Abstract

Purpose

Autogenous bones are frequently used because of their lack of antigenicity, but good osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties. This study evaluated the biological behavior of perforated and nonperforated cortical block bone grafts.

Methods

Ten nonsmoking patients who required treatment due to severe resorption of the alveolar process and subsequent implant installation were included in the study. The inclusion criteria was loss of one or more teeth; the presence of atrophy of the alveolar process with the indication of reconstruction procedures to allow rehabilitation with dental implants; and the absence of systemic disease, local infection, or inflammation. The patients were randomly divided into two groups based on whether they received a perforated (inner surface) or nonperforated graft. After a 6-month healing period, a biopsy was performed and osseointegrated implants were installed in the same procedure.

Results

Fibrous connective tissue was evident at the interface in patients who received nonperforated grafts. However, full union between the graft and host bed was visible in those who had received a perforated graft.

Bone defects in the human maxilla are common and mostly determined by a premature loss of teeth due to periodontal disease or trauma. Frequently, a reduction in alveolar bone volume is also evident, which cannot be adequately treated with osseointegrated implants [1].

To create favorable conditions for implant placement, bone reconstruction or augmentation may be necessary. This involves the use of different grafting materials and techniques resulting in predictable procedures for endosseous implant placement [2]. The autogenous graft remains the gold standard for bone regeneration with a high predictability of results [3]. Among the potential donor sites, the body and ramus of the mandible are most suitable because they provide adequate, dense bone with sufficient volume for implant placement, have short healing periods, can be accessed easily, and have a low morbidity [4-6].

The autogenous bone graft is considered an excellent technique because it lacks antigenicity, but contains osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties, although direct osteogenesis derived from the graft cells is low. Moreover, it is not clear whether procedures that facilitate vascular ingrowth and substitution of the graft also favor healing. This study aimed to assess the ability of autogenous bone grafts with perforations versus those without perforations to repair critical size bone defects in rehabilitation patients with dental implants.

Patients who underwent ridge augmentation due to a bone deficiency prior to implant placement were recruited from the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Division of the Araraquara School of Dentistry, Univ Estadual Paulista. In total, 10 adult patients (6 women and 4 men; mean age, 46 years) with a loss of one or more teeth and atrophy of the alveolar process with indication for reconstructive procedures that would allow for rehabilitation with dental implants were included in the study. All patients presented without a documented medical history. Current smokers or any patients with a systemic disease or long-term corticosteroid therapy use were excluded from this study.

The treatment plan was fully explained to all patients before clinical and radiographic evaluations were carried out. The treatment protocol included (1) an operation for bone augmentation, (2) a 6-month healing period, and (3) a second surgical procedure for biopsy and implant placement. All patients provided informed consent to donate their bone tissue, which was removed during implant surgery, for histological examination. The Ethical Committee in Human Research of Araraquara Dental School, São Paulo State University, approved this protocol (#31/10).

First, the patients were randomly allocated to receive either grafts with a perforated inner surface (n=5) or grafts without a perforated surface (n=5).

All patients were anesthetized with 2% mepivacaine with epinephrine 1:100,000. Full-thickness flaps were reflected to allow the satisfactory exposure of the recipient site. In all patients, the external cortex of the host bed was perforated with a 702 fissure bur (KG Sorensen, São Paulo, Brazil).

Following the protocol by Misch et al. [6], bone was removed for grafting from the lateral mandibular body and ramus. After anesthesia, the donor area was exposed and the graft area was delineated. The osteotomies were executed with a small fissure bur to outline the dimensions of the bone block. Care was taken to penetrate only the cortical layer to avoid injury to the inferior alveolar nerve (Fig. 1). A straight elevator was placed along the sagittal cut, and the lateral block of bone was green-stick fractured and removed. Grafts in the perforated group were prepared by perforating the inner surface, which would be in contact with the host bed using a 702 fissure bur, aiming to increase surface area and facilitate vascular ingrowth (Fig. 2). In the nonperforated group, the internal surface of the bone graft was kept intact. The grafts were then fixated to the recipient site with 1.5-mm titanium screws (Conexão Prosthesis Systems, São Paulo, Brazil) (Fig. 3) [7].

Once the graft was adapted and fixated to the site, an incision through the periosteum near the base of the flap allowed the tissue to cover the graft without tension. Then, the recipient and donor areas were sutured with 6.0 nylon (Johnson & Johnson, São José dos Campos, Brazil). All patients received antibiotic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory drug therapy as well as routine clinical and radiological follow-up. The patients were instructed not to use their prosthesis for 15 days. After that, the old prostheses were adjusted and resupported with a tissue conditioner. This procedure was repeated monthly to check for soft tissue lesions suggestive of excess compression or localized trauma.

