This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Purpose

Lichen sclerosus (LS) in men is poorly understood. Though uncommon, it is often severe and leads to repeated surgical interventions and deterioration in quality of life. We highlight variability in disease presentation, diagnosis, and patient factors in male LS patients evaluated at a tertiary care center.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed charts of male patients presenting to our reconstructive urology clinic with clinical or pathologic diagnosis of LS between 2004 and 2014. Relevant clinical and demographic information was abstracted and descriptive statistics calculated. Subgroup comparisons were made based on body mass index (BMI), urethral stricture, and pathologic confirmation of disease.

Results

We identified 94 patients with clinical diagnosis of LS. Seventy percent (70%) of patients in this cohort had BMI >30 kg/m2, and average age was 51.5 years. Lower BMI patients were more likely to suffer from urethral stricture disease compared to overweight counterparts (p=0.037). Patients presenting with stricture disease were more likely to be younger (p=0.003). Thirty percent (30%) of this cohort had a pathologic diagnosis of LS.

Conclusions

Urethral stricture is the most common presentation for men with LS. Many patients endure skin scarring and have numerous comorbidities. Patient profile is diverse, raising the concern that not all patients with clinical diagnosis of LS are suffering from identical disease processes. The rate of pathologic confirmation at a tertiary care institution is alarmingly low. Our findings support a role for increased focus on pathologic confirmation and further delineation of the subtype of disease based on location and clinical manifestations.

Go to :

Keywords: Balanitis xerotica obliterans, Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, Urethral stricture

INTRODUCTION

Lichen sclerosus (LS), formerly referred to as balanitis xerotica obliterans, is a chronic inflammatory condition usually affecting the anogenital region. In males, it is classically thought to begin distally at the meatus with phimosis and progresses proximally over time, eventually leading to panurethral sclerosis and urinary obstruction [

1]. Recent data, however, have also identified LS in association with isolated bulbar urethral stricture disease [

2]. In general, it can present with variable involvement of the penile skin, glans, and urethra, though it may also involve the skin at sites of urinary diversion [

3].

Estimates of the prevalence of LS vary from 0.0014% to over 0.01% in adult men, but it may be underreported [

4,

5]. While in practice it is primarily diagnosed clinically, the degree to which clinical diagnosis is consistent with pathologic findings is not well established. Additionally, the etiology of LS is complex and poorly understood. It is believed to be caused through both humoral and cell-mediated autoimmunity, and has been associated with atopy and other autoimmune conditions [

6,

7,

8]. Furthermore LS has been associated with alterations in methylation patterns and gene expression in affected tissue [

9,

10]. These changes in gene expression and chronic inflammation make untreated LS a risk factor for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis [

11]. In addition to these molecular and autoimmune changes, LS has been associated with elevated body mass index (BMI), diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), and smoking, suggesting that the development and pathogenesis of disease may be intertwined with metabolic and microvascular influences that modulate disease progression [

12]. Management of the condition varies widely depending on the location and progression of the disease. Early cases are sometimes managed with topical steroids, while circumcision may be used for disease limited to the glans and foreskin [

13]. Recurrent strictures may be managed with a urethrotomy or urethral dilation, but these are generally not effective long-term solutions. Instead, urethroplasty with grafted tissue is the preferred and more robust solution in these patients [

1,

14,

15,

16].

Overall, the mechanisms of disease initiation and progression remain largely unknown, making it difficult to define the typical patient or prognosis. LS may be diagnosed pathologically or clinically. It is unknown whether the clinical diagnosis of LS correlates with a pathologic diagnosis or if the clinical diagnosis of LS is a more heterogeneous collection of disease processes.

