Abstract

Syphilis has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, and the cerebral gumma is a kind of neurosyphilis which is rare and can be cured by appropriate antibiotic treatments. However, in clinical practices, diagnosis of cerebral syphilitic gumma is often difficult because imaging and laboratory findings revealed elusive results. Herein, we present a rare case of neurosyphilis presenting as cerebral gumma confirmed by histopathological examination, and positive serologic and cerebrospinal fluid analyses. This case report suggests that cerebral gumma should be considered as possible diagnosis for human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients with space-occupying lesion of the brain. And this case also provides importance of clinical suspicions in diagnosing neurosyphilis because syphilis serology is not routinely tested on patients with neurologic symptoms.

Syphilis is a complex infectious disease caused by a spirochete, Treponema pallidum (T. pallidum). It is commonly transmitted via sexual intercourses, but it can also be directly transmitted from mother to fetus. The clinical course of syphilis is classically divided into the following phases: incubation period, primary syphilis, secondary syphilis, latent syphilis, and tertiary syphilis (1, 2). Tertiary syphilis includes cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and late benign syphilis (gummatous syphilis) (1). Among these, neurosyphilis is a slow progressive, destructive infection of the brain and spinal cord (3, 4). Of the various types of neurosyphilis, the gummatous neurosyphilis that is commonly misdiagnosed as brain tumor is rare (1, 2). It is well-known that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections and syphilis are mutual risk factors responsible for the increasing incidences of neurosyphilis in HIV patients; however, the occurrence of gummatous neurosyphilis is not associated with HIV infections (1). Although cerebral gumma is a diagnostic challenge to clinicians, it is a completely curable disease by undertaking appropriate antibiotic treatments (2-4). Therefore, cerebral gumma should be included in a list of differential diagnosis for patients with space-occupying lesions of the brain. In this paper, we report a case of gummatous neurosyphilis mimicking brain tumor in a HIV-negative patient, and reviewed relevant literatures on this disease.

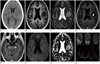

A previously healthy 55-year-old female visited the emergency department with a 3-month history of headaches and dysarthria. At admission, she was alert without any evidences of cognitive or memory disturbance, but had mild dysarthria. Both pupils showed normal light reflexes. There were no abnormal neurological findings for muscle strengths and deep tendon reflexes at the initial neurological examination. The results of the following laboratory findings were normal: complete blood count, serum electrolytes, liver function test, serum creatinine, and routine urinalysis. She underwent CT and MR imaging for evaluating brain lesions. CT scan revealed an isodense mass-like lesion with central hypodensity in the left frontal lobe with perilesional edema (Fig. 1A). MR imaging demonstrated a relatively well-circumscribed mass-like lesion with perilesional edema in the left frontal operculum, measuring 1.3 × 1.1 × 0.9 cm in size. On T1-weighted images, the mass-like lesion showed central hypointensity and peripheral isointensity (Fig. 1B). The lesion demonstrated layered signal intensities showing internal inhomogeneity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1C). A contrast enhanced T1-weighted images demonstrated peripheral ring-like enhancements of the lesion with focal non-enhancing portions in the central area (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, several small-sized enhancing nodular lesions were seen in the corticomedullary junction of both medial temporal lobes and on both sides of perimesencephalic cistern (Fig. 1E). Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) showed central hypointensity and peripheral hyperintensity with focal area of low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in the posterior portion of the lesion which strongly indicates that the lesion could be a disseminated intracranial pathology due to brain tumors or infectious diseases (Fig. 1F, G). To rule out the brain tumor, single voxel MR spectroscopy (MRS) was performed in the same portion using both short and long echo times (TE, 30 msec, 144 msec), and the results showed prominent noises probably due to the small sizes and internal inhomogeneity of the lesions. MRS with short TE demonstrated increasing lipid and lactate peaks without definite changes of choline and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) peaks whereas MRS with long TE techniques showed uninformative results due to severe noises (Fig. 1H). In contrast to the result of DWI, MRS findings indicated the possibility of a non-tumorous lesion rather than brain tumor. Therefore, surgical biopsy was performed for further confirmation of diagnosis.

On preoperative laboratory tests, her serum Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) titer was 1 : 32, and fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS) test IgG was reactive. Treponema Pallidum Hemagglutinating Assay (TPHA) was also positive (titer, 1 : 128). Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid revealed the following results: 210 white blood cells/mm3, 8 red blood cells/mm3, reactive VDRL test (titer, 1 : 8), reactive FTA-ABS IgG, and positive TPHA. Histopathological examinations revealed central necrotic materials infiltrated with eosinophils and fibrotic peripheral portions with reactive gliosis. In addition, small arterioles showed intraluminal occlusions, and the lesion did not depict spirochetes on Warthin-Starry staining. Other immunohistochemical examinations were all negative for the possibility of brain tumors such as brain metastasis, malignant lymphoma, and glioma.

