Abstract

The purpose of this study is to review various breast diseases in children and adolescents and to illustrate the sonographic findings. We reviewed the cases at our institution in order to identify breast disease in children and adolescent patients who underwent sonography and mammography. Breast disease in children and adolescents included developmental disturbance, infection, benign tumors and inherent defects. In contrast to adults, the radiologic findings of malignant breast conditions in pediatric populations have rarely been reported; however, we show ductal carcinoma in situ with juvenile fibroadenoma and rhabdomyosarcoma. During childhood and adolescence, the recognition and correct identification of physiologic breast development and specific lesions in breast entities on radiologic findings is most helpful in identifying and characterizing abnormalities and in guiding further investigation.

Since the spectrum of breast disorders during childhood and adolescence differs substantially from that of adults, knowledge of normal breast development and its variant is essential for the physician to be able to clearly recognize congenital or acquired breast disorders.

Neonatal and early childhood breast mass may arise from normal and abnormal breast development. Other causes include mastitis and axillary lymphagioma. After the onset of puberty, there are benign masses, including phyllodes tumor, juvenile fibroadenoma, physiologic condition and the developmental size problem, which are affected by hormones. Most cases of breast enlargement arise from fibroadenoma in girls and from gynecomastia in boys. There are other benign masses, such as fibrolipoma, fat necrosis, epidermoid cyst and cystic lymphangioma, originating from soft tissue rather than from the mammary tissue.

The most common malignant lesions are metastases, which are usually associated with widespread diseases. Primary breast carcinoma is very rare (1). Imaging of children and adolescent breast masses is most frequently performed for the evaluation of clinical abnormalities, such as breast enlargement or tenderness of a palpable mass or nipple skin changes. The initial imaging evaluation of a finding in children and adolescent breast is performed with sonography, whereas mammography is reserved for selected cases. The advantage of sonography over mammography is the lack of ionizing radiation in a susceptible population and great sensitivity in the relatively dense fibroglandular tissue of young girls (2). However, mammography has a role in the evaluation of microcalcifications and of suspicious discrete masses in older adolescents.

In this presentation, we present the radiologic findings of normal variants, developmental disorder as well as benign and malignant diseases that affect childhood and adolescence.

The premature thelarche is the onset of female breast development before age 7-8. As with age-appropriate thelarche, premature thelarche may be asymmetric or unilateral, in which case it may arouse a clinical concern for a neoplasm. At sonography, premature thelarche appears as normal developing breast tissue without a discrete lesion (Fig. 1) (3).

Premature thelarche may occur as an isolated event or as part of precocious puberty. Isolated premature thelarche generally occurs in girls aged 1-3 and is not progressive. Reassurance is all that is required. However, if the patient has clinical evidence of other forms of sexual maturation, such as axillary and groin hair growth or vaginal bleeding, a work-up for precocious puberty should be evaluated. Radiologic evaluation for suspected precocious puberty should include a bone age assessment and an abdominal and transvesicle pelvic sonography in order to look for evidence of maturation of the uterus and ovaries. In addition, the ovaries and adrenal glands should be evaluated for estrogen-producing lesions, including functioning ovarian cysts, juvenile granulose cell tumors of the ovary and rare feminizing adrenal cortical tumors (4).

Gynecomastia is the most common benign condition of the male breast and the most common cause of a palpable mass in the male patient. Characterized by a benign proliferation of ductal and stromal elements of the male breast tissue, it can be a unilateral or bilateral process, more often seen as bilateral (5). Numerous associations include chronic liver disease, renal failure, Klinefelter syndrome, hyperthyroidism, hormone-producing tumors and exogenous hormone ingestion (6).

Three patterns of gynecomastia have been described: nodular, dendritic and diffuse glandular, which represent various degrees of ductal and stromal proliferation. Nodular gynecomastia appears sonographically as a circumscribed discoid or triangular hypoechoic area located in the retroareolar region of the breast (Fig. 2). Dendritic gynecomastia can appear on sonography as an irregular or serpiginous hypoechoic area with fingerlike projections in the subareolar region of the breast (Fig. 3). The sonographic appearance of dendritic gynecomastia can appear suspicious and mimic malignancy. The diffuse glandular pattern of gynecomastia is associated with exogenous hormone use. The sonographic appearance of this pattern is an overall increase in the volume and echogenicity of the breast tissue pattern simulating the sonographic findings of a dense female breast (7).

