Abstract

Purpose

To clarify the relationship between the pattern of cholecystolithiasis and the gross features of segmental adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder.

Materials and Methods

Fifty-five consecutive patients with segmental adenomyomatosis with calcified gallbladder stones defined on CT were retrospectively analyzed in terms of (i) stone location (fundal vs. neck compartment) and (ii) size of the largest stone as a function of the extent of segmental mural thickening (type A, limited at the narrow segment; type B, partially extended in the fundal direction; type C, involving the entire fundal compartment). The extent of segmental mural thickening in patients with cholecystolithiasis was compared with a control group (n = 48) lacking stones.

Results

Stones were found more frequently in the fundal compartment in 48 patients compared to the neck compartment in 12 patients (p<0.001). The mean size of the largest stone in type C (5.4 ± 4.9 mm) was larger than in type A (2.3 ± 2.2 mm) (p=0.033). In patients with cholecystolithiasis, type C segmental thickening was predominant (69%) compared to the control group (42%) (p=0.012).

Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder (GB) is defined as the epithelial proliferation and hypertrophy of the muscularis of the gall bladder (1). Although it is a relatively common disease, with a reported incidence around 5% (2), its pathogenesis and cause have not been clearly defined. Adenomyomatosis is usually classified into three morphologic types including segmental, fundal or diffuse type according to the involved area of GB wall thickening (1).

Adenomyomatosis is considered to be a clinically benign condition (3), but identifying the clinical implications of adenomyomatosis has been challenging (45). Nishimura et al. determined that the segmental type of adenomyomatosis plays an important role in lithogenesis related to biliary stasis in the fundal compartment, which is distinguished from other types of adenomyomatosis (6). Depending on clinical practices of daily CT interpretation, many cases of segmental adenomyomatosis are identified that show a non-neoplastic, thickened, narrowed segment dividing the lumen into two compartments including the fundal (distal to the narrowed segment) and neck (proximal to the narrowed segment) compartments (7). Cholecystolithiasis and a variable extent of inflammatory mural thickening are usually combined in such cases; however, most of the surgically confirmed lesions are reported to have chronic cholecystitis omitting a detailed description about the presence or extent of segmental adenomyomatosis in the histological report.

In the present study, we attempted to categorize segmental adenomyomatosis based on the presence of GB stones and the extent of mural thickening, and tried to clarify the relationship between the pattern of cholicystolithiasis and the gross features, defined on CT, of segmental adenomyomatosis of the GB.

This retrospective study was approved by our Committee for Clinical Investigations and conducted according to institutional review board rules for departmental review of research records. Informed consent from subjects was waived. Search of the hospital information system records and medical records over a 39-month period (from July, 2006 to October, 2009) identified a total of 55 patients (28 men, 27 women; mean age, 56 years; age range, 29-83 years) with segmental adenomyomatosis and GB stones. For comparative analysis, another 48 consecutive patients (23 men, 25 women; mean age, 54 years; age range, 22-78 years) showing segmental adenomyomatosis without calcified stones on CT during the same period were selected as a control group. The possibility of a neoplastic condition was excluded by follow-up imaging after at least 1 year (n=79) or surgical operation (n=24).

Unenhanced and contrast material-enhanced abdomen or abdomen-pelvis computed tomography (CT) examination was performed using a 64-MDCT scanner (Somatom Sensation 64, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). Scanning was performed craniocaudally using the following parameters: detector configuration, 0.6 × 64 mm; effective section thickness, 3.0 mm; reconstruction interval, 3.0 mm; gantry rotation time, 0.33 sec; pitch, 1.0; effective mAs, 250; and kVp, 120. Each image acquisition was performed during one breath-hold of up to 10 sec, depending on the scan range. All patients received 2 mL/kg of iodinated contrast agent (Ultravist 300; Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) intravenously. After unenhanced imaging of the upper abdomen, a warmed contrast medium was administered using an automatic injector (EnVisionCT; Medrad Inc, Pittsburgh, PA, U.S.A.) at a rate of 1.5 mL/s through an 18-gauge IV catheter inserted into an arm vein. Scan start time was 20 seconds after completion of the contrast injection. Axial section data were reconstructed for unenhanced and contrast material-enhanced scanning: first with 5 mm thick sections at 5.0 mm intervals in the transverse plane, then with 0.6 mm thick sections at 0.6 mm intervals. The second set of reconstructed axial scans was then reformatted in the coronal plane with 2.0 mm sections at 2.0 mm intervals. All images were routinely transferred to a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) as a separate series of scans.

