Abstract

Background

When patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) are first referred to a hospital from primary health care clinics, physicians have to decide whether to administer an oral hypoglycemic agent (OHA) immediately or postpone a medication change in favor of diabetes education regarding diet or exercise. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of diabetes education alone (without alterations in diabetes medication) on blood glucose levels.

Methods

The study was conducted between January 2009 and December 2013 and included patients with DM. The glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels were evaluated at the first visit and after 3 months. During the first medical examination, a designated doctor also conducted a diabetes education session that mainly covered dietary management.

Results

Patients were divided into those who received no diabetic medications (n=66) and those who received an OHA (n=124). Education resulted in a marked decrease in HbA1c levels in the OHA group among patients who had DM for <1 year (from 7.0%±1.3% to 6.6%±0.9%, P=0.0092) and for 1 to 5 years (from 7.5%±1.8% to 6.9%±1.1%, P=0.0091). Those with DM >10 years showed a slightly lower HbA1c target achievement rate of <6.5% (odds ratio, 0.089; P=0.0024).

Conclusion

For patients who had DM for more than 5 years, higher doses or changes in medication were more effective than intensive active education. Therefore, individualized and customized education are needed for these patients. For patients with a shorter duration of DM, it may be more effective to provide initial intensive education for diabetes before prescribing medicines, such as OHAs.

There are approximately 3.2 million patients with diabetes in Korea, comprising approximately 10% of the adult population [123]. Moreover, this number is predicted to rapidly increase to approximately 6 million by 2050 [3]. Blood glucose levels should be strictly controlled because diabetes is associated with cardiovascular disease [4]. Despite the rapid increase in diabetes mellitus (DM) in the Korean population [56], less than 30% of patients with DM achieve a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of 6.5% or lower. Even with the American Diabetes Association's guidelines of a target HbA1c less than 7.0% as the final goal of controlling blood glucose being applied in Korea, the rate of goal achievement (HbA1c <7%) is still less than 50% [378]. Therefore, most patients with DM are not managing their disease properly. One of the many reasons for the poor management of blood glucose is patients' ignorance regarding blood glucose self-management due to a lack of systematic education.

It is reported that 60.6% of patients have never received any education about DM [9]; another study reported that only 14.6% to 19.2% of patients received education [2]. The importance of DM education is well known [10]; however, the number of patients who actually receive DM education is very small. This deficiency leads to poorly controlled glucose levels, which can cause various complications. However, not all DM education yields good outcomes. The effect of education differs depending on factors such as the patient's age and medication status. Therefore, individualized DM education should be provided.

To implement a more effective, individualized diabetes education program, a study of patient characteristics and education programs based on these characteristics are needed. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of DM education alone without changes in medication on blood glucose levels among patients visiting a hospital for the first time. The purpose of this study was to determine the direct effect of education and emphasize its importance, and the secondary goal was to select effective groups for DM education by analyzing the characteristics of patients in whom education is effective. The study then attempted to classify the group that experienced the greatest effect to prepare an individualized framework for diabetes education.

This study was an electronic medical record (EMR)-based retrospective cohort study. The study was conducted among patients who visited a tertiary teaching hospital for the first time between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. The study focused on patients who visited the department of internal medicine (division of endocrinology and metabolism) for the first time after being diagnosed with DM externally or those who were diagnosed with DM during their first visit to the hospital. We extracted data of patients aged 18 to 80 years whose goal was to manage their blood glucose. The study was only conducted among patients who managed their blood glucose with diabetes education alone without changing their oral hypoglycemic agent (OHA). Patients receiving insulin treatment outside the hospital were excluded, as were those who were started on insulin treatment or were hospitalized after their first medical examination. Patients with gestational DM and those who visited the hospital for a check-up prior to surgery were also excluded. Patients whose medication was initiated after the first medical examination or those whose dosage was changed were also excluded. To maintain the consistency of diabetes education, only one doctor in the department of internal medicine with the most experience in DM was designated for the patient education sessions.

