Abstract

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common and chronic condition that impacts patients' daily activities and quality of life. Pharmaco-therapy for OAB is a mainstay of treatment. Antimuscarinics and β3-adrenoceptor agonists are the two major classes of oral pharmacotherapy and have similar efficacy for treating the symptoms of OAB. Owing to the chronic nature of OAB, long-term use of medication is essential for OAB symptom control and positive health outcomes. However, many patients elect to stop their medications during the treatment period. Unmet expectations of treatment and side effects seem to be the major factors for discontinuing OAB pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, the short- and long-term persistence and compliance with medication management are markedly worse in OAB than in other chronic medical conditions. Improvement in persistence and compliance with OAB pharmacotherapy is a hot topic in OAB treatment and should be an important goal in the treatment of OAB. Effective strategies should be identified to improve persistence and compliance. In this review, we outline what is known about persistence and compliance and the factors affecting persistence with pharmacotherapy in patients with OAB.

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a symptom-driven condition characterized by urinary urgency with or without urgency urinary incontinence and is usually associated with increased daytime frequency and nocturia [1]. Several epidemiologic studies in Europe, Canada, the United States, and Japan have shown OAB syndrome to be present in 8.0% to 16.5% of adults, with similar rates between men and women [2345]. A population-based survey conducted in Korea demonstrated that the overall prevalence of OAB is 12.2% in the general population over the age of 18 years (10.0% of men and 14.3% of women) [6]. The prevalences of OAB as reported in several population-based studies are briefly summarized in Table 1.

OAB is a heterogeneous condition with a multifactorial underlying pathophysiology that is not yet completely understood [7]. OAB is responsible for a considerable disease burden in terms of detrimental effects on quality of life and high socioeconomic burden. Patients with OAB have more urinary tract infections, skin infections, and sleep disturbances and are at greater risk of falls and fractures [89]. OAB symptoms are associated with serious negative effects on activities of daily living and emotional well-being, work productivity, and social relationships [1011]. Patients with OAB tend to have low self-esteem and to isolate themselves. Moreover, the symptom of urge incontinence increases the risks of hospitalization and admission to a nursing home and may contribute to depression [41213]. Therefore, the goal of OAB management is to reduce the occurrence and severity of OAB symptoms to improve quality of life.

The treatment of OAB is usually started with behavioral therapies [14]. If behavioral therapies are not effective or are only partially effective, oral pharmacotherapy, such as muscarinic receptor antagonists (antimuscarinics) and β3-adrenoceptor agonists, can be offered as a second-line therapy. Because of the chronic nature of OAB, long-term use of OAB medication is related to positive health outcomes and a decrease in health care resource use. As with many chronic conditions that require long-term medication, good persistence and compliance with OAB medication is essential for pharmacotherapy to be beneficial. Thus, patients' persistence and compliance during the course of pharmacotherapy is a major issue in the treatment of OAB. The following review presents what is known about drug persistence and compliance in OAB and the factors influencing medication-taking in OAB.

The concepts of drug persistence and compliance are multidimensional. The terms persistence, compliance, and adherence are used across different therapeutic areas and have been defined in various ways. Thus, there is immense confusion over the use of the terms related to this subject. Because of this lack of uniformity in the definitions of the concepts of drug persistence and compliance, health care providers and researchers needed standard and useful definitions. To address these issues, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Medication Compliance and Persistence Work Group developed definitions for drug persistence and compliance [15]. Although conceptually similar, medication persistence and compliance are two different constructs. Medication persistence refers to the duration of drug therapy, whereas medication compliance refers to the intensity of drug use during the duration of therapy.

Medication persistence is generally used to refer the act of continuing the treatment for the prescribed duration without exceeding a permissible gap [15]. Persistence can also be defined as the overall duration of time from initiation to discontinuation of therapy. By definition, persistence is commonly reported as a dichotomous variable as being "persistent" or "nonpersistent." It can also be reported as a continuous variable, such as the number of days for which therapy was available. On the other hand, the discontinuation rate refers to the proportion of patients who stop taking a treatment.

