Abstract

Purpose

To determine relationships between different types of rotator cuff tears and radiographic abnormalities.

Materials and Methods

The shoulder radiographs of 104 patients with an arthroscopically proven rotator cuff tear were compared with similar radiographs of 54 age-matched controls with intact cuffs. Two radiologists independently interpreted all radiographs for; cortical thickening with subcortical sclerosis, subcortical cysts, osteophytes in the humeral greater tuberosity, humeral migration, degenerations of the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints, and subacromial spurs. Statistical analysis was performed to determine relationships between each type of rotator cuff tears and radiographic abnormalities. Inter-observer agreements with respect to radiographic findings were analyzed.

Results

Humeral migration and degenerative change of the greater tuberosity, including sclerosis, subcortical cysts, and osteophytes, were more associated with full-thickness tears (p < 0.01). Subacromial spurs were more common for full-thickness and bursal-sided tears (p < 0.01). No association was found between degeneration of the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joint and the presence of a cuff tear.

Rotator cuff tears are a common cause of shoulder pain. The diagnosis of rotator cuff tears is based upon clinical assessment and radiologic images, including plain radiographic, ultrasound, and MR images. Among these modalities, plain radiography is the most commonly used imaging modality in cases of shoulder pain. However, the usefulness of radiographs for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tear is limited. Radiographic findings of patients with a documented rotator cuff tear include a decreased acromiohumeral distance, a hooked acromion, and degenerative changes of the greater tuberosity and acromioclavicular joint (1, 2, 3, 4), and these findings are generally used to predict the presence of rotator cuff pathology. However, in studies on relationships between radiographic abnormalities and rotator cuff pathology have returned conflicting results (5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet examined the relationship between radiographic findings and subtypes of partial thickness rotator cuff tears classified by location.

Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to assess the relationship between each type of rotator cuff tear and radiographic abnormalities of the greater tuberosity, acromion, acromioclavicular, and glenohumeral joints.

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board, which waived the requirement for patient informed consent.

We reviewed the surgical records of 104 patients (50 men and 54 women; mean age of 59.5 years) with radiographs, diagnosed with a supraspinatus tendon tear from 1st March 2010 to 28th February 2013. At arthroscopy, 64 patients (33 men and 31 women; mean age 62.1 years) were diagnosed with a full thickness tear, and 40 (19 men and 21 women; mean age 55.3 years) were diagnosed with a partial thickness tear. Of the 40 partial thickness tears, 22 were articular-sided and 18 were bursal-sided. The study included a control group of 54 patients (13 men and 41 women; mean age of 52.3 years) with intact rotator cuffs. In the control group, 10 patients were diagnosed by arthroscopy and 44 by MR arthrography. Arthroscopic diagnoses in the control group were; 7 patients with superior labral tear from anterior to posterior (SLAP) lesion, 2 with adhesive capsulitis, and 1 with acromioclavicular arthritis. Image based diagnoses in the control group were; 29 patients without any pathologic finding, 14 with a SLAP lesion, and 1 with adhesive capsulitis. In this study, we focused on whether a rotator cuff tear was present or not. Tear sizes and degree of tendon retraction were not considered.

Four radiographs were taken of each shoulder (True shoulder anterior-posterior (AP) projection, supraspinatus outlet view, axillary lateral view, and caudal 30-degree tilt view).

MR arthrography was performed on 1.5-T or 3.0-T units (Achieva, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) using our standard shoulder protocol; axial and oblique coronal T1 spectral presaturation with inversion recovery (SPIR) with fat suppression [repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 500/10 msec], fat suppressed T1 abduction external rotation view (TR/TE = 500/10 msec), oblique sagittal T1-weighted spin echo (TR/TE = 580/10 msec), oblique coronal and sagittal T2-weighted image without fat suppression (TR/TE = 2400/80 msec), and oblique coronal T2 SPIR with fat suppression (TR/TE = 3200/70 msec). All sequences were obtained using a section thickness of 3 mm and a field of view of 12 cm. For MR arthrography, a 20-22 gauge spinal needle was inserted through the medial border of the humeral head under fluoroscopic guidance and placed into the glenohumeral joint. All patients had received 12 mL of intra-articular contrast mixture via an anterior approach. The contrast mixture was obtained by combining 0.1 mL of gadobutrol (Gadovist, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany), 3 mL of iopromide (Ultravist 300, Bayer Health Care, Leverkusen, Germany), 2 mL of 2% lidocaine and 10 mL of saline.

