Abstract

The colonoscopy has been used to diagnose various colonic lesions. However, this method has its limitations in diagnosing and differentiating subepithelial tumors. For this reason, the role of cross-sectional radiologic imaging is important for the diagnosis of colonic subepithelial tumors. Moreover, although these tumors are associated with a wide range of radiologic features, they may have unique radiologic features that suggest a specific diagnosis. Hemangiomas typically show transmural colonic wall thickening with phleboliths in intramural or extracolic areas. Colonic lymphangiomas manifest as a multilocular cystic mass at CT and sonography. Colonic lipomas are well demonstrated by CT because the masses were present with characteristic fatty density. Schwannomas usually appear as well circumscribed, homogeneous masses with low attenuation at CT. The primary form of colonic lymphoma has a wide variety of radiologic types, including a polypoid mass, circumferential mural mass, and a cavitary mass. Small gastrointestinal stromal tumors are usually homogeneous, whereas larger tumors tend to have a heterogeneous appearance with central necrosis at contrast-enhanced CT scans. Neuroendocrine tumors of the colon are most frequently observed in the rectum and are typically small incidental lesions. Familiarity with these imaging features can help distinguish particular disease entities.

Colonic subepithelial tumors are rare, and therefore, are not encountered as often in daily practice as are adenomas and carcinomas of the colon. Furthermore, they may not cause symptoms before attaining large size. When small in size, colonic subepithelial tumors are incidentally detected on a colonoscopy or cross-sectional images. A wide variety of benign and malignant primary subepithelial tumors may arise from the colonic wall. Some tumors such as lipomas, neuroendocrine tumors, hemangiomas, and lymphomas originate in the superficial location on the colon wall. Other tumors such as a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) arise from the deeper part of the muscularis propria and often demonstrate an exoenteric growth pattern (1). In this article, we present a variety of radiologic findings from benign and malignant subepithelial tumors of the colon, and correlate them with their corresponding colonoscopic and pathologic findings.

Colonic hemangiomas are uncommon benign lesions arising from the subepithelial vascular plexus, and are attributable to the embryonic sequestration of mesodermal tissue. The clinical manifestations usually include acute or recurrent chronic painless rectal bleeding in a young adult. Colonic hemangiomas are classified as cavernous and capillary subtype tumors. Approximately 80% of colonic hemangiomas are cavernous subtype, 50% to 70% of which are located in the rectosigmoid colon. Cavernous hemangiomas are composed of large multilobulated thin-walled vascular channels with no capsules, which typically have full-thickness mural involvement, often with infiltration into the surrounding connective tissue (2) (Fig. 1A). At optical colonoscopy, the lesions appear as dilated subepithelial vascular tumors, which are typically soft, ranging in color from deep wine to plum, and are associated with mucosal congestion and edema (Fig. 1B). In addition, these tumors collapse easily on insufflation. Moreover, the presence of phleboliths on plain abdominal radiographs is an important diagnostic clue observed in 26-50% of adult patients (Fig. 1C). Barium enemas expose nonspecific polypoid or multilobular annular masses that may collapse with air insufflations (2) (Fig. 1D). In addition, CT scans can ensure the accurate diagnosis, which includes inhomogeneously enhancing transmural bowel-wall thickenings containing phleboliths (Fig. 1E). On MR imaging, the colonic wall is markedly thickened with high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. This feature appears to be related to the slow blood flow in hemangiomas. T1-weighted image shows homogeneous, hypointense colonic wall thickening and MR image after a gadolinium injection reveals heterogeneous enhancement of the both colonic wall and pericolic area.

