who answered PPBC points greater than 4 after mirabegron monotherapy were enrolled, and their medical records were reviewed. The patient demographics and baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean age (±standard deviation [SD]) was 62.3±12.8 years, and the mean symptom duration was 16.0±12.3 months. Seven patients (23.3%) were male and 23 (76.6%) were female. A total of 22 patients (77.3%) had ever taken antimuscarinic agents, whereas 12 patients discontinued antimuscarinic therapy due to an insufficient effect (n=8) or poor tolerability (n=4). The mean (±SD) urinary frequency, number of urgency incontinence episodes, and number of urgency episodes (grade 3 or 4) were 12.1±5.6, 5.1±2.3, and 1.3±0.4, respectively. The mean voided volume, maximum flow rate, and postvoid residual urine were 125.7±56.8 mL, 19.7±5.6 m/s, and 28.2±26.3 mL on uroflowmetry analysis prior to mirabegron monotherapy (Table 1).

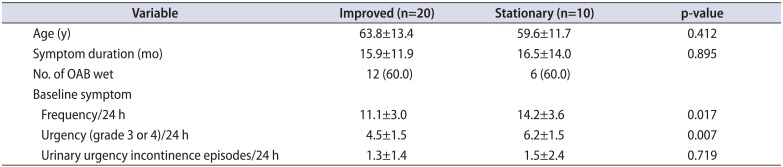

Among the 30 study patients (n=30), 10 (33.3%), and 20 (66.6%) exhibited a value of 4 or 5 for the PPBC, respectively, after 4 weeks of mirabegron monotherapy. However, 3 (10.0%) and 11 patients (36.6%) exhibited a value of 4 and 5 for the PPBC, respectively, after 8 weeks of add-on therapy with low-dose antimuscarinics. Ten patients (33.3%), 4 patients (13.3%), and 2 patients (6.6%) exhibited values of 3, 2, and 1 for the PPBC at 8 weeks after add-on therapy with low-dose antimuscarinics, respectively (Fig. 1). Patients with stationary PPBC value had severe baseline symptom with significantly more episodes of frequency and urgency (Table 2).

The mean frequency decreased from 10.1±3.1 to 8.8±3.0 after 8 weeks of add-on therapy. The mean number of urgency episodes also decreased from 3.6±1.6 to 1.8±1.2 after add-on therapy. The number of UUI episodes at baseline decreased from 0.7±1.0 to 0.2±0.5 after add-on therapy. There was no event of acute urinary retention. Patients mean residual urine volume changed from 28.2±26.3 to 31.2±29.1 (p=0.156). Three patients complained of mild dry mouth after add-on therapy; however, this did not lead to the discontinuation of add-on therapy in such cases (Figs. 2, 3).

In the present study, we clearly demonstrate the suitable efficacy and safety of add-on therapy with a low-dose antimuscarinic agent to mirabegron monotherapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the efficacy of low-dose antimuscarinic treatment as add-on therapy to mirabegron monotherapy due to a suboptimal response. These findings are valuable, as the addition of low-dose antimuscarinic agents to mirabegron therapy in OAB patients with a suboptimal response to mirabegron monotherapy could serve as a well-optimized secondary plan to avoid the side-effects or discontinuation of standard-dose of antimuscarinic treatment and to increase its insufficient efficacy on OAB symptoms [9].

As the efficacy of mirabegron and standard antimuscarinic agents is similar, the improvements in symptoms may often be insufficient, thus leading to dissatisfaction with the QoL after mirabegron monotherapy [10]. Furthermore, we are aware that the discontinuation rates of standard-dose antimuscarinic treatment can be as high as 50% during the first 3 months due to a combination of ineffectiveness and side-effects [9]. Moreover, the use of chronic antimuscarinic agents in cognitively normal adults was recently associated with cognitive impairment and brain atrophy [11]. Thus, combination therapy with mirabegron and low-dose antimuscarinic agents is the best option for OAB patients with a suboptimal response to mirabegron monotherapy. To evaluate the efficacy of add-on therapy, we used PPBC as a PRO, which represents a subjective scale, as well as the results of a voiding diary, which represents an objective scale, including urinary frequency, number of urgency episodes, and number of urgency incontinence episodes.

