Abstract

Purpose

To assess the progression of clinical symptoms and disease course of calcific tendinitis in the hip region according to types of calcification.

Materials and Methods

Among patients with the hip pain, 28 patients (21 males and 7 females; mean age 51 years, range 32-74 years) showing calcified lesions in simple radiography without other possible sources of pain were analyzed retrospectively. Twelve patients displayed a symptom duration of less than three weeks (acute; average=1±0.9 week) and 16 displayed greater than three weeks (chronic; average=21.0±19.5 weeks). Lesions were classified as nodular (11, 39.3%), nodular-fragmented (13, 46.4%), or amorphous (4, 14.3%). Initial symptoms, progression of clinical features, radiological findings and prognosis were investigated and analyzed according to calcification type.

Results

In 15 patients (53.6%), lesions were located superior to the great trochanter. On average, the acute group was younger (44.58 vs. 55.44 years, P=0.006), suffered more (mean pain Numeric Rating Scale [NRS], 6.3 vs. 3.8; P<0.001), and recovered more (difference between initial and follow-up NRS, 5.1 vs. 2.63; <<0.001) than the chronic group. The mean length of initial lesions was longer in the acute group than the chronic group (15.8 vs. 9.1 mm, P=0.008). When compared to patients with distinctive margins (15, 53.6%), those with nondistinctive margins showed better improvement (difference between initial and follow-up NRS, 4.7 vs. 2.8; P=0.01) and more significant decrease in lesion size (difference between initial and follow-up length, 10.8 vs. 2.6 mm; P=0.003).

Conclusion

Calcific tendinitis occurring in the hip area displayed a variety of characteristics. Although complaining of more severe pain in the initial phase, patients with acute pain or calcific lesions with nondistinctive margins showed better symptom improvement when compared to their counterparts.

Calcific tendinitis, also known as hydroyapatite deposition disease, commonly occurs in the rotator cuff and is usually accompanied by severe pain1). Although calcific tendinitis occurring in the hip is also accompanied by severe pain, accurate diagnosis can be difficult due to the presence of atypical symptoms and low prevalence2). Painful calcific tendinitis around the hip is commonly seen in the greater trochanter and usually occurs in the bursa between the gluteus medius tendon and the greater trochanter34). Ultrasound is often used to determine the exact location and shape of lesions56). A variety of treatment modalities have been introduced such as simple observation, administration of oral anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics, local injection of steroids, multiple puncture, extracorporeal shock wave therapy or other surgical interventions789). Previous investigations include mostly single-patient case reports or studies on calcification types and treatment results in a small number of patients due to relatively low prevalence10) and discontinuation of follow-up after pain relief81112). Although multiple studies have shown satisfactory results with conservative treatment, other case reports reported improvement after repeated injections or surgical management213). Since the classification of calcific lesion types and follow-up of changes in lesion size have been rarely studied13), predicting prognosis or deciding on the approach for clinical intervention approach has primarily been based on the physician's experience.

This study aimed to examine changes in clinical progression and radiologic images and compare prognostic differences according to symptoms and lesion location, size and pattern of calcification in patients with calcific tendinitis in the hip following conservative treatment.

This study included a total of 28 patients who visited our hospital with a chief complaint of hip pain from June 2009 to July 2015 who displayed calcific lesions on simple radiographs. Exclusion criteria included patients with: i) other clinical or radiologic findings that cause pain; ii) other diseases; iii) pain in other sites without other possible underlying pain source; iv) radiating lumbar pain; and v) a history of the same symptoms or hip surgery on ipsilateral side. Blood tests were used to exclude patients with infectious lesions, systemic diseases, or acute inflammatory lesions. Bone scan, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were also conducted for patients with other conditions that needed to be differentiated from calcific lesions (bone scan, 10; CT, 1; MRI, 10).