This study evaluated the HbA1c level, blood pressure, height, weight, and DM duration, which were measured during the first medical examination. Data related to DM were reported by one researcher directly by reviewing charts. Because this is an EMR study, it was difficult to find patients who visited the hospital at exactly 3 months. Cases for which there was no visit within 2 to 5 months were excluded from this study. Therefore, the HbA1c levels were determined during the second visit, ranging from 2 to 5 months (average of 3 months) after the individual diabetes education was administered.

During the first medical examination, one designated doctor managing the patients conducted a diabetes education session, mainly on dietary management. The recommended caloric intake was calculated based on the patient's body mass index (BMI; according to their height and weight). The main objectives of education included the individualized limitations of energy intake (considering the patients' age and gender), blood pressure, HbA1c, and any complications. This education was steadily and consistently given each time patients visited the hospital. Patients who were overweight or obese with DM were instructed to reduce their caloric intake and lose weight while maintaining healthy eating habits. The education session also included information on the seriousness of the patient's blood glucose level, importance of self-management, and its necessity depending on their age and sex. Information regarding self-blood glucose tests, importance of exercise, and changes in lifestyle was also included. All patients received diabetes education as it was conducted in the doctor's office.

Because of the anonymity of the data and retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was not required. Coded EMR data were used, and patients' hospital registration numbers were deleted to prevent identification of each patient. The study design was such that the actual patient number cannot be detected by any third party and the patient is completely free from the risk of additional physical harm. The Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea approved this study (KC15RISI0849).

Summary statistics are presented as a number (%) for categorical variables and as the mean±standard deviation, median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the patients' pre- and post-visit HbA1c. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the relationship and to estimate the odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval between covariates, and HbA1c of postvisit patients in the OHA group. Statistical analysis for the trend in HbA1c according to the order of categorical variables was assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test. All of the results were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

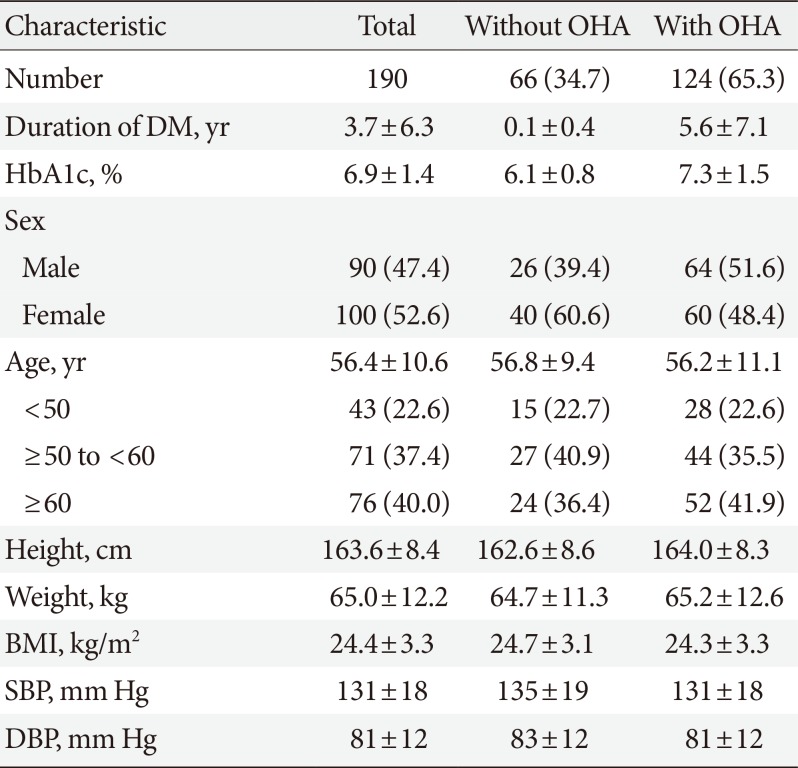

A total of 364 patients revisited the hospital 2 to 5 months after the first examination without being hospitalized. Of these, 174 patients were excluded because their medication was changed. The study was conducted among 66 patients who were not prescribed any diabetic medication and 124 who were prescribed an OHA, for a total of 190 patients (Table 1). There were more female (100/190, 52.6%) than male patients (90/190, 47.4%), and the average patient age was 56.4±10.6 years. The average patient BMI was 24.4±3.3 kg/m2, and most patients were overweight or obese. A total of 66 patients were managing their blood glucose with only lifestyle modifications without medication, and 124 patients were undergoing therapy with OHA.