After a 6-month healing period, a biopsy was performed on the grafted bone/recipient site interface. A bone specimen measuring approximately 2.5 mm in diameter and 8-10 mm in length was removed with a 3-mm hollow trephine bur (outer diameter) under copious saline irrigation. The specimen was carefully removed from the trephine bur, and the part corresponding to the buccal side was labeled with black India ink for ease of orientation during histological preparation.

Immediately after the biopsy was taken, osseointegrated implants (Conexão Prosthesis Systems) were installed. Fixation screws were removed, and then implant site preparation and insertion were completed according to standard surgical protocols.

All specimens were immediately fixed in a 4% formaldehyde solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) at 4℃ until the implant could be embedded. All the biopsies were cold embedded in methyl methacrylate with a 20% resin solution. Nondecalcified, 5-µmthick sections were made along the axis of the biopsy. All specimens were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and examined under a light microscope for histological analyses (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Among the patients who received nonperforated grafts, the bone tissue appeared immature with large trabecular spaces, and some areas had formed new tissue (Fig. 4). In addition, fibrous connective tissue frequently appeared at the interface (Fig. 5). Areas of integration of the bone graft to the host bed were observed at only a few locations.

Among those who had received grafts with a perforated inner surface, full union between the graft and host bed was observed (Fig. 6). For all patients in this group, integration between the graft and recipient sites was found, with few areas of connective tissue at the interface (Fig. 7). Upon clinical inspection, the volume of the perforated graft was better maintained and stability was higher than with the nonperforated graft.

Several procedures have been proposed to obtain alveolar ridge augmentation in partially edentulous patients [8]. However, the most extensively employed procedure for those reconstructions are autogenous bone grafts. In the case of bone grafts, two-stage procedures seem to provide improved results [9,10].

Autogenous block bone grafts are the preferred method for many types of augmentation procedures. These grafts create a source of viable cells and proteins and provide a scaffold for new bone formation, but without antigenicity [11]. Revascularization of a bone graft is critical for cell survival and graft incorporation [12]. To improve the incorporation of such grafts, cortical perforations in donor sites have been suggested to increase the surface area and open the medullary cavity [12-14].

Although membranous bone grafts of the face are described as capable of maintaining their volume better than bone grafts of endochondral origin, volume maintenance may be more a function of the physical characteristics of the grafted bone than anything else [15]. The body and ascending ramus of the mandible present a large amount of cortical bone. The cancellous portion of the bone graft has an important function, stimulating the osteogenic cells and undifferentiated marrow cells to grow and lay down bone on their surface. Initially, the cancellous bone promotes an inflammatory reaction characterized by the formation of a clot and dilation of adjacent blood vessels [16]. Osteoblasts from the host bed and some that have survived on the graft begin to secrete bone matrix while osteoinduction acts on the cells to promote further bone formation. Nonvital bone resorption and replacement by new bone is completed after only several months.

Cortical bone has to undergo resorption by osteoclasts prior to invasion by blood capillaries and new bone formation due to its dense architecture. Moreover, cortical bone revascularization is slower than that of cancellous bone, which has spaces for vascular and tissue ingrowth (trabeculae) and a large surface area that allows for direct bone formation. Thus, bone substitution in cortical bone grafts is relatively slow, but the volume of these grafts is more stable. However, cancellous bone grafts undergo fast substitution, but loose more volume than do cortical bone grafts, especially if cancellous bone grafts are used for onlay grafting under soft tissue compression [17].

Our results indicated that the corticocancellous block grafts harvested from the mandibular ramus are reliable with a high success rate for alveolar reconstructive procedures, which are similar to the findings of previous studies [4,18]. In this study, morbidity was very low and the main symptoms included postoperative edema, pain, and occasionally transient hypoesthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve. During the second procedure, clinical evaluations demonstrated greater stability and better maintenance of the graft volume for the perforated grafts than that of the nonperforated grafts. Moreover, the histological evaluation indicated that a greater area of the graft was in direct contact with the host's bed bone and a greater amount of bone was incorporated into it, with a much smaller area of connective tissue at the graft/host bed interface in the perforated grafts than that of the nonperforated grafts. These factors account for the improved stability and decreased chance of the graft loosening, which is sometimes observed clinically.

