Abstract

Background

We performed the study to examine the impact of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) criterion on the screening of increased risk for diabetes among health check-up subjects in Korea.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed clinical and laboratory data of 37,754 Korean adults (age, 20 to 89 years; 41% women) which were measured during regular health check-ups. After excluding subjects with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus (n=1,812) and with overt anemia (n=318), 35,624 subjects (21,201 men and 14,423 women) were included in the analysis.

Results

Among the 35,624 subjects, 11,316 (31.8%) subjects were categorized as increased risk for diabetes (IRD) by fasting plasma glucose (FPG) criteria, 6,531 (18.1%) subjects by HbA1c criteria, and 13,556 (38.1%) subjects by combined criteria. Therefore, although HbA1c criteria alone identifies 42% [(11,316-6,531)/11,316] fewer subjects with IRD than does FPG criteria, about 20% [(13,556-11,316)/11,316] more subjects could be detected by including new HbA1c criteria in addition to FPG criteria. Among the 13,556 subjects with IRD, 7,025 (51.8%) met FPG criteria only, 2,240 (16.5%) met HbA1c criteria only, and 4,291 (31.7%) met both criteria. Among subjects with impaired fasting glucose, 65% were normal, 32% were IRD, and 3% were diabetes by HbA1c criterion. In receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, cutoff point of HbA1c with optimal sensitivity and specificity for identifying IRD was 5.4%.

The high economical burden and healthy implications of diabetes has led to increasing attempts to prevent its development. Interventions for subjects with 'pre-diabetes' or 'increased risk for diabetes' have been major focus for these prevention efforts. Therefore, identification of these subjects should be effective and reasonable.

When American Diabetes Association (ADA) included the use of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) to diagnose diabetes mellitus with a cut point of ≥6.5% [1] and included this criteria in 2010 guidelines, the ADA also stressed the continuum of risk for diabetes with all glycemic measures and did not formally identify an equivalent intermediate category for HbA1c. The group did note that those with HbA1c levels above the laboratory 'normal' range but below the diagnostic cut point for diabetes (5.7% to 6.4%) are at 'increased risk for diabetes' [1].

However, epidemiological studies [2,3] have shown significant discordance between HbA1c and glucose-based tests for defining high risk for diabetes. Moreover, the degree of diagnostic agreement of HbA1c criteria with the fasting glucose-based criteria may be different across ethnic groups and populations [4-6].

The aim of this study was to examine the differences in prevalence of using fasting plasma glucose (FPG) criteria and HbA1c criteria in defining the increased risk for diabetes (IRD) in Korean asymptomatic health check-up recipients. In addition, we analyzed the concordance between FPG criteria and HbA1c criteria and the sensitivities and specificities of many HbA1c cutoff points.

We retrospectively analyzed clinical and laboratory data of 37,754 Korean adults (age, 20 to 89 years; 41% women) which were recorded during regular health check-ups. After excluding subjects with previously diagnosed diabetes mellitus (n=1,812) and with overt anemia (hemoglobin concentration <12 g/dL) (n=318), 35,624 subjects (21,201 men and 14,423 women) were categorized. IRD was defined by FPG (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L), HbA1c (5.7% to 6.4%), and combined criteria (FPG, 5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L or HbA1c, 5.7% to 6.4%).

Height and weight were measured with subjects wearing light clothing without shoes. Blood pressure was measured with an electric sphygmomanometer on the right arm with subjects in a sitting position after a 5-minute rest. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Blood samples were obtained in the morning after an overnight fast. Plasma glucose was measured by the hexokinase method using an autoanalyzer (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan). Standard liver function testing, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides were also measured using an autoanalyzer (Toshiba). HbA1c was measured with ion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography using an automated analyzer (Variant II™; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Serum insulin concentrations were obtained employing an immunoradiometric assay (TFB, Tokyo, Japan).

Data are expressed as means±standard deviation. χ2 tests were used to compare groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for HbA1c were plotted. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 14.0 for Windows software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

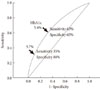

The clinical characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. Among the 35,624 subjects without known diabetes, 11,316 (31.8%) subjects were IRD by FPG criteria, 6,531 (18.1%) by HbA1c criteria, and 13,556 (38.1%) by combined criteria (Fig. 1). Therefore, although HbA1c criteria alone identifies 42% [(11,316-6,531)/11,316] fewer subjects with IRD than does FPG criteria, about 20% [(13,556-11,316)/11,316] more could be detected as IRD by including new HbA1c criteria in addition to FPG criteria. Among the 13,556 subjects with newly detected IRD, 7,025 (51.8%) met FPG criteria only (IRD-FPG group), 2,240 (16.5%) met HbA1c criteria only (IRD-A1c group), and 4,291 (31.7%) met both criteria (Fig. 1). This trend was similar across all age groups, although the prevalences of IRD were getting higher with increasing age (Fig. 2). Among subjects with pre-diabetes by FPG criterion (i.e., impaired fasting glucose), 65% were normal, 32% were IRD, and 3% were diabetes by HbA1c criterion (Fig. 3). Sensitivity and specificity of different HbA1c cutoff points for FPG-based pre-diabetes (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) are shown in Table 2. The optimal cutoff point of HbA1c for IRD in reference to classical FPG-based pre-diabetes was 5.4%, with sensitivity and specificity of 63% and 65%, respectively (Fig. 4).