Clinically, there is a great variability among patients carrying the diagnosis of LS. On one hand, there exist young and fit patients with intact genital skin who present with extensive urethral involvement in the presence of minimal penile skin manifesations. On the other hand, the index patient is morbidly obese with buried penis, recurrent fungal infections, and severely scarred genital skin but with a completely intact urethra. Despite the drastic variability, all of these patients are categorically classified as having LS. Given the wide range of disease manifestations and the dearth of understanding regarding LS it is currently quite difficult to accurately predict outcomes and prognosis for patients. A better understanding of how LS alters its behavior in various patient profiles as well as how to best approach the diagnosis of LS could allow for improved discussion with patients and optimized planning for long-term disease management. We aimed to determine the degree of variability among patients with the clinical diagnosis of LS as well as the extent of their urethral involvement in the hope of better categorizing patients into various subgroups with similar disease characteristics. We also sought to determine the rate of pathologic confirmation of the clinical diagnosis of LS.

Go to :

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board to retrospectively review hospital records for all adult male patients with the clinical diagnosis of lichen sclerosis. We queried our reconstructive database and clinic records between January 2004 and March 2014 for the diagnosis of LS as well as other potentially related diagnoses such as phimosis, buried penis, balanitis and urethral stricture. All charts were reviewed and demographic and clinical factors such as age, weight, BMI, surgical procedures, findings on physical exam, pathologic examination, various comorbidities, topical steroid use, laboratory data such as urine analysis findings, pH, specific gravity, and serum inflammatory markers were abstracted. We also reviewed imaging results such as retrograde urethrograms for evaluation of the location of any associated urethral strictures. Of the long list of comorbidities, we collected data for the following: obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, CAD, and dyslipidemia. We evaluated obesity using BMI, categorizing patients 30–34.9 kg/m2 as obese and those over 35 kg/m2 as morbidly obese. Urethral stricture location was categorized as meatal, penile, bulbar, or panurethral. Based on the description by physical exam, we categorized patients as having skin scarring involving meatus, glans, penile skin with or without buried/trapped penis, or scarring at diversion site of perineal urethrostomy.

To be able to identify subgroups with similar clinical and demographic parameters, we compared different groups based on their BMI, presence or absence of urethral strictures, presence or absence of pathologic confirmation of the disease.

Descriptive statistics were then computed for these variables. Continuous variables were summarized by mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables were summarized by frequency of observation. Tests of significance were performed using Student t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests and chi-square tests for categorical variables where appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata ver. 13.1 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX, USA), and a significance level of α=0.05 was used for all significance tests.

Go to :