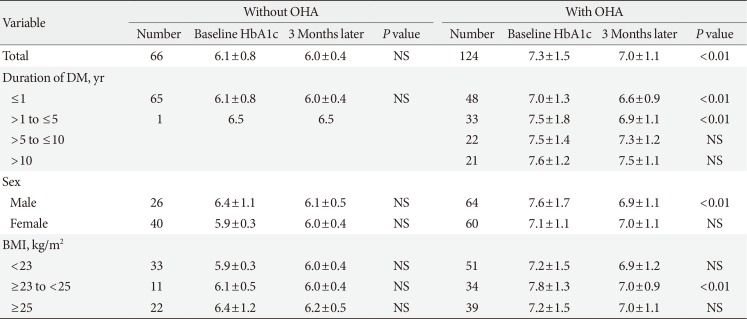

DM education was not effective in patients who visited the hospital for the first time without being prescribed OHA (Table 2). The education tended to be more effective in men (from 6.4±1.1 to 6.1±0.5, P=0.6795) than in women (from 5.9±0.3 to 6.0±0.4, P=0.1829) at an average of 3 months after the individual diabetes education, but this difference was not significant. Patients with BMI under 23 kg/m2 showed a tendency of increased HbA1c (from 5.9±0.3 to 6.0±0.4, P=0.1191), and those with BMI over 25 kg/m2 showed a slight decrease (from 6.4±1.2 to 6.2±0.5, P=0.9690); however, these changes were not significant. In contrast to the non-OHA group, education had a marked effect on the OHA group. Particularly, patients with a DM duration of less than 1 year (from 7.0±1.3 to 6.6±0.9, P=0.0092) and 5 years (from 7.5±1.8 to 6.9±1.1, P=0.0091) showed a significant decrease in HbA1c. Patients with a DM duration of more than 10 years and between 5 to 10 years also showed a slight decrease, but this finding was not significant. Men (from 7.6±1.7 to 6.9±1.1, P<0.0010) showed a larger HbA1c decrease than women (from 7.1±1.1 to 7.0±1.1, P=0.1860), and those with BMI of 23 to 25 kg/m2 showed a significant decrease (from 7.8±1.3 to 7.0±0.9, P<0.0001). Those with BMI less than 23 kg/m2 and over 25 kg/m2 also showed a decrease in HbA1c, but this decrease was not significant. Approximately 11 to 13 months after the first visit, HbA1c was not significantly different from HbA1c at approximately 2 to 5 months except in patients with a DM duration of less than 1 year (data not shown).