Fibroadenoma is a benign fibroepithelial tumor and is the most common breast mass in girls younger than 20 years of age, accounting for well over half of the tumors in surgical series (8). Most patients present a slowly enlarging, painless mass that causes breast asymmetry. At physical examination, the mass is well-circumscribed, rubbery and freely movable; it is most often located in the upper outer quadrant (9).

Juvenile or cellular fibroadenoma is an uncommon histologic variant of fibroadenoma that frequently undergoes markedly rapid growth. A fibroadenoma over 5-10 cm in diameter is termed a giant fibroadenoma.

The typical sonographic appearance of a fibroadenoma is a well-circumscribed, round, oval or macrolobulated mass with fairly uniform hypoechogenicity (10) (Fig. 4). These masses may appear almost anechoic with low-level internal echoes (11, 12). Slender, fluid-filled clefts may be seen within juvenile fibroadenomas (Fig. 5) (12). Posterior acoustic transmission is variable and is usually enhanced or intermediate (11, 12); however, posterior shadowing has been described and may be related to infarction (10). During a color Doppler evaluation, these lesions may appear avascular or may demonstrate some internal vascularity.

It is rare for carcinoma to develop in a fibroadenoma. Fibroadenomas containing carcinomas can be indistinguishable from benign fibroadenomas. Biopsy should usually be reserved for masses with suspicious characteristics, such as indistinct margins, associated calcifications and a large increasing size. The rare carcinoma found within a fibroadenoma is likely at the in situ stage (Fig. 6) (13).

Phyllodes tumor, or cystosarcoma phyllodes, is a rare fibroepithelial neoplasm that accounts for only 1% of breast lesions in children and adolescents, but it is the most common primary mammary malignancy in this age group (8).

Phyllodes tumor shares many clinical, pathologic and imaging features with juvenile fibroadenoma. Most phyllodes tumors in adolescents are histologically benign.

The sonographic appearance of phyllodes tumor is similar to that of fibroadenoma. A well-circumscribed, round, ovoid or macrolobulated hypoechoic mass is identified, often with posterior acoustic enhancement (Fig. 7) (14, 15). The internal echotexture is frequently heterogeneous, an appearance that is less commonly observed in fibroadenoma. Anechoic cysts or clefts, findings that reflect the gross pathologic appearance of phyllodes tumors, are very suggestive of this diagnosis; however, they are not pathognomonic as they can also be seen in juvenile fibroadenoma (2, 16). The imaging findings of benign and malignant tumors overlap significantly; moreover, tissue sampling of suspect lesions is necessary for definitive diagnosis (15).

Fibrocystic changes in the breast are usually physiologic alterations that are very common in the 3rd decade of life, although such changes may be seen to some extent in late adolescence. Patients present cyclically tender breasts that are nodular at palpation (16). A spectrum of histologic findings is included under the designation of fibrocystic change. In children, solitary cysts are more common than multiple cysts. Fibrous mastopathy manifests as a solid white mass that consists of dense hypocellular to moderately cellular fibrous tissue surrounding the scattered terminal duct-lobular units. Some pathologic findings in the spectrum of fibrocystic change, such as atypical duct hyperplasia, are considered as the risk factors for subsequent breast cancer; yet, these changes are generally confined to the adult population (17).

Mastitis most commonly affects lactating women, but it also occurs in young infants and adolescents of both sexes. The underlying cause may be mammary duct obstruction or ectasia, cellulitis, an immunocompromised state or a nipple injury (17). Patients with a suppurative infection are presented with a tender, indurated, erythematous breast and possibly with fever (8). S. aureus is the most common pathogen (8, 18). At histologic analysis, acute and chronic inflammatory infiltration is noted, as well as fibrosis and occasional multinucleated giant cells (8).