A sudden onset of symptoms with a duration of less than 3 weeks duration was defined as acute pain and more than 3 weeks as chronic pain. Physical examinations were performed by a single surgeon. Hip range of motion (ROM), straight leg raising, Patrick's test, log rolling, pain during flexion and internal rotation, and tenderness and crepitation in calcific lesion area on plain radiographs were examined in a supine position. The Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) was used to determine the severity of pain. At follow-up periods, physical examination same as the initial diagnosis, severity of pain, and treatment satisfaction surveys (very satisfied, satisfied, somewhat satisfied, not satisfied, not very satisfied) were also conducted. Follow-up treatments were conducted at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial visit. Follow-ups were carried out on the second and third months according to symptoms. Five patients who had not been followed up were interviewed by phone to assess changes in symptoms, additional therapies, the use of oral drugs, satisfaction for treatment and possible ROM.

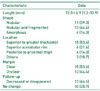

Anteroposterior, frog leg and Sugioka views of the hip were taken at the initial visit in all 28 patients. Bone scan (technetium-99m), CT or MRI imaging was followed if necessary. The positions of calcific lesions were classified according to location seen on plain radiographs and additional CT or MRI images as following: superior to the great trochanter (the insertion site of gluteus medius), superior aspect of the acetabulum (the origin of rectus femoris), posterior to the proximal femur (the origin of adductor), inferior to the great trochanter (the origin of vastus lateralis), and inferior to anterior superior iliac spine (the origin of sartorius). The size of the calcific lesion was measured as the longest major axis on the plain radiograph. When performing CT, the maximum value was used among lengths measured on sagittal, coronal and horizontal planes. The average of 6 measurements conducted 3 times each by two surgeons was used. Calcific lesions were divided into nodular, nodular-fragmented and amorphous, according to their shapes observed on plain radiographs14) (Fig. 1). In addition, lesions were classified into distinctive and non-distinctive groups according to margin distinctiveness seen on radiographs. Plain radiographic follow-up (3 months on average) was performed in 23 out of 28 subjects.

After informing patients of diagnosis, the use of oral anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics was recommended. Three patients who preferred simple observation received no treatment but follow ups were conducted. Those who complained of moderate to severe pain or preferred active treatment received local injection or extracorporeal shock wave therapy. Oral anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics were prescribed to 20 patients. Aceclofenac (Airtal; Daewoong Pharm., Sungnam, Korea) 100 mg twice a day was prescribed to 16 patients, and celecoxib (Celebrex; Pfizer, Seoul, Korea) 200 mg four times a day, piroxicam (Brexin; Kolon Pharm., Gwacheon, Korea) 10 mg twice a day, acetaminophen (Tylenol; Janssen, Seoul, Korea) 650 mg three times a day, and pelubiprofen (Pelubi; Daewon Pharm., Seoul, Korea) 30 mg three times a day were prescribed for one patient each. The mean intake duration was 19 days. Local injections of triamcinolon 40 mg+1% lidocaine 1 mL were administered as direct injection in two patients. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy was applied to three patients who rejected the use of oral analgesics for a total of five sessions carried out on a weekly basis. An electromagnetic-focused shock wave device (Swiss Dolorclast® Classic; Electro Medical Systems, Nyon, Switzerland) was used at an intensity of 8, 5.0 Hz and 2000 impulses. Ultrasound gel was used to minimize energy loss at the interface between the skin and the shock wave source device.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Student's t-test was used to assess differences in disease duration, NRS pain score, change in lesion size and relieving duration. A chi-square test was used to evaluate data on lesion sizes and treatments between acute and chronic groups. Five patients who had not been followed up were excluded from statistical analysis of follow-up radiographs.

The mean age of patients was 51 years (range, 32-74 years). Subjects were 21 male (75.0%) and 7 female (25.0%). The affected hip was the right side in 15 (53.6%) cases and the left side in 13 cases (46.4%). The average duration of onset of symptoms to hospital admission was 1.0±0.9 weeks in acute cases (12 hips, 42.9%) and 21.0±19.5 weeks in chronic cases (16 hips, 57.1%). At the time of initial admission, patient complaints were hip pain (13 cases, 46.4%), groin pain (8 cases, 28.6%) and thigh pain (7 cases, 25.0%). Upon physical examination, Patrick's test was positive in 16 cases (57.1%) regardless of calcific lesion location, and tenderness in calcified lesion areas was observed in 15 cases (53.6%) (Table 1). The most common location of lesions was superior to the great trochanter of femur in 15 (53.6%), followed by superior aspect of the acetabulum in 6 (21.4%), posterior aspect of the proximal femur in 4 (14.3%), inferior to the great trochanter in 2, and anterior superior iliac spine in 1. The average length of the major axis of initial calcific lesions was 12.0±6.9 mm. Lesion types were classified as nodular in 11 (39.3%), nodular-fragmented in 13 (46.4%), and amorphous in 4 (14.3%). Calcific lesions had a distinctive margin in 15 (53.6%) and a non-distinctive margin in 13 (46.4%). Lesions were decreased in size or disappeared on follow-up images in 13 (46.4%) (Table 2).

