Abstract

Multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (MMPH) is a relatively rare pulmonary disorder that can be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). It has been rarely reported in children or adolescents. MMPH is a hamartomatous process of the lung with multiple small nodules, composed of type II pneumocytes. Plain radiography and chest CT in MMPH may demonstrate numerous small nodules measuring 1–10 mm in diameters, distributed randomly throughout both lungs. If MMPH is an initial presentation of TSC, and unless we are familiar with this lung manifestation of TSC, radiologic findings can mimic miliary tuberculosis or metastatic disease. We report a teenage girl with TSC and histologically confirmed MMPH which mimicked miliary tuberculosis at the initial presentation.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a hereditary neurocutaneous syndrome with a classic triad of seizures, mental retardation, and adenoma sebaceum. It is inherited by an autosomal dominant pattern and is caused by a mutation in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes encoding hamartin and tuberin respectively, both of which are thought to act as tumor suppressor genes (1). Lack of functional hamartin or tuberin may explain the development of hamartomas and various tumors in TSC. Almost all systems or organs of the body can be involved in TSC. Clinical manifestations are unique in many cases but in some cases, characteristic findings from imaging are the first step to raise a possibility of TSC.

Hamartomas in TSC patients are most commonly found in the skin, kidneys, brain, and heart. Less frequently, they can involve the retina, gingiva, bones, gastrointestinal tract, and lungs. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a well known and major feature of the pulmonary manifestation of TSC. Pulmonary manifestations are known to occur in approximately 1–2.3% of TSC patients, but the incidence turned out to be higher based on radiologic findings in up to 26–39% of female TSC patients (2). More recently, multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia (MMPH) has been reported to occur in association with TSC (34). MMPH is a hamartomatous process of the lung with multiple small nodules which are composed of type II pneumocytes. MMPH is not a new entity, but if it is an initial presentation of TSC and we are not familiar with this rare manifestation of TSC, it may lead incorrectly to other diagnoses such as miliary tuberculosis or metastatic lung disease. MMPH in TSC has been rarely reported in children or adolescents (5). Here, we report a teenage girl with MMPH and TSC which mimicked miliary tuberculosis at the initial presentation.

A 15-year-old girl was referred to our institute because of abnormal findings on chest radiographs. An initial chest radiograph for student screening a year ago showed numerous fine nodular opacities, measuring a few millimeters, and evenly scattered throughout both lungs (Fig. 1A). With an initial diagnosis of miliary tuberculosis, anti-tuberculosis medications were given at the local public health center. However, standard anti-tuberculosis treatment for more than 9 months failed to show radiological improvement. Subsequently she was referred to our hospital for further evaluation.

On admission, the patient had no respiratory symptoms. Physical examination revealed wheezing over both lung fields and skin lesions including hypopigmented macules and shagreen patches. She was mentally retarded (Full Scale Intelligence Quotient 55). The laboratory test did not show any abnormal results at the time of her first visit. She had a history of temporary seizure-like events during infancy. About ten months ago, she had multiple events of decreased responsiveness and automatic hand movements. Video-electroencephalography showed a mild cerebral dysfunction but interictal epileptiform discharge was not observed. Antiepileptic medication was not given. She had no family history of tuberous sclerosis.

The high resolution CT (HRCT) showed miliary nodules and multiple small nodules, varying in diameter from 3 to 12 mm, and randomly distributed throughout both lung fields (Fig. 1B). No cysts, pleural effusions, or significant mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy were noted. Bronchoscopy revealed no endobronchial lesions. Brain MRI demonstrated multiple subependymal nodules along the ventricular margins, and tubers in the cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter of both hemispheres (Fig. 2). Subsequent ultrasonography and CT of the abdomen showed small cysts and presumed angiomyolipomas in the both kidneys.

A biopsy was performed on the right upper and middle lobes by means of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Histologically, the parenchymal tissue showed multifocal areas of increased cell density, and consisted of increased septal fibrosis and papillary growths of hyperplastic type II pneumocytes (Fig. 3A). No caseating necrosis or granulomatous inflammation was identifiable. Immunohistochemically, most of the proliferating epithelial cells of the lesion were positive for anti-pan-cytokeratin (Fig. 3B) and anti-thyroid transcription factor-1. However, they were negative for anti-melanocyte marker (HMB-45).

TSC is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the triad of seizures, mental retardation, and multiple hamartoma lesions. Our patient could be diagnosed as having definite TSC since she had all the features of the classic triad and two major features (subependymal nodules and renal angiomyolipoma) of the clinical diagnostic criteria. In our patient, there was no family history of TSC, supporting this case was sporadic, although gene study was not performed.

LAM and MMPH are two major lung manifestations of TSC. LAM is a rare lung disease characterized by diffuse proliferation of abnormal smooth muscle-like cells and cystic destruction of the lung. It is more common in young women who present with dyspnea and pneumothorax (3).

MMPH is another lung manifestation of TSC. The precise prevalence of MMPH in patients with TSC is not known, but may be as high as 40–58% (6). There is no gender restriction, and MMPH may occur in association with LAM in TSC patients (3). In our case, there was no associated feature of LAM on CT. In MMPH, multiple pulmonary nodules composed of benign alveolar type II cells are found throughout the lung. These lesions stain with cytokeratin and surfactant proteins A and B, but not with HMB-45, or hormonal receptors which show strong positivity in LAM (4).