Medication compliance refers to the act of conforming to the recommendations about day-to-day treatment as prescribed in terms of timing, dosage, and frequency of medication-taking [15]. It may be defined as the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen. Compliance is measured as administered doses per defined period of time and is commonly reported as a percentage. Many different methods are used to assess compliance with medications. Although there is no standardized method, the medication possession ratio is a common measure. The medication possession ratio is calculated as the sum of the days with a supply of any prescribed drug divided by the total days followed up, with at least 80% often indicating good compliance [1617]. Adherence is a synonym of compliance. The term adherence emphasizes the importance of the role of the patient in defining and actively engaging in their treatments to decide whether to adhere to the prescriber's recommendation rather than passively following the prescriber's orders [18]. However, there is no reliable evidence for the assumption that adherence is a superior term or is preferred by patients, and there is also a concern that adherence seems too sticky a concept [1519]. Therefore, compliance continues to be the more popular term.

Regardless of which term is preferred, it is obvious that the maximal benefit of the available medication will be achieved if patients follow the prescriber's recommendation appropriately and closely. As noted above, persistence and compliance are the preferred terms and we will thus use them here to avoid further confusion.

Several studies clearly demonstrate an increasing incidence of OAB over time as well as a persistence of symptoms that illustrates the chronic nature of this disease. The severity of OAB symptoms progresses dynamically over long time periods, such as the progression in OAB symptoms from OAB dry to OAB wet [202122]. Moreover, there is no authoritative evidence that pharmacological therapy can correct the underlying pathophysiology of OAB. Thus, OAB may require long-term treatment to achieve reliable control of symptoms [23]. Actually, Rogers et al. [24] reported that patients who received tolterodine for 6 months showed continuous improvement in voiding diary parameters compared with those who received the medication for only 3 months.

In most cases, OAB symptoms relapse after discontinuation of pharmacotherapy. Discontinuation of OAB treatment often results in retreatment. For example, Choo et al. [25] reported that discontinuation of OAB medication after successful treatment for 12 weeks led to the recurrence of OAB symptoms in many patients. In their study, most patients showed recurring frequency and urgency that became bothersome, as evidenced by the high retreatment rate and the decreasing satisfaction rate at 16 weeks. According to Lee et al. [26], discontinuation of tolterodine after successful treatment led to a recurrence of OAB symptoms in 67% of patients, resulting in a high retreatment rate of 65% within 3 months, irrespective of treatment periods.

Recently, Kim et al. [27] reported that good persistence of OAB medication was associated with greater symptom improvement and increased quality of life. Improvements in scores on the OAB symptom questionnaire and the OABquestionnaire short form were significantly greater in patients who were persistent with antimuscarinics than in those who were nonpersistent with antimuscarinics. This means that patients who were persistent with OAB medication experienced fewer symptoms from OAB and had a higher quality of life during their pharmacotherapy.

In chronic conditions requiring long-term and consistent pharmacotherapy, medication persistence and compliance are critical predictors of treatment outcomes. Furthermore, patients with poor persistence and compliance with pharmacotherapy are at a higher risk for morbidity and mortality and for increased health care costs compared with patients with good persistence and compliance [28]. Like other chronic diseases, OAB typically requires good persistence and compliance with pharmacotherapy [29].

Currently, oral pharmacotherapy is a mainstay of OAB treatment. The two major classes of oral pharmacotherapy for treating the symptoms of OAB are antimuscarinics and β3-adrenoceptor agonists. Among them, the principal drugs used for relieving OAB symptoms are antimuscarinics. Numerous antimuscarinics are currently available that are highly effective for patients of all ages with OAB [7].

Persistence of drug therapy is typically low in many chronic diseases [30], but the persistence seen with antimuscarinics in OAB appears to be markedly poorer than for other types of chronic medications, such as statins, osteoporosis drugs, antidiabetic drugs, and antihypertensive drugs. Medication persistence and compliance are diverse with respect to type of antimuscarinics, formulations and dosing, study designs, and study duration. All of these factors may affect rates of persistence and compliance, and trends reported must be interpreted within the context of these variables.

Several randomized double-blind clinical trials have demonstrated that 6% to 31% of OAB patients prematurely discontinued their antimuscarinics after 12 weeks of therapy [31323334353637383940]. Generally, there was a tendency toward an increase in discontinuation rates during the longer follow-up periods. According to the type of antimuscarinics, rates of discontinuation for 12 weeks were 7% to 19% of those taking tolterodine, 13% to 31% of those taking oxybutynin, 6% to 9% of those taking solifenacin, and 14% to 20% of those taking fesoterodine. In randomized open-label or openlabel extension studies, the rates of discontinuation were somewhat higher and showed higher rates with longer follow-up periods. In these studies, overall discontinuation rates were 10% to 67% of those taking antimuscarinics with various follow-up durations [41424344].