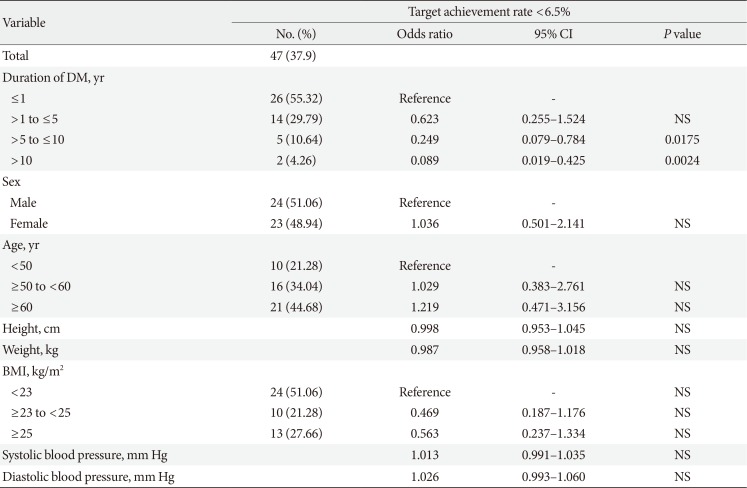

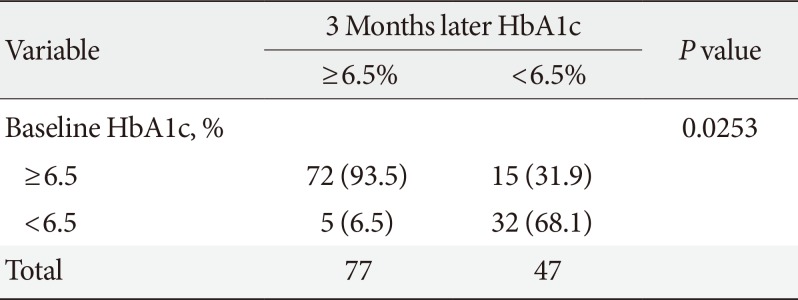

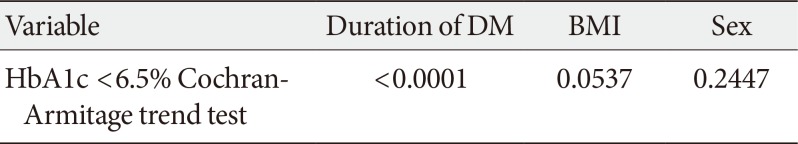

In the OHA group, the HbA1c target achievement rate was 37.9% (Tables 3, 4), with a HbA1c target under 6.5%, and 55.7%, with a HbA1c target under 7.0%. The DM duration had the largest effect on the target achievement rate. A longer DM duration was associated with a lower target achievement rate. Patients with DM for more than 10 years also showed a slightly lower target achievement rate, with a HbA1c target under 6.5% (OR, 0.089; P=0.0024). The sex of the patient appeared to have an effect on the target achievement rate, but this effect was not significant (OR of female patients, 1.036; P=0.9238). Patients older than 60 years of age also tended to show a high target achievement rate (OR, 1.219; P=0.6827), but the difference was not significant. BMI had no significant effect.

The Cochran-Armitage trend test showed that the DM duration had the largest effect on the target achievement rate (Table 5). In other words, the DM duration was associated with both the decrease in HbA1c and target achievement rate. In the case of male patients, the decrease in HbA1c was not very remarkable, but the achievement rate was relatively high. Patients with a BMI of 23 to 25 kg/m2 showed a significant decrease in blood glucose, but BMI did not have a large effect on the target achievement rate.

DM cannot be completely cured and requires strict lifelong blood glucose control as well as self-management. Continuous education for self-management is required to treat and manage chronic complications; however, this education is rarely conducted, and most patients are not aware of how to manage their blood glucose. Moreover, education is not systematically provided by the patient's medical team. It is already well known that knowledge of diabetes and education regarding disease management is more important than medication treatment [11]. A study of diabetes management was conducted in Korea in 2007 and revealed that only 39.4% of patients had undergone one or more education sessions regarding diabetes [7]. In Korea, it is assumed that the lack of a sense of necessity of DM education is the reason for the lack of DM education. It has been reported that patients who received education can manage their blood glucose well and those who have not received education experience consistent increases in HbA1c and subsequent complications [12].