Lymphangiomas of the colon are rare benign lesions with only 331 cases reported in the world medical literature between 1931 and 2004. They are described as congenital malformations of the lymphatic system and are considered to be lymphatic hamartomas. Although the peak incidence of colonic lymphangiomas is in the seventh decade, the age distribution did not demonstrate that the disease is related to aging. Clinical symptoms are not specific and include mild to intense abdominal pain, altered bowel habitus, and rectal bleeding. The occurrence of intussusception caused by a colonic lymphangioma is extremely rare, with an incidence of only 3 cases out of 79 (4%). Lymphangiomas are masses consisting of endothelial cells and supporting connective tissue that are classified into three categories: simple, cavernous, and cystic. Moreover, round cells, islands of fat cells and smooth muscle are usually present. The colonoscopic appearance suggests that the presence of a lymphangioma is in the form of a round and smooth, broad based, pinkish color, translucent, tension, and lustrous surface (Fig. 2A). Lymphangiomas show changes in shape caused by peristalsis, compression, and patient position. These lesions are seen as sharply marginated, oval, or round colonic defects on a barium study. They usually are pliable, readily changing in shape in response to compression or peristaltic activity during a barium study. CT and sonography properly demonstrate the multilocular cystic mass with internal septa (3) (Fig. 2B, C). Segmental resection seems to be the treatment of choice, except for pedunculated or small lymphangiomas.

Colonic lipomas are relatively rare and most commonly occur in the nonepithelial submucosal layer of the colon. The most common location for colonic lipomas is the cecum or ascending colon. Most lipomas are asymptomatic, but large lipomas may cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, hemorrhage, and intussusception (4). Lipomas are composed of well-differentiated adipose tissue originating in the submucosa. At optical colonoscopy, the classic characteristics of lipomas include a yellowish pale color and soft to the touch when probing with a blunt instrument (Fig. 3A, B). A Barium enema shows a well-defined, smooth intraluminal filling defect, as well as a change in shape under peristalsis (squeeze sign). These findings are suggestive of lipomas, but do not provide the conclusive evidence for a correct diagnosis. Colonic lipomas are well demonstrated by CT because the mass has a typical fat density between -70 and -120 HU (4) (Fig. 3C). On MRI, the typical features of lipomas are a fatty mass with increased signal intensity in the T1-weighted image and intermediately intense to hyperintense in the T2-weighted fast spin-echo image relative to muscle. Fat saturation and chemical shift imagings are useful imaging techniques for differentiating lipoma from non-fatty masses (4). If a patient is asymptomatic, treatment is not necessary; however, endoscopic removal or surgical resection may be required for a large complicated lipoma.

Schwannomas of the colon are extremely rare with only a small number of cases having been reported in the literature, with average age at presentation of 65 years. Colonic shawannomas have been reported, in descending order of frequency, in the cecum, sigmoid, rectosigmoid junction, transverse colon, descending colon, and rectum. Schwannoma usually grow slowly, so most patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. Large schwannomas may cause latent or acute bleeding, bowel obstruction, constipation, and abdominal pain. Macroscopically, schwannomas appear as a spherical, solid, and well-encapsulated tumor that is gray in color. Mucosal ulceration is often visible, but necrosis and hemorrhage are not typical features. Histopathologically, schwannomas are composed of elongated bipolar spindle cells with zonally variable cellularity and a focally prominent nuclear palisading pattern. Immunohistochemistrically, schwannomas are strongly positive for S-100 and are constantly negative for CD117 (KIT), which differs from GISTs. The combination of a positive S-100 and negative KIT establishes the diagnosis of schwannomas. Radiographically, this tumor has imaging characteristics similar to those of colonic GISTs. A Barium study demonstrates the presence of an intraluminal or subepithelial mass, possibly with ulceration of the overlying mucosa. Further, schwannoma manifest as a nonspecific soft tissue attenuated mass at CT (Fig. 4). However, the lack of hemorrhage, necrosis, and degeneration at CT was believed to be helpful in distinguishing schwannomas from GISTs, where these findings typically occur (5).