In retrospective medical claims studies, rates of discontinuation are markedly higher than what has been reported in clinical trials. In a systematic review of medical claims studies, persistence began to fall off within the first prescription period, and rates of discontinuation of antimuscarinics were 43% to 83% within the first 30 days [16174546]. Based on claims from a Medicaid population from California, Yu et al. [16] found that 88.6% of patients with chronic OAB discontinued their pharmacotherapy after a median of 50 days during a 12-month study. Shaya et al. [47] also found that the 12-month persistence rates were 5% to 9% in Medicaid patients prescribed antimuscarinics. A similar pattern was noted for persistence in treatment-naïve patients. In a retrospective cohort study of those aged 66 years and above who were newly prescribed either oxybutynin or tolterodine conducted in Canada [48], persistence on oxybutynin and tolterodine was 18.9% and 27.3% at 12 months, respectively. After 2 years of followup, persistence was 9.4% and 16.9% for oxybutynin and tolterodine, respectively. In a retrospective study based on real prescription data from the United Kingdom [49], 65% to 86% of patients discontinued their initial antimuscarinics at 12 months regardless of types of antimuscarinics.

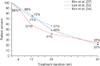

Several studies have described persistence of antimuscarinics on the basis of real clinical practice. Medication persistence in real clinical practice may be substantially different from that in clinical trials. Persistence to treatments is often better in clinical trials than it is in real clinical practice. In a clinical trial setting, patients may be more motivated and cooperative with their prescribed recommendations than they are otherwise. On the other hand, studies conducted in real clinical practice have high external validity and allow greater generalization than clinical trials. In one study, Dmochowski and Newman [50] reported that approximately 53% had been taking their medication for 1 year or longer in a self-administered survey of volunteers to serve in an online research panel, and just 32% of participants were completely satisfied with their current medications. In a postal-based survey conducted in the United States, 24.5% of patients who had been prescribed antimuscarinics for OAB reported that they had discontinued one or more antimuscarinic prescription medications during the previous 12 months [29]. In other open-label observational studies, the rates of medication discontinuation in 12 months were 21% to 78% of those taking antimuscarinics [2751525354]. In a multicenter, prospective, and observational study conducted in Korea [27], 56.8% of patients with OAB remained on their antimuscarinics at 24 weeks. The persistence at 4 and 12 weeks was 85.6% and 71.4%, respectively. Among those who were persistent to their antimuscarinics, compliance with the medication was 75.6%, 53.8%, and 34.3% after 4, 12, and 24 weeks, respectively. Lee et al. [53] reported that only 25% of men with benign prostatic obstruction and OAB remained on their solifenacin add-on therapy after tamsulosin monotherapy within one year in a real clinical environment. Kim et al. [54] also reported that 1-year persistence on solifenacin was 22.1% in a prospective, multicenter, observational study conducted in Korea. In their study, persistence at 12, 24, and 36 weeks was 72.4%, 45.8%, and 31.1%, respectively. In addition, the compliance among patients who were persistent to their solifenacin treatment was 94.1% at 1 year. Fig. 1 shows the trend of persistence of antimuscarinics in three observational studies conducted in Korea.

Although antimuscarinics are the cornerstone pharmacotherapy for OAB, they usually give rise to anticholinergic adverse events, such as dry mouth and constipation, which may be one of the major factors leading to poor persistence with these medications. More recently, the introduction of mirabegron, the first commercially available β3-adrenoceptor agonist for the treatment of OAB, has widened the therapeutic options for the management of OAB [55]. Mirabegron is well known to have a mechanism of action and side-effect profile different from that of antimuscarinics. In a systematic review including numerous randomized controlled trials, mirabegron was as efficacious as antimuscarinics in reducing the storage symptoms of OAB, but had a side-effect profile similar to that of placebo [56]. In a retrospective analysis conducted at a single center based on real clinical practice, persistence with mirabegron for OAB at 3 months was 69% and fell to 48% by 6 months [57]. In a retrospective medical claims study from a Canadian database [58], persistence in OAB patients prescribed either mirabegron or other antimuscarinics was compared over 12 months. Patients who were prescribed mirabegron remained on their pharmacotherapy longer than did those who received antimuscarinics. The median numbers of days on mirabegron in the treatment-naïve cohort and treatment-experienced cohort were 196 and 299 days, respectively. A similar pattern was observed in patients who were prescribed the different antimuscarinics. The median numbers of days in the treatment-naïve and treatmentexperienced cohort were 70 to 100 days and 96 to 242 days, respectively. In the treatment-naïve cohort, persistence at 12 months was 29.9% with mirabegron, compared with 13.8% to 21.0% with antimuscarinics. Furthermore, patients taking mirabegron demonstrated significantly higher compliance than did those taking antimuscarinics (64.5% for mirabegron vs. 18.6% to 49.2% for the various antimuscarinics). Individual studies that evaluated the medication-taking status of oral pharmacotherapy for OAB are briefly summarized in Table 2.