The mean age for patients with an acute condition was younger than those with a chronic condition (44.6±7.2 years vs. 55.4±11.0 years; P=0.006). The male to female ratio was 2 in the acute group (8 men and 4 women) and 4.33 in the chronic group (13 men and 3 women) (P=0.378). There were five individuals with distinctive margins and seven with non-distinctive margins (acute group) compared to 10 with distinctive margins and six with non-distinctive margins (chronic group) (P=0.239). The average size of the initial calcific lesions (15.8±7.0 mm) in the acute group was larger (P=0.008) than those in the chronic group (9.1±5.3 mm). The follow-up lesion size was 5.9±7.0 mm in the acute group compared to 6.7±4.5 mm in the chronic group (P=0.730). In the acute group, the average reduced size of lesions was 5.1±1.9 mm compared to 2.8±4.8mm in the chronic group (P=0.012). On follow-up radiographs, 10 patients in the acute group (83.3%) showed a decrease in lesion size or lesion regression compared to three (18.8%) in the chronic group (P=0.007). The initial NRS pain score was 6.3±1.8 in acute and 3.8±1.1 in chronic (P<0.001). The follow-up NRS score was 1.3±1.0 in acute pain and 1.1±0.7 in chronic pain (P=0.697). The difference between initial and follow-up NRS scores was 5.1±2.0 in the acute group and 2.6±1.4 in the chronic group (P<0.001). The mean duration of symptom improvement perceived by patients after treatment was 11.4 days vs. 24.8 days in the acute and chronic groups, respectively, implying more significant improvement of symptoms in the acute phase (P=0.01). When compared across treatment modalities, the mean duration of symptom improvement after oral administration was 16.9 days and after local injection or extracorporeal shock wave therapy was 7 days (P=0.062). When treatment satisfaction was compared across groups, the acute group breakdown was: i) very satisfied (3, 25%), satisfied (6, 50%), and somewhat satisfied (3, 25%) and for the chronic group, responses were split equally between: i) satisfied (8, 50%) and somewhat satisfied (8, 50%) (Table 3).

The mean age according to margin distinctiveness was 51.4±.5 years vs. 50.1±2.7 years in the distinctive margin and non-distinctive margin groups, respectively (P=0.755). Interestingly, the average duration of onset of symptoms to hospital admission was 17.0±9.7 weeks vs. 7.1±4.1 weeks in the distinctive and non-distinctive groups, respectively (P=0.143). The average size of initial lesions was 10.5±.1 mm for the distinctive margin group compared to 13.7±.5 mm for the group with non-distinctive margins (P=0.228). When follow-up size of lesions were compared, we saw a difference between the distinctive and non-distinctive groups (8.7±.9 mm vs. 4.0±.0 mm; P=0.067). The average reduction in follow-up lesion sizes was 2.6±.5 mm vs. 10.8±.2 mm in the distinctive margin group compared to the non-distinctive margin group (P=0.003). On follow-up radiographs, a statistically significant difference (P=0.011) in the number of individuals showing a decrease in lesion size or lesion regression was observed (3 patients [20.0%] from the distinctive margin group compared to 10 [77.0%] in the non-distinctive group). The initial NRS score was 4.2±1.8 and 5.6±.9 in the distinctive and non-distinctive groups, respectively (P=0.052), and the follow-up NRS scores were 1.4±.9 and 0.9±.6 in the distinctive vs. non-distinctive groups, respectively (P=0.126). A difference between initial and follow-up scores was 2.8 ±.0 in the distinctive group compared to 4.7±.6 in the non-distinctive group (P=0.01). Treatment satisfaction breakdowns are presented in Table 4 and show that one (6.7%), 4 (26.7%) and 10 (66.7%) individuals were very satisfied, satisfied, and somewhat satisfied, respectively in the distinctive group. In the non-distinctive group, however, 2 individuals (15.4%) were very satisfied, 10 (76.9%) were satisfied and only one (7.7%) was somewhat satisfied in one (7.7%) (P=0.006; Table 4).

