Abstract

Periprosthetic joint infection is one of the most dreaded complications of replacement arthroplasty and the incidence of periprosthetic tuberculous infections is increasing. This report presents a case of extensive periprosthetic tuberculous infections of primary total hip arthroplasty which was treated with debridement and long periods of antituberculous medication without implant removal. The patient completed 18 months of 4 drug antituberculous chemotherapy and the plain radiograph on the last review showed new bony consolidation around the prosthesis without loosening or signs of reactivation.

Tuberculosis (TB) infection is in a rising trend in the developed world because of compromised immune system by immunosuppressive drugs, substance abuse, or AIDS and as the result of immigrants from endemic countries. With this current trend, orthopaedic surgeons are increasingly likely to encounter patients affected with this disease1). There have been reports2) of total hip arthroplasty (THA) following TB infection and now, there is a rise in reports in patients with periprosthetic TB infection with no previous evidence of TB exposure1,3-7). As we are aware that diagnosis in TB periprosthetic joint or any TB joint is difficult and a misdiagnosis is common1,7). Furthermore, in the presence of total joint prosthesis, TB reactivation is even more difficult to diagnose, because radiographs, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and bone scanning are of limited value5). However, in TB periprosthetic infection early detection and adequate treatment is essential to avoid revisional arthroplasty7). Similarly, Kreder and Davey5) concluded even though periprosthetic TB infection is uncommon; it can be managed well if the diagnosis is achieved early and treated correctly.

Now we report a case of extensive periprosthetic TB infection of primary THA which was treated without implant removal. The patient and his family members gave their consent for publication of the case details.

A 64 years old man who presented in November 2004 complaining of right groin and hip pain related to activity. He gave history of bilateral primary THA (DePuy, Cup: Duraloc, Stem: AML, Liner: Duraloc polyethylene liner) of both the femoral head in 1992 for presumed avascular necrosis of femoral head. At no time there has been any sinus or signs of infection. He was well for 12 years but started to have right groin and hip pain for 1 month. The pain was progressive in nature till, he was restricted to using a walking stick and essential confirmed to his house. His general health was good as he did not give any history of previous contact with TB and no other medical history, no trauma nor other constitutional symptoms.

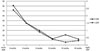

On physical exams, he could not walk without a walking stick. There was a limited range of motion of right hip due to pain and wasting of right quadriceps muscle mass was observed. He had no signs of inflammation nor sinus discharge around the right hip. The plain radiograph revealed periprosthetic bony destruction but the implants were intact with no displacement or loosening (Fig. 1). The routine ESR was 90 mm in the 1st hour, C-reactive protein (CRP) was 2.5 mg/dl and total white blood cell (WBC) count was 10,000/mm3. The chest radiograph was clear with no signs of TB and the tuberculin test was negative. The sputum and urine sample was sent to look for other sites of TB infection, but was negative.

Subsequently, he underwent debridement and curettage for his periprosthetic hip infection. Intraoperatively, there was no obvious pus or slough but the synovium was inflamed and synovial fluid was brownish in color and there was bony destruction around the right proximal femur. Thorough debridement of all infected tissue including implant removal seemed to be very difficult because prosthetic implants were stable and well fixed, so it was decided not to do an extensive debridement and to retain the implants. Based on histopathological exams of the debrided sample, the diagnosis of TB was confirmed when the synovial tissue biopsy showed chronic inflammatory caseating granuloma and Antituberculous medication (ATM) was started at third day of the debridement. He was treated daily with the following oral ATM: isoniazid(5 mg/kg), rifampicin (10 mg/kg), ethambutol(15 mg/kg) and pyrazanamide (20 mg/kg) for 18 months.

The patient showed remarkable clinical and laboratory recovery, whereby the right hip pain was no more a hindrance for him to walk without a walking aid and the blood parameters for infection was on down trend, CRP was below 0.3 mg/dL and ESR below 20 mm/hr for 6 consecutive months after 12 months of ATM (Fig. 2). Currently, he is still on our outpatient follow-up of seven years and he had completed 18 months of ATM. On the 8 years follow-up, the radiograph showed bony consolidation without loosening of the prosthesis (Fig. 1) and his CRP level was below 0.3 mg/dL and ESR below 20 mm/hr.