The reasons underlying the low rates of persistence for OAB pharmacotherapy in clinical practice are diverse. Personal, clinical, and environmental factors can influence patients' persistence and compliance with OAB pharmacotherapy, regardless of causes. It seems likely that discontinuation is affected by many factors, including adverse events, unmet expectations of treatment, and recognition by patients of the chronic nature of their symptoms [58]. Sometimes, many patients discontinue their OAB pharmacotherapy before the full therapeutic effects have been established. Persistence rates vary between antimuscarinics; although this may be partly linked to differences in efficacy and tolerability, persistence is generally better with extended-release and once-daily formulations [164759]. In the study by Shaya et al. [47], only 32% of patients taking an oxybutynin immediate-release formulation persisted with the medication after 30 days. On the other hand, 44% of patients taking either long-acting tolterodine extended-release and oxybutynin extendedrelease persisted with the medication for longer than 30 days. Several studies have found that older patients are more likely than younger patients to persist in taking OAB pharmacotherapy [2747495458]. Female sex also can be a risk factor for discontinuation of OAB pharmacotherapy [5458].

A survey conducted in the United State in 2005 examined reasons for discontinuing OAB pharmacotherapy [60]. In this survey, the most important considerations in discontinuing medication for most patients were ef fectiveness and side ef fects. The most commonly reported reason for discontinuing treatment was unmet treatment expectations (46.2%). Many patients (21.1%) were discontinuing OAB medication primarily because of side effects. These findings suggest that clinicians should be familiar with identifying and managing patients' unmet expectations. In addition, assessing goal achievement for the most bothersome symptoms might be able to enhance persistence and compliance by promoting realistic expectations about treatment efficacy and side effects. A support program may also improve persistence and compliance for OAB pharmacotherapy by providing patients with educational materials about the nature of OAB and advice about the importance of taking their medication as recommended. Klutke et al. [61] suggests that the addition of focused, written behavioral intervention to antimuscarinics might enhance improvements in OAB symptoms and treatment satisfaction in those who are dissatisfied with antimuscarinics. Wyman et al. [62] also suggest behavioral intervention and lifestyle modification, which can be used as an adjunct therapy to enhance pharmacotherapy for OAB.

The successful treatment of OAB is mainly related to medication persistence and compliance, which is affected by several factors, such as inadequate efficacy and bothersome side effects. In general, persistence and compliance with antimuscarinic medication for OAB are poor. Although the available studies are limited, mirabegron is somewhat associated with higher levels of persistence with OAB treatment than the antimuscarinics. For optimal outcomes of OAB pharmacotherapy, improved persistence is an important goal in the treatment of OAB. Improving persistence and compliance with OAB pharmacotherapy is a challenge for both patients and clinicians. Assessing the individualized needs of each patient and goal achievement for the most bothersome symptoms as well as patient support programs can be good strategies to improve persistence and compliance with OAB pharmacotherapy. What we need today are efforts to find more effective and promising strategies for improving persistence and compliance with OAB pharmacotherapy. This would go along with addressing patients' expectations and effectively managing OAB symptoms and improving patients' quality of life.

Figures and Tables

Table 1

The prevalence of overactive bladder in conducted population-based studies

| Variable | Korea [6] | Finland [2] | Europe and Canada [3] | United States [4] | Japan [5] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of respondents | 2,000 | 3,727 | 19,165 | 5,204 | 4,570 |

| Response rate (%) | 22.1 | 62.4 | 33.0 | 44.3 | 45.3 |

| Age distribution (y) | ≥18 | 18-79 | ≥18 | ≥18 | 40-100 |

| Survey method | Telephone survey | Postal survey | Telephone survey | Telephone survey | Postal survey |

| Prevalence of OAB (%) | |||||

| Men | 10.0 | 6.5 | 10.8 | 16.0 | 14.0 |

| Women | 14.3 | 9.3 | 12.8 | 16.9 | 11.0 |

| Overall | 12.2 | 8.0 | 11.8 | 16.5 | 12.4 |

Table 2

Summary of studies on the medication-taking status of overactive bladder patients

