Abstract

Hyperglycemia during chemotherapy occurs in approximately 10% to 30% of patients. Glucocorticoids and L-asparaginase are well known to cause acute hyperglycemia during chemotherapy. Long-term hyperglycemia is also frequently observed, especially in patients with hematologic malignancies treated with L-asparaginase-based regimens and total body irradiation. Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia often develops because of increased insulin resistance, diminished insulin secretion, and exaggerated hepatic glucose output. Screening strategies for this condition include random glucose testing, hemoglobin A1c testing, oral glucose loading, and fasting plasma glucose screens. The management of hyperglycemia starts with insulin or sulfonylurea, depending on the type, dose, and delivery of the glucocorticoid formulation. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors are associated with a high incidence of hyperglycemia, ranging from 13% to 50%. Immunotherapy, such as anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibody treatment, induces hyperglycemia with a prevalence of 0.1%. The proposed mechanism of immunotherapy-induced hyperglycemia is an autoimmune process (insulitis). Withdrawal of the PD-1 inhibitor is the primary treatment for severe hyperglycemia. The efficacy of glucocorticoid therapy is not fully established and the decision to resume PD-1 inhibitor therapy depends on the severity of the hyperglycemia. Diabetic patients should achieve optimized glycemic control before initiating treatment, and glucose levels should be monitored periodically in patients initiating mTOR inhibitor or PD-1 inhibitor therapy. With regard to hyperglycemia caused by anti-cancer therapy, frequent monitoring and proper management are important for promoting the efficacy of anti-cancer therapy and improving patients' quality of life.

Diabetes mellitus is associated with substantial premature death from several causes, including cancers, infectious diseases, external causes, intentional self-harm, and degenerative disorders, independently of several major risk factors. In particular, the prognosis of cancers originating from various organs has been found to be closely related with the degree of hyperglycemia. The cancer-specific death rate tends to rise with mean fasting glucose levels [1]. Cancer patients often die from infections, organ failure, vascular events, or carcinomatosis [2]. Acute hyperglycemia causes a wide range of adverse effects, such as endothelial dysfunction and the uncontrolled influx of glucose into insulin-independent cells, which leads to increased levels of reactive oxygen species and cellular cascades. Elevated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) has also been found to be associated with the aggressiveness of tumors and the survival of patients with colorectal cancer [3], prostate cancer [4], and endometrial cancer [5]. Intensive glycemic control has been found to reduce the risk of infection [6] and cancer-specific mortality [78910].

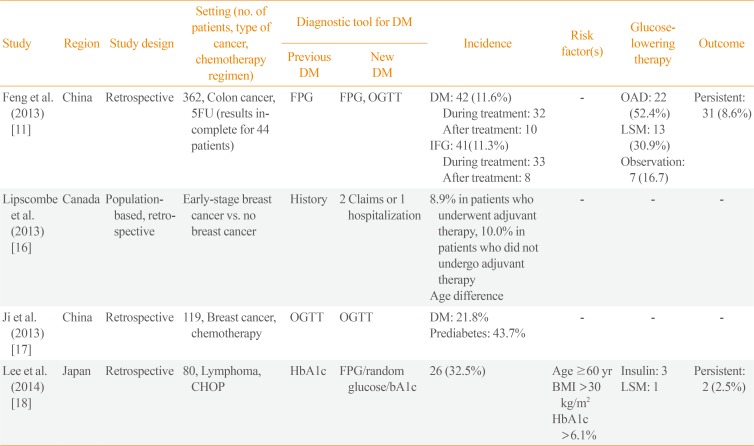

Hyperglycemia can arise from various causes in cancer patients. The results from previous studies regarding chemotherapy induced hyperglycemia were summarized in Table 1. First, cancer and diabetes mellitus share common risk factors: older age, male sex, obesity, lack of physical activity, a high-calorie diet, and tobacco smoking. In a meta-analysis of 23 population- and clinic-based observational studies, the risk of cancer had an overall hazard ratio of 1.41 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.28 to 1.55) for all cancer types in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients compared with normoglycemic patients. Secondly, acute stresses experienced during cancer treatment, potentially by the chemotherapeutic agents themselves, exacerbate insulin resistance, which leads to hyperglycemia.