Our results confirmed that there was a significant discordance in diagnosing subjects with IRD between the FPG- and HbA1c-based criteria. The prevalence of pre-diabetes was about 32% by FPG criteria, 18% by HbA1c criteria, and 38% by combining both criteria. Only 12% met both criteria, and concordance rate between the two criteria was only about 31%. HbA1c criterion has lower sensitivity in detecting subject with IRD compared with FPG criteria, but introducing this new criterion could identify additional 20% of subjects with IRD.

Our results are consistent with previous reports in other populations that showed HbA1c criteria resulted in substantially lower prevalences of being at high risk for diabetes, than prevalences estimated from FPG or oral glucose tolerance test. For example, analyses of the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999-2006) data indicate that the prevalence of pre-diabetes among U.S. adults was 28.2% by the fasting glucose criterion and 12.6% by the HbA1c criterion [2]. Only 7.7% of U.S. adults had pre-diabetes according to both definitions.

As shown in this study, introducing additional HbA1c criteria causes increased prevalence of IRD as well as diabetes. This may contribute to prevent or delay progression to diabetes and development of its complications by early lifestyle intervention. However, the stiff increase in prevalence of IRD may cause inadequate management due to shortage of health care resources. In addition, it can cause a large increase of initial health care cost (although not in long-term [7]), and unnecessary psychological stress for some subjects categorized as IRD.

In this study, additional detection rate of IRD by HbA1c increased with age. This trend has also been observed in previous studies in other populations since HbA1c levels tend to increase with age [8]. Moreover, postchallenge glucose concentrations rise significantly with increasing age even in subjects with normal glucose tolerance [9]. However, it is not practical to set different criteria according to age. Preparation of different guidelines according to age groups and combined other risk factors may be more practical. Prospective studies are needed to define the high risk group in which intensive screening and early intervention will be most beneficial.

The optimal cutoff point of HbA1c in reference to FPG-based pre-diabetes was 5.4% in our study population, which is lower than the ADA-recommended cutoff value. In the International Expert Committee [10] 2009 report, the group did not recommend classification of pre-diabetes, but noted that those with HbA1c levels 6.0% to <6.5% are at high risk of developing diabetes. However, the 6.0% to 6.5% range fails to identify a substantial number of patients who have IFG and/or IGT [1]. Prospective studies indicate that people within the HbA1c range of 5.5% to 6.0% have a 5-year cumulative incidence of diabetes three- to eight-fold higher than incidence in the general population [11-13]. The ADA chose the HbA1c cut-point of 5.7% as it is less sensitive but more specific and has a higher positive predictive value to identify people at risk for later development of diabetes [1]. However, they noted that FPG of 100 mg/dL corresponds to an HbA1c of 5.4% by linear regression analysis among the non-diabetic adult population. The optimal cut-off point of HbA1c 5.4% for IFG obtained by ROC curve analysis of our data coincided well with that.

There have been several reports that compared HbA1c-based criteria with glucose-based criteria for diabetes in Koreans [14-18]. However, little data are available about the validity and usefulness HbA1c criteria for detecting pre-diabetes in Koreans. An hospital-based study in high-risk group [16] showed that 76% of subjects with IFG or IGT had HbA1c ≥5.7%, which is much higher than the 35% sensitivity for the same HbA1c cutoff value in our data. In another study examined 2,045 non-diabetic health check-up recipients, the cut-off value of baseline HbA1c predicting 4-year risk of developing diabetes was 5.35% [17], which is very close to our cut-off value (5.4%) for identifying pre-diabetes in ROC analysis.

There are several limitations in our study. First, our study subjects were not a random sample of the general population. Therefore, we could not estimate the prevalence of IRD in Korean general population. The second limitation of our study is that no information for hemoglobinopathy was available in our data. However, the prevalence of hemoglobinopathy is very low in Korea, and thus the hemoglobin abnormalities may have hardly influenced on the present results. In addition, we excluded all subjects with anemia regardless of its cause, since previous studies suggest that iron deficiency anemia also affects the HbA1c levels [19,20].

In conclusion, although HbA1c criteria alone identifies fewer subjects with pre-diabetes than does FPG criteria, about 20% more could be detected as IRD by inclusion of HbA1c criteria in addition to FPG criteria. Addition of new HbA1c criteria may be useful in detecting the subjects with IRD, but may also cause increase of initial cost for health care and psycho-social burden. Further studies are needed to establish optimal HbA1c cutoff point, and guidelines for screening and management in general population.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Discordance of newly detected increased risk for diabetes (IRD) as assessed during health check-ups according to fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and HbA1c criteria. FPG criteria, FPG (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L); HbA1c criteria, HbA1c (5.7% to 6.4%); combined criteria, FPG (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) or HbA1c (5.7% to 6.4%).