| Study | Study design | Drug | No. | Outcome measurement | Length of follow-up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrams et al. [31] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | 150 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | 11.3% |

| Rogers et al. [32] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | 201 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | 18.9% |

| Cardozo et al. [33] | Randomized controlled study | Solifenacin | 576 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | 7.6% |

| Nitti et al. [34] | Randomized controlled study | Fesoterodine | 562 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | 20.3% |

| Drutz et al. [35] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 109 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 12.8% |

| Oxybutynin | Oxybutynin: 112 | Oxybutynin: 31.3% | ||||

| Homma et al. [36] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 240 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 10.4% |

| Oxybutynin | Oxybutynin: 246 | Oxybutynin: 23.2% | ||||

| Armstrong et al. [37] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 399 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 10.5% |

| Oxybutynin | Oxybutynin: 391 | Oxybutynin: 13.3% | ||||

| Chapple et al. [38] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 263 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 9.9% |

| Solifenacin | Solifenacin: 547 | Solifenacin: 8.6% | ||||

| Chapple et al. [39] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 599 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 7.3% |

| Solifenacin | Solifenacin: 578 | Solifenacin: 5.9% | ||||

| Chapple et al. [40] | Randomized controlled study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 290 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 12.8% |

| Fesoterodine | Fesoterodine: 559 | Fesoterodine: 13.8% | ||||

| Giannitsas et al. [41] | Randomized open-label study | Tolterodine | 128 | Discontinuation rate | 6 Weeks | 16.4% |

| Oxybutynin | ||||||

| Sand et al. [42] | Randomized open-label study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 163 | Discontinuation rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine: 10.4% |

| Oxybutynin | Oxybutynin: 152 | Oxybutynin: 14.5% | ||||

| Salvatore et al. [43] | Randomized open-label study | Oxybutynin | 66 | Discontinuation rate | 2 Years | 66.7% |

| Abrams et al. [44] | Open-label extension study | Tolterodine | 714 | Discontinuation rate | 52 Weeks | 38.2% |

| Yu et al. [16] | Retrospective medical claims study | OAB medication | 2,415 | Discontinuation rate | 52 Weeks | Discontinuation rate: 88.6% |

| Compliance rate | Compliance rate : 0.7% | |||||

| Shaya et al. [47] | Retrospective medical claims study | Tolterodine or oxybutynin | 1,637 | Persistence rate | 52 Weeks | Tolterodine ER: 9% |

| Oxybutynin ER: 6%; Oxybutynin IR: 5% | ||||||

| Gomes et al. [48] | Retrospective medical claims study | Tolterodine | Tolterodine: 24,855 | Persistence rate | 52 Weeks | Tolterodine: 27.3% |

| Oxybutynin | Oxybutynin: 31,996 | Oxybutynin: 18.9% | ||||

| 2 Years | Tolterodine: 13.6% | |||||

| Oxybutynin: 9.4% | ||||||

| Wagg et al. [58] | Retrospective medical claims study | Mirabegron | 1,683 | Persistence rate | 52 Weeks | Persistence rate: 31.7% |

| Compliance rate | Compliance rate: 64.5% | |||||

| Wagg et al. [49] | Retrospective study | Tolterodine | 4,833 | Persistence rate | 12 Weeks | Tolterodine ER: 47%; Tolterodine IR: 46% |

| Solifenacin | Solifenacin: 58% | |||||

| Oxybutynin | Oxybutynin ER: 44%; Oxybutynin IR: 40% | |||||

| Propiverine | Propiverine: 47% | |||||

| Trospium | Trospium: 42% | |||||

| Darifenacin | Darifenacin: 52% | |||||

| Flavoxate | Flavoxate: 28% | |||||

| 24 Weeks | Tolterodine ER: 36% Tolterodine IR: 33% | |||||

| Solifenacin: 46% | ||||||

| Oxybutynin ER: 35%; Oxybutynin IR: 29% | ||||||

| Propiverine: 36% | ||||||

| Trospium: 33% | ||||||

| Darifenacin: 30% | ||||||

| Flavoxate: 16% | ||||||

| 52 Weeks | Tolterodine ER: 28% Tolterodine IR: 24% | |||||

| Solifenacin: 35% | ||||||

| Oxybutynin ER: 26%; Oxybutynin IR: 22% | ||||||

| Propiverine: 27% | ||||||

| Trospium: 26% | ||||||

| Darifenacin: 17% | ||||||

| Flavoxate: 14% | ||||||

| Pindoria et al. [57] | Retrospective study | Mirabegron | 197 | Persistence rate | 12 Weeks | 69% |

