Abstract

Ectopic prostatic tissue (EPT) outside the male genitourinary tract is an unusual finding, and it is very rarely found in the rectum or around the peri-rectal region. In addition, the radiologic features of EPT are seldom reported. Also, it is difficult to differentiate EPT found in the rectal subepithelium from the other types of subepithelial tumors. We present here a unique case of EPT found in the retrorectal region, along with the radiologic findings of transrectal ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging with their pathologic correlations.

Ectopic prostatic tissue (EPT) is a very rare finding and it is usually reported in the lower urinary tract, specifically in the bladder and/or the urethra in males. Its histological and immunohistochemical characteristics are not distinguishable from the normal prostate tissue (1). To date, less than five cases of rectal, anal, or perirectal EPT have been reported (234). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no single published report describing the radiographic findings of perirectal EPT.

When EPT is found in the subepithelial layer of the rectum, the radiologic findings are similar to those of the other types of subepithelial tumors; making the diagnosis very difficult. Herein, we report ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of EPT in a 46-year-old man.

A 46-year-old man visited our hospital for a detailed examination of a 25 mm mass located immediately above the anal verge. This mass was coincidentally found on colonoscopy during a routine health check-up. The patient had no rectal symptoms and he had a history of recent antibiotic use for femoral abscess 2 weeks ago.

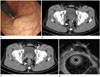

Repeat colonoscopy performed at our hospital revealed a round, sessile polypoid mass with smooth margins measuring about 25 mm in diameter, covered with normal rectal mucosa, and located approximately 5 cm above the anal verge (Fig. 1A). On abdominal-pelvic CT, a mass extending into the presacral space was observed in the posterior perirectal area, and overlying mucosal enhancement was preserved (Fig. 1B, C). Precontrast CT revealed a high-density nodular lesion directed toward the rectal lumen; postcontrast CT showed that the area was not enhanced.

The location of the lesion was confirmed with endoscopic ultrasound to be in the 4th layer (muscularis propria) of the rectum and the perirectal space. The mass was poorly marginated and it partially comprised a septated cystic area (Fig. 1D).

Preoperative MRI revealed a complex cystic and solid mass located across the posterior rectal wall and the presacral space. The location of the cystic portion was consistent with the high-density nodular lesion found on precontrast CT, and it showed high signal intensity on the T1-weighted image (T1WI) and dark signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (T2WI) without enhancement. The solid portion had low signal intensity on T1WI and high signal intensity on T2WI with heterogeneous enhancement (Fig. 2A-C). On the diffusion-weighted image with a b-value of 800, diffusion restriction was not observed in the solid portion of the mass (Fig. 2D).

Based on these radiographic findings, the possibility of an intramural mesenchymal tumor such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) or intramural abscess formation in the rectum was suggested.

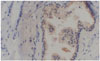

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy results showed benign epithelial cells and tumor or inflammatory cells were not found. Kraske's posterior approach was used for resection of the rectal wall tumor. The mass was multicystic without clear boundaries, located adjacent to muscle layers and muscle fascia. The cyst was filled with clear gel or yellowish-brown mucinous material. Histopathologic examination showed multiple prostatic glands surrounded by fibromuscular stroma. Immunohistochemical staining of glandular epithelial cells was positive for prostate-specific antigen (Fig. 3). The final diagnosis was EPT in the rectal wall.

EPT is a rare diagnosis. It is typically found in the lower urinary tract in males, and EPT outside the urinary tract is even rarer (125).

Two hypotheses have been formulated in regard to the occurrence of EPT in the perirectal area. At around 5 weeks' gestation, the endodermal cloaca divides and differentiates into the rectum and bladder, and the cells capable of differentiating into prostatic tissue might enter the rectal area and form subepithelial EPT (12). Another hypothesis is that the cells available for differentiating into prostatic tissue are present within the rectal subepithelium and form aberrant tubular outgrowths, which develop into EPT (2). However, no single hypothesis has been confirmed.

EPT found outside the urinary tract can be mistaken for malignancy of the gastrointestinal tract and retrovesical space. Although EPT is not among the most frequent differential diagnoses at first, subepithelial lesions in the rectum must be carefully examined in order to distinguish whether it is a malignancy or a benign tumor (6). Thus, transrectal ultrasonography, CT, and MRI are necessary. MRI has been reported to be the optimal modality for evaluating soft tissues (6).

Multiple radiographic differential diagnoses should be considered for a retrorectal mass consisting of complex cystic and solid components. For instance, GIST with internal necrosis may show fluid signal intensity on MRI similar to EPT (6). In addition, mucinous adenocarcinoma can show a fluid signal intensity corresponding to the mucin content, but it has a lace-like peripheral enhancement pattern unlike EPT (7). Retrorectal developmental cysts should also be considered. Of these conditions, an epidermal cyst and a dermoid cyst appear as thin-walled unilocular, round and well-circumscribed lesions. Moreover, a tailgut cyst usually presents adhering to the sacrum or rectum and has a multilocular shape, and as the internal protein concentration increases, the signal intensity will increase on T1WI and decrease on T2WI (67). In premenopausal women with endometriosis, usually affecting the anterior wall of the rectum, it shows hyperintensity on both T1WI and T2WI and obliterates the normal hyperintense fat plane between the uterus and the rectum on T2WI (67). With a recent history of infection, retrorectal abscess formation is possible. However, unlike EPT, the abscess cavities typically show a hypointense center with rim enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1WI (7).