Two observers (one attending staff with 15 years experience in abdominal radiology and one second year resident in the department of radiology) retrospectively reviewed the CT images of all patients having segmental adenomyomatosis of the GB with (Group 1, n=55) or without (Group 2, n=48) cholecystolithiasis. For Group 1 patients, stone location (fundal vs. neck compartment) was determined and the size of the largest stone in each compartment was measured. Some patients (n=5) that had stones in the fundal portion and neck portion simultaneously, and those patients were included with groups of patients having stones only in the fundal compartment (n=43) and only in the neck compartment (n=7). The longest dimension of the largest stone was measured using electronic calipers on an axial view by each observer, and the mean value of the two measurements was used for further analysis. Stones less than 1.0 mm were defined as not measurable. Segmental adenomyomatosis was categorized into three types according to the extent of segmental thickening determined by the two observers in consensus as follows: type A, limited at the narrow segment; type B, partially extended in the fundal direction; type C, involving the entire fundal compartment of the GB wall (Fig. 1). The patterns of segmental thickening were compared between groups.

In Group 1 patients, stone location was compared between fundal and neck compartments using a chisquare test. For the three different segmental adenomyomatosis types, depending on the extent of mural thickening, the mean sizes of the largest stones were compared using Student's t test. Non-measurable (small) stones were not included in the comparison. Relative prevalences of the three different types by the extent of mural thickening was compared between the two groups using a chi-square test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In Group 1 cholecystolithiasis patients, stones were found more frequently in the fundal compartment of 48 patients compared with the neck compartment in 12 patients (p < 0.001). The mean size of the largest stones in type C (5.4 ± 4.9 mm) was significantly larger (p=0.033) than in type A (2.3 ± 2.2 mm), but was comparable (p=0.613) with that in type B (4.3 ± 4.1 mm) (Figs. 2, 3).

For the type of segmental adenomyomatosis according to the extent of mural thickening in Group 1 patients, 11 were type A (20%), 6 were type B (11%) and 38 were type C (69%) (Figs. 2, 3). In Group 2 patients without cholecystolithiasis (Fig. 4), 22 were type A (46%), 6 were type B (13%) and 20 were type C (42%). The most common morphologic type of segmental adenomyomatosis of the GB at CT was type C in both groups regardless of the presence of cholecystolithiasis. However, type C was significantly more prevalent in Group 1 compared with Group 2 (p=0.012) (Fig. 2).

Adenomyomatosis of GB may be asymptomatic or associated with clinical symptoms of chronic cholecystitis when revealed on imaging studies (1). Ever since imaging findings of adenomyomatosis has been described (891011), radiological and clinical concerns have been limited to the differential diagnosis of adenomyomatosis from GB cancer (12). Recently, through bile analysis, Nishimura et al. suggested that segmental adenomyomatosis could be a predisposing factor for stone formation due to bile stasis (6). Cholecystolithiasis is a major cause of cholecystitis (1314) and several reports revealed that chronic cholecystitis can be a predisposing factor for cancer (15). Therefore, segmental adenomyomatosis should not be overlooked as a possible clinical complication, although the direct association of adenomyomatosis and adenocarcinoma is unclear (16).