RESULTS

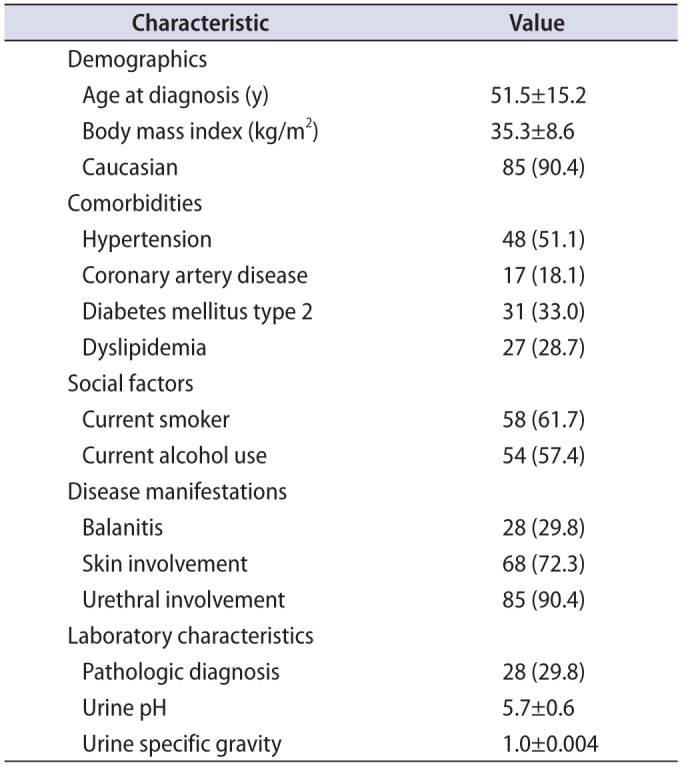

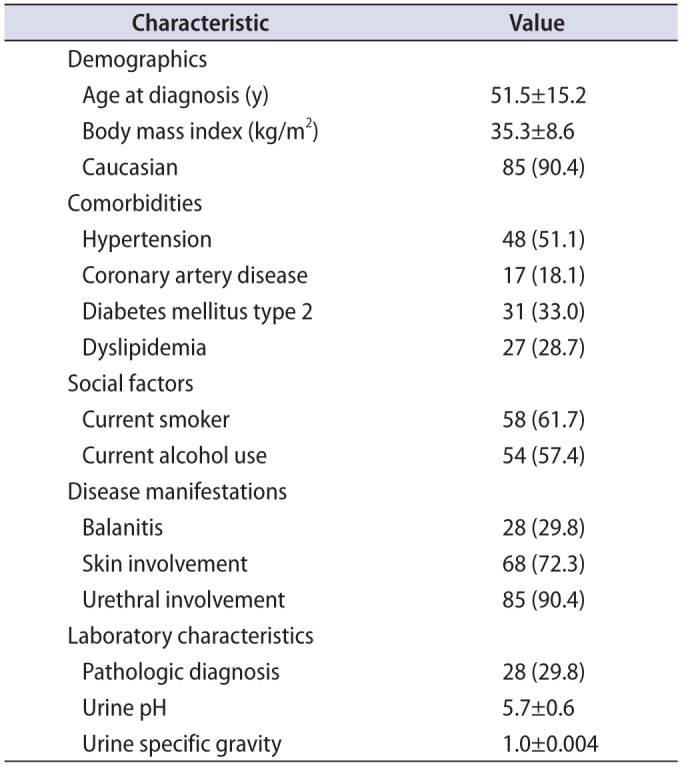

Between 2004 and 2014, we identified 94 patients with clinical diagnosis of LS. The overall demographics and characteristics of our study population are displayed in

Table 1. The average patient in this cohort was middle aged, obese, and Caucasian. Comorbid disease burden was significant in these patients with over half suffering from hypertension (51.1%) along with high rates of type 2 diabetes (33%), dyslipidemia (28.7%), and CAD (18.1%). This study population also had high rates of smoking (61.7%) and alcohol use (57.4%). Urethral involvement was present in 90.4% of patients. Genital skin involvement and balanitis were seen less commonly in our cohort, observed at 72.3% and 29.8%, respectively. The overall rate of penile cancer in this cohort was 7.45%.

Table 1

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics (n=94)