Calcific tendinitis can occur in the shoulder, hip and different parts of the body, but accurate diagnosis can often be difficult due to atypical symptoms and low incidence, specifically in the hip231516). Bosworth17) have suggested repetitive exercises and chronic overload of the muscle's insertion as possible causes. Uhthoff et al.18) have indicated that breakdown of calcific deposits induce pain during the absorption process of calcification developed by hypoxia resulting from focal ischemia caused by phagocytic activity of macrophages. In the resorptive phase (one of the stages of calcification according to histological findings), lesions usually have indistinct margins on simple radiographs and are often accompanied by pain18). Moreover, Gärtner and Simons14) have reported that there are no changes in mineral composition in different clinical stages of calcific tendinitis, and changes in binding force between minerals in acute phase promote phagocytic activity by inducing breakdown of calcific crystals. After calcific lesions are phagocytized by macrophages, phospholipase A2 enzymes are activated, protease activity increases, and accumulates are dissolved as the calcified region is exposed to an acidic environment19).

Although calcific tendinitis of the hip can occur in people of different ages, it is more common in middle-aged adults and the initial phase is associated with moderate pain. The most common site of onset is superior to the great trochanter, serving as an attachment site of the gluteus medius, and pressure pain and positive for Patrick's test were seen13). In the present study, calcific tendinitis most frequently occurred superior to the great trochanter, and patients showed various clinical manifestations. Calcific tendinitis of the hip has a wider range of clinical manifestations than that of the shoulder, and various onset sites are thought to be attributable to muscles located deep within the hip.

Previous studies on calcific tendinitis have mainly focused on treating patients with acute severe symptoms. Of these, local injection, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, surgical resection and other therapies were performed on patients after failure of conservative treatment according to some case reports456913). This study analyzed calcific tendinitis by separating cases into acute and chronic phases, and differences in pain characteristics and symptom improvement were observed across these groups. Initial size of calcific lesions and a decrease in lesion size was greater in acute phase. The duration of symptom improvement was shorter in those with acute pain than those with chronic pain, and this can be considered as related to the disease course19).

According to a study of Lee et al.20), duration and regression of symptoms took a shorter period of time in calcification with a fluffy margin than with a distinctive margin. In this study, patients with calcific lesions with indistinct margins on radiographs complained of more severe pain. However, lesions were decreased in size or subsided in follow-up radiographs in a greater number of cases. Lesions with non-distinctive margin can be determined in the resorptive phase, one of the histological stages defined by Uhthoff et al18). Thus, a decrease in lesion size occurred in most cases (75.0%) at follow-up. The outcome is more commonly seen in patients in the chronic phase.

Calcific lesions are commonly managed with conservative treatment using anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics18), and local injection or extracorporeal shock wave therapies are attempted for large lesions or after failure of conservative treatments28). For large and painful lesions, surgery is performed in place of spontaneous resorption13). Instead of extracorporeal shock wave therapy alone, the combined use of anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics and local injection therapy are applied8). Compared to the administration of oral anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics, a local injection of adrenocortical hormone in combination with local anesthetic has shown a more immediate improvement in symptoms1). Faure and Daculsi21) have suggested that local steroid injections need to be carefully used to reduce inflammation caused by calcific lesions due to the risk of infection, and the potential development of local necrosis resulted from intratendinous injections. In this investigation, the authors applied conservative treatment in 23 cases (82.1%), including observation or administration of oral anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics and local injection therapy in three cases. Although symptoms improved faster in patients who underwent local injection therapy compared to those who received analgesics alone, no statistical significance was found.