is already well known that blood glucose levels can be improved by DM education and changes in lifestyle habits without prescribing an OHA [131415]. However, some reports indicate that these improvements are not significant [16]. It is assumed that the result may vary depending on the patient's age, baseline HbA1c, and whether the patient uses insulin. Therefore, it is important to study the effect of the education in a specific population group. In this study, the DM duration had a marked effect on both the decrease in HbA1c and target achievement rate. A DM duration greater than 10 years was particularly associated with a smaller HbA1c decrease and target achievement rate. This result is because it was determined that 10 years after a DM diagnosis, there must be at least more than one opportunity for education during that period. Therefore, for tertiary hospital patients with a DM duration of over 5 years, DM education is important if it is their first visit to the hospital to manage blood glucose. However, increasing the dosage or changing medications to further decrease HbA1c and increase the target achievement rate could be even more helpful. However, compared to dosage increases or changes in medications, DM education could be more helpful in patients with a DM duration under 5 years. In a similar study that used a shorter period of diabetes, the awareness of nutrition education was higher and the control of fasting blood glucose and HbA1c was better [17]. Thus, this group showed that nutritional therapy was more effective. However, it was reported that in patients with a long duration of DM, diabetes education did not have an effect on dietary control and blood glucose control. For this reason, in the case of patients with a long duration of illness, the need for individualized meal training methods was emphasized. In the OHA group, baseline HbA1c was higher in men than that in women, but the decrease in HbA1c was also markedly higher in men than that in women after receiving DM education. A male patient with a DM duration of less than 5 years and BMI of 23 to 25 kg/m2 experienced the largest effect of DM education. For female patients with BMI over 25 kg/m2, intensive active education and increasing the dosage or changing the medication would have a greater effect.

Notably, patients over 60 years of age tended to have a high target achievement rate after receiving DM education. The results of this study suggest that it is better to focus on DM education than to change medications in older patients with diabetes. According to research conducted in Korea, patients over 60 years of age showed a higher medication adherence than younger patients [18]. The older the patient [19], the higher the adherence tended to be, indicating that thorough management is required from a young age. Usually, the older patients are, the longer their DM duration would be. Thus, it is important for physicians involved in patient education to provide customized education depending on the patient's age and DM duration. In terms of the consistency of the diabetes education, in particular, lifestyle changes tend to be limited in the educated patients [1112]. Studies have reported that the effect of diabetes education disappears after approximately 6 to 9 months [2021], indicating the importance of consistent education. Despite conflicting results on the effect of the consistency of DM education, they indicate the necessity of post-management and re-education. It is impossible to conduct only education without changing medications in a real clinical situation. It is possible that a proper education in combination with medication changes would yield a better result. Therefore, continuous DM education is needed, especially after the patient is first diagnosed with DM. In this study, medical staff managed blood glucose control according to recommended guidelines. If following the blood glucose management guidelines [22], in the case of a high HbA1c at the first visit, additional or changes in medications should be implemented along with diabetes education. However, in actual clinical practice, there are various cases in which patients refused to add medicines or wanted to add them later. Of course, it is also the role of the medical staff to actively educate or persuade patients to take additional medications in this case. However, there is also the case in which only diabetes education should be implemented without additional medication. In this study, there were no clear criteria for selecting patients who needed additional medicines but only received diabetes education without further prescription. Rather, according to a direct chart review, as mentioned above, most of the patients rejected additional prescriptions or wanted to delay starting them. Based on these results, when patients taking diabetic medications within 5 years after their diabetes diagnosis refused to add medication, more intensive education or persuasion regarding diabetes treatment would be helpful. Conversely, if patients who have been diagnosed with diabetes for more than 5 years refuse to add medication, it would be better to emphasize the benefits of the addition of medicines along with education. Of course, to generalize the results of this study, large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are required. The biggest advantage of an EMR study is that it can acquire a large amount of data for a short period of time before informing RCTs, and the results of which can be seen at a glance, thereby guiding the direction of the study based on the real clinical situation.

However, this study also has several limitations due to the characteristics of an EMR-based retrospective cohort study. First, this study assessed the effect of diabetes education conducted after patients visited the tertiary hospital, but patients with a DM duration of more than 10 years could have received education at least once outside the hospital. Second, some data were omitted, such as height or weight information, as the study was conducted using EMR data. Thus, the study did not investigate other factors that could affect diabetes education. In particular, because EMR data does not include whether patients received diabetes education and socioeconomic factors, such as the education and household income levels, such influences were not reflected in the EMR data. Finally, the baseline HbA1c of the group that did not take medication was only 6.1%, which was unexpected, because better results were found with the patients taking medication. A comparison with a control group without diabetes education would have been more accurate, but there was no control group in this study. However, there was no additional administration or changes in diabetes medications, so if diabetes education was not given, there could have been ethical issues. Therefore, setting a control group for this study was a challenge.