During cytotoxic chemotherapy, acute hyperglycemia happens frequently and transiently. Diabetes and impaired fasting glucose were found to occur in 11.6% and 11.3% of patients with colorectal cancer during chemotherapy, respectively. Among 42 diabetic patients, six (14%) were treated using an insulin-based regimen, six (14%) by sulfonylurea and acarbose or metformin, and 10 (24%) by acarbose or metformin alone. Diet control alone was applied to 13 patients (31%), and hyperglycemia was spontaneously remitted in seven patients (17%). Intravenous glucocorticoids were administered in 14 of the 42 diabetes patients (33.3%), with a median accumulated dose of 47.5 mg (12.5 mg per cycle) [11].

L-asparaginase, a cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agent, can induce hyperglycemia through both direct and indirect effects. A direct toxic effect is exerted on pancreatic β-cells via the inhibition of insulin production and release. The indirect contribution of L-asparaginase to hyperglycemia is related to the induction of pancreatitis. Impaired β-cell function can persist even after the termination of chemotherapy [12]. In a study of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, 32 children who had a normal weight, no familial history of diabetes mellitus, and no history of hyperglycemia during chemotherapy (off therapy for at least 1 year) were evaluated for β-cell function. Intravenous and oral glucose tolerance testing detected 22 patients (69%) with an impaired first-phase insulin response, nine patients with impaired glucose tolerance, and one patient with overt diabetes. Children with an impaired insulin response showed reduced β-cell function after glucose loading, but their insulin resistance did not differ.

The long-term effect of chemotherapy has been explored in childhood cancer survivors. The prevalence of diabetes in cancer survivors has been reported to range from 2.5% (as assessed by history-taking) to 15.6% (as assessed by oral glucose loading). A number of suggestions regarding the underlying mechanisms have been offered: functional damage to pancreatic β-cells, weight gain, insulin resistance, various hormonal deficiencies, damage to non-hormonal systems, changes in lipid metabolism, inflammatory mediators and adipokines, and reduced physical activity [12131415]. The risk factors are total body irradiation (TBI), untreated hypogonadism, and abdominal adiposity (a feature related to cranial radiation therapy). As for TBI, a preparative therapy for bone marrow transplantation, the key role it plays in the genesis of insulin resistance is the alteration of mitochondrial function in the muscle, liver, and pancreas, resulting in the development of insulin resistance and T2DM [14].

In adults, a study of 24,976 postmenopausal breast cancer survivors in the Ontario Cancer Registry showed that the incidence of T2DM was 9.7% during a follow-up period of 5.8 years. In most women, the risk began to increase 2 years after cancer diagnosis. However, the highest risk was in the first 2 years in those who had received adjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy treatment may cause diabetes to develop earlier in susceptible women. Weight gain, estrogen suppression, and glucocorticoids are risk factors [11161718].

Glucocorticoids can also induce insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. The incidence of hyperglycemia (defined as blood glucose >200 mg/dL) in hospitalized patients treated with glucocorticoids without a known history of diabetes is >50%. The odds ratio for developing new-onset diabetes after taking glucocorticoids has been reported to range from 1.36 to 2.31 in various studies. The predictors have been found to be the dose and duration of glucocorticoid treatment; old age; overweight; previous glucose intolerance; reduced sensitivity to insulin or impaired insulin secretion stimulated by glucose; a family history of diabetes; non-white ethnicity; type A30, B27, and Bw42 human leukocyte antigens (HLA); and receiving a kidney transplant from a deceased donor [1920].

The pathophysiology of glucocorticoid-induced diabetes involves an increase in insulin resistance; reduced glucose uptake in muscle and adipose tissue (via insulin-sensitive glucose transporter type 4); catabolism of muscle and adipose tissue, accompanying a rise in free fatty acids and triglycerides; increased glucose production; increased hepatic gluconeogenesis via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α; and direct effects on pancreatic β-cells, including inhibition of the production and secretion of insulin, a proapoptotic effect on β-cells, a reduction in insulin biosynthesis, and β-cell failure. Development of glucocorticoid-induced diabetes depends on the dose and duration of exposure. The short-term use of high-dose intravenous or oral glucocorticoids causes high fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and relatively stable insulin levels, whereas longer exposure to even relatively low doses of glucocorticoids induces high FPG and insulin levels. The greatest glucose excursions occur 6 to 8 hours after glucocorticoid administration. The predisposing factors for glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia have been suggested to be weight gain, ethnicity, female sex, Down syndrome, puberty, and the severity of the disease itself [2122232425].

Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes can be screened for by several methods. The first approach is the measurement of FPG, which is a simple method. However, it underestimates glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia, especially in intermediate-acting glucocorticoid treatment with single morning doses. Second, oral glucose loading testing is the most precise method of detecting hyperglycemia, but is not feasible in the clinical setting. Additionally, it underestimates glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia that occurs predominantly in the evening. Third, HbA1c may be a suitable method for diagnosis in patients treated with glucocorticoids for more than 2 months, but is not useful for recently initiated treatment. Fourth, random plasma glucose levels over 200 mg/dL are a very useful criterion, but have relatively low sensitivity. Fifth, postprandial glucose testing after lunch offers the greatest diagnostic sensitivity. Finally, preprandial glucose testing at dinner offers less sensitivity, but is easier to standardize.

Management should be conducted with due consideration of glycemic variability. Glycemic variability depends on the type, dose, and delivery of the glucocorticoid formulation. Therefore, in patients treated with a once-a-day intermediate-acting glucocorticoid (prednisolone), peak hyperglycemia occurs in approximately 8 hours, and intermediate-acting insulin is the drug of choice. In contrast, for a long-acting glucocorticoid (dexamethasone) or a multidose or continuous glucocorticoid, long-acting insulin is the best choice. If the development of transient hyperglycemia is expected, the ideal anti-diabetic drug would be potent, immediate-acting, and with unlimited hypoglycemic action. Oral anti-diabetic drugs can be applied for mild glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia (glycemia <200 mg/dL), although insulin remains the best choice because of its efficacy and flexibility [262728].

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors may increase total cholesterol, triglyceride, and glucose levels [293031]. Grade 3 to 4 hyperglycemic events occurred in 12% of patients treated with everolimus, and in 11% of patients treated with temsirolimus [3032]. The pathophysiology of mTOR inhibitor-related hyperglycemia involves two aspects. First, the direct effect of mTOR inhibitors on pancreatic β-cells causes a reduction in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and an increase in apoptosis, with detrimental effects on cell viability and proliferation. Second, peripheral insulin resistance has been found to be exaggerated by mTOR inhibitors. In muscle, reduced glucose uptake and a reduction in muscle mass takes place. In the liver, mTOR inhibitors promote gluconeogenesis, while they reduce lipid uptake in adipose tissue [3133].

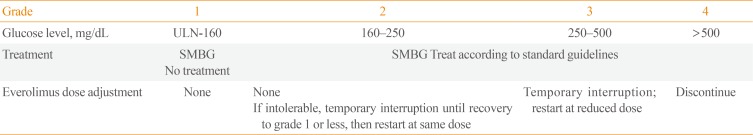

The clinical features of mTOR inhibitor-related hyperglycemia include the fact that approximately half of hyperglycemic events (grade 2 or higher) occur within the first 6 weeks of treatment, and they are transient or resolve prior to the next mTOR inhibitor dose in patients without a history of diabetes. The goal of managing mTOR inhibitor-related hyperglycemia is to preserve the quality of life via the prevention of acute signs (polyuria, nocturia, or polydipsia) and subsequent subacute complications of sustained hyperglycemia such as infections, hypercoagulability, catabolic weight loss, and osmotic diuresis. The targets of glycemic control are (1) FPG <160 mg/dL, (2) random plasma glucose level <200 mg/dL, and (3) HbA1c ≤8% [3133].

Fasting serum glucose should be monitored before initiating and during everolimus treatment. Before initiating treatment, clinicians should optimize glycemic control. During treatment, patients should be advised to report excessive thirst or urinary frequency. The main strategy for glycemic control is dietary modification, as well as adapting the dosage of or initiating insulin and/or hypoglycemic agent therapy (Table 2) [313334].

Immunotherapy to activate cytotoxic T-cells is a novel anti-tumor approach, targeting immune checkpoint molecules, including receptors expressed on T-cell and antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Representative immune checkpoint molecules include receptors expressed on T-cells (programmed death 1 [PD-1]/cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 [CTLA-4]) and APCs (programmed death-ligand 1 [PD-L1]), which have a suppressive effect on the immune response after T-cell or APC interaction. The role of PD-1 and PD-L1 is to maintain tolerance and to downregulate ineffective or detrimental immune responses. Furthermore, they interfere with the initiation of protective immune responses (chronic viral infections, expansion of tumor cells). Therefore, blocking antibodies to PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 induces increased T-cell activation, breaking down tumor immune tolerance following enhanced immunological anti-tumor activity [3536].