As has been done previously (9), radiographic abnormalities were classified into seven categories: abnormalities of the greater tuberosity including; 1) cortical thickening with subcortical sclerosis, 2) subcortical cysts, 3) osteophytes, 4) humeral migration, 5) acromioclavicular joint degeneration, 6) glenohumeral joint degeneration, and 7) subacromial spurs.

We defined cortical thickening as a tuberosity cortex thicker than that of the adjacent humeral head, and subcortical sclerosis as blurred, indistinct, thick, or dense trabeculae under the cortex (Fig. 1). To distinguish cyst-like lesions from osteoporosis and the normal lucency often seen in the greater tuberosity, we scored them only when a round or oval lucency was surrounded by a well-defined sclerotic border (Fig. 2). Humeral migration was defined as an acromiohumeral interval of < 7 mm (10). Degenerations of the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints were defined as joint space narrowing with subarticular sclerosis and osteophytes (Figs. 3, 4). Subacromial spurs are also included as radiographic abnormalities.

Abnormalities of the greater tuberosity were analyzed on AP projection and caudal 30-degree tilt view. Humeral migration was analyzed on AP projection view. Degenerations of the acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints were analyzed on AP projection and axillary lateral views. Subacromial spurs were detected as bony excrescence on supraspinatus outlet view.

Radiographic abnormalities were interpreted in random order by two third-year radiology residents, who were unaware of image details. After achieving determining inter-observer agreement, these two observers arrived at final diagnoses by consensus.

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS (IBM SPSS statistics 18.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Inter-observer agreements for the detection of radiographic abnormalities were calculated using Kappa statistics. Kappa values can be interpreted as poor (k = 0-0.20), fair (k = 0.21-0.40), moderate (k = 0.41-0.60), good (k = 0.61-0.80), and excellent (k = 0.81-1.00). The chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were used to determine relationships between rotator cuff tear types and radiographic abnormalities. Statistical significance was accepted for p values < 0.05.

Of the seven types of radiographic abnormalities diagnosed by consensus, cortical thickening with subcortical sclerosis of greater tuberosity, subcortical cysts, and osteophytes were found to be associated with the presence of a rotator cuff tear (p < 0.01).

In the 64 shoulders with a full-thickness tear, the two radiologists found greater tuberosity sclerosis in 54 shoulders, subcortical cysts in 20 shoulders, and osteophytes in 24 shoulders. In the 22 shoulders with an articular-sided partial thickness tear, they found greater tuberosity sclerosis in 10 shoulders, subcortical cysts in 3 shoulders, and osteophytes in 3 shoulders. In the 18 shoulders with a bursal-sided partial thickness tear, they found greater tuberosity sclerosis in 5 shoulders, subcortical cysts in 1 shoulder, and osteophytes in 3 shoulders. In the control group with 54 intact rotator cuffs, they found greater tuberosity sclerosis in 2 shoulders, subcortical cysts in 0 shoulder, and osteophytes in 1 shoulder.

Significant relationships were found between the above-mentioned radiographic abnormalities and specific types of rotator cuff tears, although relations were stronger for full-thickness tears than partial-thickness tears (p < 0.01). In particular, a significant relationship was found between full-thickness cuff tears and humeral migration (p < 0.01); humeral migration was observed in 13 of 64 shoulders with a full-thickness tear (Fig. 5), none of 40 shoulders with a partial-thickness tear, and in 1 of 54 shoulders with an intact rotator cuff.

Subacromial spurs were seen in 32 of 64 shoulders with a full-thickness tear, 10 of 18 shoulders with a bursal-sided partial tear, 3 of 22 shoulders with an articular-sided tear, and in 2 of 54 shoulders with an intact rotator cuff. Subacromial spur showed a significant relationship with full-thickness tear (p < 0.01) and bursal-side tear (p < 0.01) (Fig. 6). However, no significant relation was found between subacromial spur and articular-sided partial tear.