Prosthetic joint infection due to TB is increasing in trend in our clinical practice. Till today, there are 24 cases reported of TB periprosthetic joint infection without history of pulmonary or extra-pulmonary tuberculosis1,3-5,7-9) (Table 1). In 1977 McCullough8) was the first to report a case of TB infection that followed THA 7 years later without prior history of TB infection. Baldini et al.3) reported a case of early failure of THA 21 months after surgery because of TB and it was during removal of prosthesis that diagnosis of TB was made.

Methods of treatment for tuberculous periprosthetic infection varies from debridement without removal of well-fixed implants to resectional arthroplasty depending on surgeons and condition of hip joint. Besser6) reported TB infection of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in unsuspected patient. He retained the prosthesis and started ATM based on clinical suspicion of TB which was confirmed by synovial biopsy. Boéri et al.4) in 2003 retained THA prosthesis in TB infection where the prosthesis was stable, well fixed and there was insufficient bone stock. This case is the only report after Boéri et al.4) that a TB periprosthetic implant was retained due to insufficient bone stock and the prosthesis was well fixed. However, Marmor1) reported favorable outcomes with and without removal of the prosthesis with ATM. He retained TKA prosthesis when the infection is recognized early in one case and 2 staged revision TKA for the other two cases which was recognized late.

In this case, the infection was unexpected; a high index of suspicion of TB was always in our mind. Kreder and Davey5) concluded that when dealing with unexpected arthroplasty failure, the suspicion of TB is necessary. In this case, the TB periprosthetic infection was extensive. When the patient visited our hospital his initial symptoms had been deveoped 1 month before, and he had got primary THA 12 years before. We initially thought the infection caused by local reactivation or hematogeneous spread but don't know exactly when the infection actually started. Medical therapy often fails when the infection is discovered months or years after arthroplasty. And removal of the prosthesis and ATM is necessary for a treatment2). But interval from total joint replacement to onset of disease varied from 2 months to 38 years1,3-5,7-9) (Table 1). Cases which had no previous history of TB, but revealed active infection like pulmonary TB on further investigation, were presumed to be spreaded by hematogeneous route. Similarly, Marmor1) did a full survey for TB and there was one case of TB prosthetic knee infection with severe TB urinary tract infection who underwent a nephrectomy. A full survey for TB infection was done for this case where the sputum and urine for acid fast bacilli, tuberculin test and chest radiograph, were all negative.

Regardless of the time of the diagnosis, the treatment options available are treating with ATM with or without removal of prosthetic implant1). In cases where the prosthesis did not show signs of loosening and ATM started promptly has a good chance of retaining the prosthetic implant1). Some support the prosthetic implant removal when there is late onset of TB infection and others support the retaining the prosthetic implant, provided the prosthesis is stable and not loose. Usually, a two-stage reconstruction for failed THA due to bacterial infection has become generally accepted. But, in TB infected hip joint, it can be treated by primary THA as shown by Yoon et al.2) that there was no reactivation of TB in 7 cases of immediate cementless THA in advanced active TB arthritis of hip. Kreder and Davey5) reported a single-stage revision in THA revision with TB infection which has been treated with ATM, provided there is no more documented infection from hip aspirate.

As we know the mainstay for any TB infection is ATM but there is no proper consensus for the duration of treatment and which drugs to use for periprosthetic infection. The duration of ATM varied from 6 months to 36 months1,3-5,7-9) (Table 1). However, Sidhu et al.10) recommended prolong duration of ATM for 18 months from his series of 23 patients of THA in active advanced TB arthritis. Yoon et al.2) used ATM for 12 months in active TB hip who underwent THA, in all 7 of patients. We stopped ATM after our patient showed clinical improvement and the ESR and CRP had been normalized (within normal range) for 6 months consecutively (Fig. 2).

The other option we had is, to use antibiotics impregnated cement spacer but with little research has been done with cement impregnated with ATM and only Khater et al.9) has implanted vancomycin and rifampicin loaded beads after prosthesis removal. However, the bioavailability and the toxicity of these antibiotics are questionable. So, until further research is done there is little role of antibiotics impregnated cement spacer in TB periprosthetic infection. From the literature search, nearly all patients with no prior TB infection underwent surgical procedure, ranging from debridement, removal of prosthesis, arthrodesis, resection arthroplasty and revision arthroplasty1,3-5,7-9) (Table 1). The only patient, who did not go for a surgery is a periprosthetic TB infection of TKA which was cured by ATM7).