Adenomyomatosis of the GB, also referred to as adenomyomatous hyperplasia or intramural diverticulosis, is an acquired hyperplastic lesion of the GB. It is characterized by excessive proliferation of surface epithelia with invaginations into the thickened, hypertrophied muscularis propria, also known as Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses (12). The three classic types of adenomyomatosis are segmental, fundal, and diffuse, depending on the location of the mural thickening. To our knowledge, there has been no histopathologic definition of segmental adenomyomatosis that clearly defines the extent of segmental wall thickening in each type. The results of the present study evaluating stone location in GB with segmental adenomyomatosis on CT are in accord with a previous theory of a connection between the stone formation and bile stasis (6). Moreover, we determined the relationship between the extent of mural thickening and the presence of GB stones in the fundal compartment through comparisons between the two patient groups with and without cholecystolithiasis.

Because the prognosis is controversial, it is very unusual for any surgical intervention to occur after imaging-based diagnosis of adenomyomatosis itself, but surgical treatments are often considered in cases associated with stones or cholecystitis (3). However, histopathologic and imaging correlations of adenomyomatosis is not possible in most cases because pathology reports tend to omit detailed descriptions of the existence or extent of adenomyomatosis. In clinical practice, segmental mural thickening of the GB with contrast enhancement can be interpreted as either chronic inflammatory change or segmental adenomyomatosis itself if the thickened segment is beyond the short segment of luminal narrowing. In that situation, we presumed that verification of the relationship between the extent of segmental GB wall thickening and the presence of stones could support the idea of segmental thickening of the GB originating from stone formation and subsequent chronic mucosal irritation. Because we found larger stones in segmental adenomyomatosis with diffuse mural thickening of the entire fundal compartment (type C) compared with the smaller stones in patients showing only a limited extent of mural thickening (type A or B), we can suggest a connection between chronic inflammation and the long-standing lithogenic condition.

There are several limitations to the present study. As mentioned above, histopathological verification of the presence and extent of segmental adenomyomatosis could not be performed in most cases, even in patients treated by cholecystectomy. Although the pathogenesis and pathologic findings of chronic cholecystitis and segmental adenomyomatosis are different, they can be difficult to differentiate solely by imaging findings. Based on the results of this study, which showed a high prevalence of type C segmental adenomyomatosis in patients with larger stones, we suggest that diffuse mural thickening of the entire fundal compartment originates from secondary inflammation rather than from the Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses throughout the entire wall. Due to the lack of pathology details, however, there remains another possibility - that fundal adenomyomatosis combined with type B segmental adenomyomatosis can be regarded as type C depending on the extent of Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses in the fundal portion. Second, ultrasonography (US) findings for the GB were not taken into consideration in this study. Considering that US is one of the most useful modalities in evaluating the GB (17), especially in patients with cholecystolithiasis, it would have been helpful if we had correlated US findings of segmental adenomyomatosis with the CT findings. Furthermore, since segmental adenomyomatosis can be combined with radiolucent stones other than calcified stones, the total prevalence of cholecystolithiasis could not be estimated. Considering these factors, the results presented here could therefore be strengthened by a future study with larger groups of patients with supplementary US findings.

In conclusion, the higher prevalence of stones compared to the neck compartment, CT features showing a wide extent of mural thickening and large stones in the fundal compartment suggest a contribution of segmental adenomyomatosis to stone formation and chronic inflammation.

Figures and Tables

| Fig. 1Schematic drawing of the different types of segmental adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder.A. Type A represents a mural thickening limited to the narrow segment.

B. Type B represents a mural thickening partially extended in the fundal direction

C. Type C represents a mural thickening involving the entire fundal compartment of the gallbladder.

|

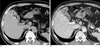

| Fig. 2A 64-year-old man with segmental adenomyomatosis with a calcified GB stone and mural thickening involving the entire fundal compartment (type C).A. This precontrast axial CT image shows focal luminal narrowing of GB (arrow) with a 1.8 cm calcified stone in the fundal compartment (arrowheads).