Inflammatory fibroid polyp (IFP) is an uncommon benign polypoid lesion of the gastrointestinal tract. Most cases of IFP are located in the stomach and small bowel, but a colonic occurrence is rare. Most colonic IFPs tend to be found in the right colon. The clinical manifestation may rely on the gross morphology of the lesion and its location in the gastrointestinal tract. The major clinical symptoms include abdominal pain, bloody stools, weight loss, diarrhea, and anemia. A large IFP may cause intestinal obstruction or intussusception. Macroscopically, an IFP is a smooth sessile or pedunculated polyp. Microscopically, it is composed of loose connective tissue with abundant inflammatory cells including plasma cells and eosinophils. Immunohistochemically, the stromal cells of IFPs are often CD34-immunoreactive, but do not stain for KIT. Endoscopically, IFPs appear to have a smooth sessile or pedunculated configuration with most cases having erythematous or ulcerative mucosa (Fig. 5A). A Barium enema reveals the pedunculated or sessile mass, but with no distinct radiologic features. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows low attenuated, homogeneous intraluminal or intramural mass, but there is no unique CT finding that will aid in the diagnosis of an IFP (6) (Fig. 5B). For the treatment of symptomatic IFPs, surgical resection has been performed in most cases. However, in the case of small pedunculated lesions, treatment can be administered in the form of an endoscopic polypectomy.

Primary lymphoma of the large bowel accounts for 0.4% of all tumors of the colon, and colorectal lymphomas constitute 6-12% of gastrointestinal lymphomas. Dawson's diagnostic criteria for primary intestinal lymphomas require the absence of lymphadenopathy, normal chest radiography, normal complete blood count, predominance of the bowel lesion at laparotomy, and the absence of tumor in the liver and spleen (7). Most cases consisted of males in the 5th to 7th decades. Immunosuppression and inflammatory bowel disease are known to be associated with the development of primary colorectal lymphomas. The most common location for the occurrence of primary colorectal lymphoma is the cecum, followed by the rectum. The clinical manifestations are often nonspecific; however, the two most common symptoms include abdominal pain and weight loss. Obstruction is rare because it does not elicit a desmoplastic response, and subepithelial lymphoid infiltration weakens the muscularis propria of the wall (7). Nearly all occurrences of primary lymphoma of the large bowel are non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas. Imaging manifestations of colonic lymphomas included polypoid masses, which occurred most frequently near the ileocecal valve (Fig. 6); 2) circumferential infiltration (Fig. 7); 3) a cavitary mass excavating into the mesentery; 4) endoexoenteric tumors; 5) mucosal nodularity; and 6) fold thickening. Polypoid lesions may be predisposed to experience intussusception, have homogeneous intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted MR images, and heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Mild to moderate enhancement is seen after the intravenous administration of gadolinium-based contrast material (7). Treatment usually consists of surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy.

GISTs of the colon are extremely rare, consisting of only about 0.1% of colon and rectal tumors. The most common site of colonic GISTs is the anorectum. GI bleeding, constipation, rectal or pelvic pain, obstruction, and a mass on examination are the most common initial symptoms. GISTs are typically well circumscribed masses without a true capsule. Moreover, they exhibit a propensity for exophytic growth because they usually involve the outer muscular layer (8). Focal areas of hemorrhage, cystic degeneration, and necrosis may occur, particularly in large lesions (Fig. 8A). GISTs can be histologically classified by their predominant cell morphology, consisting of either a spindle cell or epithelioid (8). Immunohistochemically, GISTs are positive for KIT (CD117), and as a result, a definite diagnosis of GISTs now relies upon a tumor's positive expression of KIT. The most commonly cited characteristics indicative of a malignancy include tumor size and mitotic activity (8). The GIST Workshop created a consensus recommendation of risk assessment based on tumor size and number of mitoses (8). These guidelines are now being updated after the publication of very large studies by Miettinen and colleagues who found that small bowel or colonic GISTs show a much higher rate of aggressive behavior than gastric GISTs. According to updated guideline, tumors greater than 2 cm with greater than 5 mitoses per 50 HPF or a size greater than 10 cm with any mitotic rate, indicates a high risk for malignancy in colonic GISTs. Colorectal GISTs may have a broad based appearance that is subtle and nonspecific at colonoscopy because they tend to exhibit exoenteric growth and only rarely demonstrate a prominent intraluminal component (9). Most lesions are shown as extraluminal or intramural masses at CT. Smaller tumors are usually homogeneous, whereas larger tumors tend to have a heterogeneous appearance with necrosis or hemorrhage. Prominent enhancement of a tumor is typical on contrast- enhanced CT imaging (Fig. 8B) and it usually has not undergone a lymphadenopathy. MRI findings of GISTs show low-intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (Fig. 8C, D). Furthermore, GISTs show intense, heterogeneous enhancement (9) (Fig. 8E). Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for colonic GISTs. However, recurring and metastatic tumors of the peritoneum or liver can effectively be treated with imatinib mesylate (8).

