INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a well-known pathogen causing chronic viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). On the other hand, increased incidence of various extrahepatic autoimmune diseases, such as Sjogren's syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, and lymphoma has also been re-ported (1). HCV, being lymphotrophic as well as hepatotrophic, has attracted speculation about a causative role in some cases of lymphoma (2). In particular, several investigators have reported an association between HCV and B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (1234). Chronic antigenic stimulation by HCV has been suspected to be related to the development of clonal B cell expansion (14). Although the mechanism is not fully understood, we present a case of a patient with HCV-related cirrhosis who showed simultaneous intrahepatic development of HCC and extrahepatic involvement by B cell lymphoma.

CASE REPORT

A 38-year-old male with HCV infection and liver cirrhosis presented with right upper quadrant abdominal pain. On physical examination, the abdomen was tender and slightly rigid in the right upper quadrant.

Serum biochemical laboratory data of liver function parameters, such as aspartate aminotransferase (170 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (35 IU/L), total bilirubin (3.88 mg/dL), alkaline phosphatase (186 IU/L), and lactic dehydrogenase (778 IU/L) showed an increase along with mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count 8410/mm3).

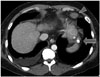

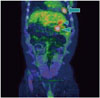

In the abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, an exophytic hypervascular mass was detected in liver segment #2 in the arterial phase (Fig. 1A). The mass showed washout during the portal (Fig. 1B) and delayed phase (Fig. 1C) studies, which strongly suggested HCC. We then performed transarterial chemoembolization. Selective hepatic angiogram revealed tumoral staining in the left lateral segment of the liver. After superselection of the feeding artery with a microcatheter, injection of 8 cc mixture consisting of 50 mg adriamycin and 10 cc lipiodol was administered. Dense uptake of lipiodol in the tumor was noted. Two months later, in the follow-up abdominal CT scan, homogenous lipiodol uptake was noted and a soft tissue mass had developed in the pericardial fat tissue (Fig. 2). In serial positron emission tomography CT (PET CT) scan, increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake was noted in the pericardial fat, and retrosplenic and peripancreatic spaces (Fig. 3). CT-guided biopsy was performed from a pericardial fat soft tissue mass. The specimen acquired via CT-guided biopsy showed large cells with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Immunohistochemical staining showed CD20 positivity and Bcl-2 positivity. Pathological diagnosis of diffuse large B cell lymphoma was confirmed.

After series of chemotherapy treatments, the soft tissue mass in the pericardiac, retrosplenic, and peripancreatic spaces that was diagnosed as lymphoma decreased in size. No FDG uptake was observed in the follow-up PET CT.

DISCUSSION

HCV is a well-known pathogen causing chronic viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and HCC. It has also been implicated in a number of extra-hepatic autoimmune diseases, such as Sjogren's syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, and lymphoma (1). A recent study reported that HCV appears to be involved in the pathogenesis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (56789).

B-cells are activated through engagement of surface immunoglobulin/B-cell antigen receptor complex (BCR). B-cells can also be stimulated via a multi-protein cell surface complex comprising the CD81 receptor, the signal transducer CD19, and the CD21 molecule (567). Co-stimulation of the CD19/CD21/CD81 complex along with the BCR lowers the threshold for B-cell activation and proliferation (8). It has been reported that CD81 can bind to at least two sites on the HCV envelope protein, E2. CD81/E2 interaction does not apparently promote B-cell activation (9). However, B cells with specific anti-HCV surface immunoglobulins can simultaneously interact with viral E2 protein via CD81, resulting in dual activation signals leading to B cell proliferation. Consequently, chronic antigenic stimulation may play a significant role in the development of an initial polyclonal B-cell expansion. It may progress to autonomous B-cell proliferation, immune dysregulation, and eventually B-cell malignancy (1).

The simultaneous incidence of HCC and diffuse large B cell lymphoma in a HCV carrier is very rare. Besides few case reports, the association between HCC and diffuse large B cell lymphoma has not yet been established (10).

In our case, lymphoma arose from the pericardial, retrosplenic, and peripancreatic lymph nodes. Metastasis from HCC to pericardial lymph nodes is unusual, whereas 10% of pericardial lymph nodes are involved in lymphoma patients. Considering the pathology and epidemiology, we should carefully consider the possibility of lymphoma occurrence in HCV-infected patients.

This report presents a rare case of HCC and comorbid diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that developed in a patient with HCV infection and emphasizes a potential causal relationship between hepatitis C and lymphoma, in addition to the well-known risk of HCC development in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download