Epidermoid cysts are most commonly the result of obstructed hair follicles or post-trauma, such as after an insect bite or surgery. It has been reported that it is rare for epidermoid cysts to arise from squamous metaplasia of normal columnar cells possibly found in the ductal epithelium (19). Although epidermoid cysts are of varying sizes, there have been reported cases in the breast that measure as large as 9 cm (20). On physical examination, these lesions are typically palpable.

Sonographically, epidermoid cysts appear as superficial circumscribed oval hypoechoic masses (Fig. 10). They can have an onion skin appearance corresponding to the lamellated keratin with alternating concentric hyperechoic and hypoechoic rings (21). The lesion is often seen contiguous with the skin, and occasionally, a tract may be seen leading from the lesion toward the skin.

Lymphangiomas are rare, benign congenital malformations consisting of focal proliferations of well-differentiated lymphatic tissue that are present in a multicystic or sponge like accumulation. The majority of lymphangiomas are discovered during the first 2 years of life. They are most common in the neck and axilla, and about 10% extend into the mediastinum (22). Approximately 1% of all lymphangiomas are confined to the chest (23).

On chest radiographs, lymphangiomas appear as well-defined, round, lobular masses (Fig. 11). Unilateral or bilateral pleural effusions, which are often chylous, may be present. CT usually shows a homogeneous low attenuated smooth, lobulated mass, which may mold to or envelop, rather than displace, the adjacent mediastinal structures. Lymphangiomas may be either unilocular or multilocular. Thin septations within the mass can sometimes be seen. At MR imaging, the lesions have heterogeneous signal intensity on T1-weighted images. They usually have high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, a finding that reflects their fluid content. It is sometimes easier to recognize serpentine, vessel-like septa at MR imaging than at CT (Fig. 11) (24).

A lipoma is composed of mature adipocytes and uniform nuclei that are identical to those seen in normal adult (white) fat. Additional mesenchymal elements are occasionally apparent. The most frequent nonlipomatous component is fibrous connective tissue that often predominates in septa. Prominent nonseptal fibrous components may also occur, and such lesions may be referred to as fibrolipomas (25).

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign, nonsuppurative inflammatory process that most commonly occurs subsequent to accidental iatrogenic breast trauma. The radiographic and clinical significance of fat necrosis of the breast is that it may mimic breast malignancy, requiring biopsy for diagnosis. The appearance of fat necrosis ranges from a lipid cyst to findings that are suspicious for malignancy, including clustered microcalcifications, a spiculated area of increased opacity or a focal mass (28).

The sonographic appearance of a fat necrosis is diverse. These masses may appear as a complex solid lesion with mural nodules, peripheral calcifications and fibrotic scar, and as a complex lesion with echogenic internal bands or with anechoic posterior acoustic enhancement or with shadowing when oil cysts are formed. There is no internal vascularity on the color Doppler image (Fig. 13) (29).

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast is an early, localized stage of carcinoma in the process of multistep breast carcinogenesis. The most common presentation is calcifications on mammography. DCIS is a biologically and morphologically heterogeneous disease. If left untreated, a significant proportion of these tumors will evolve into invasive cancer (30).

The most common ultrasonography (US) finding in DCIS are a microlobulated mass with mild hypoechogenicity, ductal extension and normal acoustic transmission. Spiculated margins, marked hypoechogenicity, a thick echogenic rim and posterior acoustic shadowing often suggest the presence of invasion. The main benefit of identifying a US abnormality in women with mammographically detected DCIS is to allow the use of US to guide the interventional procedures (e.g., needle biopsy, needle localization) (Fig. 6) (31).

Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most frequent soft tissue sarcoma seen in childhood and adolescence (32). Histologically, this group contains several different types of tumors, depending on the cellularity. The classification of Horn and Enterline is still generally accepted and divides rhabdomyosarcomas into four subtypes: embryonal, botryoid, alveolar and pleomorphic. In the breast, alveolar type is common. There is a strong association between alveolar histology and breast deposits (33).