| 24 Weeks | 48% | |||||

| Diokno et al. [51] | Open-label study | Oxybutynin | 1,067 | Discontinuation rate | 52 Weeks | 53.8% |

| Homma et al. [52] | Open-label study | Imidafenacin | 478 | Discontinuation rate | 52 Weeks | 21.3% |

| Lee et al. [53] | Prospective, observational study | Solifenacin | 176 | Persistence rate | 12 Weeks | 56.8% |

| 24 Weeks | 40.9% | |||||

| 52 Weeks | 25.0% | |||||

| Kim et al. [27] | Prospective, observational study | Any antimuscarinics | 952 | Persistence rate Compliance rate | 4 Weeks | Persistence rate: 85.6% |

| Compliance rate: 75.6% | ||||||

| 12 Weeks | Persistence rate: 71.4% | |||||

| Compliance rate: 53.8% | ||||||

| 24 Weeks | Persistence rate: 56.8% | |||||

| Compliance rate: 34.3% | ||||||

| Kim et al. [54] | Prospective, observational study | Solifenacin | 1018 | Persistence rate | 12 Weeks | Persistence rate: 72.4% |

| Compliance rate | ||||||

| 24 Weeks | Persistence rate: 45.8% | |||||

| 36 Weeks | Persistence rate: 31.1% | |||||

| 52 Weeks | Persistence rate: 22.1% | |||||

| Compliance rate: 94.1% |

References

1. Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010; 21:5–26.

2. Tikkinen KA, Tammela TL, Rissanen AM, Valpas A, Huhtala H, Auvinen A. Is the prevalence of overactive bladder overestimated? A population-based study in Finland. PLoS One. 2007; 7(2):e195.

3. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, Reilly K, Kopp Z, Herschorn S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006; 50:1306–1314.

4. Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, Abrams P, Herzog AR, Corey R, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003; 20:327–336.

5. Homma Y, Yamaguchi O, Hayashi K. Neurogenic Bladder Society Committee. An epidemiological survey of overactive bladder symptoms in Japan. BJU Int. 2005; 96:1314–1318.

6. Lee YS, Lee KS, Jung JH, Han DH, Oh SJ, Seo JT, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder, urinary incontinence, and lower urinary tract symptoms: results of Korean EPIC study. World J Urol. 2011; 29:185–190.

7. Chapple CR, Khullar V, Gabriel Z, Muston D, Bitoun CE, Weinstein D. The effects of antimuscarinic treatments in overactive bladder: an update of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2008; 54:543–562.

8. Brown JS, McGhan WF, Chokroverty S. Comorbidities associated with overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2000; 6:11 Suppl. S574–S579.

9. Wagner TH, Hu TW, Bentkover J, LeBlanc K, Stewart W, Corey R, et al. Health-related consequences of overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2002; 8:19 Suppl. S598–S607.

10. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Kopp Z, Abrams P, Cardozo L. Impact of overactive bladder symptoms on employment, social interactions and emotional well-being in six European countries. BJU Int. 2006; 97:96–100.

11. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, Ebel-Bitoun C, Milsom I, Chapple C. The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health-related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2011; 108:1459–1471.

12. Thom DH, Haan MN, Van Den Eeden SK. Medically recognized urinary incontinence and risks of hospitalization, nursing home admission and mortality. Age Ageing. 1997; 26:367–374.

13. Lee YI, Kim JW, Bae SR, Paick SH, Kim KW, Kim HG, et al. Effect of urgency symptoms on the risk of depression in community-dwelling elderly men. Korean J Urol. 2013; 54:762–766.

14. Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, Chai TC, Clemens JQ, Culkin DJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. J Urol. 2012; 188:6 Suppl. 2455–2463.

15. Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollen-dorf DA, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008; 11:44–47.

16. Yu YF, Nichol MB, Yu AP, Ahn J. Persistence and adherence of medications for chronic overactive bladder/urinary incontinence in the california medicaid program. Value Health. 2005; 8:495–505.

17. Sexton CC, Notte SM, Maroulis C, Dmochowski RR, Cardozo L, Subramanian D, et al. Persistence and adherence in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome with anticholinergic therapy: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract. 2011; 65:567–585.