Embryologically, the central zone of the prostate is of mesodermal origin, whereas the peripheral and transition zones are of endodermal origin. Halat et al. (1) reported that the pathologic findings of 80% of EPTs in the urogenital tract of 20 patients were similar to those of the central zone of the prostate. In the present case, the solid portion of EPT showed low signal intensity on T1WI and high signal intensity on T2WI with heterogeneous enhancement; it was similar to the peripheral zone of the prostate on MRI. Moreover, the shape and distribution of the stroma and glands were similar to those of the peripheral zone of the prostate on pathologic evaluation. All these findings suggest that the solid portion of the mass might have been of endodermal origin. Additionally, areas of high signal intensity on T1WI and dark signal intensity on T2WI without enhancement, seem to correspond to the cystic portions of the mass, found on resection. We speculate that these cystic portions may have been formed by the prostate glands.

It is very difficult to diagnose EPT outside the urinary tract before surgery; in most cases, the diagnosis is confirmed postoperatively via histological identification of prostatic acini and stromal structures (3). Surgical resection is recommended for EPT (4) because the possibility of malignant transformation has been reported (48910).

In conclusion, although EPT is a very rare disease, if a mass showing radiographic features similar to those of the normal pro-state is found in the rectal subepithelium, the possibility of EPT needs to be considered.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A 46-year-old man with subepithelial ectopic prostatic tissue in the rectum.

A. Colonoscopic image shows an approximately 25 mm sized, round, sessile polypoid mass with smooth margins, covered with normal rectal mucosa (arrow).

B, C. An axial precontrast CT scan (B) shows an ill-defined posterior perirectal mass (arrowhead) with a focal nodular high density toward the rectal lumen (arrow) on the anterior side of the mass, and an axial contrast enhanced CT scan during the portal phase (C) shows heterogeneous enhancement of the mass (arrowhead).

D. Endoscopic ultrasound shows a poorly-marginated hypoechoic mass (arrowhead) with a partial septated cystic area (arrow) in the 4th layer (muscularis propria) of the rectum and perirectal space.

CT = computed tomography

Fig. 2

MRI findings of subepithelial ectopic prostatic tissue in the rectum.

A, B. Axial T1WI (A) and axial T2WI (B) show a mass extending across the posterior rectal wall and the presacral space with a complex cystic and solid nature. The cystic portion of the mass (arrows) shows high signal intensity on a T1WI and dark signal intensity on a T2WI. The solid portion (arrowhead) shows low signal intensity on a T1WI and high signal intensity on a T2WI.

C. Subtraction image shows no enhancement in the cystic portion of the mass and heterogeneous enhancement in the solid portion of the mass (arrowhead).

D. On the diffusion-weighted image with a b-value of 800, diffusion restriction was not observed in the solid portion of the mass (arrowhead).

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, T1WI = T1-weighted image, T2WI = T2-weighted image

References

1. Halat S, Eble JN, Grignon DJ, Lacy S, Montironi R, MacLennan GT, et al. Ectopic prostatic tissue: histogenesis and histopathological characteristics. Histopathology. 2011; 58:750–758.

2. Fulton RS, Rouse RV, Ranheim EA. Ectopic prostate: case report of a presacral mass presenting with obstructive symptoms. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001; 125:286–288.

3. Dai S, Huang X, Mao W. A novel submucosa nodule of the rectum: a case of the ectopic prostatic tissue outside the urinary tract. Pak J Med Sci. 2013; 29:1453–1455.

4. Gardner JM, Khurana H, Leach FS, Ayala AG, Zhai J, Ro JY. Adenocarcinoma in ectopic prostatic tissue at dome of bladder: a case report of a patient with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010; 134:1271–1275.

5. VanBeek CA, Peters CA, Vargas SO. Ectopic prostate tissue within the processus vaginalis: insights into prostate embryogenesis. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005; 8:379–385.

6. Kim H, Kim JH, Lim JS, Choi JY, Chung YE, Park MS, et al. MRI findings of rectal submucosal tumors. Korean J Radiol. 2011; 12:487–498.

7. Purysko AS, Coppa CP, Kalady MF, Pai RK, Leão Filho HM, Thupili CR, et al. Benign and malignant tumors of the rectum and perirectal region. Abdom Imaging. 2014; 39:824–852.

8. Adams JR Jr. Adenocarcinoma in ectopic prostatic tissue. J Urol. 1993; 150:1253–1254.

9. Somwaru AS, Alex D, Zaheer AK. Prostate cancer arising in ectopic prostatic tissue within the left seminal vesicle: a rare case diagnosed with multi-parametric magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance imaging-transrectal ultrasound fusion biopsy. BMC Med Imaging. 2016; 16:16.

10. Tan FQ, Xu X, Shen BH, Qin J, Sun K, You Q, et al. An unusual case of retrovesical ectopic prostate tissue accompanied by primary prostate cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2012; 10:186.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download