On MR images of rhabdomyosarcoma, the primary tumor demonstrates nonspecific low-signal intensity with T1 weighted image and high-signal intensity with T2 weighted image. Heterogenous signal intensity representing hemorrhage in various stages of evolution may also be identified. They tend to be a multifocal and bilateral tumor on MRI and have an early ring-like enhancement of focal lesions on dynamic studies (32) (Fig. 14).

Breast lesions in children and adolescents have various ranges, which is quite different from that of adults, with the former lesions being almost benign. Sonography, combined with a clinical history and physical examination, is most important in many cases; however, the application of mammography views is necessary for the visualization of microcalcifications as well as for the evaluation of other abnormalities. Contrast enhanced CT may play a very important role in the identification and localization of the benign mass, originating from the soft tissue. Magnetic resonance imaging should be reserved for only those cases in which conventional imaging combined with clinical examination by an experienced clinician dose not result in a diagnosis. Contrast enhanced MRI is helpful for additional evaluation in cases in which there is a suspicious malignancy on conventional imaging; it is also useful for assessing the extension of the known breast cancer.

In this illustration, the differential diagnosis of breast masses in the pediatric groups is exhibited; moreover, the clinical, pathologic and imaging findings of these conditions are reviewed and correlated.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Premature thelarche, 2-year-old female baby who presented with prominent both breasts.

A, B. Sonogram (A, B) shows bilateral development of fibroglandular tissue at the subareolar area and there is no evidence of discrete lesion.

This findings are typical premature thelarche. HAND simple radiography and pelvis sonography was normal.

Fig. 2

Unilateral nodular gynecomastia, right breast, 17-year-old boy.

A. Longitudinal sonogram shows a retroareolar discoid hypoechoic area surrounding by fatty tissue at the right breast.

B. Sonogram shows normal left breast.

Fig. 3

Bilateral dendritic gynecomastia, 13-year-old boy. Transverse sonogram shows a retroareolar hypoechoic lesion, which may appear irregular finger-like projections at the both breasts.

Fig. 4

Fibroadenoma, 12-year-old girl who presented with right breast lump. Sonogram shows the well-circumscribed oval shaped, iso-to-hypoechoic mass. Histology was fibroadenoma undertaken by ultrasonography guided core biopsy.

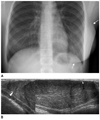

Fig. 5

Juvenile fibroadenoma, 14-year-old girl who presented with asymmetric left breast enlargement.

A. Simple chest radiography shows asymmetric huge left breast mass (arrows).

B. Sonogram shows the hyperechoic septation (arrowhead) and smaller anechoic cleft (arrow) within a huge, well-circumscribed, fairly uniform hypoechogenic mass. Histology was juvenile fibroadenoma undertaken by excisional biopsy.

Fig. 6

Cancer in situ with fibroadenoma, 18-year-old girl who presented with left palpable mass. Sonogram shows the round, macrolobulated mass with heterogenous echogenicity. Mammotome biopsy was done. Histology showed a juvenile fibroadenoma with focally irregular border and florid ductal hyperplasia. It was recommended to excise the mass completely. Excision was done 6 months later. Pathologic confirmation was ductal carcinoma in situ with a juvenile fibroadenoma with microcalcification.

Fig. 7

Benign phyllodes tumor, 15-year-old girl who presented with both rubbery breast masses.

A, B. Sonogram shows the well-circumscribed oval shaped, hypoechoic masses at the left (A) and right (B) breast. Sonogram (left and right) are similar to the appearance of a juvenile fibroadenoma. But, histology showed benign phyllodes tumor at the left breast and juvenile fibroadenoma at the right.

Fig. 8

Fibrocystic change, 17-year-old girl. Sonogram shows a lobulating contoured, well marginated, predominantly hypoechoic mass with some internal echogenic foci.

Fig. 9

Mastitis and abscess, a female baby at postnatal age of 14 days who presented with fever and erythematous breast.

A. Sonogram shows a well-circumscribed, ovoid shaped, heterogeneously hypoechoic lesion at the left subareolar area. Needle aspiration was done and S. aureus was found.