Recent clinical trials have shown that antibodies to PD-1 can provide significant benefits for patients with advanced solid tumors. In a recent report, a PD-1 antibody, lambrolizumab, was administered to a total of 135 patients with advanced melanoma [37]. The confirmed response rate was 38% (95% CI, 25% to 44%) and 77% of the patients had a reduction in the tumor burden. Based on this result, the drug was approved in 2014 for the treatment of advanced metastatic melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer. In a phase 1 multicenter trial of an anti-PD-L1 antibody, BMS-936559, several adverse events were reported in 207 patients [38]. The study reported that immunotherapy increased several endocrine disorders, such as hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and autoimmune thyroiditis, with a dose-dependent manner [39]. These findings can be explained as an autoimmune reaction exaggerated by PD-1 targeted therapy, because PD-1 may play critical roles in the regulation of autoimmunity.

The PD-1 protein is expressed in the β-cells of the islets [40]. In an experimental report in which non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice were studied, blockage of PD-1 or PD-L1 rapidly precipitated diabetes in prediabetic female mice regardless of age (from 1 week old to 10 weeks old) [40]. In addition, overexpression of PD-L1 in NOD mice provided a protective effect from diabetes. In the study of lambrolizumab, hyperglycemic events were not reported [37]; however, in patients treated with pembrolizumab after approval, hyperglycemic events were reported in 45% to 49% of patients, and 3% to 6% experienced grade 3 or 4 hyperglycemic events. Among 2,117 patients, fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) occurred with an incidence rate of 0.1% and at various stages of treatment, ranging from 1 week to 12 months [4142].

In a case series of five patients, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibodies were positive in three patients and the susceptible HLAs were HLA A2.1 and DR4 [41]. In one case report, fulminant T1DM occurred 2 weeks after pembrolizumab administration, manifesting as diabetic ketoacidosis with negative anti-GAD and islet antigen-2 antibodies, but undetectable serum C-peptide [43]. In another report, fasting blood glucose levels and total daily insulin requirements began to gradually decline following pembrolizumab discontinuation without any immunosuppressive agents or glucocorticoids [44]. By day 54 after the onset of insulin-dependent diabetes, the patient was able to discontinue insulin.

With the development of new drugs targeting various molecular pathways, novel endocrine disorders occur and pose challenges to endocrinologists. This is especially notable since the number of novel drugs in the field of cancer therapy has soared. Regarding hyperglycemia related to anti-cancer treatments, frequent monitoring and active management should be combined to prevent the adverse events caused by acute hyperglycemia and to promote the efficacy of anti-cancer therapy.

References

1. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, Di Angelantonio E, Gao P, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011; 364:829–841. PMID: 21366474.

2. Inagaki J, Rodriguez V, Bodey GP. Proceedings: causes of death in cancer patients. Cancer. 1974; 33:568–573. PMID: 4591273.

3. Siddiqui AA, Spechler SJ, Huerta S, Dredar S, Little BB, Cryer B. Elevated HbA1c is an independent predictor of aggressive clinical behavior in patients with colorectal cancer: a case-control study. Dig Dis Sci. 2008; 53:2486–2494. PMID: 18409001.

4. Hong SK, Lee ST, Kim SS, Min KE, Byun SS, Cho SY, et al. Significance of preoperative HbA1c level in patients with diabetes mellitus and clinically localized prostate cancer. Prostate. 2009; 69:820–826. PMID: 19189299.

5. Stevens EE, Yu S, Van Sise M, Pradhan TS, Lee V, Pearl ML, et al. Hemoglobin A1c and the relationship to stage and grade of endometrial cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012; 286:1507–1512. PMID: 22797661.

6. Murad MH, Coburn JA, Coto-Yglesias F, Dzyubak S, Hazem A, Lane MA, et al. Glycemic control in non-critically ill hospitalized patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97:49–58. PMID: 22090269.

7. Erickson K, Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Heath DD, et al. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:54–60. PMID: 21115861.

8. Peairs KS, Barone BB, Snyder CF, Yeh HC, Stein KB, Derr RL, et al. Diabetes mellitus and breast cancer outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29:40–46. PMID: 21115865.

9. Derr RL, Ye X, Islas MU, Desideri S, Saudek CD, Grossman SA. Association between hyperglycemia and survival in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27:1082–1086. PMID: 19139429.

10. Richardson LC, Pollack LA. Therapy insight: influence of type 2 diabetes on the development, treatment and outcomes of cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005; 2:48–53. PMID: 16264856.