OAB is a common debilitating condition that affects the physical, social, and psychological health of millions of patients worldwide [12]. The current treatments are based on bladder and fluid re-education, with the addition of antimuscarinic drug therapy in those resistant to conservative measures. Although antimuscarinic therapy remains a mainstay of pharmaceutical treatment, the long-term persistence rates are poor, with rates as low as 12% at 1 year [13]. Mirabegron is a beta 3 agonist used for the treatment of OAB. Current trials suggest that the efficacy of mirabegron is similar to that of antimuscarinics, although the side-effects are less frequent [414]. Mirabegron is a relatively new drug and shows decreased side-effects; hence, it is now used as the initial medication for OAB. However, some OAB patients may exhibit inadequate response to the medication due to its similar efficacy with antimuscarinic drugs. To get clear results, we excluded interstitial cystitis patients who might show poor response for antimuscarinic drugs based on patients' symptom. In such cases, add-on antimuscarinic treatment can be considered. However, to our knowledge, no data are available regarding the efficacy of add-on low-dose antimuscarinic therapy in patients with suboptimal response to mirabegron monotherapy. The primary objective was to assess the improvement in the PRO after add-on therapy in unsatisfied OAB patients treated with mirabegron, whereas the secondary objective was to assess the efficacy and safety of add-on therapy.

The superiority of combination therapy with beta 3 agonist and antimuscarinic treatment was demonstrated in the previous BESIDE trial [5]. BESIDE was a randomized double-blind parallel-group study of 2,401 patients with daily UUI episodes. In that study, combination therapy was superior to solifenacin (5 mg) in reducing the number of UUI episodes per day from baseline. Furthermore, combination therapy was not inferior to solifenacin (10 mg) in UUI improvement. Interestingly, a higher proportion of patients were dry after combination therapy (46%) than after solifenacin (10 mg; 40.2%). In that trial, mirabegron was used as an add-on therapy to initial antimuscarinic treatment, in contrast to the present study. Importantly, the efficacy of add-on therapy was good in patients with insufficient response to mirabegron. Combination therapy may be suitable in such cases due to the independent mode of action. Under physiological conditions, noradrenaline acts mainly on β3-adrenoceptors in the detrusor, whereas neuronally released acetylcholine acts mainly on the M3 receptors of the bladder [15]. We hypothesized that the reverse order would also be effective for OAB symptoms, even though a low dose of antimuscarinic agents was used in our present study. To our knowledge, our current report is the first study to assess this reverse order of medication and evaluate the efficacy of add-on therapy with a low-dose antimuscarinic agent.

The QoL involves sociodemographic, clinical, psychological, and social factors, which emphasize the importance of assessing patient perceptions of treatment efficacy on OAB symptoms. Hence, the concept of PRO was recently described in much detail. Such a subjective assessment could support the results of objective examinations. The validity of bladder health questionnaires, including PPBC, has been confirmed in previous studies, and the parameters demonstrate a strong correlation with symptom improvement based on bladder diary assessment [16]. In the present study, we used PPBC to demonstrate the efficacy of add-on therapy. We found that the PPBC significantly decreased, and other voiding parameters, including urinary frequency, number of urgency episodes, and number of urgency incontinence episodes, improved after add-on therapy. With regard to safety, the add-on therapy could be well tolerated. However, the notable limitations of the present study include its retrospective nature and its small cohort.

Add-on therapy with a low-dose antimuscarinic agent to mirabegron monotherapy shows good efficacy and safety in patients with suboptimal response (score 4–5 in PPBC) to to 4-week mirabegron monotherapy. This treatment efficacy was demonstrated in particular via clinically meaningful improvements in the PPBC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant numbers: HI14C2321 and HI14C3365), and by the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF (No. 2015R1A2A1A15054754).

