Abstract

Primary hepatic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is an extremely rare lesion. Primary hepatic lymphomas are known to present as a single mass in > 70% of cases, and in many instances with no specific features on imaging. Herein, we described a case of primary hepatic MALT lymphoma in a 71-year-old woman. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a mass, 4.5 × 3.0 cm, in liver segment 2 (S2) that was poorly defined, with subtle enhancement during the arterial phase. Gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging also showed an arterially enhancing mass in S2, with low signal intensity during the hepatobiliary phase and high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging with a high b-value. On fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT imaging, the mass showed a high standardized uptake value. Ultrasonography (US) revealed a hypoechoic mass, and US-guided core needle biopsy confirmed a hepatic MALT lymphoma.

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas are an extranodal subset of marginal zone B-cell lymphomas and represent > 8% of all types of lymphomas (1). In 1983, Isaacson and Wright (2) initially described MALT lymphomas as a distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma arising in the gastrointestinal tract. MALT lymphomas can be found at mucosal sites such as the stomach, lung, and salivary gland or from sites, which share an embryologic origin with mucosa such as the thyroid that normally lacks organized lymphoid tissue (3).

Primary hepatic MALT lymphoma is an extremely rare lesion, with only 45 cases reported in the English literature (45). Because of its rarity, the radiologic findings in patients with this lesion are seldom described, to our best knowledge. Herein, we reported a patient with pathologically proven primary MALT lymphoma who underwent ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with CT (FDG PET/CT).

A 71-year-old woman with early-stage gastric cancer was admitted to our hospital for metastasis work-up. She had a medical history of diabetes mellitus, as well as cervical cancer for which she underwent radical hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy 9 years earlier. On admission, a physical examination showed no abnormal findings. Laboratory tests revealed leukopenia (white blood cell count = 2800/mm3) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count = 109000/mm3) related to cirrhosis. Values on liver function tests were 49 U/L for aspartate aminotransferase and 49 U/L for alanine aminotransferase. The patient was positive for hepatitis B surface antigen, with a titer of 1921.8585 and a signal-to-cutoff ratio of > 50, and hepatitis B virus DNA [7.1 log (10) copies/mL). The serum alpha-fetoprotein level was normal.

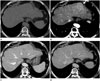

Liver CT (triple-phase CT) revealed a mass, 4.5 × 3.0 cm, in liver segment 2 (S2). The mass was poorly-defined with mild arterial enhancement (Fig. 1B) but not visualized on a the non-enhanced scan (Fig. 1A) in the portal venous (Fig. 1C) or delayed phases (Fig. 1D). Significant regional lymphadenopathy or distant metastases were not detected.

Subsequently, we performed MRI using gadoxetic acid [Gd-EOB-DTPA (Primovist)] (Bayer-Schering, Berlin, Germany). The tumor showed iso-signal intensity on T1-weighted images and homogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 2A). Dynamic study of the tumor showed a homogeneous arterial enhancement and no distortion of vessels traversing the mass (Fig. 2B). The tumor demonstrated iso-signal intensity relative to normal liver parenchyma in the portal and delayed phases. In the hepatobiliary phase, the lesion had low signal intensity (Fig. 2C). On diffusion-weighted imaging, the intensity was high, with a high b-value (800 s/mm2) (Fig. 2D). The mass lesion was devoid of blood products or a fat component.

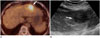

FDG PET/CT imaging revealed a high standardized uptake value (max SUV = 6.59) at the S2, suggesting a markedly hypermetabolic mass (Fig. 3A).

Considering the patient's clinical history and radiologic findings, the differential diagnosis included a malignant hypervascular mass, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), lymphoma, or metastatic hepatic tumors, and a benign hypervascular mass, such as an inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) or a hepatic adenoma. Our initial thought was that malignant hypervascular liver tumors are more likely than benign ones; furthermore, in a patient with cirrhosis, HCC could be suspected because it is the most common type of primary hypervascular liver cancer. Hepatic lymphoma was excluded from the diagnosis based on dynamic CT and MRI evidence of tumor penetration by existing blood vessels in hepatic malignant lymphoma (6).

Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy was conducted to confirm the histopathologic diagnosis. On ultrasound, the mass was hypoechoic, as compared with the liver parenchyma (Fig. 3B). Biopsy results demonstrated markedly intense, diffuse porto-periportal atypical lymphocytic infiltration with lymphoid follicle formation. Immunohistochemical staining showed that the lesion was positive for CD20 and CD79a and negative for CD3, cyclin D1, BCL-6, and CD5, consistent with MALT lymphoma (Fig. 4).

Treatment consisted of radiation therapy alone. At the 1-year follow-up, the primary hepatic MALT lymphoma had completely disappeared on MRI, and there was no significant uptake of FDG in the liver on follow-up FDG PET/CT.

A primary hepatic MALT lymphoma is extremely rare. Jaffe (7) reported that hepatic malignant lymphomas make up < 1% of all malignant lymphomas, and hepatic MALT lymphomas reportedly occur in only 3% cases of hepatic malignant lymphoma.

The etiology of hepatic malignant lymphomas, especially MALT lymphoma, is not elucidated. MALT lymphomas originate at sites normally devoid of organized lymphoid tissue, whereas lymphomas almost always arise in the setting of chronic inflammatory disorders that are characterized by the accumulation of lymphoid tissue (8). A relationship between hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatic malignant lymphoma has been previously reported, however, there are no reports on a relationship between HCV and MALT lymphoma (4).