This study has some limitations. The statistical significance of results is limited by the retrospective nature of the study. Since all patients did not receive follow ups, some patients were inquired by phone regarding their changes in symptoms. In addition, simple radiography was not performed in all patients. Furthermore, identifying the exact time of lesion regression is limited by the relatively short and inconsistent follow-up periods. Even though the size of calcific lesions was measured repeatedly to reduce possible errors, the measurement method used has a limitation in reflecting the volume or actual size of lesions. However, the results are thought to sufficiently explore patterns in changes of lesion size. The clinical manifestations of calcific lesions are subjectively classified and interobserver errors may occur. Since only a few studies have investigated the radiographic interpretations of calcific lesions, further studies are warranted.

Calcific tendinitis occurring in the hip area displayed a variety of characteristics, and conservative treatment was enough to control symptoms in most cases. Although complaining of more severe pain in the initial phase, patients with acute pain or calcific lesions with non-distinctive margins showed better symptom improvement when compared to their counterparts.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Simple radiographs demonstrate 3 calcification types at superior aspect of greater trochanter. (A) Nodular type, (B) nodular-fragmented type, (C) amorphous type.

References

1. Choi JC, Kim YH, Na HY, et al. Treatment of calcific tendinitis around hip joint. J Korean Hip Soc. 2005; 17:83–87.

2. Sarkar JS, Haddad FS, Crean SV, Brooks P. Acute calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996; 78:814–816.

3. Holt PD, Keats TE. Calcific tendinitis: a review of the usual and unusual. Skeletal Radiol. 1993; 22:1–9.

4. Ahn GY, Jang JH, Yun HH. Calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris around the hip joint. Hip Pelvis. 2006; 18:73–78.

5. Aina R, Cardinal E, Bureau NJ, Aubin B, Brassard P. Calcific shoulder tendinitis: treatment with modified US-guided fine-needle technique. Radiology. 2001; 221:455–461.

6. del Cura JL, Torre I, Zabala R, Legórburu A. Sonographically guided percutaneous needle lavage in calcific tendinitis of the shoulder: short- and long-term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007; 189:W128–W134.

7. Kim YS, Lee HM, Kim JP. Acute calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris associated with intraosseous involvement: a case report with serial CT and MRI findings. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2013; 23:Suppl 2. S233–S239.

8. Oh KJ, Yoon JR, Shin DS, Yang JH. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for calcific tendinitis at unusual sites around the hip. Orthopedics. 2010; 33:769.

9. Peng X, Feng Y, Chen G, Yang L. Arthroscopic treatment of chronically painful calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris. Eur J Med Res. 2013; 18:49.

10. Pope TL Jr, Keats TE. Case report 733. Calcific tendinitis of the origin of the medial and lateral heads of the rectus femoris muscle and the anterior iliac spin (AIIS). Skeletal Radiol. 1992; 21:271–272.

11. Seo YJ, Chang JD, Chang SK, Lee GK. Calcific tendinitis of the rectus femoris: a case report. J Korean Orthop Assoc. 2004; 39:343–346.

12. Paik NC. Acute calcific tendinitis of the gluteus medius: an uncommon source for back, buttock, and thigh pain. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014; 43:824–829.

13. Park SM, Baek JH, Ko YB, Lee HJ, Park KJ, Ha YC. Management of acute calcific tendinitis around the hip joint. Am J Sports Med. 2014; 42:2659–2665.

14. Gärtner J, Simons B. Analysis of calcific deposits in calcifying tendinitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990; (254):111–120.

15. Neviaser RJ. Painful conditions affecting the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983; (173):63–69.

16. Johnson GS, Guly HR. Acute calcific periarthritis outside the shoulder: a frequently misdiagnosed condition. J Accid Emerg Med. 1994; 11:198–200.

17. Bosworth BM. Calcium deposits in the shoulder and subacromial bursitis: a survey of 12,122 shoulders. JAMA. 1941; 116:2477–2482.

18. Uhthoff HK, Sarkar K, Maynard JA. Calcifying tendinitis: a new concept of its pathogenesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976; (118):164–168.

19. Sakai T, Shimaoka Y, Sugimoto M, Koizumi T. Acute calcific tendinitis of the gluteus medius: a case report with serial magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Orthop Sci. 2004; 9:404–407.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download