Abstract

A freely mobile calcified or noncalcified nodule in the pleural cavity, known as thoracolithiasis, is quite rare. There are several reports of CT findings of thoracolithiasis, but there is no report of thoracolithiasis mistakenly considered as a pleural plaque in a patient with a history of asbestos exposure. We report a case of a 61-year-old man with a mobile pleural stone thoracoscopically confirmed as thoracolithiasis and which was regarded as a pleural plaque on CT scan in a patient with a history of asbestos exposure.

Thoracolithiasis, which is known as a ‘pleural stone’ or an ‘intrapleural loose body’ is a very rare benign condition (1). Thoracolithiasis is defined as a condition in which one or more free bodies with or without calcification are freely mobile in the pleural cavity, without any history of previous trauma, iatrogenic intervention or pleurisy (2). There are several reports of CT findings of thoracolithiasis, but there is no report of thoracolithiasis mistakenly considered as a pleural plaque in an as-bestos-exposed individual with pleural plaques.

Therefore, we report a mobile pleural stone that was thoracoscopically confirmed as thoracolithiasis and was regarded as a pleural plaque in an asbestos-exposed individual with pleural plaques.

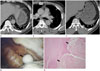

A 61-year-old man visited our hospital with a chief complaint of fever. He had an occupational history of being an insulation worker for 30 years. He had no known history of pleurisy or thoracic intervention. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed patchy air-space consolidation in the left lower lobe which was consistent with pneumonia. Also, there was a 13-mm sized non-calcified, well-defined, ovoid nodule in the left hemithorax which was considered as a pleural plaque (Fig. 1A). Multiple calcified and non-calcified pleural plaques were also identified in both hemithoraces (Fig. 1B). Eight years later, he underwent a follow-up chest CT scan for evaluation of sputum production. On the follow-up CT scan, the previously noted, non-calcified pleural nodule in the left hemithorax revealed a change in location and migration to the lateral portion. There was newly developed calcification within the nodule (Fig. 1C). CT diagnoses included thoracolithiasis and a pedunculated benign fibrous tumor of the pleura. The patient underwent video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) due to the possibility of a pleural tumor. A 2 × 1.5 cm-sized hard, ovoid whitish mass was found floating freely in the pleural cavity (Fig. 1D). Pleural plaques were also seen on the parietal pleura. Histopathologically, the mobile mass showed dense collagenous fibrosis and calcification with lobular necrotic fat cells (Fig. 1E). The final diagnosis was fat necrosis in the pleural cavity and it was consistent with thoracolithiasis.

Thoracolithiasis is a rare benign condition. The exact etiology of thoracolithiasis is unknown. Some explanations have been proposed based on pathologic findings, which include pericardial fat necrosis, pericardial or pleural fat tearing off in the pleural cavity, old tuberculous foci, or an aggregation of macrophages phagocytizing dust, which becomes round and polished after a long period (234). Fat necrosis is more prevalent on the left side, which contains more pericardial fat than the right side (3).

Thoracolithiasis is rarely symptomatic and there are no age or sex predilections (5). Most of the cases were incidentally found on imaging studies or at autopsy. The mass usually measures 5–15 mm in diameter and it may or may not be calcified (1). Approximately half of the reported cases of thoracolithiasis contain areas of calcification, and the calcification revealed spotty, central, peripheral and diffuse patterns (1). However, diffuse calcification of the nodule does not always mean that the nodule has no fat component. Tanaka et al. (6) showed a high-density area in the center of diffuse calcified pleural nodules on both T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance images, which is suggestive of a fat tissue.

Mobility on sequential imaging is the most characteristic finding of thoracolithiasis. Kinoshita et al. (1) demonstrated inferior migration of 11 calcified thoracolithiasis lesions, presumably due to gravity effect. Almost all stones in the study present-ed as ovoid and smoothly marginated nodules freely moving in the pleural cavity. Our case also showed migration of a pleural stone to the dependent portion of the lower hemithorax on se-quential CT scans. One of the differential diagnoses included a pedunculated benign fibrous tumor of the pleura. Pre- and post-contrast enhanced CT may play important roles in the differential diagnosis, because absence of contrast enhancement within the pleural nodule raises the possibility of a non-neoplastic disease (5). Some thoracolithiasis lesions have been reported to enlarge at follow-up studies (27), and it may be difficult to distinguish them from neoplastic disease. However, in the absence of other evidence for neoplastic disease, it is recommended that these mobile calcified nodules do not need to be removed (1). However, a nodule with no or little calcification might be misdiagnosed as a benign neoplasm and may be resected with unnecessary surgery (5).