Hence, from the literature review and this case report, treatment for TB periprosthetic infection has to be individualized according to each case. In this case the TB infection was clinically under control and the prosthesis was stable with insufficient bone stock. We decided to retain the prosthetic implant and use 4 drug ATM with good result for the past 8 years. We presume in this patient reactivation of local skeletal TB as the source of infection because the contralateral THA was not affected.

Figures and Tables

Fig. 1

Anteroposterior view of right hip showing the progress of periprosthetic TB infection. (A) After debridement, (B) one year, (C) two year, (D) three year, (E) five year, (F) seven year follow-up.

References

1. Marmor M, Parnes N, Dekel S. Tuberculosis infection complicating total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004; 19:397–400.

2. Yoon TR, Rowe SM, Santosa SB, Jung ST, Seon JK. Immediate cementless total hip arthroplasty for the treatment of active tuberculosis. J Arthroplasty. 2005; 20:923–926.

3. Baldini N, Toni A, Greggi T, Giunti A. Deep sepsis from Mycobacterium tuberculosis after total hip replacement. Case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988; 107:186–188.

4. Boéri C, Gauias J, Jenny JY. Total hip replacement prosthesis infected by Mycobacterium tuberculous. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2003; 89:163–166.

5. Kreder HJ, Davey JR. Total hip arthroplasty complicated by tuberculous infection. J Arthroplasty. 1996; 11:111–114.

6. Besser MI. Total knee replacement in unsuspected tuberculosis of the joint. Br Med J. 1980; 280:1434.

7. Neogi DS, Ashok K, Yadav CS, Singh S. Delayed periprosthetic tuberculosis after total knee replacement: is conservative treatment possible? Acta Orthop Belg. 2009; 75:136–140.

8. McCullough CJ. Tuberculosis as a late complication of total hip replacement. Acta Orthop Scand. 1977; 48:508–510.

9. Khater FJ, Shamnani IQ, Mehta JB, Moorman JP, Myers JW. Prosthetic joint infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an unusual case report with literature review. South Med J. 2007; 100:66–69.

10. Sidhu AS, Singh AP, Singh AP. Total hip replacement in active advanced tuberculous arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009; 91:1301–1304.

11. Zeiger LS, Watters W, Sherk H. Scintigraphic detection of prosthetic joint and soft tissue sepsis secondary to tuberculosis. Clin Nucl Med. 1984; 9:638–639.

12. Wolfgang GL. Tuberculosis joint infection following total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985; (201):162–166.

13. Levin ML. Miliary tuberculosis masquerading as late infection in total hip replacement. Md Med J. 1985; 34:153–155.

14. Ueng WN, Shih CH, Hseuh S. Pulmonary tuberculosis as a source of infection after total hip arthroplasty. A report of two cases. Int Orthop. 1995; 19:55–59.

15. Tokumoto JI, Follansbee SE, Jacobs RA. Prosthetic joint infection due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: report of three cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1995; 21:134–136.

16. Lusk RH, Wienke EC, Milligan TW, Albus TE. Tuberculous and foreign-body granulomatous reactions involving a total knee prosthesis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995; 38:1325–1327.

17. Spinner RJ, Sexton DJ, Goldner RD, Levin LS. Periprosthetic infections due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in patients with no prior history of tuberculosis. J Arthroplasty. 1996; 11:217–222.

18. Berbari EF, Hanssen AD, Duffy MC, Steckelberg JM, Osmon DR. Prosthetic joint infection due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a case series and review of the literature. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1998; 27:219–227.

19. Kaya M, Nagoya S, Yamashita T, Niiro N, Fujita M. Periprosthetic tuberculous infection of the hip in a patient with no previous history of tuberculosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006; 88:394–395.

20. Shanbhag V, Kotwal R, Gaitonde A, Singhal K. Total hip replacement infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. A case report with review of literature. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007; 73:268–274.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download