B. Post-contrast axial CT image showing a diffusely thickened wall with abnormal contrast enhancement including the entire fundal compartment (arrowheads) and the narrowing segment (arrow).

|

| Fig. 3A 31-year-old man with segmental adenomyomatosis with multiple calcified sandy stones in the fundal compartment and mural thickening partially extended in the fundal direction (type B).A. Precontrast axial CT image showing innumerable calcified sandy stones (arrow) in the fundal portion of the GB.

B, C. Post-contrast axial (B) and coronal (C) CT images showing segmental luminal narrowing (arrow) and mural thickening partially extended in the fundal direction (arrowheads).

|

| Fig. 4A 40-year-old woman with segmental adenomyomatosis without cholecystolithiasis showing the mural thickening limited to the narrowing segment (type A).A. This postcontrast axial CT image shows an en face view of the circumferentially thickened wall with luminal narrowing (arrow) at the body portion of the GB.

B. Post-contrast coronal CT image showing segmental luminal narrowing (arrow) with no abnormal mural thickening in the remaining GB wall and no intraluminal calcified stone density.

|

References

1. Colquhoun J. Adenomyomatosis of the gall-bladder (intramural diverticulosis). Br J Radiol. 1961; 34:101–112.

2. Jutras JA. Hyperplastic cholecystoses; Hickey lecture, 1960. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1960; 83:795–827.

3. Kasahara Y, Sonobe N, Tomiyoshi H, Imano M, Nakatani M, Urata T, et al. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: a clinical survey of 30 surgically treated patients. Nippon Geka Hokan. 1992; 61:190–198.

4. Tanno S, Obara T, Maguchi H, Fujii T, Mizukami Y, Shudo R, et al. Association between anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union and adenomyomatosis of the gall-bladder. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998; 13:175–180.

5. Kurihara K, Mizuseki K, Ninomiya T, Shoji I, Kajiwara S. Carcinoma of the gall-bladder arising in adenomyomatosis. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1993; 43:82–85.

6. Nishimura A, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Segmental adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder predisposes to cholecystolithiasis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004; 11:342–347.

7. Ootani T, Shirai Y, Tsukada K, Muto T. Relationship between gallbladder carcinoma and the segmental type of adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. Cancer. 1992; 69:2647–2652.

8. Klose KC, Persigehl M, Biesterfeld S, Gunther RW. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder in CT. Radiologe. 1991; 31:73–81.

9. Chao C, Hsiao HC, Wu CS, Wang KC. Computed tomographic finding in adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder. J Formos Med Assoc. 1992; 91:467–469.

10. Kim MJ, Oh YT, Park YN, Chung JB, Kim DJ, Chung JJ, et al. Gallbladder adenomyomatosis: findings on MRI. Abdom Imaging. 1999; 24:410–413.

11. Nussle K, Brambs HJ, Rieber A. Adenomyomatosis of the gallbladder: ultrasound findings. Rontgenpraxis. 1998; 51:155–158.

12. Gore RM, Levin MS. Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier;2008. p. 1446–1447.

13. Vilkin A, Nudelman I, Morgenstern S, Geller A, Bar Dayan Y, Levi Z, et al. Gallbladder inflammation is associated with increase in mucin expression and pigmented stone formation. Dig Dis Sci. 2007; 52:1613–1620.

14. Domeyer PJ, Sergentanis TN, Zagouri F, Tzilalis B, Mouzakioti E, Parasi A, et al. Chronic cholecystitis in elderly patients. Correlation of the severity of inflammation with the number and size of the stones. In Vivo. 2008; 22:269–272.

15. Hsing AW, Gao YT, Han TQ, Rashid A, Sakoda LC, Wang BS, et al. Gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a populationbased study in China. Br J Cancer. 2007; 97:1577–1582.

16. Owen CC, Bilhartz LE. Gallbladder polyps, cholesterolosis, adenomyomatosis, and acute acalculous cholecystitis. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2003; 14:178–188.

17. Yang HL, Li ZZ, Sun YG. Reliability of ultrasonography in diagnosis of biliary lithiasis. Chin Med J (Engl). 1990; 103:638–641.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download