According to Rompen et al. [13] perforations of the bone cortex create a bleeding surface that results in a layer of granulated tissue at the bone surface. Bone augmentation chambers were placed bilaterally on the rat calvaria and they demonstrated that cortical perforations increased skull thickness when compared to nonperforated controls at 8 and 16 weeks postoperatively. This highly vascularized tissue became mineralized, thus enhancing new bone formation [13].

However, Slotte and Lundgren [19] evaluated whether perforations in the donor bone marrow through the cortical plate would enhance bone formation in adjacent experimentally created space in the skulls of eight rabbits. The authors perforated about one-third of the cortical bone plate with seven evenly distributed holes, each with a diameter of 1.2 mm (experimental bone area) [19]. The bone on the control side was left intact and no bleeding occurred during the placement of the titanium lid [19]. No statistical differences were observed between the perforated test sites and the control sites in relation to the augmented bone volume [19].

In addition, Barbosa et al. [20] performed a histologic assessment in 12 rabbits for the amount of bone matrix in autogenous bone grafts that were fixated with or without perforation in cortical bone receptor sites. Osteotomies were performed bilaterally in the anterior parietal region. The bone was removed, perforated with a 0.9 mm helical bur, and fixed to the adjacent area 3 mm from the border of the osteotomy. On the contralateral side, six perforations were made in the receptor site using a round bur with a diameter of 0.5 mm. Both the periosteum and the skin were repositioned under primary closure [20]. After 28 days, the animals were sacrificed, and the tissues were removed for histomorphometric analysis. No significant differences in the total area of the grafts between the perforated and nonperforated sides were found [20].

Acocella et al. [18] stated that the mechanism of incorporation of bone block grafts into the surrounding bone is still unknown. The uncertainty stems from the results of some studies that do not show any benefit of perforated grafts as opposed to nonperforated grafts [19-22].

In this study, the density of the grafted bone may influence its level of incorporation and subsequent substitution, as was noted in our nonperforated group. Perforations of a partial thickness on the inner sides of the graft may have enhanced incorporation of the graft perhaps by increasing the surface area and facilitating tissue and vascular ingrowth.

In this study, reconstruction with autogenous bone grafts predictably recovered bone function and esthetics in patients with critical size defects. Periosteal preservation appears to be a serious factor in maintaining long-term stable bone volume in bone grafts. The partial thickness perforations of the inner sides of the graft may have enhanced incorporation of the graft to the host bed by increasing the surface area, facilitating tissue and vascular ingrowth, and enhancing the healing process (osteogenesis). In addition, bone graft perforations seem to improve clinical stability for the placement of dental implants. Within the limitations of this study, we found that intentional perforations in block bone grafts may influence the volume of the graft. In our nonperforated group, the density of the grafted bone may have caused difficulty in the incorporation and subsequent substitution of the graft.

Figures and Tables

Figure 4

On the inner side of the nonperforated bone graft, observations of immature bone, large trabecular spaces, and some areas of newly formed bone is possible (H&E, ×250). Black asterisks indicate the inner side of nonperforated bone graft and the presence of osteoclasts and bone resorption characterized by the presence of innumerous inflammatory cells like macrophages. Red asterisks indicate recently formed connective tissue with innumerous blood vessels.

Figure 5

Nonperforated bone graft interface and the host bed with immature tissue (H&E, ×250). Black asterisk indicates the nonperforated bone graft with osteoclasts present. Red asterisk indicates the immature connective tissue interface in the supracrestal region.

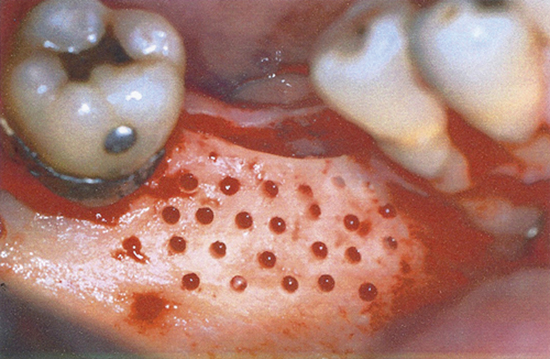

Figure 6

The inner side of the perforated bone graft with the perforated region created by cylindrical burs. Neoformed bone tissue characterized by the presence of innumerous osteocytes and medullary space and remodeling bone tissue with various osteoclasts are also present (H&E, ×250).

Figure 7

Perforated region of the bone graft and host bed with a slight presence of connective tissue (H&E, ×250). Black asterisk indicates bone tissue from the receptor bed with innumerous osteocytes. Red asterisk indicates the inner side of the perforated bone tissue with meduallary spaces, osteoclasts, and osteocytes.