As is well known, primary hepatic lymphoma presents as a single mass in > 70% of cases, and in many cases MALT lymphomas are solitary masses with diverse findings on radiologic imaging (4). Because the imaging findings are nonspecific, it is difficult to make a definite diagnosis based on imaging without histopathology.

To date, the characteristic diagnostic radiologic findings specific to primary hepatic lymphoma, including MALT lymphoma, are unknown. On CT scans, the hepatic MALT lymphoma is enhanced peripherally in the arterial phase and low attenuated in the delayed phase, according to an earlier report (4). Another study indicated that hepatic MALT lymphoma shows prolonged enhancement in the delayed phase on dynamic CT and is enhanced in the arterial phase with persisting enhancement in the portal phase on dynamic MRI (9). Similarly, in our case, enhancement was evident in the arterial phase; however, unlike previous reports, our case showed iso-attenuation in the delayed phase and undistorted vessels traversing the liver mass (6).

When diagnosing a hypervascular liver tumor, various enhancement patterns and ancillary imaging features such as capsule, hepatobiliary phase imaging, intralesional fat, hemorrhage, and restricted diffusion could be of help in characterizing the liver tumor. Our case showed a poorly defined mass with homogeneous arterial enhancement, but according to a previous report, homogeneous arterial enhancement was not reported as an imaging feature of IPTs of the liver (6). One of the diagnostic features of HCC i.e., portal venous or delayed phase washout was not seen in this case. It is unlikely that our patient had a heterogeneous liver mass due to the presence of hemorrhage, lipid/fat, and rarely calcification, which are common imaging features of hepatic adenoma (5).

In conclusion, despite the difficulty involved, early radiologic diagnosis of primary hepatic MALT lymphoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a hypervascular liver tumor, especially if tumor penetration by existing blood vessels can be visualized.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Hepatic MALT lymphoma in a 71-year-old woman on CT.

On unenhanced (A) and dynamic liver CT, the mass shows a mildly arterial enhancing mass (arrow) in liver segment 2 (B) in the arterial phase and iso-attenuation relative to the liver on unenhanced image (A), in the portal phase (C), and in the delayed phase (D).

CT = computed tomography, MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

Fig. 2

Hepatic MALT lymphoma in a 71-year-old woman on gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI.

A. T2-weighted axial MR image shows a homogeneous high signal instensity mass (arrowhead) in liver segment 2.

B, C. On gadoxetic acid-enhanced arterial phase (B), the mass shows homogeneous enhancement (arrowhead) and undistorted vessels traversing the mass (curved black arrow). The mass shows low signal intensity (arrowhead) in the hepatobiliary phase (C).

D. With diffusion-weighted imaging, the intensity is high (arrowhead), with a high b-value (800 s/mm2).

MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

Fig. 3

Hepatic MALT lymphoma in a 71-year-old woman on FDG PET/CT and US.

A. FDG PET/CT scanning reveals a high standardized uptake value (max SUV = 6.59) (arrow) at liver segment 2, suggesting a hypermetabolic mass.

B. US demonstrates a hypoechoic solid mass (arrow) in liver segment 2.

FDG PET/CT = fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography, MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, US = ultrasonography

Fig. 4

Histopathologic findings and immunohistochemical staining of hepatic MALT lymphoma in a 71-year-old woman.

A. The microscopic finding of the tumor includes a diffuse infiltration of small atypical lymphocytes expanding portal tracts, extending into lobules, and effacing normal hepatocytes (hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 100).

B. Immunohistochemical staining reveals CD20-positive lymphoid cells (× 400).

MALT = mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

References

1. Matasar MJ, Zelenetz AD. Overview of lymphoma diagnosis and management. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008; 46:175–198, vii.

2. Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer. 1983; 52:1410–1416.

3. Park JY, Choi MS, Lim YS, Park JW, Kim SU, Min YW, et al. Clinical features, image findings, and prognosis of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a multicenter experience of 45 cases. Gut Liver. 2014; 8:58–63.

4. Doi H, Horiike N, Hiraoka A, Koizumi Y, Yamamoto Y, Hasebe A, et al. Primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol. 2008; 88:418–423.

5. Grazioli L, Olivetti L, Mazza G, Bondioni MP. MR imaging of hepatocellular adenomas and differential diagnosis dilemma. Int J Hepatol. 2013; 2013:374170.

6. Apicella PL, Mirowitz SA, Weinreb JC. Extension of vessels through hepatic neoplasms: MR and CT findings. Radiology. 1994; 191:135–136.

7. Jaffe ES. Malignant lymphomas: pathology of hepatic involvement. Semin Liver Dis. 1987; 7:257–268.

8. Rodallec M, Guermazi A, Brice P, Attal P, Zagdanski AM, Frija J, et al. Imaging of MALT lymphomas. Eur Radiol. 2002; 12:348–356.

9. Shiozawa K, Watanabe M, Ikehara T, Matsukiyo Y, Kikuchi Y, Kaneko H, et al. A case of contiguous primary hepatic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and hemangioma ultimately diagnosed using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Case Rep Oncol. 2015; 8:50–56.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download