Neuroendocrine tumors of the colon are uncommon, with most cases arising in the rectum and fewer cases occurring in the cecum. Abdominal pain and weight loss are typical symptoms for neuroendocrine tumors of the proximal colon, whereas more than 50% of patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors are asymptomatic and the lesions are discovered at routine rectal examination or screening colonoscopy (Fig. 9A). Pathologically, serotonin-producing EC-cell neuroendocrine tumors of the cecum mimic cecal adenocarcinomas in that they are frequently large, polypoid, or ulcerating masses. L-cell rectal carcinoids are usually solitary, small, subepithelial nodules or have focal areas of plaque-like thickening. Neuroendocrine tumors of the proximal colon are polypoid intraluminal masses that are indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma at CT. Rectal carcinoids are commonly seen as small mural or polypoid masses at CT (10) (Fig. 9B, C).

Malignant subepithelial tumors of the colon, other than GISTs, include leiomyosarcomas and malignant schwannomas. Leiomyosarcomas are extremely rare and are often large and ulcerative by the time they are detected (1) (Fig. 10). They arise from smooth muscle cells of the colonic wall and suppose less than 1% of the malignant colorectal tumors. Presenting symptoms and endoscopic findings may be non-specific. On immunohistochemical study, the c-KIT determination is negative unlike the GISTs, whereas they are positive for actin, vimentin and desmin. They are aggressive tumors with a high local recurrence rate as well as having significant hematogeneous spread, the liver being the most affected organ.

Subepithelial tumors of the colon represent a wide range of benign and malignant tumors, some of which have similar radiologic features that make differentiation difficult. However, despite overlaps in the radiologic findings, some tumors have characteristic radiologic features that may suggest a specific diagnosis. Therefore, it is important that radiologists are familiar with tumors that have unique radiologic findings. Lastly, awareness of the various radiologic findings in colonic subepithelial tumors can help ensure a correct diagnosis and proper management of the condition.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Hemangioma of the descending colon in a 34-year-old woman.

A. Photograph of the resected specimen demonstrates a lobulated subepithelial mass with areas of focal hemorrhage and multiple phleboliths.

B. Colonoscopic image shows dilated subepithelial vascular masses with a deep wine color associated with mucosal congestion and edema.

C. Plain radiograph shows multiple phleboliths (arrows) along the descending colon.

D. Barium study reveals lobulated contour masses (arrows) with multiple phleboliths along the proximal portion of the descending colon.

E. Contrast-enhanced CT scan reveals circumferential mural thickening with multiple phleboliths in the descending colon (arrows).

|

| Fig. 2Lymphangioma of the colon in a 33-year-old woman.

A. Photography from endoscopy reveals a pedunculated subepithelial mass covered with erythematous mucosa in the sigmoid colon.

B. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a well-defined low attenuated cystic mass in the sigmoid colon (arrow).

C. Transabdominal sonogram shows an anechoic cystic mass in the sigmoid colon (arrow).

|

| Fig. 3Lipoma of the sigmoid colon in a 51-year-old man.