B. Follow up sonogram shows a markedly decreased extent of the lesion after antibiotic treatment during 50 days.

Fig. 10

Epidermoid cyst, 14-year-old girl who presented with a small movable left breast lump. Sonogram shows a well-circumscribed, ovoid shaped, predominantly hypoechoic mass with heterogeneous internal echotexture and no internal vascularity that is superficial in location. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy was undertaken. Histology showed an epidermoid cyst.

Fig. 11

Cystic lymphangioma, 18-year-old boy who presented with swelling of left axilla.

A. Chest radiograph shows a asymmetric left axillary swelling (arrows).

B, C. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a low-attenuated localized lobulating multiseptated cystic mass with septal wall enhancement in the left lateral chest wall and axilla, along the neurovascular bundle. There is no evidence of enhancing solid portion in the mass or no evidence of bony destruction.

D, E. Coronal T1-weighted (D) and T2-weighted (E) MR image shows a cystic mass with multiple septa (arrows). Histology showed cystic lymphangioma taken by excisional biopsy.

Fig. 12

Fibrolipoma, 6-year-old girl who presented with right breast lump. Sonogram shows the well-circumscribed oval shaped, heterogenous hyperchoic mass.

Fig. 13

Fat necrosis, 16-year-old boy who presented with right chest wall palpable mass after having minor blunt trauma by a soccer ball.

A. Sonogram shows an encapsulated, well-circumscribed, beaded shaped, heterogenously isoechoic lesion at the right subareolar area. There is no breast parenchymal tissue. Sonography guided core biopsy (14 G automated gun) was undertaken and histology showed fat necrosis with fibroconnective tissue.

B. Color Doppler image shows no internal vascularity with the lesion.

Fig. 14

Rhabdomyosarcoma, 21-year-old women.

A. Sonogram shows a huge, irregular shape, indistinct marginated heterogenous hypoechoic mass in left breast lower inner quadrant.

B. MR image shows multifocal infiltrating, ill-defined mass with intermediate signal intensity on T1 weighted image and high signal intensity on T2 weighted image (not shown). Post-contrast enhanced MR image shows ring-like enhancing mass with early rapid contrast enhancement and delayed washout. Histology showed embryonal type of rhabdomyosarcoma.

References

1. Bock K, Duda VF, Hadji P, Ramaswamy A, Schulz-Wendtland R, Klose KJ, et al. Pathologic breast conditions in childhood and adolescence: evaluation by sonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2005. 24:1347–1354. quiz 1356-1357.

2. Venta LA, Dudiak CM, Salomon CG, Flisak ME. Sonographic evaluation of the breast. Radiographics. 1994. 14:29–50.

3. Siegel MJ. Siegel MJ, editor. Chest. Pediatric sonography. 2002. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;201–211.

4. Chung EM, Cube R, Hall GJ, González C, Stocker JT, Glassman LM. From the archives of the AFIP: breast masses in children and adolescents: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009. 29:907–931.

5. Kopans DB. Breast Imaging. 1997. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;497–505.

6. Stavros AT. Evaluation of the male breast. Breast Ultrasound. 2004. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;712–714.

7. Yitta S, Singer CI, Toth HB, Mercado CL. Image presentation. Sonographic appearances of benign and malignant male breast disease with mammographic and pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2010. 29:931–947.

8. Coffin CM. Stocker JT, Dehner LP, editors. The breast. Pediatric pathology. 2002. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;207–208.

9. Goel NB, Knight TE, Pandey S, Riddick-Young M, de Paredes ES, Trivedi A. Fibrous lesions of the breast: imaging-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005. 25:1547–1559.

10. Rosai J. Rosai J, editor. Breast. Rosai and Ackerman's surgical pathology. 2004. 9th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby;1769–1773.

11. Cole-Beuglet C, Soriano RZ, Kurtz AB, Goldberg BB. Fibroadenoma of the breast: sonomammography correlated with pathology in 122 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983. 140:369–375.