Acromioclavicular degeneration was observed in 3 of 104 shoulders with a cuff tear and in 4 of 54 shoulders with an intact rotator cuff. Glenohumeral degeneration was observed in 11 of 104 shoulders with a cuff tear and in none of 54 shoulders with an intact rotator cuff. No significant association was found between degeneration of the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints and cuff tears (Table 1).

Inter-observer agreement was moderate to substantial (Kappa values ranged from 0.45 to 0.72) for the interpretation of radiographic abnormalities (Table 2), good (k = 0.72) for the identification of subcortical cysts of the greater tuberosity, moderate (k = 0.46-0.65) for cortical thickening with subcortical sclerosis of the greater tuberosity, osteophytes of the greater tuberosity, humeral migration, subacromial spurs, and degenerations of acromioclavicular and glenohumeral joints.

Radiographic abnormalities including decreased acromiohumeral distance, a hooked acromion, and degenerative changes of the greater tuberosity and acromioclavicular joint are known to meaningfully predict the presence of rotator cuff tear (1, 2, 3, 4).

In the present study, greater tuberosity sclerosis, subcortical cysts, and osteophytes were found to be strongly associated with a cuff tear, and were more common for full-thickness tears than partial-thickness tears. These abnormal findings of the greater tuberosity indicate degeneration of greater tuberosity following chronic impingement of the shoulder joint (4), and thus, these results indicate that greater tuberosity degeneration is more related with severe rotator cuff tears. Humeral migration was also more related with a full-thickness tear, and subacromial spurs were more common for full-thickness and bursal-sided tears than articular-sided tears, which indicates extrinsic irritation of the bursal-sided supraspinatus tendon by subacromial spurs leads bursal-sided or full-thickness tears, because subacromial spurs narrow the supraspinatus outlet. On the other hand, no association was found between degeneration of the acromioclavicular or of the glenohumeral joint and cuff tears, which was expected, because earlier research showed that joint degeneration is more related to age than rotator pathology (11).

Our results concur with those of previous studies. Pearsall et al. (5) reported that shoulder radiographs of subjects with a documented rotator cuff tear showed radiographic abnormalities of the greater tuberosity, such as, sclerosis, osteophytes, and subchondral cysts. In this previously study, radiographic acromioclavicular degeneration was not found to be associated with full-thickness rotator cuff tear. Choi et al. (6) evaluated simple shoulder radiographs of 234 chronic cuff tears and 284 controls and focused on degenerations of the acromion and greater tuberosity. They reported that more degenerative changes of the greater tuberosity in simple shoulder radiographs were associated with rotator cuff tears of greater degree and size. Saupe et al. (7) evaluated the association between rotator cuff abnormalities and acromiohumeral distance, and found that tendon tears and fatty muscle degeneration of the rotator cuff correlated with reduced acromiohumeral distance. Lee et al. (8) studied examined correlations between plain radiographic findings with degree and extent of supraspinatus tear, and observed a significant relationship between a reduction in acromiohumeral distance and degree of supraspinatus tear.

On the other hand, the results of another study contradict those of the present study. Huang et al. (9) evaluated 108 shoulders by radiography and MRI, and found that cortical thickening and subcortical sclerosis were not seen more frequently in shoulders with rotator cuff disease than in normal shoulders. The authors claimed that the correlation between degeneration of the greater tuberosity and rotator cuff tears reported by previous studies were caused by study bias because the shoulders with radiographic abnormalities included were those of older subjects. In the present study, the patient and control groups were older than middle-aged; mean patient age was 62.1 years. However, we found no significant relationship between acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joint degeneration, which are age-related changes, and cuff tears, which means degeneration of the greater tuberosity is significantly related with rotator cuff tear whereas degeneration of the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joint are not.

Unlike previous studies, we divided rotator cuff tears into full-thickness tears and partial-thickness tears, and then subdivided partial-thickness tears into articular-sided and bursal-sided tears. We considered this necessary to identify associative differences between radiographic abnormalities and rotator cuff tear types.