The patient was finally diagnosed with cerebral gumma accompanied by neurosyphilis. Based on this diagnosis, the penicillin G benzathine was intravenously administered for 14 days, and cefotaxime with metronidazole were received intravenously for additional 10 days. Thereafter, the preexisting headaches and dysarthria had disappeared, and there were no other neurological deficits. Two months postoperatively, the gumma decreased in size and enhanced nodular lesions in the previously mentioned areas were improved on follow-ups of MR imaging. After seven months, the preexisting brain lesions disappeared completely without any newly developed brain lesions (Fig. 2).

Neurosyphilis has a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, and it can occur at any stage of syphilis infection in about 5 to 10% of untreated patients after 1 to 25 years following their infections (2). It is classified into five categories: asymptomatic, syphilitic meningitis, meningovascular syphilis, parenchymatous and gummatous neurosyphilis. Of these, the cerebral gumma is very rare and completely curable by antibiotic treatments according to reviews on relevant literatures (1, 2).

Cerebral gumma is a circumscribed mass of granulation tissues resembling granuloma, and its etiology is presumed that a localized inflammation, as an excessive response of the cell-mediated immune system, manifests as the invasion of lymphocytes and plasma cells. However, spirochetes are rarely found from tissue samples of cerebral gumma (1, 2). In the previous study, among the 156 cases with cerebral syphilitic gummas, T. pallidum was found on the histopathological staining for only one case (0.6%) (5). According to previous reports, the VDRL tests in serum are negative in 30% to 50% of all cases with neurosyphilis (6). In addition, positive VDRL test in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is highly specific for active neurosyphilis, but the test is negative for about half of neurosyphilis (2). Therefore, clinicians should be alert that normal CSF and serological analyses should not exclude neurosyphilis for HIV or non-HIV patients.

Cerebral gumma commonly arises from the dura and pia mater over the cerebral convexity or at the base of the brain and produces symptoms similar to those of other intracranial tumors (1, 2). Single or multiple masses attached to the dura mater can invade the brain parenchyma (7). The radiological findings of cerebral gumma are very inconsistent. On CT scans, the lesion was located at the periphery of brain showing low density and combined with perilesional edema (8). On MR imaging, T1-weighted images revealed a hypo- or isointense mass-like lesion, and T2-weighted images demonstrated homogeneous hyperintensity of the lesion (1, 8, 9). Differential diagnosis for cerebral gumma should be performed for other cerebral nervous system diseases including toxoplasmosis, brain tumors, bacterial and fungal infections (1, 2). All of them are rare, but more common for HIV-positive patients as compared with HIV-negative patients (2).

In the present case, the lesion demonstrated nonspecific peripheral ring-like enhancements on routine MR imaging. Furthermore, our case showed a discrepancy of the results between DWI and MRS. DWI showed central hypointensity with focal low ADC areas in the periphery of the lesion, suggesting high possibility of brain tumors. In contrast to DWI, the MRS showed increased lactate peaks without any changes of choline and NAA peaks which strongly indicate nontumorus necrotic lesions. On MRS, comparatively elevated choline peak in the contrast enhancing area represents cell membrane synthesis and destruction, and thus it is a marker of brain tumor (10). NAA peak is a marker of neuronal viability which is reduced in processes that destroy neurons (10). In addition, the lactate peak is regarded as a marker of anaerobic metabolism which no peaks are seen in normal spectra, and it is elevated in necrotic areas of brain tumor with infectious or inflammatory infiltrates (10). In the present case, MRS findings suggested that the lesion still preserved structural integrity of neurons with ongoing non-tumorous necrotic processes. Therefore, in appropriate clinical settings, the MRS can be helpful in diagnosis of cerebral gumma mimicking brain tumors. The exact mechanism of the restricted diffusion in our case is unclear. According to previous reports, cerebral gumma revealed areas of coagulative necrosis with surrounding dense inflammatory infiltrates within the lesion, and thus, restricted diffusion of the cerebral gumma may be due to cytotoxic edema of inflammatory cells, which then coagulates (11). In the present case, diffusion hypointensity may represent extensive coagulative necrosis as a main pathology of the lesion, and focal area of low ADC may contain intense inflammatory cells with cytotoxic edema.