The results of a previous study suggested that patients' compliance after receiving education depends on the quality of the conversation between the medical team and patient at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [2324]. A year-long study [25] in which diabetes education was conducted among T2DM patients in 10 countries showed a significant improvement in both blood glucose control and weight loss. The patient group that received DM education spent less money on treatment, and the gap between those who did and did not receive education increased with time. In particular, the quality of education between the medical team and patient affected the patients' self-care and well-being. This finding indicates that proper education can help the patient accept and manage the disease effectively from an early stage. To accomplish this goal, individualized and customized education is needed. Additional changes, such as social recognition of the importance of DM education and insurance coverage for this education, are needed for patients to receive proper education. The education should be conducted consistently, supporting patients in their self-care. This study aims to provide a foundation to reduce chronic complications and medical expenses through the effect of DM education. These objectives are especially necessary in Korea, where a doctor meets many patients in a limited amount of time, and the government should therefore aim to provide the educator with systematic and standardized materials for high quality education. Economic analysis of the effects of DM education should be performed in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The statistical consultation was supported by a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI14C1731).

References

1. Kim SG, Choi DS. The present state of diabetes mellitus in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2008; 51:791–798.

2. Kim DJ. Epidemiology and current management status of diabetes mellitus in Korea. In : Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Diabetes and Metabolism; 2012 Nov 8-10; Seoul, Korea. Seoul: Korea Diabetes Association;2012. p. 86–87.

3. Korean Diabetes Association. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2012. Seoul: Korean Diabetes Association;2012.

4. Shin JH, Kang JI, Jung Y, Choi YM, Park HJ, So JH, Kim JH, Kim SY, Bae HY. Hemoglobin a1c is positively correlated with framingham risk score in older, apparently healthy nondiabetic korean adults. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2013; 28:103–109. PMID: 24396663.

5. Ha KH, Kim DJ. Trends in the diabetes epidemic in Korea. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2015; 30:142–146. PMID: 26194073.

7. Park SW, Kim DJ, Min KW, Baik SH, Choi KM, Park IB, Park JH, Son HS, Ahn CW, Oh JY, Lee J, Chung CH, Kim J, Kim H. Current status of diabetes management in Korea using National Health Insurance Database. J Korean Diabetes Assoc. 2007; 31:362–367.

8. Jung JH, Lee JH, Noh JW, Park JE, Kim HS, Yoo JW, Song BR, Lee JR, Hong MH, Jang HM, Na Y, Lee HJ, Lee JM, Kang YG, Kim SY, Sim KH. Current status of management in type 2 diabetes mellitus at general hospitals in South Korea. Diabetes Metab J. 2015; 39:307–315. PMID: 26301192.

9. Task Force Team for Basic Statistical Study of Korean Diabetes Mellitus of Korean Diabetes Association. Park IB, Kim J, Kim DJ, Chung CH, Oh JY, Park SW, Lee J, Choi KM, Min KW, Park JH, Son HS, Ahn CW, Kim H, Lee S, Lee IB, Choi I, Baik SH. Diabetes epidemics in Korea: reappraise nationwide survey of diabetes “diabetes in Korea 2007”. Diabetes Metab J. 2013; 37:233–239. PMID: 23991400.

10. Yong YM, Shin KM, Lee KM, Cho JY, Ko SH, Yoon MH, Kim TW, Jeong JH, Park YM, Ko SH, Ahn YB. Intensive individualized reinforcement education is important for the prevention of hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2015; 39:154–163. PMID: 25922810.

11. Ko SH, Song KH, Kim SR, Lee JM, Kim JS, Shin JH, Cho YK, Park YM, Jeong JH, Yoon KH, Cha BY, Son HY, Ahn YB. Long-term effects of a structured intensive diabetes education programme (SIDEP) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 4-year follow-up study. Diabet Med. 2007; 24:55–62. PMID: 17227325.