References

1. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002; 21:167–178. PMID: 11857671.

2. Tubaro A. Defining overactive bladder: epidemiology and burden of disease. Urology. 2004; 64(6 Suppl 1):2–6.

3. Martínez Agulló E, Ruíz Cerdá JL, Gómez Pérez L, Rebollo P, Pérez M, Chaves J. Impact of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder syndrome on health-related quality of life of working middle-aged patients and institutionalized elderly patients. Actas Urol Esp. 2010; 34:242–250. PMID: 20416241.

4. Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, Desroziers K, Neine ME, Siddiqui E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol. 2014; 65:755–765. PMID: 24275310.

5. Drake MJ, Chapple C, Esen AA, Athanasiou S, Cambronero J, Mitcheson D, et al. Efficacy and safety of mirabegron add-on therapy to solifenacin in incontinent overactive bladder patients with an inadequate response to initial 4-week solifenacin monotherapy: a randomised double-blind multicentre phase 3B study (BESIDE). Eur Urol. 2016; 70:136–145. PMID: 26965560.

6. Warren K, Burden H, Abrams P. Mirabegron in overactive bladder patients: efficacy review and update on drug safety. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2016; 7:204–216. PMID: 27695622.

7. Kim TH, Jung W, Suh YS, Yook S, Sung HH, Lee KS. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of tolterodine 2 mg and 4 mg combined with an α-blocker in men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. BJU Int. 2016; 117:307–315. PMID: 26305143.

8. MacDiarmid S, Al-Shukri S, Barkin J, Fianu-Jonasson A, Grise P, Herschorn S, et al. Mirabegron as add-on treatment to solifenacin in patients with incontinent overactive bladder and an inadequate response to solifenacin monotherapy. J Urol. 2016; 196:809–818. PMID: 27063854.

9. Lucas MG, Bosch RJ, Burkhard FC, Cruz F, Madden TB, Nambiar AK, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on assessment and nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence. Actas Urol Esp. 2013; 37:199–213. PMID: 23452548.

10. Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, Jumadilova Z, Alvir J, Hussein M, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int. 2010; 105:1276–1282. PMID: 19912188.

11. Risacher SL, McDonald BC, Tallman EF, West JD, Farlow MR, Unverzagt FW, et al. Association between anticholinergic medication use and cognition, brain metabolism, and brain atrophy in cognitively normal older adults. JAMA Neurol. 2016; 73:721–732. PMID: 27088965.

12. Khullar V, Chapple C, Gabriel Z, Dooley JA. The effects of antimuscarinics on health-related quality of life in overactive bladder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology. 2006; 68(2 Suppl):38–48.

13. Veenboer PW, Bosch JL. Long-term adherence to antimuscarinic therapy in everyday practice: a systematic review. J Urol. 2014; 191:1003–1008. PMID: 24140548.

14. Chapple CR, Kaplan SA, Mitcheson D, Blauwet MB, Huang M, Siddiqui E, et al. Mirabegron 50 mg once-daily for the treatment of symptoms of overactive bladder: an overview of efficacy and tolerability over 12 weeks and 1 year. Int J Urol. 2014; 21:960–967. PMID: 25092441.

15. Ochodnicky P, Uvelius B, Andersson KE, Michel MC. Autonomic nervous control of the urinary bladder. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2013; 207:16–33. PMID: 23033838.

16. Coyne KS, Matza LS, Kopp Z, Abrams P. The validation of the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC): a single-item global measure for patients with overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2006; 49:1079–1086. PMID: 16460875.

Fig. 2

Change of patient perception of bladder condition and frequency after monotherapy and add-on therapy.

Table 1

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics (n=30)

Table 2

Baseline difference between patients with improved and stationary symptom

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download