In this case, there was no spirochete on Warthin-Starry staining whereas VDRL tests and FTA-ABS IgG were reactive with positive results of TPHA in her serum and CSF. There were also some cases in which a diagnosis was made without histopathological evidences following a suspicion of brain gumma. Suarez et al. (12) suspected the presence of brain gumma based on the results of VDRL-positive CSF cytology and presence of a hyperintense mass on T2-weighted MR images. They noted a loss of contrast enhancement in the lesions on MR images six days after the treatment with penicillin G, and radiological findings disappeared after one month, thus, confirming cerebral gumma with no histopathological evidences (12). The previous reports suggested that surgery is not always necessary for diagnosis and its treatment of cerebral gumma. From an empirical perspective, the appropriate antibiotic treatments accompanied with MRI findings of an improvement on the lesion would be useful for the diagnosis of cerebral gumma, and neurosyphilis could also be diagnosed based on the serologic tests, CSF analysis, and MR imaging (1).

In conclusion, this patient was treated with combination of antibiotics after appropriate diagnosis, and was completely recovered on follow-up after seven months. This report provides that cerebral gumma should be considered for a differential diagnosis in HIV-negative patients with space-occupying lesions in the brain, as syphilis serology is not routinely performed in patients with neurologic symptoms and it suggests that clinical suspicion of neurosyphilis is the most important for making accurate diagnosis.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

A 55-year-old woman with headache and dysarthria for 3 months.

A. CT scan reveals an isodense mass-like lesion with central hypodensity in the left frontal lobe with perilesional edema.

B. T1-weighted image shows a round mass-like lesion with central hypointensity and peripheral isointensity in the left frontal operculum.

C. T2-weighted image shows layered signal intensities with internal inhomogeneity and perilesional edema. A peripheral portion of the lesion reveals mostly isointensity whereas central portion shows mixed signal intensities.

D, E. Contrast enhanced T1-weighted images demonstrate peripheral ring-like enhancement of the lesion with focal nonenhancing area in the central portion. Small sized enhancing nodular lesions are also seen in both medial temporal areas and perimesencephalic cistern (arrows).

F, G. DWI (F) shows central hypointensity with subtle hyperintensity along peripheral portion of the lesion. ADC map (G) demonstrates no definite diffusion restriction.

H. A single voxol, short TE MRS shows increased lipid and lactate peaks around 1.3 ppm without definite change of choline peak.

Note.-ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient, DWI = diffusion weighted imaging, MRS = MR spectroscopy, TE = echo time

References

1. Lee CW, Lim MJ, Son D, Lee JS, Cheong MH, Park IS, et al. A case of cerebral gumma presenting as brain tumor in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative patient. Yonsei Med J. 2009; 50:284–288.

2. Yoon YK, Kim MJ, Chae YS, Kang SH. Cerebral syphilitic gumma mimicking a brain tumor in the relapse of secondary syphilis in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative patient. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2013; 53:197–200.

3. Jeong YM, Hwang HY, Kim HS. MRI of neurosyphilis presenting as mesiotemporal abnormalities: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2009; 10:310–312.

4. Lee MA, Aynalem G, Kerndt P, Tabidze I, Gunn R, Olea L, et al. Symptomatic Early Neurosyphilis Among HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men-Four Cities, United States, January 2002-June 2004S. JAMA. 2007; 298:732–734.

5. Fargen KM, Alvernia JE, Lin CS, Melgar M. Cerebral syphilitic gummata: a case presentation and analysis of 156 reported cases. Neurosurgery. 2009; 64:568–575. discussion 575-576.

6. Simon RP. Neurosyphilis. Arch Neurol. 1985; 42:606–613.

7. Berger JR, Waskin H, Pall L, Hensley G, Ihmedian I, Post MJ. Syphilitic cerebral gumma with HIV infection. Neurology. 1992; 42:1282–1287.

8. Agrons GA, Han SS, Husson MA, Simeone F. MR imaging of cerebral gumma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991; 12:80–81.

9. Vogl T, Dresel S, Lochmüller H, Bergman C, Reimers C, Lissner J. Third cranial nerve palsy caused by gummatous neurosyphilis: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1993; 14:1329–1331.

10. Al-Okaili RN, Krejza J, Wang S, Woo JH, Melhem ER. Advanced MR imaging techniques in the diagnosis of intraaxial brain tumors in adults. Radiographics. 2006; 26 Suppl 1:S173–S189.

11. Soares-Fernandes JP, Ribeiro M, Maré R, Magalhães Z, Lourenço E, Rocha JF. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging findings in a patient with cerebral syphilitic gumma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007; 31:592–594.

12. Suarez JI, Mlakar D, Snodgrass SM. Cerebral syphilitic gumma in an HIV-negative patient presenting as prolonged focal motor status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:1159–1160.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download