12. Kim JH, Chang SA. Effect of diabetes education program on glycemic control and self management for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Korean Diabetes J. 2009; 33:518–525.

13. Gagliardino JJ, Aschner P, Baik SH, Chan J, Chantelot JM, Ilkova H, Ramachandran A. DMPS investigators. Patients’ education, and its impact on care outcomes, resource consumption and working conditions: data from the International Diabetes Management Practices Study (IDMPS). Diabetes Metab. 2012; 38:128–134. PMID: 22019715.

14. Duncan I, Ahmed T, Li QE, Stetson B, Ruggiero L, Burton K, Rosenthal D, Fitzner K. Assessing the value of the diabetes educator. Diabetes Educ. 2011; 37:638–657. PMID: 21878591.

15. Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Selfmanagement education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a metaanalysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2002; 25:1159–1171. PMID: 12087014.

16. Hong MH, Yoo JW, Gu MO, Kim SA, Lee JR, Gu MJ, Kang YG, Jang SH, Park BS, Sim KH, Ro SS, Song BR, Eum JH. A study on effects and their continuity of the self regulation education program in patients with type 2 diabetes. Korean Clin Diabetes. 2009; 10:187–195.

17. Woo YJ, Lee HS, Kim WY. Individual diabetes nutrition education can help management for type II diabetes. Korean J Nutr. 2006; 39:641–648.

18. Lee JA, Park KM, Sunwoo S, Yang YJ, Seo YS, Song SW, Kim BS, Kim YS. Factors associated with compliance using diamicron in patients with type 2 diabetes. Korean J Health Promot. 2012; 12:75–82.

19. Kim GY, Park JY, Kim BW. Short-term glycemic control and the related factors in association with compliance in diabetic patients. Korean J Prev Med. 2000; 33:349–363.

20. Svoren BM, Butler D, Levine BS, Anderson BJ, Laffel LM. Reducing acute adverse outcomes in youths with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2003; 112:914–922. PMID: 14523186.

21. Kang MJ, Gu MJ, Kim JY, Park HY, Kim JH, Lee SH, Yoon I, Lim HH, Lee YA, Shin CH, Yang SW. Short-term effect of the diabetes education program in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Korean Soc Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010; 15:164–171.

22. American Diabetes Association. (7) Approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2015; 38(Suppl):S41–S48. PMID: 25537707.

23. Polonsky WH, Belton A, Down S, Capehorn M, Alzaid A, Gamerman V, Nagel F, Lee J, Edelma S. Physician-patient communication at type 2 diabetes diagnosis and its links to physician empathy and patient outcomes: new results from the global IntroDiaTM study (Poster A-15-449). Poster presented at: 51st Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2015. 2015 Sep 14-18; Stockholm, Sweden.

24. Edelman S, Capehorn M, Belton A, Down S, Alzaid A, Gamerman V, Nagel F, Lee J, Polonsky WH. Physician-patient communication at prescription of an additional oral agent for type 2 diabetes: link between conversation elements, physician empathy and patient outcomes (Poster A-15-496) Poster presented at: 51st Meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) 2015. 2015 Sep 14-18; Stockholm, Sweden.

25. Gagliardino JJ, Etchegoyen G. PENDID-LA Research Group. A model educational program for people with type 2 diabetes: a cooperative Latin American implementation study (PEDNID-LA). Diabetes Care. 2001; 24:1001–1007. PMID: 11375360.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of patients

Table 2

The difference between baseline HbA1c and follow-up HbA1c

Table 3

Target achievement rate (HbA1c <6.5%) at 3 months after the individual diabetes education in the oral hypoglycemic agent group

Table 4

The difference between the baseline target achievement rate and follow-up target achievement rate in the oral hypoglycemic agent group

| Variable | 3 Months later HbA1c | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥6.5% | <6.5% | ||

| Baseline HbA1c, % | 0.0253 | ||

| ≥6.5 | 72 (93.5) | 15 (31.9) | |

| <6.5 | 5 (6.5) | 32 (68.1) | |

| Total | 77 | 47 | |

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download