References

1. Oikarinen KS, Sandor GK, Kainulainen VT, Salonen-Kemppi M. Augmentation of the narrow traumatized anterior alveolar ridge to facilitate dental implant placement. Dent Traumatol. 2003; 19:19–29.

2. Chiapasco M, Zaniboni M, Rimondini L. Autogenous onlay bone grafts vs. alveolar distraction osteogenesis for the correction of vertically deficient edentulous ridges: a 2-4-year prospective study on humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007; 18:432–440.

3. Jensen J, Sindet-Pedersen S. Autogenous mandibular bone grafts and osseointegrated implants for reconstruction of the severely atrophied maxilla: a preliminary report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991; 49:1277–1287.

4. Garg AK, Morales MJ, Navarro I, Duarte F. Autogenous mandibular bone grafts in the treatment of the resorbed maxillary anterior alveolar ridge: rationale and approach. Implant Dent. 1998; 7:169–176.

5. Schwartz-Arad D, Levin L. Intraoral autogenous block onlay bone grafting for extensive reconstruction of atrophic maxillary alveolar ridges. J Periodontol. 2005; 76:636–641.

6. Misch CM, Misch CE, Resnik RR, Ismail YH. Reconstruction of maxillary alveolar defects with mandibular symphysis grafts for dental implants: a preliminary procedural report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992; 7:360–366.

7. Scaf de Molon R, de Avila ED, Scartezini GR, Bonini Campos JA, Vaz LG, Real Gabrielli MF, et al. In vitro comparison of 1.5 mm vs. 2.0 mm screws for fixation in the sagittal split osteotomy. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2011; 39:574–577.

8. Buser D, Dula K, Belser UC, Hirt HP, Berthold H. Localized ridge augmentation using guided bone regeneration. II. Surgical procedure in the mandible. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1995; 15:10–29.

9. Sjöström M, Lundgren S, Sennerby L. A histomorphometric comparison of the bone graft-titanium interface between interpositional and onlay/inlay bone grafting techniques. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2006; 21:52–62.

10. Lundgren S, Rasmusson L, Sjostrom M, Sennerby L. Simultaneous or delayed placement of titanium implants in free autogenous iliac bone grafts. Histological analysis of the bone graft-titanium interface in 10 consecutive patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999; 28:31–37.

11. Lew D, Marino AA, Startzell JM, Keller JC. A comparative study of osseointegration of titanium implants in corticocancellous block and corticocancellous chip grafts in canine ilium. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 52:952–958.

12. Faria PE, Okamoto R, Bonilha-Neto RM, Xavier SP, Santos AC, Salata LA. Immunohistochemical, tomographic and histological study on onlay iliac grafts remodeling. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008; 19:393–401.

13. Rompen EH, Biewer R, Vanheusden A, Zahedi S, Nusgens B. The influence of cortical perforations and of space filling with peripheral blood on the kinetics of guided bone generation. A comparative histometric study in the rat. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1999; 10:85–94.

14. Delloye C, Simon P, Nyssen-Behets C, Banse X, Bresler F, Schmitt D. Perforations of cortical bone allografts improve their incorporation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002; (396):240–247.

15. Smolka W, Eggensperger N, Carollo V, Ozdoba C, Iizuka T. Changes in the volume and density of calvarial split bone grafts after alveolar ridge augmentation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006; 17:149–155.

16. Pallesen L, Schou S, Aaboe M, Hjorting-Hansen E, Nattestad A, Melsen F. Influence of particle size of autogenous bone grafts on the early stages of bone regeneration: a histologic and stereologic study in rabbit calvarium. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2002; 17:498–506.

17. Sbordone L, Toti P, Menchini-Fabris GB, Sbordone C, Piombino P, Guidetti F. Volume changes of autogenous bone grafts after alveolar ridge augmentation of atrophic maxillae and mandibles. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 38:1059–1065.

18. Acocella A, Bertolai R, Colafranceschi M, Sacco R. Clinical, histological and histomorphometric evaluation of the healing of mandibular ramus bone block grafts for alveolar ridge augmentation before implant placement. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2010; 38:222–230.

19. Slotte C, Lundgren D. Impact of cortical perforations of contiguous donor bone in a guided bone augmentation procedure: an experimental study in the rabbit skull. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2002; 4:1–10.

20. Barbosa DZ, de Assis WF, Shirato FB, Moura CC, Silva CJ, Dechichi P. Autogenous bone graft with or without perforation of the receptor bed: histologic study in rabbit calvaria. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009; 24:463–468.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download