|

Characteristic |

Value |

|

Demographics |

|

|

Age at diagnosis (y) |

51.5±15.2 |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

35.3±8.6 |

|

Caucasian |

85 (90.4) |

|

Comorbidities |

|

|

Hypertension |

48 (51.1) |

|

Coronary artery disease |

17 (18.1) |

|

Diabetes mellitus type 2 |

31 (33.0) |

|

Dyslipidemia |

27 (28.7) |

|

Social factors |

|

|

Current smoker |

58 (61.7) |

|

Current alcohol use |

54 (57.4) |

|

Disease manifestations |

|

|

Balanitis |

28 (29.8) |

|

Skin involvement |

68 (72.3) |

|

Urethral involvement |

85 (90.4) |

|

Laboratory characteristics |

|

|

Pathologic diagnosis |

28 (29.8) |

|

Urine pH |

5.7±0.6 |

|

Urine specific gravity |

1.0±0.004 |

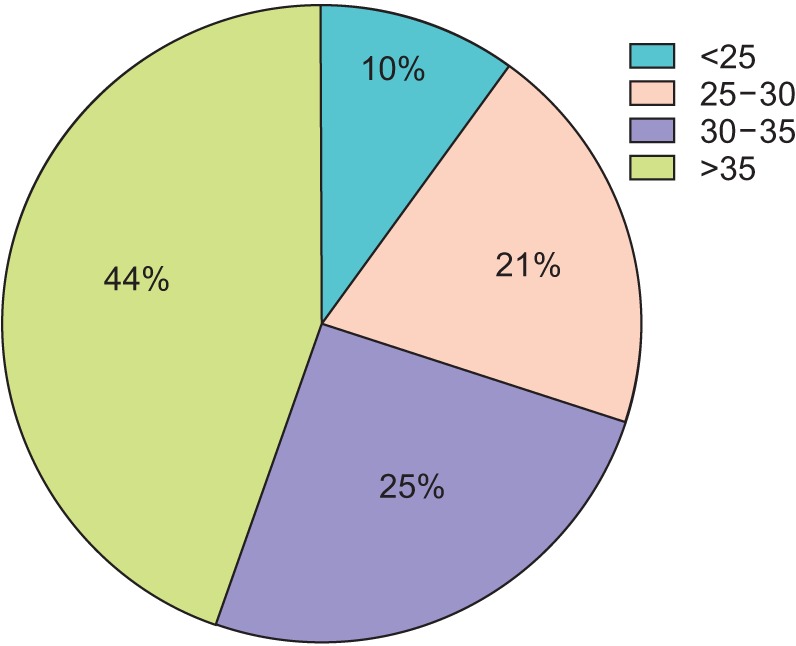

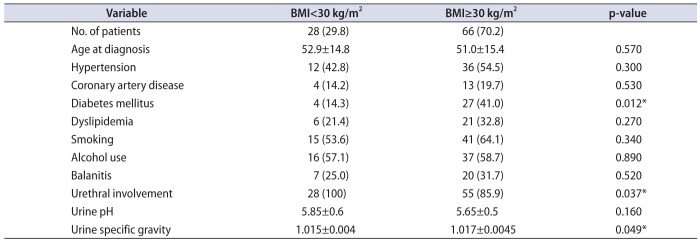

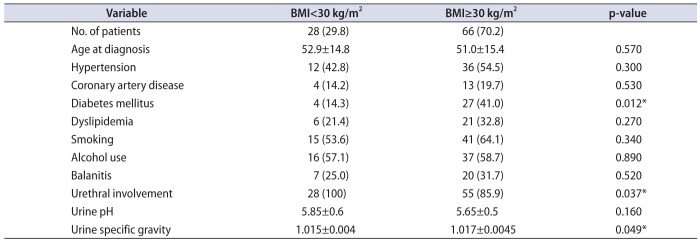

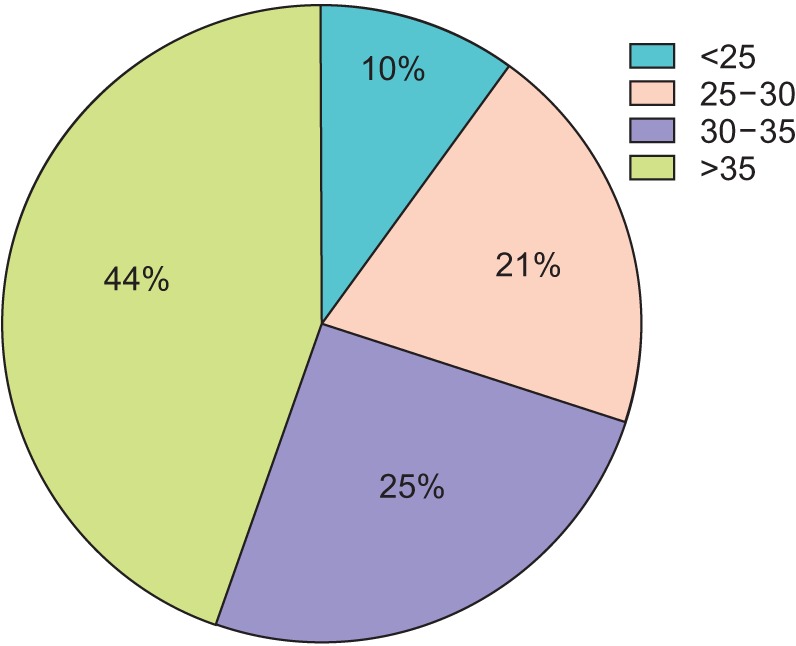

The distribution of BMI in this cohort is displayed in

Fig. 1. Notably, 69.5% of the cohort had a BMI over 30 kg/m

2, while less than 10% had a BMI below 25 kg/m

2. Patients in the BMI>30 kg/m

2 cohort were significantly more likely to have diabetes (41.0% vs. 14.3%, p=0.012), but did not have significantly different rates of hypertension, CAD, or dyslipidemia (

Table 2). All 28 patients with BMI less than 30 kg/m

2 had urethral stricture disease while in patients with BMI 30 kg/m

2 and above, strictures were present in 85.9% (p=0.037). Buried penis was seen in 23.4% of patient in the group of patients in the higher BMI group. Rates of balanitis did not appreciably differ between the group of patients with a BMI<30 kg/m

2 and the group with BMI≥30 kg/m

2. While average urine pH did not differ by BMI, specific gravity was slightly higher in those patients with BMI greater than or equal to 30 kg/m

2. Univariate regression using BMI as a continuous predictor revealed that a one unit increase in BMI significantly increased the odds of balanitis (odds ratio [OR], 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.13; p=0.013), while increasing BMI alone was a protective but non-significant predictor of urethral stricture (OR, 0.96; 95% CI 0.90–1.04; p=0.324).

| Fig. 1Distribution of body mass index in male Lichen sclerosus patients.

|

Table 2

Distribution of patient characteristics stratified by BMI (n=94)