However, the present study has several limitations. First, the control group did not consist of asymptomatic age-matched healthy volunteers, and some patients underwent shoulder arthroscopy because of various shoulder problems. Second, most members of the control group (44/54) were confirmed to have intact rotator cuffs using MR images alone. Third, retrospective design of this study could have caused selection bias.

In conclusion, radiographic abnormalities of greater tuberosity degeneration, including greater tuberosity sclerosis, subcortical cysts, osteophytes, and humeral migration, were associated with the presence of a rotator cuff tear, especially a full-thickness tear, and subacromial spurs were associated with full-thickness and bursal-sided tears.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A 42-year-old women who was diagnosed as full-thickness tear by shoulder arthroscopy. Anterior-posterior (AP) projection radiograph of the right shoulder shows cortical thickening with subcortical sclerosis in greater tuberosity (arrow).

Fig. 2

A 56-year-old men who was diagnosed as full-thickness tear by shoulder arthroscopy. Anterior-posterior (AP) projection radiograph of the right shoulder shows subcortical cyst (arrow) and osteophytes in greater tuberosity.

Fig. 3

A 69-year-old women who was diagnosed as full-thickness tear by shoulder arthroscopy. Anterior-posterior projection radiograph of the right shoulder shows degeneration of glenohumeral joint (arrow).

Fig. 4

A 65-year-old men who was diagnosed as intact rotator cuff by MR arthrography. Anterior-posterior projection radiograph of the left shoulder shows degeneration of acromioclavicular joint.

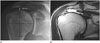

Fig. 5

A 69-year-old men who was diagnosed as full-thickness tear by shoulder arthroscopy.

A. AP projection radiograph of the right shoulder shows decreased acromio-humeral interval.

B. Oblique coronal T2-weighted image of the right shoulder shows the full-thickness defect and the torn retracted edge of the supraspinatus tendon.

Fig. 6

A 51-year-old men who was diagnosed as bursal sided partial-thickness tear by shoulder arthroscopy.

A. Supraspinatus outlet view of the right shoulder shows subacromial spur (arrow).

B. Oblique coronal T2-weighted image of the right shoulder shows irregular high signal intensity area along bursal surface of supraspinatus tendon (arrow).

References

1. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990; (254):92–96.

2. Neer CS 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983; (173):70–77.

3. Tuite MJ, Toivonen DA, Orwin JF, Wright DH. Acromial angle on radiographs of the shoulder: correlation with the impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995; 165:609–613.

4. Norwood LA, Barrack R, Jacobson KE. Clinical presentation of complete tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989; 71:499–505.

5. Pearsall AW 4th, Bonsell S, Heitman RJ, Helms CA, Osbahr D, Speer KP. Radiographic findings associated with symptomatic rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003; 12:122–127.

6. Choi JY, Yum JK, Song MC. Correlation between degree of torn rotator cuff in MRI and degenerative change of acromion and greater tuberosity in simple radiography. Clin Shoulder Elbow. 2010; 16:1–9.

7. Saupe N, Pfirrmann CW, Schmid MR, Jost B, Werner CM, Zanetti M. Association between rotator cuff abnormalities and reduced acromiohumeral distance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187:376–382.

8. Lee KR, Park JS, Jin WJ, Lee YG, Ryu KN. Plain radiographic findings of a supraspinatus tear: correlation with MR findings. J Korean Radiol Soc. 2007; 57:377–384.

9. Huang LF, Rubin DA, Britton CA. Greater tuberosity changes as revealed by radiography: lack of clinical usefulness in patients with rotator cuff disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 172:1381–1388.

10. Chopp JN, O'Neill JM, Hurley K, Dickerson CR. Superior humeral head migration occurs after a protocol designed to fatigue the rotator cuff: a radiographic analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010; 19:1137–1144.

11. Bonsell S, Pearsall AW 4th, Heitman RJ, Helms CA, Major NM, Speer KP. The relationship of age, gender, and degenerative changes observed on radiographs of the shoulder in asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000; 82:1135–1139.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download