Fig. 2

Prevalence of newly detected increased risk for diabetes in different age groups by fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and HbA1c criteria. FPG criteria, FPG (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L); HbA1c criteria, HbA1c (5.7% to 6.4%); combined criteria, FPG (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) or HbA1c (5.7% to 6.4%).

Fig. 3

Comparison of glycemic status categorized by fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and HbA1c criteria (FPG criteria: normal <5.6 mmol/L, pre-diabetes 5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L, diabetes ≥7.0 mmol/L; HbA1c criteria: normal <5.7%, increased risk for diabetes 5.7% to 6.4%, diabetes ≥6.5%).

Fig. 4

Receiver operating characteristic curves for HbA1c cutoff point for increased risk of diabetes in reference to fasting plasma glucose-based pre-diabetes (impaired fasting glucose).

References

1. American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010. 33:Suppl 1. S62–S69.

2. Mann DM, Carson AP, Shimbo D, Fonseca V, Fox CS, Muntner P. Impact of A1C screening criterion on the diagnosis of pre-diabetes among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2010. 33:2190–2195.

3. Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, Gregg EW, Ford ES, Geiss LS, Bainbridge KE, Fradkin JE. Prevalence of diabetes and high risk for diabetes using A1C criteria in the U.S. population in 1988-2006. Diabetes Care. 2010. 33:562–568.

4. Herman WH, Ma Y, Uwaifo G, Haffner S, Kahn SE, Horton ES, Lachin JM, Montez MG, Brenneman T, Barrett-Connor E. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Differences in A1C by race and ethnicity among patients with impaired glucose tolerance in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2007. 30:2453–2457.

5. Christensen DL, Witte DR, Kaduka L, Jorgensen ME, Borch-Johnsen K, Mohan V, Shaw JE, Tabak AG, Vistisen D. Moving to an A1C-based diagnosis of diabetes has a different impact on prevalence in different ethnic groups. Diabetes Care. 2010. 33:580–582.

6. Likhari T, Gama R. Glycaemia-independent ethnic differences in HbA(1c) in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabet Med. 2009. 26:1068–1069.

7. Saha S, Gerdtham UG, Johansson P. Economic evaluation of lifestyle interventions for preventing diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010. 7:3150–3195.

8. Pani LN, Korenda L, Meigs JB, Driver C, Chamany S, Fox CS, Sullivan L, D'Agostino RB, Nathan DM. Effect of aging on A1C levels in individuals without diabetes: evidence from the Framingham Offspring Study and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2004. Diabetes Care. 2008. 31:1991–1996.

9. Rhee MK, Ziemer DC, Kolm P, Phillips LS. Postchallenge glucose rises with increasing age even when glucose tolerance is normal. Diabet Med. 2006. 23:1174–1179.

10. International Expert Committee. International Expert Committee report on the role of the A1C assay in the diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009. 32:1327–1334.

11. Edelman D, Olsen MK, Dudley TK, Harris AC, Oddone EZ. Utility of hemoglobin A1c in predicting diabetes risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2004. 19:1175–1180.

12. Pradhan AD, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Hemoglobin A1c predicts diabetes but not cardiovascular disease in nondiabetic women. Am J Med. 2007. 120:720–727.

13. Sato KK, Hayashi T, Harita N, Yoneda T, Nakamura Y, Endo G, Kambe H. Combined measurement of fasting plasma glucose and A1C is effective for the prediction of type 2 diabetes: the Kansai Healthcare Study. Diabetes Care. 2009. 32:644–646.

14. Kim KS, Kim SK, Lee YK, Park SW, Cho YW. Diagnostic value of glycated haemoglobin HbA(1c) for the early detection of diabetes in high-risk subjects. Diabet Med. 2008. 25:997–1000.

15. Bae JC, Rhee EJ, Choi ES, Kim JH, Kim WJ, Yoo SH, Park SE, Park CY, Lee WY, Oh KW, Park SW, Kim SW. The cutoff value of HbA1c in predicting diabetes in Korean adults in a university hospital in Seoul. Korean Diabetes J. 2009. 33:503–510.

16. Lee YS, Moon SS. The use of HbA1c for diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in Korea. Korean J Med. 2011. 80:291–297.

17. Lee CH, Chang WJ, Chung HH, Kim HJ, Park SH, Moon JS, Lee JE, Yoon JS, Chun KA, Won KC, Cho IH, Lee HW. The combination of fasting plasma glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin as a predictor for type 2 diabetes in Korean adults. Korean Diabetes J. 2009. 33:306–314.

18. Kim CH, Kim HK, Bae SJ, Park JY, Lee KU. Discordance between fasting glucose-based and hemoglobin A1c-based diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in Koreans. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011. 91:e8–e10.

19. El-Agouza I, Abu Shahla A, Sirdah M. The effect of iron deficiency anaemia on the levels of haemoglobin subtypes: possible consequences for clinical diagnosis. Clin Lab Haematol. 2002. 24:285–289.

20. Coban E, Ozdogan M, Timuragaoglu A. Effect of iron deficiency anemia on the levels of hemoglobin A1c in nondiabetic patients. Acta Haematol. 2004. 112:126–128.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download