In our patient with an occupational history of asbestos exposure, there were multiple bilateral pleural plaques on CT scan. These pleural plaques are the most common manifestation and the most characteristic radiographic feature of asbestos exposure. They present as focal and discrete pleural thickening, and they are predominantly located on the posterolateral pleural and diaphragmatic surfaces, typically sparing the apices and costophrenic sulci. Calcification is seen in approximately 15% of patients with asbestos-related pleural plaques (8), and these pleural plaques cause discrete non-mobile thickening of the parietal pleura. On histology, the pleural plaques are relatively acellular, with a “basket-weave” appearance of collagen bundles (9). Because our patient had multiple flat bilateral pleural plaques, thoracolithiasis was initially regarded as one of the nodular pleural plaques, and migration on the follow-up CT scan could be a helpful radiologic finding for the diagnosis of thoracolithiasis.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of thoracolithiasis mimicking a pleural plaque in a patient with an occupational history of asbestos exposure. Thoracolithiasis can be considered in a patient with a non-calcified or calcified pleural nodule revealing mobility on sequential imaging studies and it can also be observed in a patient with multiple asbestos-related pleural plaques.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Thoracolithiasis Mimicking a Pleural Plaque in a 61-year-old man with a History of Asbestos Exposure.

A. Contrast-enhanced chest CT scan obtained at the level of the lung base shows a 13-mm sized non-calcified well-defined ovoid nodule (arrow) in the medial portion of the left lower hemithorax. Multiple non-calcified pleural plaques are also noted on the left posterior costal and diaphragmatic pleura (arrowheads).

B. Chest CT scan obtained below the level of the carina shows discrete calcified and non-calcified pleural plaques (arrowheads) in the left hemithorax.

C. On follow-up evaluation performed eight years later, non-enhanced chest CT shows lateral migration of a pleural nodule (arrow) in the left lower hemithorax and there is newly developed peripheral calcification within the nodule. Pleural plaques are seen again on the left diaphragmatic pleura (arrowheads).

D. In the surgical field, a 2 × 1.5 cm sized whitish ovoid hard mass is found floating freely in the pleural cavity (arrow). Whitish pleural plaques are also seen on the parietal pleura (arrowheads).

E. Histologic evaluation reveals fatty necrotic tissue (arrows) surrounded by hyalinized fibrous tissue (hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification, × 40).

References

1. Kinoshita F, Saida Y, Okajima Y, Honda S, Sato T, Hayashibe A, et al. Thoracolithiasis: 11 cases with a calcified intrapleural loose body. J Thorac Imaging. 2010; 25:64–67.

2. Kosaka S, Kondo N, Sakaguchi H, Kitano T, Harada T, Nakayama K. Thoracolithiasis. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000; 48:318–321.

3. Pineda V, Cáceres J, Andreu J, Vilar J, Domingo ML. Epipericardial fat necrosis: radiologic diagnosis and follow-up. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 185:1234–1236.

4. Iwasaki T, Nakagawa K, Katsura H, Ohse N, Nagano T, Kawahara K. Surgically removed thoracolithiasis: report of two cases. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006; 12:279–282.

5. Kim Y, Shim SS, Chun EM, Won TH, Park S. A pleural loose body mimicking a pleural tumor: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2015; 16:1163–1165.

6. Tanaka D, Niwatsukino H, Fujiyoshi F, Nakajo M. Thoracolithiasis--a mobile calcified nodule in the intrathoracic space: radiographic, CT, and MRI findings. Radiat Med. 2002; 20:131–133.

7. Dias AR, Zerbini EJ, Curi N. Pleural stone. A case report. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1968; 56:120–112.

8. Kim JS, Lynch DA. Imaging of nonmalignant occupational lung disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2002; 17:238–260.

9. Peacock C, Copley SJ, Hansell DM. Asbestos-related benign pleural disease. Clin Radiol. 2000; 55:422–432.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download