|

Variable |

BMI<30 kg/m2

|

BMI≥30 kg/m2

|

p-value |

|

No. of patients |

28 (29.8) |

66 (70.2) |

|

|

Age at diagnosis |

52.9±14.8 |

51.0±15.4 |

0.570 |

|

Hypertension |

12 (42.8) |

36 (54.5) |

0.300 |

|

Coronary artery disease |

4 (14.2) |

13 (19.7) |

0.530 |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

4 (14.3) |

27 (41.0) |

0.012*

|

|

Dyslipidemia |

6 (21.4) |

21 (32.8) |

0.270 |

|

Smoking |

15 (53.6) |

41 (64.1) |

0.340 |

|

Alcohol use |

16 (57.1) |

37 (58.7) |

0.890 |

|

Balanitis |

7 (25.0) |

20 (31.7) |

0.520 |

|

Urethral involvement |

28 (100) |

55 (85.9) |

0.037*

|

|

Urine pH |

5.85±0.6 |

5.65±0.5 |

0.160 |

|

Urine specific gravity |

1.015±0.004 |

1.017±0.0045 |

0.049*

|

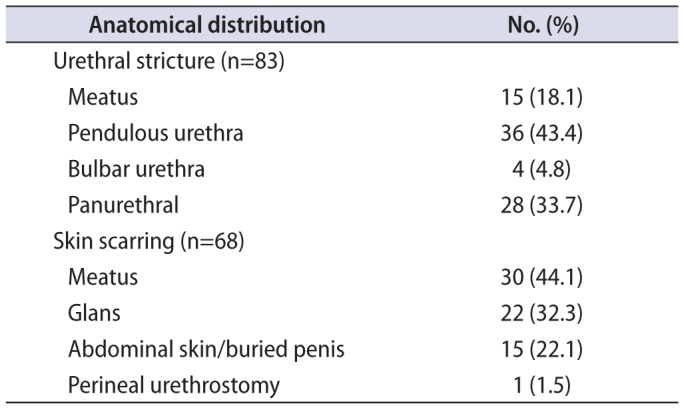

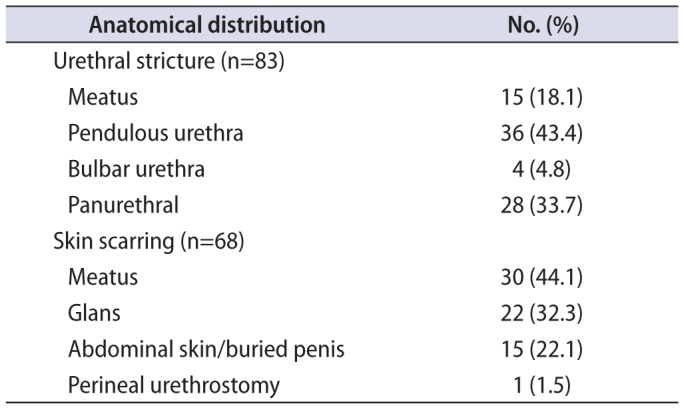

The anatomical distribution of strictures and skin scarring can be seen in

Table 3. Patients with stricture disease were younger than those without (50.1 years vs. 65.7 years, p=0.003) and less likely to suffer from hypertension (47% vs 89%, p=0.031). Comorbid disease burden was otherwise not significantly different between patients with and without strictures. Patients with urethral stricture were less likely to suffer from balanitis than those without stricture (p=0.012).

Table 3

Anatomical distribution of urethral strictures and skin involvement

|

Anatomical distribution |

No. (%) |

|

Urethral stricture (n=83) |

|

|

Meatus |

15 (18.1) |

|

Pendulous urethra |

36 (43.4) |

|

Bulbar urethra |

4 (4.8) |

|

Panurethral |

28 (33.7) |

|

Skin scarring (n=68) |

|

|

Meatus |

30 (44.1) |

|

Glans |

22 (32.3) |

|

Abdominal skin/buried penis |

15 (22.1) |

|

Perineal urethrostomy |

1 (1.5) |

Within this cohort the rate of pathologic diagnosis was approximately 30%. Patients with biopsy-confirmed LS were older (58.9 vs. 48.4, p=0.002), less likely to have urethral stricture (75% vs. 97%, p=0.001), and more likely to have balanitis (46% vs. 23%, p=0.024). Further, the rate of pathologic diagnosis of LS was significantly higher among patients with penile cancer (26% vs. 71%, p=0.023). Rates of biopsy confirmation did not differ based on other comorbidity characteristics.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the cohort of men with LS is diverse and spans a wide range of disease manifestations. While some patients may present with only isolated inflammation near the glans, others suffer from recurrent panurethral strictures and extensive skin scarring. As hypothesized, our results suggest that there may be subsets of patients with different disease subtypes. The younger, healthier patients in our cohort without exception suffered from stricture disease, whereas those patients who were older with higher BMI also frequently had urethral involvement but sometimes suffered from isolated skin inflammation or buried penis. This second group of obese and older patients represents the majority of patients in this study. The 61.7% rate of smoking in this cohort is also well above the overall average rate for United States adults. However it is comparable to a prior study that found the rate of lifetime smoking exposure among patients with LS to be 58%, significantly higher than among control patients with non-LS related urethral stricture disease [

12]. The authors of that study hypothesized that this may reflect a contribution of microvascular pathology to LS, which is consistent with the elevated rates of diabetes mellitus (DM) and CAD among LS patients. We did not observe statistically significant differences in smoking rates among various subgroups of patients in this study, suggesting that perhaps smoking modulates overall LS risk and progression rather than particular disease subtype manifestations and patterns.

