Abstract

Purpose

This study was to examine the factors affecting prostate cancer screening behavior in Korean men using the health belief model (HBM).

Methods

It was a descriptive cross-sectional survey. A total of 121 participants answered questionnaires which included general characteristics, knowledge, and HBM variables related to prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening tests.

Results

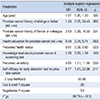

Only 18 participants (14.9%) had had a prostate cancer screening test before. Participants who had had a prostate cancer screening test were more likely to perceive lower health status (odds ratio: 0.61 [95% confidence interval: 0.39, 0.93]), higher perceived sensitivity (odds ratio: 3.55 [95% confidence interval: 1.11, 11.36]), and higher self-efficacy (odds ratio: 5.77 [95% confidence interval: 1.51, 22.08]) than participants who had not had a test.

Figures and Tables

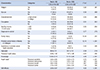

Table 1

Demographics and the Level of Knowledge, Health Belief, and Self-efficacy related to Prostate Cancer and Prostate Cancer Screening Behavior of Participants (N =121)

Table 2

Differences of Characteristics according to the Experience of PSA Test (N =121)

Table 3

Predictors of Prostate Cancer Screening Behavior

References

1. Korea Central Cancer Registry Division. National cancer registry statistics (Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2011). Ministry of Health and Welfare;2013.

2. Jung K, Won Y, Kong H, Oh C, Lee DH, Lee JS. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2011. Cancer Res Treat. 2014; 46(2):109–123.

3. Han JH, Yoon SJ, Lee YG. Background and validity of the promotion of prostate-specific antigen based prostate cancer screening to national cancer screening program. Korean J Urol Oncol. 2010; 8(1):1–9.

4. Song SY, Kim SR, Ahn G, Choi HY. Pathologic characteristics of prostatic adenocarcinomas: a mapping analysis of Korean patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2003; 6(2):143–147.

5. Sirovich BE, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Screening men for prostate and colorectal cancer in the United States: does practice reflect the evidence? JAMA. 2003; 289(11):1414–1420.

6. Melia J, Moss S, Johns L. Rates of prostate-specific antigen testing in general practice in England and Wales in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients: a cross-sectional study. BJU Int. 2004; 94(1):51–56.

7. Collin SM, Martin RM, Metcalfe C, Gunnell D, Albertsen PC, Neal D, et al. Prostate-cancer mortality in the USA and UK in 1975-2004: an ecological study. Lancet Oncol. 2008; 9(5):445–452.

8. Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(13):1320–1328.

9. Park SK, Sakoda LC, Kang D, Chokkalingam AP, Lee E, Shin H, et al. Rising prostate cancer rates in South Korea. Prostate. 2006; 66(12):1285–1291.

10. Rosenstock IM. What research in motivation suggests for public health. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1997; 03. 50:295–302.

11. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons;2008.

12. Redding CA, Rossi JS, Rossi SR, Velicer WF, Proschaska JO. Health behavior models. Int Electron J Health Educ. 2000; 3(Special issue):180–193.

13. The Korean Urological Oncology Society. Clinical guidelines on prostate carcinoma 2004. Accessed December 13, 2012. http://www.kuos.or.kr./05/05.condition.asp.

14. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A, Buchner A. G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007; 39(2):175–191.

15. Radosevich DM, Partin MR, Nugent S, Nelson D, Flood AB, Holtzman J, et al. Measuring patient knowledge of the risks and benefits of prostate cancer screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2004; 54(2):143–152.

16. Boehm S, Coleman-Burns P, Schlenk EA, Funnell MM, Parzuchowski J, Powell IJ. Prostate cancer in African American men: increasing knowledge and self-efficacy. J Community Health Nurs. 1995; 12(3):161–169.

17. Jacobs LA. Health beliefs of first-degree relatives of individuals with colorectal cancer and participation in health maintenance visits: a population-based survey. Cancer Nurs. 2002; 08. 25(4):251–265.

18. Champion VL. Revised susceptibility, benefits, and barriers scale for mammography screening. Res Nurs Health. 1999; 22(4):341–348.

19. Choi KS, Park JK. Epidemiologic Characteristics of Prostate Cancer Detection. Korean J Urol Oncol. 2009; 50(11):1054–1058.

20. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Study report for 5 items of cancer screening test to reach to all population in South Korea. Ministry of Health and Welfare;2004.

21. Park KH. Related Factors to Do Prostate Cancer Screening Test [master's thesis]. Seoul: Chung-Ang Univ;2009.

22. Lee HY, Jung Y. Older Korean American men's prostate cancer screening behavior: the prime role of culture. J Immigr Minor Health. 2013; 15(6):1030–1037.

23. Pierce R, Chadiha LA, Vargas A, Mosley M. Prostate cancer and psychosocial concerns in African American men: literature synthesis and recommendations. Health Soc Work. 2003; 11. 28(4):302–311.

24. Hannover W, Kopke D, Hannich HJ. Perceived barriers to prostate cancer screenings among middle-aged men in north-eastern Germany. Public Health Nurs. 2010; 11-12. 27(6):504–512.

25. Lehto RH, Song L, Stein KF, Coleman-Burns P. Factors influencing prostate cancer screening in African American men. West J Nurs Res. 2010; 10. 32(6):779–793.

26. Kim NS, Lee KE. Effecting factors on cancer preventive behaviors for middle aged man/woman. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2014; 21(1):29–38.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download