12. Kronemer KA, Rhee K, Siegel MJ, Sievert L, Hildebolt CF. Gray scale sonography of breast masses in adolescent girls. J Ultrasound Med. 2001. 20:491–496.

13. Baker KS, Monsees BS, Diaz NM, Destouet JM, McDivitt RW. Carcinoma within fibroadenomas: mammographic features. Radiology. 1990. 176:371–374.

14. Vade A, Lafita VS, Ward KA, Lim-Dunham JE, Bova D. Role of breast sonography in imaging of adolescents with palpable solid breast masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008. 191:659–663.

15. Yilmaz E, Sal S, Lebe B. Differentiation of phyllodes tumors versus fibroadenomas. Acta Radiol. 2002. 43:34–39.

16. Liberman L, Bonaccio E, Hamele-Bena D, Abramson AF, Cohen MA, Dershaw DD. Benign and malignant phyllodes tumors: mammographic and sonographic findings. Radiology. 1996. 198:121–124.

17. Greydanus DE, Matytsina L, Gains M. Breast disorders in children and adolescents. Prim Care. 2006. 33:455–502.

18. Pettinato G, Manivel JC, Kelly DR, Wold LE, Dehner LP. Lesions of the breast in children exclusive of typical fibroadenoma and gynecomastia. A clinicopathologic study of 113 cases. Pathol Annu. 1989. 24(Pt 2):296–328.

19. Chantra PK, Tang JT, Stanley TM, Bassett LW. Circumscribed fibrocystic mastopathy with formation of an epidermal cyst. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994. 163:831–832.

20. Taira N, Aogi K, Ohsumi S, Takashima S, Kawamura S, Nishimura R. Epidermal inclusion cyst of the breast. Breast Cancer. 2007. 14:434–437.

21. Crystal P, Shaco-Levy R. Concentric rings within a breast mass on sonography: lamellated keratin in an epidermal inclusion cyst. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005. 184:3 Suppl. S47–S48.

22. Faul JL, Berry GJ, Colby TV, Ruoss SJ, Walter MB, Rosen GD, et al. Thoracic lymphangiomas, lymphangiectasis, lymphangiomatosis, and lymphatic dysplasia syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000. 161(3 Pt 1):1037–1046.

23. Brown LR, Reiman HM, Rosenow EC 3rd, Gloviczki PM, Divertie MB. Intrathoracic lymphangioma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986. 61:882–892.

24. Miyake H, Shiga M, Takaki H, Hata H, Onishi R, Mori H. Mediastinal lymphangiomas in adults: CT findings. J Thorac Imaging. 1996. 11:83–85.

25. Weiss S, Goldblum J. Benign lipomatous tumors: Enzinger and Weiss's soft tissue tumors. 2001. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby;571–639.

26. Kransdorf M, Murphey M. Lipomatous tumors. Imaging of soft tissue tumors. 1997. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;57–101.

27. Murphey MD, Carroll JF, Flemming DJ, Pope TL, Gannon FH, Kransdorf MJ. From the archives of the AFIP: benign musculoskeletal lipomatous lesions. Radiographics. 2004. 24:1433–1466.

28. Hogge JP, Robinson RE, Magnant CM, Zuurbier RA. The mammographic spectrum of fat necrosis of the breast. Radiographics. 1995. 15:1347–1356.

29. Soo MS, Kornguth PJ, Hertzberg BS. Fat necrosis in the breast: sonographic features. Radiology. 1998. 206:261–269.

30. Sakorafas GH, Tsiotou AG. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) of the breast: evolving perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000. 26:103–125.

31. Moon WK, Myung JS, Lee YJ, Park IA, Noh DY, Im JG. US of ductal carcinoma in situ. Radiographics. 2002. 22:269–280. discussion 280-281.

32. Agrons GA, Wagner BJ, Lonergan GJ, Dickey GE, Kaufman MS. From the archives of the AFIP. Genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma in children: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1997. 17:919–937.

33. Yang WT, Muttarak M, Ho LW. Nonmammary malignancies of the breast: ultrasound, CT, and MRI. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2000. 21:375–394.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download