Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to develop and evaluate an infection prevention self-care application for cancer patients who have been discharged from hospital after receiving chemotherapy.

Methods

The app was developed through five stages: analysis, design, development, implementation and evaluation. The app's contents included infection prevention education, checking daily self-management, checking daily inquiry and information about the app. Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy were asked to use the app and then a nonequivalent control group non-synchronized design was conducted to analyze the effect of the app on infection prevention self-care knowledge, self-care performance, infection occurrence and temperature. Twenty-two patients in the experimental group and twenty-four patients in the control group participated in this study.

Results

The self-care knowledge score (t=6.74, p<.001) and self-care performance score (t=13.44, p<.001) were statistically higher in the experimental group compared with the control group respectively. The infection occurrence was not different between the experimental and control groups. But temperature in the control group was statistically higher than in the experimental group (t=-2.39, p=.021).

Figures and Tables

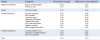

Table 1

Contents of Infection Prevention Self-care Application

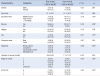

Table 2

Expert Evaluation and User Satisfaction with Infection Prevention Self-care Application

Table 3

Homogeneity Test between Experimental and Control Group (N=46)

Table 4

Comparison the Dependent Variables between Experimental and Control Group (N=46)

References

1. Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016; 48(2):436–450.

2. Chabner BA, Longo DL. Cancer chemotherapy and biotherapy: principles and practice. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2011.

3. Dale DC, McCarter GC, Crawford J, Lyman GH. Myelotoxicity and dose intensity of chemotherapy: reporting practices from randomized clinical trials. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2003; 1(3):440–454.

4. Pettengell R, Bosly A, Szucs TD, Jackisch C, Leonard R, Paridaens R, et al. Multivariate analysis of febrile neutropenia occurrence in patients with non hodgkin lymphoma: data from the INC-EU prospective observational european neutropenia study. Br J Haematol. 2009; 144(5):677–685.

5. The Korean Society of Infectious Diseases. Infectious diseases. 2nd ed. Seoul: Koonja Publisher;2014.

6. Seong CM. Leukemia clinic. 2nd ed. Seoul: Koonja Publisher;2007.

7. Jeong HY, Kwon MS. The effects on self-care knowledge and performance in the individualized education for chemotherapy. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2008; 8(1):8–16.

8. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections Web site. Accessed April 09, 2016. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/infections.pdf.

9. Dorothea O. Nursing: concepts of practice. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw Hill;1985.

10. Kim JY. The effects of infection prevention education on self-care performance and infection occurance in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy [master's thesis]. Daegu: Keimyung Univ.;2011.

11. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman;1997.

12. Krebs P, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS. A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Prev Med. 2010; 51(3-4):214–221.

13. Wang J, Wang Y, Wei C, Yao N, Yuan A, Shan Y, et al. Smartphone interventions for long-term health management of chronic diseases: an integrative review. Telemed J E Health. 2014; 20(6):570–583.

14. Jeon JH, Kim KH. Development of disease knowledge instrument for patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Korean Data Anal Soc. 2015; 17(3):1599–1617.

15. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, Mcfadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982; 5(6):649–655.

16. Lee H. The effect of individualized teaching and telephone counseling on self-care behavior among patients with hematologic cancer [master's thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei Univ.;2000.

17. Shin EY. The relationships among self care knowledge, family support and self care behavior in hemato-oncologic patients [master's thesis]. Kwangju: Chonnam National Univ.;2002.

18. National Cancer Information Center. Cancer patient symptom management Web site. Accessed April 09, 2016. http://www.cancer.go.kr/mbs/cancer/subview.jsp?id=cancer_030207010300.

19. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Prevention of food poisoning Web site. Accessed April 09, 2016. http://www.mfds.go.kr/fm/content/view.do?contentKey=17&menuKey=130.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 Steps Toward Web site. Accessed April 09, 2016. http://www.preventcancerinfections.org/content/discover-3-steps.

21. Lee Y, Kwon I. The relationship between infection prevention behaviors and barriers among cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2007; 7(2):150–161.

22. National Cancer Institute. NCI CTCAE Web site. Accessed April 09, 2016. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf.

24. Oncology Nursing Society. PEP Web site. Accessed April 09, 2016. https://www.ons.org/practice-resources/pep.

25. Doll WJ, Torkzadeh G. The measurement of end-user computing satisfaction. MIS Quarterly. 1988; 12(2):259–274.

26. Bong M. The development and evaluation of a web-based information program for patients undergoing spinal fusion [dissertation]. Seoul: Seoul National Univ.;2005.

27. World Health Organization. Hand hygiene Web site. Accessed April 25, 2016. http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/Hand_Hygiene_Why_How_and_When_Brochure.pdf.

28. Park HA, Kim HJ, Song MS, Song TM, Chung YC. Development of a web-based health information service system for health promotion in the elderly. J Korean Soc Med Inform. 2002; 8(3):37–45.

29. Kang YH. The health promotion internet program for adolescents: a study of its development and effect of adolescents [dissertation]. Busan: Kosin Univ.;2003.

30. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. New Jersey: Prentice Hall;1986.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download