18. Lutfey KE, Wishner WJ. Beyond "compliance" is "adherence". Improving the prospect of diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 1999; 22:635–639.

19. Feinstein AR. On white-coat effects and the electronic monitoring of compliance. Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:1377–1378.

20. Irwin DE, Milsom I, Chancellor MB, Kopp Z, Guan Z. Dynamic progression of overactive bladder and urinary incontinence symptoms: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2010; 58:532–543.

21. Malmsten UG, Molander U, Peeker R, Irwin DE, Milsom I. Urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms: a longitudinal population-based survey in men aged 45-103 years. Eur Urol. 2010; 58:149–156.

22. Wennberg AL, Molander U, Fall M, Edlund C, Peeker R, Milsom I. A longitudinal population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in women. Eur Urol. 2009; 55:783–791.

23. Abrams P, Kelleher CJ, Kerr LA, Rogers RG. Overactive bladder significantly affects quality of life. Am J Manag Care. 2000; 6:11 Suppl. S580–S590.

24. Rogers RG, Omotosho T, Bachmann G, Sun F, Morrow JD. Continued symptom improvement in sexually active women with overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence treated with tolterodine ER for 6 months. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009; 20:381–385.

25. Choo MS, Song C, Kim JH, Choi JB, Lee JY, Chung BS, et al. Changes in overactive bladder symptoms after discontinuation of successful 3-month treatment with an antimuscarinic agent: a prospective trial. J Urol. 2005; 174:201–204.

26. Lee YS, Choo MS, Lee JY, Oh SJ, Lee KS. Symptom change after discontinuation of successful antimuscarinic treatment in patients with overactive bladder symptoms: a randomised, multicentre trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2011; 65:997–1004.

27. Kim TH, Choo MS, Kim YJ, Koh H, Lee KS. Drug persistence and compliance affect patient-reported outcomes in overactive bladder syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2015; 12. 24. DOI: 10.1007/s11136-015-1216-z.

28. Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B. Medication adherence and persistence: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2005; 22:313–356.

29. Schabert VF, Bavendam T, Goldberg EL, Trocio JN, Brubaker L. Challenges for managing overactive bladder and guidance for patient support. Am J Manag Care. 2009; 15:4 Suppl. S118–S122.

30. Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, Sian S, Smith DB. Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009; 15:728–740.

31. Abrams P, Kaplan S, De Koning Gans HJ, Millard R. Safety and tolerability of tolterodine for the treatment of overactive bladder in men with bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2006; 175(3 Pt 1):999–1004.

32. Rogers R, Bachmann G, Jumadilova Z, Sun F, Morrow JD, Guan Z, et al. Efficacy of tolterodine on overactive bladder symptoms and sexual and emotional quality of life in sexually active women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008; 19:1551–1557.

33. Cardozo L, Lisec M, Millard R, van Vierssen Trip O, Kuzmin I, Drogendijk TE, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial of the once daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin succinate in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol. 2004; 172(5 Pt 1):1919–1924.

34. Nitti VW, Dmochowski R, Sand PK, Forst HT, Haag-Molken-teller C, Massow U, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of fesoterodine for overactive bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2007; 178:2488–2494.

35. Drutz HP, Appell RA, Gleason D, Klimberg I, Radomski S. Clinical efficacy and safety of tolterodine compared to oxybutynin and placebo in patients with overactive bladder. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1999; 10:283–289.

36. Homma Y, Paick JS, Lee JG, Kawabe K. Japanese and Korean Tolterodine Study Group. Clinical efficacy and tolerability of extended-release tolterodine and immediate-release oxybutynin in Japanese and Korean patients with an overactive bladder: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. BJU Int. 2003; 92:741–747.

37. Armstrong RB, Luber KM, Peters KM. Comparison of dry mouth in women treated with extended-release formulations of oxybutynin or tolterodine for overactive bladder. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005; 37:247–252.

38. Chapple CR, Rechberger T, Al-Shukri S, Meffan P, Everaert K, Huang M, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo- and tolterodine-controlled trial of the once-daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin in patients with symptomatic overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2004; 93:303–310.

39. Chapple CR, Martinez-Garcia R, Selvaggi L, Toozs-Hobson P, Warnack W, Drogendijk T, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of solifenacin succinate and extended release tolterodine at treating overactive bladder syndrome: results of the STAR trial. Eur Urol. 2005; 48:464–470.

40. Chapple C, Van Kerrebroeck P, Tubaro A, Haag-Molkenteller C, Forst HT, Massow U, et al. Clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability of once-daily fesoterodine in subjects with overactive bladder. Eur Urol. 2007; 52:1204–1212.