Urethral stricture disease remains the hallmark of LS diagnosis in young fit men. Conversely, buried/trapped penis and recurrent skin infections are typical of LS in morbidly obese patients. The best approach to management of these patients is often debatable. At our institution, we utilize topical steroids or immune suppressant creams, which can help with symptomatic improvement. Surgically, limited suprapubic panniculectomy with buried penis repair and possible split thickness skin graft is a treatment option for concealed trapped penis in morbidly obese patients. This minimizes the contact of urine with the genital skin and seems to help in controlling the process. These anecdotally improved outcomes may be a reflection of the possible role of urine contact with genital skin in causing chemical irritation and exacerbating the condition in those patients. We have observed that when urinary diversion is performed by a suprapubic tube or perineal urethrostomy the skin in the area of the diversion will show similar manifestations of scarring. For those patients with strict urethral involvement, substitution urethroplasty with buccal grafting has been the mainstay treatment. We avoid the use of genital skin as a graft source in the setting of LS due to concerns about graft viability and stricture recurrence.

These findings beg the question of whether the two manifestations are truly the same disease. On one hand, a low BMI patient with no evidence of balanitis and genital skin scarring may have extensive urethral involvement and carry the diagnosis of LS, often without pathologic confirmation. On the other hand, a different, morbidly obese patient with a patent urethra but a concealed penis and skin scarring, likely related to recurrent fungal infections due to buried penis, may carry an identical diagnosis. The association with obesity may or may not be genuine, and an additional layer of complexity is added by the clear association of LS with obesity affiliated microvascular diseases such as DM as described above. Even in the setting of pathologic confirmation, there is very little concordance between pathologists in regards to exact diagnostic criteria. LS is generally diagnosed based on a constellation of pathologic findings, but these findings may be subtle or absent and the lack of specific stains for LS means that in some cases clinicopathologic confirmation is necessary [

17].

This work also highlights the relatively low rate of pathologic confirmation of LS in men carrying the clinical diagnosis. The low rate of pathologic confirmation of the clinical diagnosis is alarming even at a tertiary care institution. Notably the rate of biopsy-confirmed disease was significantly higher among men with penile cancer, reflective possibly of more severe disease prompting biopsy or alternatively biopsies eventually performed primarily for workup of penile cancer, with LS as a more coincident finding. It appears that using only the clinical presentation of urethral structuring and/or skin changes may be inadequate to satisfactorily characterize patients as having LS; while there are established microscopic criteria to identify LS on biopsy, there are not clear corresponding clinical criteria to guide non-microscopic diagnosis likely leading to overdiagnosis. In particular, high BMI patients suffering from skin changes secondary to concealed penis may be diagnosed with LS but may be suffering from skin changes mediated by ongoing urine contact as opposed to LS. Misdiagnosis in these patients may lead to suboptimal treatment patterns as well as additional psychological burdens.

Further studies are needed to determine the concurrence rate of clinical diagnosis and pathologic diagnosis to determine if a clinical diagnosis is sufficient. A more precise knowledge of which patients truly suffer from LS will inform more correct prognostic estimates as well as treatment and surgical planning. Based on the results from this study, it may point to a direction of identifying clinical variants of LS that may help guide clinical decisions and expectation management with our patients. The current body of knowledge on which clinicians are able to draw when advising their patients with LS is woefully inadequate.

Several important limitations of this study were identified. Our cohort of patients is relatively small, but LS is a rare condition and this dataset containing 94 patients is a robust sample in the setting of the existing literature. This study did not include a control arm and so incidence of comorbidities and stricture disease could not be compared. Lastly, this is a retrospective single institution study, which may lead to sampling bias. However, these data are collected over a decade from a large, tertiary care urology department and are likely to represent adequately the true population of patients with clinically significant LS.

Go to :

CONCLUSIONS

In sum, these data show that LS in men is a heterogeneous disease with a wide range of skin and urethral manifestations. It affects predominantly older, overweight men but the patient population is diverse and has a range of comorbid disease. Many of these patients with LS lack a true pathologic basis for the diagnosis, which brings into question the diagnostic criteria for LS. Future work should focus on maximizing pathologic confirmation of disease and the development of an accurate classification system incorporating both the urethral and skin expressions of LS. These advances will allow for better patient education as well as more appropriate clinical decision-making.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the University of Michigan Health System's Honest Broker Office for access to the data necessary to complete this work and Heather Crossley for assistance with database management.