A. Colonoscopic image shows a yellowish subepithelial mass.

B. The mass reveals a cushion sign at compression with a blunt instrument.

C. Axial CT scan shows a well-defined fatty mass in the sigmoid colon (arrow).

|

| Fig. 4Schwannoma of the cecum in a 44-year-old man. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a homogeneously enhancing, exoenteric growing mass (arrow) in the posterior wall of the cecum. |

| Fig. 5Inflammatory fibroid polyp of the ascending colon in a 35-year-old man.

A. Photograph from endoscopy reveals a subepithelial mass with a smooth mucosal surface (arrow).

B. Contrast-enhanced CT shows a well-defined, homogeneously low attenuated mass with intact overlying mucosa (arrow) in the ascending colon.

|

| Fig. 6Polypoid primary lymphoma of the cecum in an 18-year-old man.

A. Barium study reveals a lobulated filling defect with a "coiled spring" appearance in the hepatic flexure of the colon (arrow).

B. Transabdominal sonogram shows a well-defined hypoechoic mass (arrow) with intussusception of the ascending colon.

C. Corresponding contrast-enhanced CT scan shows the inhomogeneously enhancing mass combined with intussusception within the ascending colon.

D. Photograph of the resected specimen shows a well-demarcated fungating mass with focal ulceration in the cecum.

|

| Fig. 7Circumferential infiltrative primary lymphoma of the rectum in a 29-year-old man.

A. Pre-contrast CT scan shows low attenuated circumferential mural thickening of the rectum.

B. Contrast-enhanced CT scan reveals poor contrast enhancement of the lesion.

C. Barium study demonstrates segmental luminal narrowing with lobulated contour defect (arrows) in the rectum.

|

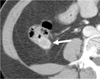

| Fig. 8Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the rectum in a 56-year-old man.

A. Photograph of the resected specimen shows intramural mass with intact overlying mucosa in the rectal wall.

B. Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows an exoenteric growing mass with inhomogeneous enhancement in the anterior wall of the rectum.

C. T1-weighted axial image.

D. T2-weighted sagittal image.

E. Gd-enhanced fat suppressed T1-weighted image demonstrate a well-defined exoenteric subepithelial mass with heterogeneous enhancement (arrows).

|

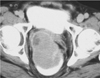

| Fig. 9Neuroendocrine tumor of the rectum in a 55-year-old woman.

A. Colonoscopic image reveals a small subepithelial mass (arrow) with intact overlying mucosa in the lower rectum.

Axial (B) and coronal (C) reformatted CT images show a small well-enhancing subepithelial mass (arrows) in the lower rectum.

|

References

1. Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Menias CO, Gopal DV, Arluk GM, Heise CP. Evaluation of submucosal lesions of the large intestine: part 1. Neoplasms. Radiographics. 2007; 27:1681–1692.

2. Hsu RM, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Diffuse cavernous hemangiomatosis of the colon: findings on three-dimensional CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 179:1042–1044.

3. Wan YL, Lee TY, Hung CF, Ng KK. Ultrasound and CT findings of a cecal lymphangioma presenting with intussusception. Eur J Radiol. 1998; 27:77–79.

4. Genchellac H, Demir MK, Ozdemir H, Unlu E, Temizoz O. Computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings of asymptomatic intra-abdominal gastrointestinal system lipomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008; 32:841–847.

5. Levy AD, Quiles AM, Miettinen M, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal schwannomas: CT features with clinicopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 184:797–802.

6. Harned RK, Buck JL, Shekitka KM. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: radiologic evaluation. Radiology. 1992; 182:863–866.

7. Ghai S, Pattison J, Ghai S, O'Malley ME, Khalili K, Stephens M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma: spectrum of imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2007; 27:1371–1388.

8. Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003; 23:283–304. 456quiz 532.

9. Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: CT and MR imaging features with clinical and pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003; 180:1607–1612.

10. Levy AD, Sobin LH. From the archives of the AFIP: Gastrointestinal carcinoids: imaging features with clinicopathologic comparison. Radiographics. 2007; 27:237–257.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download