Chest CT in patients with MMPH demonstrates small nodules measuring 1–10 mm in diameter, which are randomly distributed throughout the lung with regard to the secondary lobules (4). The differential diagnosis should include a miliary granulomatous infection, hematogenous metastases, Langerhans' cell histiocytosis (LCH), or atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH). Miliary tuberculosis shows a very fine nodular or reticulonodular pattern with an even distribution on HRCT. A review of HRCT findings in 25 patients who had proven miliary tuberculosis, demonstrated miliary nodules measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter (7). Additional radiological findings, such as intra- and interlobular septal thickening, intrathoracic lymphadenopathy or pleural effusion on HRCT favors miliary tuberculosis. Hematogenous metastases typically appear as small discrete nodules that have a peripheral and basal predominance on CT when limited in number. Metastatic lung disease is much less common in children than in the adult population. In addition, hematogenous metastases and MMPH are quite different in clinical features. In LCH, there are nodules as well as cysts that predominantly involve upper lung zones with relative sparing of the costophrenic angles (8). Relative sparing of the lung bases is a useful feature of LCH to differentiate it from other lung diseases (8). In MMPH, the nodules are randomly distributed and the costophrenic angles can be involved (3). Kushihashi et al. (9) described CT findings of AAH that demonstrated small nodules with ground-glass opacity. Ground-glass opacity in MMPH is correlated with decreased alveolar air spaces due to hyperplastic proliferation of type II pneumocytes and infiltration of macrophages into the alveoli (10). However, multicentric lesions seen in MMPH are not common in AAH.

Clinically, patients with isolated MMPH usually have no respiratory symptoms as seen in our case (10). Some patients with MMPH may present with dyspnea, cough, and mild to moderate hypoxemia. Unlike pulmonary LAM, treatment is usually not necessary because MMPH does not appear to be fatal or progressive. MMPH has not shown any malignant potential although there is a potential loss of tumor suppressor function in TSC gene mutations (10).

The incidence of MMPH seems to be underestimated in children or adolescents because there is usually no respiratory symptom requiring imaging studies, and chest CT is less frequently performed in pediatric patients than in adult patients. However, it is not practical to perform chest CT for screening in all TSC patients.

It is difficult to differentiate MMPH or benign hamartomatous lung disease from other diseases requiring further evaluation or treatment on the basis of radiographic findings only. A definitive diagnosis of MMPH can only be made by a lung biopsy. Most MMPH occurrences are in patients with TSC, and its clinical course is usually benign. Therefore it is important to find the stigmata of TSC and do clinical and radiological follow-ups before undergoing histological confirmation in MMPH patients.

In summary, we report a teenage girl with MMPH and TSC which mimicked miliary tuberculosis at the initial presentation. MMPH is a benign hamartomatous process of the lung with multiple small nodules which are composed of type II pneumocytes. When randomly distributed tiny nodules are observed on chest radiographs or chest CT in patients suspected of TSC, MMPH, a recently recognized entity in TSC, should be considered.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia with tuberous sclerosis complex in a 15-year old girl.

A. Initial chest radiograph for student screening shows numerous fine nodular opacities evenly scattered throughout both lungs.

B. High resolution chest CT shows nodules and multiple, randomly distributed, 3–12 mm nodules. No cysts are seen.

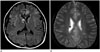

Fig. 2

Brain MR imaging of multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia with tuberous sclerosis complex in a 15-year old girl.

A. Axial FLAIR image shows a subependymal nodule near the right foramen Monro and multiple high signal intensities at the cerebral cortex and subcortical white matter suggesting cortical and subcortical tubers.

B. Axial gradient echo image shows calcified subependymal nodules along the lateral ventricular margins.

FLAIR = fluid attenuated inversion recovery, MR = magnetic resonance

Fig. 3

Microscopic findings of VATS biopsy specimens of multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplaisa with tuberous sclerosis complex in a 15-year old girl.

A. Close-up view of the nodule show increased septal thickness and pneumocyte hyperplasia (arrows) (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100).

B. Immunohistochemically, most of the proliferating epithelial cells of the lesion are positive for pan-cytokeratin (brown color) (pan-cytokeratin stain, × 40).

VATS = video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

References

1. Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, tuberin and hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003; 13:1259–1268.

2. Maruyama H, Ohbayashi C, Hino O, Tsutsumi M, Konishi Y. Pathogenesis of multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia and lymphangioleiomyomatosis in tuberous sclerosis and association with tuberous sclerosis genes TSC1 and TSC2. Pathol Int. 2001; 51:585–594.

3. Franz DN, Brody A, Meyer C, Leonard J, Chuck G, Dabora S, et al. Mutational and radiographic analysis of pulmonary disease consistent with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia in women with tuberous sclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164:661–668.

4. Kobashi Y, Sugiu T, Mouri K, Irei T, Nakata M, Oka M. Clinicopathological analysis of multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia associated with tuberous sclerosis in Japan. Respirology. 2008; 13:1076–1081.

5. Behnes CL, Schütze G, Engelke C, Bremmer F, Gunawan B, Radzun HJ, et al. 13-year-old tuberous sclerosis patient with renal cell carcinoma associated with multiple renal angiomyolipomas developing multifocal micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia. BMC Clin Pathol. 2013; 13:4.

6. Northrup H, Krueger DA. International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 Iinternational Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013; 49:243–254.

7. Hong SH, Im JG, Lee JS, Song JW, Lee HJ, Yeon KM. High resolution CT findings of miliary tuberculosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998; 22:220–224.

8. Webb WR, Muller NL, Naidich DP. High-resolution CT of the lung. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2014. p. 368–381.

9. Kushihashi T, Munechika H, Ri K, Kubota H, Ukisu R, Satoh S, et al. Bronchioloalveolar adenoma of the lung: CT-pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1994; 193:789–793.

10. Fujitaka K, Isobe T, Oguri T, Yamasaki M, Miyazaki M, Kohno N, et al. A case of micronodular pneumocyte hyperplasia diagnosed through lung biopsy using thoracoscopy. Respiration. 2002; 69:277–279.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download