Go to :

Notes

Go to :

References

1. Tausch TJ, Peterson AC. Early aggressive treatment of lichen sclerosus may prevent disease progression. J Urol. 2012; 187:2101–2105. PMID:

22503028.

2. Liu JS, Walker K, Stein D, Prabhu S, Hofer MD, Han J, et al. Lichen sclerosus and isolated bulbar urethral stricture disease. J Urol. 2014; 192:775–779. PMID:

24657836.

3. Farrar CW, Dowling P, Mendelsohn SD. Peristomal lichen sclerosus developing posturostomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003; 28:223–224. PMID:

12653720.

4. Bjekic M, Sipetic S, Marinkovic J. Risk factors for genital lichen sclerosus in men. Br J Dermatol. 2011; 164:325–329. PMID:

20973765.

5. Nelson DM, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: epidemiological distribution in an equal access health care system. J Urol. 2011; 185:522–525. PMID:

21168879.

6. Becker K, Meissner V, Farwick W, Bauer R, Gaiser MR. Lichen sclerosus and atopy in boys: coincidence or correlation? Br J Dermatol. 2013; 168:362–366. PMID:

22860989.

7. Lester EB, Swick BL. Eosinophils in biopsy specimens of lichen sclerosus: a not uncommon finding. J Cutan Pathol. 2015; 42:16–21. PMID:

25404144.

8. Gambichler T, Belz D, Terras S, Kreuter A. Humoral and cellmediated autoimmunity in lichen sclerosus. Br J Dermatol. 2013; 169:183–184. PMID:

23301780.

9. Guerrero-Setas D, Perez-Janices N, Ojer A, Blanco-Fernandez L, Guarch-Troyas C, Guarch R. Differential gene hypermethylation in genital lichen sclerosus and cancer: a comparative study. Histopathology. 2013; 63:659–669. PMID:

23998425.

10. Pilatz A, Altinkilic B, Schormann E, Maegel L, Izykowski N, Becker J, et al. Congenital phimosis in patients with and without lichen sclerosus: distinct expression patterns of tissue remodeling associated genes. J Urol. 2013; 189:268–274. PMID:

23174236.

11. Philippou P, Shabbir M, Ralph DJ, Malone P, Nigam R, Freeman A, et al. Genital lichen sclerosus/balanitis xerotica obliterans in men with penile carcinoma: a critical analysis. BJU Int. 2013; 111:970–976. PMID:

23356463.

12. Hofer MD, Meeks JJ, Mehdiratta N, Granieri MA, Cashy J, Gonzalez CM. Lichen sclerosus in men is associated with elevated body mass index, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease and smoking. World J Urol. 2014; 32:105–108. PMID:

23633127.

13. Stewart L, McCammon K, Metro M, Virasoro R. SIU/ICUD Consultation on Urethral Strictures: Anterior urethra-lichen sclerosus. Urology. 2014; 83(3 Suppl):S27–S30. PMID:

24268357.

14. Hartley A, Ramanathan C, Siddiqui H. The surgical treatment of Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011; 44:91–97. PMID:

21713168.

15. Xu YM, Feng C, Sa YL, Fu Q, Zhang J, Xie H. Outcome of 1-stage urethroplasty using oral mucosal grafts for the treatment of urethral strictures associated with genital lichen sclerosus. Urology. 2014; 83:232–236. PMID:

24200196.

16. Liu JS, Han J, Said M, Hofer MD, Fuchs A, Ballek N, et al. Long-term outcomes of urethroplasty with abdominal wall skin grafts. Urology. 2015; 85:258–262. PMID:

25530396.

17. Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013; 14:27–47. PMID:

23329078.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download