11. Feng JP, Yuan XL, Li M, Fang J, Xie T, Zhou Y, et al. Secondary diabetes associated with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy regimens in non-diabetic patients with colorectal cancer: results from a single-centre cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2013; 15:27–33. PMID: 22594556.

12. Mohn A, Di Marzio A, Capanna R, Fioritoni G, Chiarelli F. Persistence of impaired pancreatic beta-cell function in children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2004; 363:127–128. PMID: 14726167.

13. Bizzarri C, Pinto RM, Ciccone S, Brescia LP, Locatelli F, Cappa M. Early and progressive insulin resistance in young, non-obese cancer survivors treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015; 62:1650–1655. PMID: 26017459.

14. Meacham LR, Sklar CA, Li S, Liu Q, Gimpel N, Yasui Y, et al. Diabetes mellitus in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Increased risk associated with radiation therapy: a report for the childhood cancer survivor study. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:1381–1388. PMID: 19667301.

15. de Vathaire F, El-Fayech C, Ben Ayed FF, Haddy N, Guibout C, Winter D, et al. Radiation dose to the pancreas and risk of diabetes mellitus in childhood cancer survivors: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2012; 13:1002–1010. PMID: 22921663.

16. Lipscombe LL, Chan WW, Yun L, Austin PC, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Incidence of diabetes among postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. Diabetologia. 2013; 56:476–483. PMID: 23238788.

17. Ji GY, Jin LB, Wang RJ, Bai Y, Yao ZX, Lu LJ, et al. Incidences of diabetes and prediabetes among female adult breast cancer patients after systemic treatment. Med Oncol. 2013; 30:687. PMID: 23925668.

18. Lee SY, Kurita N, Yokoyama Y, Seki M, Hasegawa Y, Okoshi Y, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus in patients with lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2014; 22:1385–1390. PMID: 24362844.

19. Donihi AC, Raval D, Saul M, Korytkowski MT, DeVita MA. Prevalence and predictors of corticosteroid-related hyperglycemia in hospitalized patients. Endocr Pract. 2006; 12:358–362. PMID: 16901792.

20. Clore JN, Thurby-Hay L. Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. Endocr Pract. 2009; 15:469–474. PMID: 19454391.

21. Knoderer HM, Robarge J, Flockhart DA. Predicting asparaginase-associated pancreatitis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007; 49:634–639. PMID: 16937362.

22. Spinola-Castro AM, Siviero-Miachon AA, Andreoni S, Tosta-Hernandez PD, Macedo CR, Lee ML. Transient hyperglycemia during childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia chemotherapy: an old event revisited. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2009; 7:465–472. PMID: 19701154.

23. Siviero-Miachon AA, Spinola-Castro AM, Guerra-Junior G. Hyperglycemia in cancer survivors: from diagnosis through survivorship. J Metab Syndr. 2014; 3:e109.

24. Baillargeon J, Langevin AM, Mullins J, Ferry RJ Jr, DeAngulo G, Thomas PJ, et al. Transient hyperglycemia in Hispanic children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005; 45:960–963. PMID: 15700246.

25. Kavey RE, Allada V, Daniels SR, Hayman LL, McCrindle BW, Newburger JW, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science; the Councils on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Epidemiology and Prevention, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism, High Blood Pressure Research, Cardiovascular Nursing, and the Kidney in Heart Disease; and the Interdisciplinary Working Group on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2006; 114:2710–2738. PMID: 17130340.

26. Iwamoto T, Kagawa Y, Naito Y, Kuzuhara S, Kojima M. Steroid-induced diabetes mellitus and related risk factors in patients with neurologic diseases. Pharmacotherapy. 2004; 24:508–514. PMID: 15098806.

27. Magee MH, Blum RA, Lates CD, Jusko WJ. Prednisolone pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in relation to sex and race. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001; 41:1180–1194. PMID: 11697751.

28. American Diabetes Association. 14. Diabetes care in the hospital. Diabetes Care. 2017; 40(Suppl 1):S120–S127. PMID: 27979901.

29. Kreis H, Cisterne JM, Land W, Wramner L, Squifflet JP, Abramowicz D, et al. Sirolimus in association with mycophenolate mofetil induction for the prevention of acute graft rejection in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2000; 69:1252–1260. PMID: 10798738.

30. Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008; 372:449–456. PMID: 18653228.

31. Busaidy NL, Farooki A, Dowlati A, Perentesis JP, Dancey JE, Doyle LA, et al. Management of metabolic effects associated with anticancer agents targeting the PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30:2919–2928. PMID: 22778315.

32. Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2271–2281. PMID: 17538086.

33. Aapro M, Andre F, Blackwell K, Calvo E, Jahanzeb M, Papazisis K, et al. Adverse event management in patients with advanced cancer receiving oral everolimus: focus on breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014; 25:763–773. PMID: 24667713.

34. Eisen T, Sternberg CN, Robert C, Mulders P, Pyle L, Zbinden S, et al. Targeted therapies for renal cell carcinoma: review of adverse event management strategies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012; 104:93–113. PMID: 22235142.

35. Drake CG, Lipson EJ, Brahmer JR. Breathing new life into immunotherapy: review of melanoma, lung and kidney cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014; 11:24–37. PMID: 24247168.

36. Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015; 37:764–782. PMID: 25823918.

37. Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013; 369:134–144. PMID: 23724846.

38. Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, et al. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:2455–2465. PMID: 22658128.

39. Pedoeem A, Azoulay-Alfaguter I, Strazza M, Silverman GJ, Mor A. Programmed death-1 pathway in cancer and autoimmunity. Clin Immunol. 2014; 153:145–152. PMID: 24780173.

40. Ansari MJ, Salama AD, Chitnis T, Smith RN, Yagita H, Akiba H, et al. The programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway regulates autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. J Exp Med. 2003; 198:63–69. PMID: 12847137.

41. Hughes J, Vudattu N, Sznol M, Gettinger S, Kluger H, Lupsa B, et al. Precipitation of autoimmune diabetes with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2015; 38:e55–e57. PMID: 25805871.

42. Okamoto M, Okamoto M, Gotoh K, Masaki T, Ozeki Y, Ando H, et al. Fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus with anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy. J Diabetes Investig. 2016; 7:915–918.

43. Gaudy C, Clevy C, Monestier S, Dubois N, Preau Y, Mallet S, et al. Anti-PD1 pembrolizumab can induce exceptional fulminant type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015; 38:e182–e183. PMID: 26310693.

44. Hansen E, Sahasrabudhe D, Sievert L. A case report of insulin-dependent diabetes as immune-related toxicity of pembrolizumab: presentation, management and outcome. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016; 65:765–767. PMID: 27067877.

45. Corsello SM, Barnabei A, Marchetti P, De Vecchis L, Salvatori R, Torino F. Endocrine side effects induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013; 98:1361–1375. PMID: 23471977.

46. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:711–723. PMID: 20525992.

47. Ryder M, Callahan M, Postow MA, Wolchok J, Fagin JA. Endocrine-related adverse events following ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma: a comprehensive retrospective review from a single institution. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014; 21:371–381. PMID: 24610577.

Table 1

Summary of Results from Previous Studies Regarding Chemotherapy-Induced Hyperglycemia

| Study | Region | Study design | Setting (no. of patients, type of cancer, chemotherapy regimen) | Diagnostic tool for DM | Incidence | Risk factor(s) | Glucose-lowering therapy | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous DM | New DM | ||||||||

| Feng et al. (2013) [11] | China | Retrospective | 362, Colon cancer, 5FU (results incomplete for 44 patients) | FPG | FPG, OGTT |

DM: 42 (11.6%) During treatment: 32 After treatment: 10 IFG: 41(11.3%) During treatment: 33 After treatment: 8 |

- |

OAD: 22 (52.4%) LSM: 13 (30.9%) Observation: 7 (16.7) |

Persistent: 31 (8.6%) |

| Lipscombe et al. (2013) [16] | Canada | Population-based, retrospective | Early-stage breast cancer vs. no breast cancer | History | 2 Claims or 1 hospitalization |

8.9% in patients who underwent adjuvant therapy, 10.0% in patients who did not undergo adjuvant therapy Age difference |

- | - | - |

| Ji et al. (2013) [17] | China | Retrospective | 119, Breast cancer, chemotherapy | OGTT | OGTT |

DM: 21.8% Prediabetes: 43.7% |

- | - | - |

| Lee et al. (2014) [18] | Japan | Retrospective | 80, Lymphoma, CHOP | HbA1c | FPG/random glucose/bA1c | 26 (32.5%) |

Age ≥60 yr BMI >30 kg/m2 HbA1c >6.1% |

Insulin: 3 LSM: 1 |

Persistent: 2 (2.5%) |

DM, diabetes mellitus; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; LSM, life style modification; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2

Recommendations for the Clinical Management of Hyperglycemic Events by Symptom Severity [31]

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download