41. Giannitsas K, Perimenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Gyftopoulos K, Nikiforidis G, Barbalias G. Comparison of the efficacy of tolterodine and oxybutynin in different urodynamic severity grades of idiopathic detrusor overactivity. Eur Urol. 2004; 46:776–782.

42. Sand PK, Miklos J, Ritter H, Appell R. A comparison of extended-release oxybutynin and tolterodine for treatment of overactive bladder in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004; 15:243–248.

43. Salvatore S, Khullar V, Cardozo L, Milani R, Athanasiou S, Kelleher C. Long-term prospective randomized study comparing two different regimens of oxybutynin as a treatment for detrusor overactivity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005; 119:237–241.

44. Abrams P, Malone-Lee J, Jacquetin B, Wyndaele JJ, Tammela T, Jonas U, et al. Twelve-month treatment of overactive bladder: efficacy and tolerability of tolterodine. Drugs Aging. 2001; 18:551–560.

45. Desgagne A, LeLorier J. Incontinence drug utilization patterns in Québec, Canada. Value Health. 1999; 2:452–458.

46. Malone DC, Okano GJ. Treatment of urge incontinence in Veterans Affairs medical centers. Clin Ther. 1999; 21:867–877.

47. Shaya FT, Blume S, Gu A, Zyczynski T, Jumadilova Z. Persistence with overactive bladder pharmacotherapy in a Medicaid population. Am J Manag Care. 2005; 11:4 Suppl. S121–S129.

48. Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM. Comparative adherence to oxybutynin or tolterodine among older patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012; 68:97–99.

49. Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, Siddiqui E. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU Int. 2012; 110:1767–1774.

50. Dmochowski RR, Newman DK. Impact of overactive bladder on women in the United States: results of a national survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007; 23:65–76.

51. Diokno A, Sand P, Labasky R, Sieber P, Antoci J, Leach G, et al. Long-term safety of extended-release oxybutynin chloride in a community-dwelling population of participants with overactive bladder: a one-year study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002; 34:43–49.

52. Homma Y, Yamaguchi O. Long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of the novel anti-muscarinic agent imidafenacin in Japanese patients with overactive bladder. Int J Urol. 2008; 15:986–991.

53. Lee YS, Lee KS, Kim JC, Hong S, Chung BH, Kim CS, et al. Persistence with solifenacin add-on therapy in men with benign prostate obstruction and residual symptoms of overactive bladder after tamsulosin monotherapy. Int J Clin Pract. 2014; 68:1496–1502.

54. Kim TH, You HW, Park JH, Lee JG, Choo MS, Park WH. Persistence of solifenacin therapy in patients with overactive bladder in the clinical setting: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Int J Clin Pract Forthcoming 2016.

55. Chapple CR, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, Siddiqui E, Michel MC. Mirabegron in overactive bladder: a review of efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014; 33:17–30.

56. Maman K, Aballea S, Nazir J, Desroziers K, Neine ME, Siddiqui E, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of medical treatments for the management of overactive bladder: a systematic literature review and mixed treatment comparison. Eur Urol. 2014; 65:755–765.

57. Pindoria N, Malde S, Nowers J, Taylor C, Kelleher C, Sahai A. Persistence with mirabegron therapy for overactive bladder: A real life experience. Neurourol Urodyn. 2015; 12. 15. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22943.

58. Wagg A, Franks B, Ramos B, Berner T. Persistence and adherence with the new beta-3 receptor agonist, mirabegron, versus antimuscarinics in overactive bladder: early experience in Canada. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015; 9:343–350.

59. D'Souza AO, Smith MJ, Miller LA, Doyle J, Ariely R. Persistence, adherence, and switch rates among extended-release and immediate-release overactive bladder medications in a regional managed care plan. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008; 14:291–301.

60. Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, Jumadilova Z, Alvir J, Hussein M, et al. Patient-reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int. 2010; 105:1276–1282.

61. Klutke CG, Burgio KL, Wyman JF, Guan Z, Sun F, Berriman S, et al. Combined effects of behavioral intervention and tolterodine in patients dissatisfied with overactive bladder medication. J Urol. 2009; 181:2599–2607.

62. Wyman JF, Burgio KL, Newman DK. Practical aspects of lifestyle modifications and behavioural interventions in the treatment of overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. Int J Clin Pract. 2009; 63:1177–1191.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download